Problems with Authority

A lot happens in Paul Goldberg’s new novel The Dissident, set in 1970s Moscow. A couple falls in love and gets married. A groundbreaking human rights organization is founded. Several people get axe-murdered.

All of these events are relayed with a confidence that at first is very appealing. Charismatic, confident, and authoritative, the omniscient narrator assures us, “Here are the facts, dry, bare, like skeletons of rats.” The narrator’s frequent assertions, asides, and explanations reinforce this impression of the novel’s reliability:

Dates matter. November 28 is the first night of the Jewish holiday of Chanukah. January 13 is the Old New Year, what New Year’s Eve used to be before the Bolsheviks switched from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian.

Copious footnotes offer explanations of historical events and translations of Russian phrases; for example, the comment “ваше дело молодое, а наше дело старое” in the body of the novel is roughly rendered as, “Young people have their agendas while old people have theirs.” The footnotes and other narrative incursions are not playful metafictional devices meant to underscore the artificiality of the fictional form. Rather, and despite some ironizing (“Footnotes are denigrated as pedantic, Talmudic, German even”), the footnotes function as they might in a scholarly paper from the nineteenth century: to add details, clarify ambiguities, and generally bolster the narrator’s account.

So while The Dissident is at times a charming and lyrical work, capable of transporting readers into a Moscow winter or into the giddiness of falling in love, its intentions point in a different and more didactic direction. In his acknowledgements, Goldberg places The Dissident in the tradition of Russian novels such as Pushkin’s Eugene Onegin, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, andVasily Grossman’s Life and Fate: “You need Onegin to understand the Decembrists. For the Battle of Borodino you need War and Peace. . . . You need Life and Fate to understand the Battle of Stalingrad.” The implication is that perhaps future readers might come to The Dissident to understand the Soviet dissident movement, but that would be unfortunate.

Viktor Moroz and Oksana Moskvina are two dissidents in love. He is a refusenik and occasional translator and uncredited coreporter for English-speaking journalists; she is an idealistic teacher who sometimes contributes to the production of samizdat, the underground publication of banned texts. We find them on their wedding night, waiting for the arrival of a friend who will help add Jewish ritual to the wedding:

One of the guests—Albert Schwartz—has promised to bring along three old men who remember how weddings were performed in their shtetlekh. A Jewish wedding—a khasene in shtetl—creates its own context, even here, even in Moscow, even today, on January 13, 1976. The old men—alterkakers is the Yiddish word, “old shitters”—will take the ritual through the paces, mumble the right blessings in Hebrew, sing something in Yiddish when it’s over.

This newly married couple, along with assorted dissidents—“an artist known for sculpting war amputees . . . a Pushkinist who, owing to a childhood bout of tuberculosis, is as pale and gaunt as a politzek . . . an erstwhile paratrooper”—are presented with the mystery of the violent double murder of Albert Schwartz and his lover. The passive voice seems fitting here, because no one does anything much about the murder for most of the novel. After discovering the bodies, Viktor spends hundreds of pages deciding whether to try to figure out who did it. Conversations on this topic are desultory and, despite the axes, rather bloodless.

Although I was never compelled by the murder mystery, a different question kept recurring to me as I encountered several questionable narrative assertions about history:Is this novel really saying what I think it’s saying, and if so, why? A historical novel need not be correct in all its details, nor do its characters’ fates need to reflect some sort of average—a novel is not an information delivery vehicle—but if it makes claims to accuracy, readers need to be able to trust its larger assertions.

The Dissident takes place in the politically charged year of 1976, during the formation of the revolutionary human rights organization, the Moscow Helsinki Group. Alongside and intersecting with such entities was the Jewish emigration movement, which included refuseniks like Viktor. These two movements overlapped but had distinctly different goals. To oversimplify, entities like the Moscow Helsinki Group tried to make the Soviet Union a freer and more democratic place, while the refuseniks sought freedom outside its borders. Differences also existed within the groups—for example, between secular and religiously seeking refusenik Jews. Meanwhile, the Soviet government targeted all dissidents alike, imprisoning publishers of samizdat, cracking down on any attempted protests, and orchestrating show trials to demonstrate the futility of seeking greater freedom either within or without the USSR.

At this tense historical moment, Viktor finds himself under threat of being framed by the state for the murders if he doesn’t become a secret government collaborator. Desperate for guidance, trying to decide on the lesser of two evils, and wondering if he can survive a trumped-up trial, Viktor asks his friend Vitaly Golden for “a historian’s perspective on anti-Semitic trials.”

Vitaly responds, with surprising jauntiness, that “the outcomes aren’t too bad.” After all, he says, Dreyfus was eventually reinstated, and Beilis was eventually exonerated (after years of prison torture—not mentioned here); as for the infamous Stalin-era Doctors’ Plot, in which nine prominent Jewish physicians were falsely accused, imprisoned, and slated for execution, he continues:

They were arrested, yes, but most of them were released from prisons and delivered to their apartments by the same people who arrested them. In a matter of months—an excellent outcome, except for the two or so who died during interrogation. It was a close call, but nearly all of them ended up in the “survived” column.

Putting aside the elision of deaths under torture, what are we to make of the proposition that the Doctors’ Plot persecutions were . . . not so bad? Here is Goldberg’s own description of the returns from arrest of two falsely accused doctors in an earlier, nonfiction account of the dissident movement, The Thaw Generation, cowritten with the former dissident Lyudmila Alexeyeva:

One night in April 1953, Eliazar Markovich and Ginda Khaimovna Gelshtein were brought home by the same people who had arrested them. Ginda Khaimova looked like half of her former self. . . . She had the look of a middle-aged person who had suddenly and irreversibly grown old. But her eyes were the same, and that was a sign that not all was lost. . . . “Such cruelty, such mistreatment!” she said. . . . Eliazar Markovich was now an invalid.

As Vitaly says in the novel, the Gelshteins were indeed returned home—but this was thanks only to the extraordinary coincidence of the death of Stalin, a fact that goes unmentioned here. “An excellent outcome” is not the phrase that comes to mind.

One might think that Vitaly’s comments are some kind of joke, an extended ironic bit, but Viktor seems to take the historian’s lecture as straightforward instruction, responding only with a faithful précis: “So, to summarize, over the past eight decades, defendants in anti-Semitic trials have done reasonably well—worldwide?”

Viktor then acts on Vitaly’s instruction, deciding to risk being prosecuted in an antisemitic show trial. After all, he reflects, not only is this option good for his self-esteem, but it also provides, “hands down,” a much better chance of survival than does collaboration. And at the end, events seem to confirm these perspectives: Viktor emerges from the Gulag unbroken, into an intact family and a fairy-tale future that even includes an American-raised child who speaks perfect Russian.

This is not the outcome one would predict from reading, say, the archives of the Chronicle of Current Events, a samizdat publication of the time with which the characters in this novel are familiar. Moreover, risks fell not only on the dissidents themselves but also on their family members. (Viktor’s own father is a two-dimensional Soviet stooge, which, conveniently, frees Viktor from taking his fate into consideration; Oksana seems game for anything, with a larkish attitude not very typical of women in the dissident movement.)

In his Acknowledgments, Goldberg asserts that, “In Russia, at least, distinguishing fact from literature is a fool’s errand.” And yet, this novel is itself a powerful argument for attempting that errand; otherwise, we are in danger of mistaking narrative opinion for settled truth. And in so doing, we may fail to understand not only history itself but also the ways in which it has impacted the lives of the people we encounter.

Why does Goldberg’s novel depart from history, and why in these ways? The denouement of its murder mystery sheds some light. Shortly before the book’s conclusion, we meet a couple of unpleasant Jewish dissidents, a sort of reverse-mirror image of Viktor and Oksana. Vladimir Lensky (who shares a name with the Eugene Onegin character, as readers are often reminded)and his wife, Olga Lenskaya, are religiously observant and rule bound, petty minded and prejudiced. They’re rude to Oksana, and they don’t get Bulgakov’s classic novel The Master and Margarita. They also turn out to be axe murderers.

When Lensky is found out, we learn that he was under orders from the Mossad to prevent Jewish involvement in human rights groups: “No more Jewish blood on goyish altars.” In contrast, all those characters who are broadly tolerant of religions and sexualities (in a way that is hard to believe even of most dissidents of that era) and focused on universal human rights turn out to be entirely innocent.

This tendency to draw moral distinctions between characters based on their ideologies goes some way toward explaining what otherwise seems like a mysterious novelistic vendetta against the so-called Leningrad group, real-life Jewish dissidents with little connection to the novel’s events. Members of the group focused their protests on a distinctly Jewish goal, that of making aliyah, rather than on the broader goal of human rights, and perhaps this is part of the reason why the novel keeps hauling them in for tongue-lashings:

A group of refuseniks in Leningrad attempted to hijack an airplane and fly it to Sweden. Originally, the plan was to gather two hundred escapees, but in the end, only sixteen were brave enough to show up at the airfield. No greater gift could have been made to the KGB: clear evidence that the Jewish movement was not peaceful after all. . . . How were these crazy Jews different from the Arab terrorists of Black September? Was this a provocation by the KGB or the Leningrad Communist Party? Or was this genuine idiocy on the part of Jewish hijackers? Inexplicably, the West came to regard these people as heroes.

In actuality, and unmentioned in this novel, two of the group’s leaders received death penalties, reversed only after an unexpectedly intense international outcry. The show trial and resulting outcry also helped bring about a temporary relaxation in Soviet immigration restrictions, allowing many more Jews to leave the USSR. This was exactly what the group’s members, in their “idiocy,” had hoped to accomplish.

In Vitaly’s historical roundup, in Viktor’s happy ending, in discussions of Jewish groups and observant Jews, this novel seems to be saying something like this: antisemitic persecutions usually don’t go too badly for us Jews, so instead of being narrowly, even selfishly, focused on our own safety and freedom, we should widen our gaze and devote our energies to more universal matters.

Marketing materials present The Dissident as a Jewish novel, mislabeling its religiously and politically diverse characters “a ragtag group of Jewish refuseniks.” To the extent that The Dissident is, in fact, a Jewish novel, it is because it engages in the very old Jewish debate about assimilation (or progress, or humanism) versus tradition (or self-determination, or chosenness). Do we try to make things better in the place where we find ourselves, or do we attempt an escape to Jerusalem? The Dissident might have engaged interestingly with these questions—as does Grossman’s Life and Fate, a more successful, also partially Jewish, novel. However, Paul Goldberg’s novel is limited by its over-determination and Manichaean simplicity.

It was not Eugene Onegin or Life and Fate or any of the other books alluded to in The Dissident that came to mind as I read it. Rather, despite their differences in ideology and the far-superior literary powers of Goldberg, I was reminded of Ayn Rand (who, as it happens, was also born a Jew in Russia). The Dissident is in a way a Randian concoction: an antiauthoritarian novel in which the narrator is the ultimate authority. When characters echo the narrator’s opinions, and events in the novel further confirm their rightness, there is no room left for thought. The author decided the questions on our behalf long before we began to read.

The Dissident also differs from novels like Life and Fate in another way: it picks and chooses among the characters it deems worthy of understanding (or not).Like its own religious-Zionist villains, this novel is uninterested in identifying points of shared humanity with those of differing beliefs. Explicitly so: a chapter supposedly from the point of view of Vladimir Lensky begins with the assertion that “no effort will be made to explore the storms that rage within the soul of the man” because the heroine Oksana “is our primary concern.” This feels inadequate, as does the chapter’s depiction of Lensky’s thoughts, which are all cardboard doctrine (the murdered men are referred to as “sodomites”) and robotic action (“orders have been received”). This novel proclaims humanistic values but relentlessly dehumanizes its negative characters.

Goldberg writes, “Historical fiction can explore territories where historians cannot go.” Where does he think those territories might be, I wonder? Fiction can take us into those places that don’t make sense unless they’re seen from the inside: the souls of people different from ourselves, people we might even find repellent. Vasily Grossman opened for readers as best as he could the hearts of party “activists” stealing food from Ukrainian children. Unfortunately, in this novel, the desire to be an authority seems to have overtaken the authorial impulse to empathize.

Suggested Reading

Patriotism and Its Discontents

While many Jews embraced the Russian revolutionary cause from the very beginning—four of the seven members of the first Bolshevik Politburo were Jews—the revolution did not embrace them for long.

Sharansky’s Exodus

Witnessing the modern exodus of Jews from Ethiopia to Israel—different than his own but no less stirring—reminded Sharansky of what he’d told himself in his darkest days in prison: “Your history did not begin with your birth or with the birth of the Soviet regime. You are continuing an exodus that began in Egypt. History is with you.”

Spiritual Survival

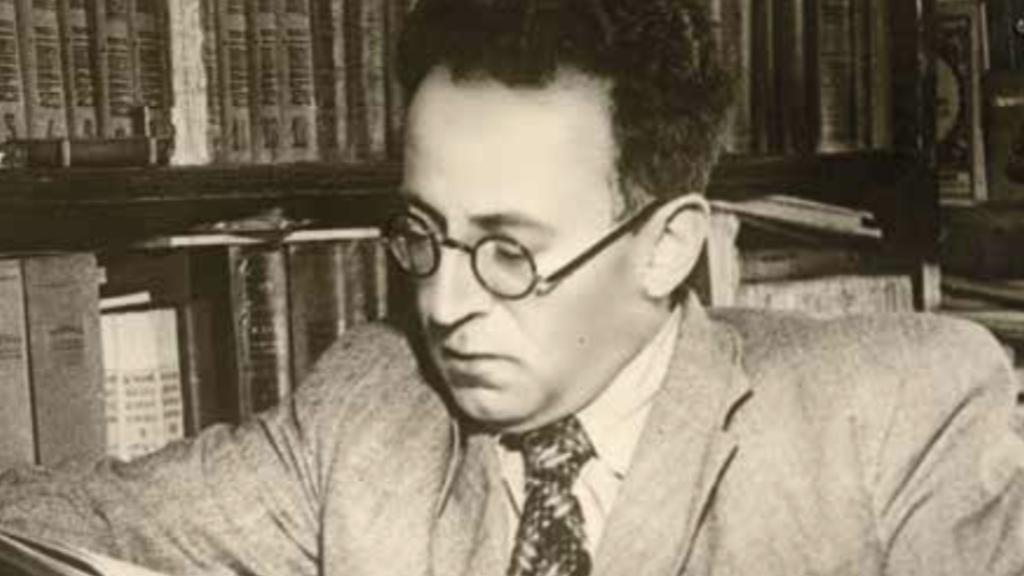

In 1960, the novelist Vasily Grossman wrote to then-premier Nikita Khrushchev with an unusual intention. He wished, he wrote, to “candidly share my thoughts” with the most powerful man in a country that often murdered bearers of candor.

Max, Moritz, and Marx

When the Soviet official asked me about the second book I was carrying, I said rather nonchalantly that this was my Hebrew translation of Karl Marx’s Early Writings, which I was going to give to my hosts.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In