Insiders and Outsiders

In the fourteenth century, the illustrious Andalusian rabbi David Abudarham reported a remarkable legal innovation:

I heard in the name of Rabbi Zerahyah Halevi that anyone who does not eat a hot food (hamin) on the Sabbath ought to be investigated for heresy. If he dies, only non-Jews should bury him. . . . But whoever does cook a hot dish and covers it is reckoned among the believers and will merit seeing the End of Days.

Never in Jewish history has so much hung on cholent. Why? The answer lies in Karaism, a Jewish minority sect that rejected rabbinic Judaism by denying its central doctrine: that on Mount Sinai, Moses received an oral Torah that illuminated and expanded upon the written one. Karaites claim that Jews must determine the meaning of the Torah through their own interpretive efforts and are prohibited from relying on the authority of tradition. Because they interpreted the Torah’s ban of fire on the Sabbath to include even those fires kindled before the Sabbath, they had to do without cholent. Meanwhile, rabbinic Jews like Abudarham felt pressure to embrace cholent as an identity marker, not simply as a pleasant Shabbos meal.

Yet even as Jews who accepted rabbinic authority (“Rabbanites”) and Karaites disagreed on theological fundamentals, they identified themselves and their opponents as members of a single religious community. For centuries, Rabbanites and Karaites read and responded to one another’s works, developing their scholarship in tandem. Socially, they often mingled, shared religious ceremonies, depended on one another’s charity, and even intermarried. They saw one another as brethren even as they developed new religious observances and prohibitions to police the boundary that marked the other as outsiders. As Daniel J. Lasker argues in Karaism: An Introduction to the Oldest Surviving Alternative Judaism, the intimacy of the Karaite-Rabbanite encounter has enduringly shaped the ideologies and practices of both groups.

Modern Karaite studies have been hampered by many factors, but the greatest has been that the largest collection of Karaite manuscripts, located in Saint Petersburg, was closed to researchers until the fall of the Soviet Union. Since then, the field has blossomed, but most of the scholarship has been highly specialized, philological, and inaccessible to the general reader. Lasker departs from this trend by providing a lively introduction to Karaism that spans from its origins to the present and persuasively argues for its vital relevance to Jewish studies as a whole

The origins of Karaism are a matter of debate, and Lasker begins by debunking the oft-repeated story that Anan ben David, an eighth-century Jew, founded Karaism when his community snubbed him by choosing his less learned (but more pious) younger brother to succeed their father as exilarch, the political head of Babylonian Jewry. The story goes that a disgruntled Anan proclaimed himself exilarch nonetheless. Since the office was ultimately appointed by the caliph, Anan’s actions were deemed an affront to the ruler, and he was thrown in jail. There he met a Muslim scholar who suggested he create his own religion and gave him some pointers on how to differentiate it from Judaism. Because each religion was entitled to its own leadership, he reasoned, Anan would be able to serve as a religious leader without directly challenging the authority of either the Jews or the caliph. The Muslim scholar’s plan worked, and Karaism began.

Like most scholars, Lasker dismisses this as a just-so story that blatantly echoes the classic themes of anti-Karaite polemics: that Karaite doctrine was self-serving and aimed at Islamicizing Judaism. Moreover, contrary to the story’s claims, Anan’s sect appears to have originally been distinct from the Karaites. Lasker, however, does not deny Islamic influence on Karaism, and he provides examples in the areas of law and ritual.He might have added that a frequent Islamic charge against Jews was that the rabbinic tradition had led them to interpret away, and hence abandon, much of God’s original revelation to Moses. Karaite Judaism was more immune to such charges because of its scripturalism and rejection of rabbinic authority.

Karaite accounts of their own origins vary, but they tend to see their religion as dating back to biblical times and rabbinic developments as a later heresy. As Lasker notes, even if one does not accept such claims, understanding the Karaites as an umbrella group for nonrabbinic Jewish sects dating back to antiquity is a useful way to explain the movement’s initially broad appeal and growth. It was only at the end of the ninth century, however, that some sectarians began to call themselves Karaites, a term likely deriving from the word mikra (scripture). “Search scripture well and do not rely upon my opinion,” a slogan often attributed to Anan, became their guiding principle.

For this reason, unlike rabbinic Jews, Karaites made the study of Hebrew a universal and binding religious obligation. The directive to interpret scripture inspired Karaites to write the first medieval Jewish Bible commentaries. Many of these were known for their grammatical rigor and source-critical approach. In a move paralleling that of modern biblical critics nearly a millennium later, Karaite exegetes introduced a figure known as the mudawwin, or author-redactor, whom they believed was responsible for the organization of biblical literary units. Some Karaites claimed Moses as the mudawwin, while

others cautiously left room for different answers.

The Karaite emphasis on individual freedom of interpretation soon became a communal liability. As one tenth-century Karaite despairingly wrote of the community’s growing fragmentation: “No two Karaites agree on anything.” In response, there developed a begrudging acknowledgment that some communally accepted norms were needed to standardize ritual and create unity. Karaite jurists refer to these standards as “the burden of inheritance” (sevel ha-yerushah).

Lasker shows that, for most of premodern Jewish history, Karaites regarded themselves, and were regarded by others, as part of the Jewish community. He adeptly shows how this played out in works of theology and biblical commentary. He also notes that Karaite-Rabbanite intermarriage often occurred despite frequent concerns. Frustratingly, however, Lasker gives his readers almost no taste of the social history of such intimate relations even though scholars such as Shelomo Dov Goitein, Moshe Gil, Marina Rustow, and many others have spent decades illuminating the fascinating world of Karaite-Rabbanite joint ventures, from legal courts and political advocacy to public prayer and charity.

It is very difficult to provide even a rough estimate of the size of Karaite populations. Lasker cautiously suggests that, in the medieval period, Karaite populations in the Islamic world “must have been significant, although never close to a majority.” By contrast, in Europe, Karaites represented “just a tiny fraction of the Jewish population, probably never more than a few thousand individuals.” The exception was Crimea, where Karaites did significantly outnumber rabbinic Jews. Lasker estimates that, today, the world Karaite population is, at most, fifty thousand strong, the majority of whom live in Israel.

Unsurprisingly, Karaite-Rabbanite relations were not always harmonious. To cite an extreme example, a youthful Maimonides ruled that a rabbinic court could execute Karaites as heretics. Once he became a community leader, however, Maimonides ruled that it was permissible to visit sick Karaites, circumcise their children, and even drink their wine. Yet even when Karaites were not discriminated against, as a minority, they felt immense social pressure to conform to majority practices, particularly with regard to their Sabbath observance. Karaites have traditionally banned all fires on the Sabbath, spending the day of rest in darkness and, in Europe, often in great cold. Yet, over time, Karaites softened their views. They originally were prohibited from lighting Sabbath candles, but such was the cultural power of the rabbinic practice that, beginning in the fifteenth century, many Karaites also began to light them. Rabbinic ideas also seeped into Karaite consciousness. According to one major Karaite legal authority, Maimonides’s works were even to be regarded as a valid source of law.

The Karaites of the Middle East continued to identify themselves and be identified by rabbinic Jews as members of the Jewish community. Initially this was also the case in Eastern Europe, where Karaites had lived since at least the thirteenth century. Until the end of the seventeenth century, Karaites were fairly integrated within the Jewish community, despite speaking their own Turkic dialect, “Karaim.” While rabbinic knowledge of Karaism was usually minimal, educated Karaites were at home in the world of Rabbanite texts. Karaites paid their taxes through the Council of the Four Lands (the central institution of Jewish self-government in Poland) and suffered together with Rabbanite Jews during the Khmelnitsky massacres.

In modern Europe, however, pressures from the non-Jewish world eventually led most European Karaites to cease to regard themselves as part of the broader Jewish community. In the eighteenth century, as a result of a series of anti-Jewish regulations, Karaites began to claim to Christian authorities that they were different from their Rabbanite brethren. The Talmud had been the object of vociferous Christian attack and, to escape persecution, Karaite leaders indicated that they too opposed the Talmud. They further argued that it had been the proto-rabbinic Pharisees and not the Karaites who had been responsible for Jesus’s crucifixion. On such grounds, in 1774, the Habsburg empress, Maria Theresa, reduced their taxes and welcomed them as “exemplary Jews” who could set a good example for their wayward Rabbanite brethren.

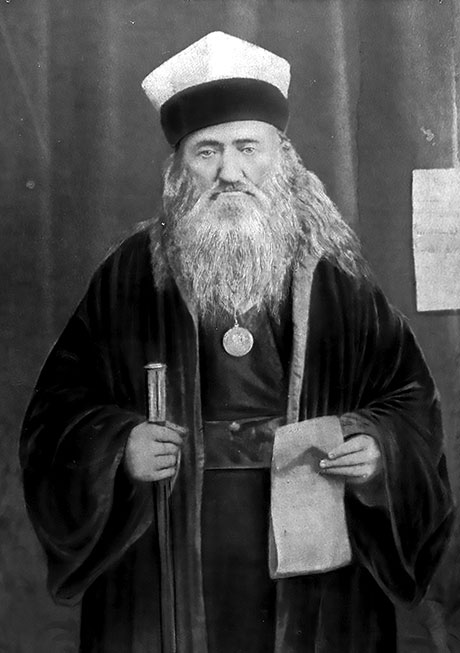

When Russia drafted Jewish youths into the army with the goal of separating them from their families and subjecting them to missionary pressure, the Karaites received an exemption from Tsar Nicholas I. The European separation between Rabbanites and Karaites was finalized by the Karaite leader Seraya Shapshal. Shapshal argued that Karaites were not of Semitic origin like other Jews but were of European Khazar stock. With a playbook echoing Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s reforms in Turkey, he changed the script of the Karaim language, excised its Hebrew vocabulary, and abolished the study of Hebrew, which had been a cornerstone of Karaism. He also acknowledged both Jesus and Muhammad as prophets, added elements of pagan folk religion, and removed images of the Star of David and Ten Commandments from Karaite synagogues. As a result of Shapshal’s efforts, the Nazis exempted most Karaites from persecution on the grounds that they were not racially Jewish. Although some Karaites were nonetheless murdered during the Holocaust, others survived by collaborating with the Nazis or joining the Red Army. As for Shapshal, he spent the war in Vilna, undisturbed either by the Nazis or by the Soviets when they conquered the city.

The Karaites of the Middle East mostly resided in Egypt until 1967. Although initially encouraged by their leadership to remain there after the founding of the State of Israel, this changed with the failed Israeli covert operation, known as the “Lavon affair,” which resulted in two Egyptian Jews being hanged as Israeli agents, one of whom was a Karaite. After the Suez War, Middle Eastern Karaites quickly migrated, settling in Israel, California, and Switzerland.

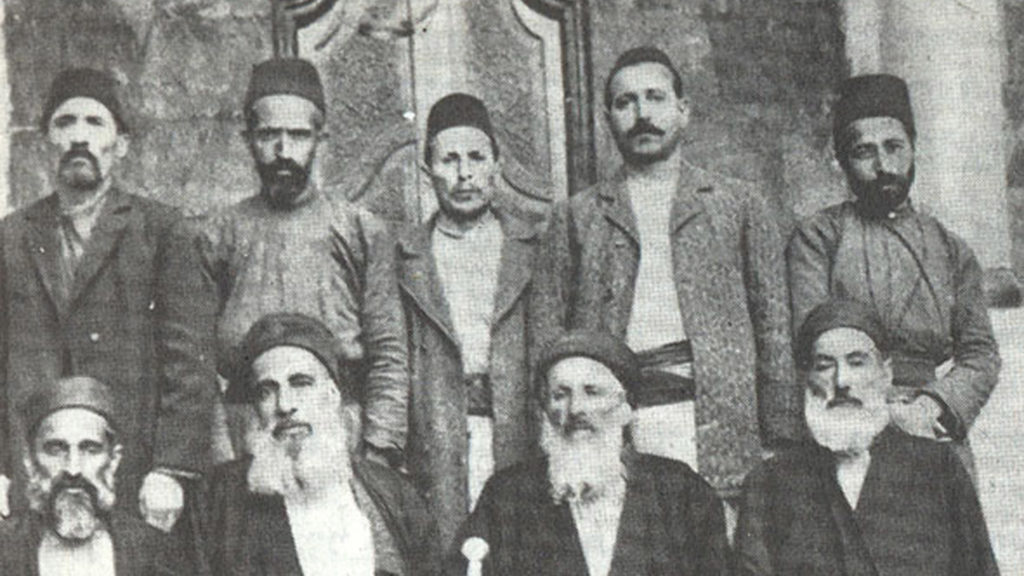

Some of the most engaging moments in Lasker’s book are his intellectual portraits of Karaite thinkers. For instance, Simhah Isaac Lutski was an eighteenth-century Eastern European Karaite who wrote a Karaite theology that blended medieval Aristotelianism with Lurianic Kabbalah. Abraham Firkovich was a nineteenth-century eccentric Karaite leader who traveled the Middle East and amassed the largest collection of Karaite manuscripts (some reportedly given to him in exchange for his promises to send the former owners Russian Karaite brides). Firkovich so perfectly spoke the language of Wissenschaft des Judentums that many maskilim, already sympathetic to Karaism’s skepticism of rabbinic claims, were taken in by his many forgeries designed to prove Karaite antiquity.

Karaism is an academic work, but Lasker’s personal affection for the Karaite community shines through. He relishes the achievements of the Karaites, their Bible commentaries, their innovative halakhic works, and their medieval calls for more Jews to settle in the Land of Israel. He has even served as the thesis adviser of the Karaite chief hakham of Israel.

He also sympathizes with the struggles of contemporary Karaites to practice Judaism, particularly as a tiny minority in Israel. In the early years of the state, Karaites were serviced by the section of the Ministry of Religious Affairs that dealt with Muslims and Druze. After they protested, they were included in the section that dealt with Samaritans and Indian Jews, with whom they have little in common. Their status as Jews has not been resolved by the Israeli Rabbinate, which has created considerable difficulties for Karaite-Rabbanite marriages. Unlike other Jews in Israel, Karaites struggle to get time off for their Jewish holidays, which are usually held on different dates, and receive little support for their educational institutions. Yet Lasker is impressed by their resilience.

Whither the Karaites, asks Lasker? A new golden age is unlikely, he answers, but don’t count out the Karaites yet.

Suggested Reading

Secularism and Sabbateans

How did the Jews become modern? Three new books trace the roots of Jewish secularization.

That in Aleppo Once

Does the most accurate biblical text belong in the synagogue, or in a museum?

The Exilarch’s Lost Princess

In real life, or as much of it as historians can reconstruct, Septimania was a name for the region of southern France that included the Jewish populations of such venerable cities as Carcassonne, Narbonne, and Toulouse. Jonathan Levi leans on the most delightfully far-fetched version of these events in his latest novel.

Exit, Loyalty … Crowdsource?

It is a bit of a surprise to open a big-think policy book on the fate of the Jewish people and read a Jason Bourne scene with a prep-school payoff, but Tal Keinan is entitled to it.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In