Swimming through History

The first time Alfred Nakache died, it was in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. The second time, it was in the water, where he was most at home.

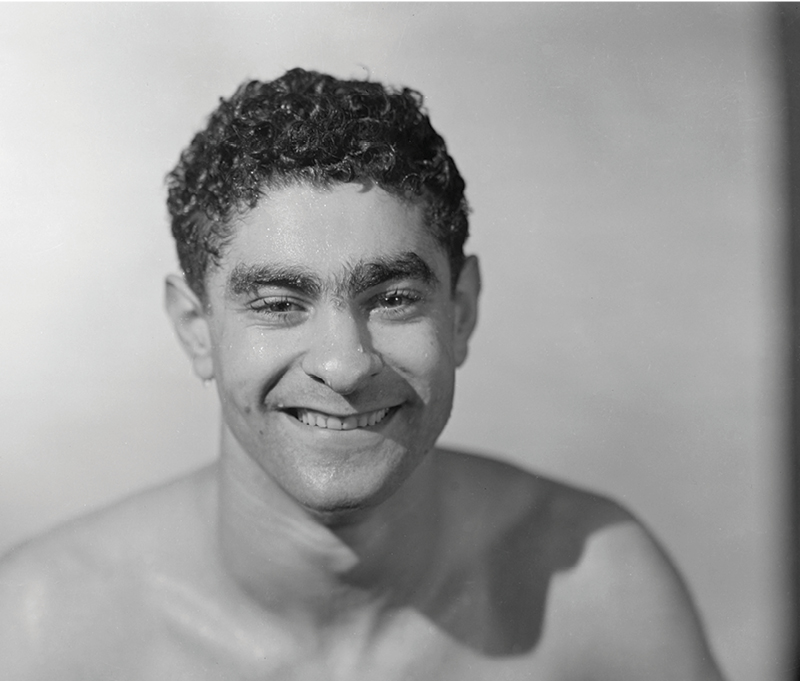

Nakache had an eccentric swimming style, ungainly by contemporary standards. The water roiled around him. His pace lagged far behind the intergalactic speeds of contemporary Olympians—he would easily be lapped by Michael Phelps, Katie Ledecky, or Léon Marchand, who recently broke Phelps’s last standing world record and is the favorite to take home gold in the Olympics this summer. But in the 1930s and 1940s, Nakache devastated the competition. The French press referred to him lovingly by his nickname, “Artem.”

Nakache was famous for his determination, his power, and, above all, his water feel, that ineffable intimacy that swimmers prize. This was before the collaborationist Vichy France regime and the genocidal Third Reich murdered Nakache for the first time.

Nakache was born in Constantine, Algeria, in 1915, one of ten children in a traditional Jewish family. According to the Crémieux Decree of 1870, the Nakache children—like most Jewish subjects in colonial Algeria but unlike their Muslim neighbors—were granted French citizenship upon birth. We don’t know what inspired Nakache’s parents to give the boy swimming lessons—even in Constantine, whose Aïn Sidimecid pool was one of the oldest pools in North Africa, this was rare. Nakache trained alongside Muslim, Christian, and Jewish boys. By the time he was sixteen, he had won gold at the North African Championships in the 100-meter freestyle.

Constantine was a city of athletes. Large numbers of European settlers had moved to the Algerian city at the turn of the twentieth century, bringing with them the boxing ring, the swimming pool, and a violent streak of antisemitism. In the late summer of 1934, the city witnessed the most intense anti-Jewish violence known to the region. Right-wing European Christian settlers consciously inflamed tensions between local Muslims and Jews in an effort to thwart political reforms in French colonial Algeria. The ensuing riot left twenty-five Jews and three Muslims dead. But by then Nakache was swimming with the Racing Club of Paris.

He placed second in the 100-meter freestyle at the 1934 French Nationals. Between 1935 and 1938, he earned seven French national titles, and between 1941 and 1942, six more. During this period, Nakache represented France and Morocco at the Second Maccabiah Games in Tel Aviv in 1935 in the 100-meter freestyle and water polo, respectively.

At the notorious 1936 Summer Olympics, in swastika-draped Berlin, Nakache helped France take fourth in the 4×200 meter relay. Most German Jewish (and other “non-Aryan”) athletes were barred from competition, but several Jewish and Black athletes from other countries—most famously, Jesse Owens—proudly defied Nazi racial theories under the angry gaze of the führer. A show of force in 1936 Berlin felt like a political triumph to athletes deemed “subhuman” by the Nazis, and Nakache’s later remarks suggest that he was among them. For others, like the Austrian Jewish swimmer Ruth Langer Lawrence, who boycotted the Berlin Games, participation legitimized a dangerous regime. Athletically speaking, Berlin was a stepping stone for Nakache. In the years that followed, he won the freestyle on the French national stage a staggering six times and the breaststroke four times. In July 1941, he set a world record (the first by a French swimmer) in a long seawater course in Marseilles. The record stood for five years.

But this is a timeline as viewed from the water. Nakache’s stunning success as a competitive swimmer ran parallel to the rise of Nazism in Europe, the unfurling of antisemitic and racist legislation, and in time, genocidal policy across the continent.

With war in the air, Nakache interrupted his training in 1939 to join the Free French Army, serving for ten months alongside his two brothers in Algeria. In July 1940, he returned to an occupied Paris. A month earlier, the aging First World War hero and newly acting prime minister Henri Philippe Pétain signed the infamous armistice agreement with Germany. The agreement established German occupation over northern and western France and placed southern France under a new collaborationist regime headquartered in Vichy. The Vichy government immediately implemented racist and antisemitic laws that mimicked (and in some cases exceeded) those in Nazi Germany and its occupied territories. It also established concentration, internment, prison, and forced labor camps in France and in territories under its control, including in North Africa.

Nakache and his wife, Paule, who was also an Algerian Jewish competitive swimmer, fled Paris in December 1940, after most Jews had already left. Presumably, up until then, the couple were protected by Alfred’s fame. Even in flight, the Nakaches were able to choose their destination, which was Toulouse. Nakache was welcomed by its swimming club, the Dauphins du Toulouse Olympique Employés Club (TOEC), and even assumed a new teaching position. That Nakache was Jewish was not much of a mystery—he had competed in the Maccabiah Games only five years earlier, and his was a relatively common Algerian Jewish surname. Meanwhile, Nakache helped the Resistance in Toulouse, joining in the training of new recruits and in distributing anti-Nazi literature. The swimmer was hiding in the open air, sheltered by his own fame and a few protectors.

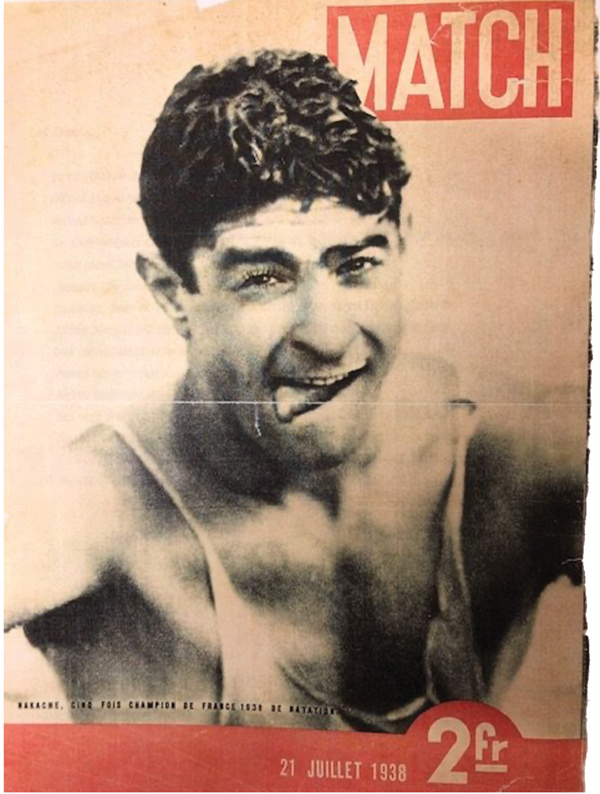

And so Nakache continued to train, compete, and win medals in the early years of World War II, his exploits covered regularly in the press. The antisemitic Le Pilori called him “a super-natural man, this half-god with frizzy hair and wide nostrils . . . the Jew Artem Nakache, member of the Zionist association Maccabih, laureate of Jewish Olympics [sic].” The sports magazines Match and the antisemitic Revivre, le grand magazine illustré de la race published the same cover photo of Nakache emerging from the pool with his tongue lolling animalistically, as if confirming Nazi racial theories. Finally, in early winter of 1942, under the urging of the general governor of Algeria, the Vichy Commissariat responsible for defining Jewish status and implementing antisemitic policies demanded Nakache complete the census required of all Jews.

The most extended account of Nakache’s life, a melodramatic French biography, centers the Olympian’s life story on his rivalry with and ultimate betrayal by French breaststroke champion Jacques Cartonnet. Cartonnet was a virulent antisemite and a zealous member of the French fascist militia, the Milice française, and he was believed by Nakache and others to have reported Nakache to the authorities. But even without Cartonnet’s alleged betrayal, Nakache’s informal athletic immunity couldn’t have lasted.

In the summer of 1942, the French police detained and interned more than twenty-eight thousand Jewish men, women, and children, holding them in the Vélodrome d’Hiver, Paris’s most famous indoor stadium. From there the arrested were taken to the Drancy internment camp on the outskirts of Paris and then deported to Auschwitz. Newspapers across France demanded to know whether the country’s greatest swimmer was Jewish, even as he was scheduled to participate in a propagandistic sports tour of North Africa sponsored by the Vichy regime. That fall, Nakache climbed the winner’s podium under the watch of the French military commander in Tunisia, General Barré, and Prince Muhammed Raouf Bey, son of the Bey of Tunis, Tunisia’s dynastic head of state.

In August 1943, the French Swimming Federation barred Nakache from competition. Teammates from the TOEC and a Tunisian team known as ROT forfeited a meet in Toulouse in protest, and fans demonstrated against Nakache’s absence. Such public solidarity with a Jewish victim was rare in Europe.

With a tip from the Milice française—whether it was ultimately from Cartonnet or someone else—the Gestapo arrested Alfred Nakache, Paule, and their toddler, Annie (who they had taken back after temporarily hiding her with friends and in a convent). The family was held in a Toulouse prison before being transferred to Drancy. From there, the Nakaches were deported to Auschwitz on convoy 66 in January 1944.

Technically, Alfred, Paule, and Annie Nakache were not deported because they were Jews but because they were “foreign” Jews. This was true in Vichy France, although as Algerian Jews, Alfred and Paule had both been granted French citizenship at birth, and Annie had been born in France. Nakache was also charged with aiding the Resistance. After the war, he explained that he had been charged with “anti-German propaganda because I continued to beat the records of German swimmers.”

Paule and Annie were gassed in Auschwitz within two weeks of their arrival; Alfred was consigned to forced labor. He was also forced to entertain the Nazi overseers by diving for daggers thrown by guards into the camp’s water tank.

In the chaos after the war, the French press declared that Nakache had died at Auschwitz. Some headlines blamed “German Torturers,” others “the Milice,” while a supposed eyewitness offered ludicrous testimony that he had seen Nakache’s grave, as if individual graves were a feature of the camps. Nakache’s erstwhile pool in Toulouse, the training place of the TOEC, was even renamed in his memory. In fact, as Soviet forces approached Auschwitz in 1945, Nakache had been among those inmates sent on the death march to Buchenwald, but he had survived.

In Buchenwald, Nakache met journalist Roger Foucher-Créteau, the brother of a swimmer he knew from Toulouse. With Foucher-Créteau’s help, he put pen to paper for the first time in fifteen months. Nakache wrote of how horribly alone he had felt in Auschwitz, where even “our ‘racial brothers’ martyred us due to our ignorance of Yiddish.” In a hurried pen in a simple notebook, Nakache wrote mournfully of the victims, of his accused betrayer Jacques Cartonnet, and of the “unstoppable vengeance” that was due the Nazis, whom he called “the barbarians.” When he wrote these lines, Nakache did not yet know that his wife and daughter had been murdered. “We still have hard times to go through,” he concluded, “but, resolute, we look to the new path that humanity will chart for itself.”

Nakache concluded the document in Arabic with a smaller French translation by its side: “everything has been written [Maktub] and we make it through by the will of God [Allah].” A recent account of Nakache’s life naively dismisses this as proof of his sense of humor. But there was something fundamental in this Arabic finale and in Nakache’s angry reference to the Yiddish-speaking fellow prisoners who he felt had persecuted him. Nakache experienced arrest, internment, deportation, slave labor, Auschwitz, and a death march not only as a Jew but as a North African. When he was finally liberated, Nakache weighed eighty-eight pounds.

In June 1945, Nakache confided to the magazine Ce soir that “I am readapting bit by bit and I plan to settle down in Toulouse. I might go back to the gym that I directed before my deportation. Physically, I am back on top, but my spirits are still low.” Astonishingly, less than a year later, he was competing again. In 1946, he helped set the 3×100 meter relay world record.

In 1948 Nakache swam for the French team, the first Holocaust survivor to earn a place on an Olympic team and one of only two to ever do so. In the London Summer Games, Nakache reached the semifinals in the 200-meter breaststroke and played on France’s water polo team, which placed sixth. (In 1956, Ben Helfgott, a Jewish weight lifter from Poland and a survivor of Buchenwald and Theresienstadt, competed for Great Britain.)

After the war, the French Swimming Federation declared that politics and sports should never again mix. This rushed effort to move beyond the organization’s dark wartime history was part of President Charles de Gaulle’s grand project of reinventing France’s complex wartime history as a simpler tale of victimhood and resistance.

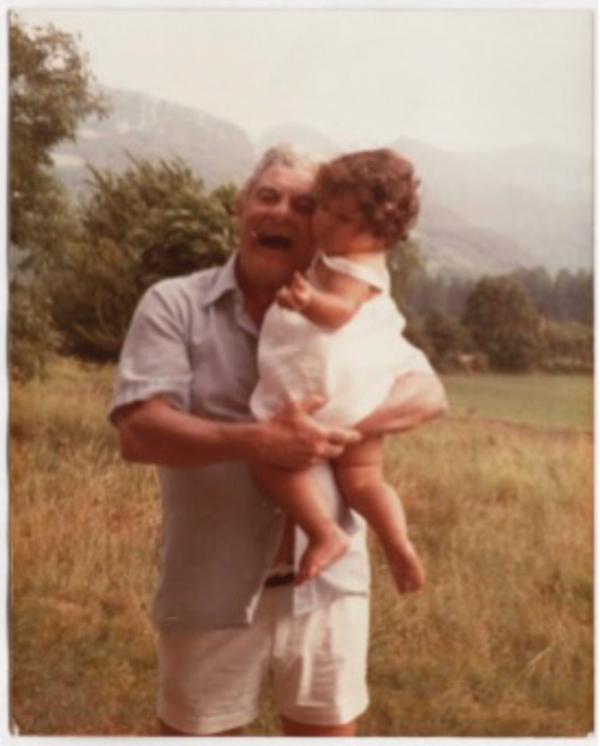

Nakache himself returned to southern France, where he continued to swim and teach. He remarried, and the good humor that he had been known for before the war returned, though he never forgave his erstwhile competitor Cartonnet, whom he believed to the end had betrayed him and his family to the Gestapo. Cartonnet was sentenced to death in absentia by the Court of Justice of Haute-Garonne in March 1945 but twice escaped arrest (by the French and the Italians), only to die in hiding in an Italian monastery in 1967.

Nakache’s swimming pool in Toulouse was formally inaugurated as La Piscine Alfred Nakache in 2018, the Bey of Tunis awarded him the Order of Glory, and he has been inducted into various halls of fame. But he was never decorated by the French state with the Cross of the Resistance Volunteer Combatant. That distinction would not only have been deserved; it would have come with a government pension.

Fittingly, perhaps, Nakache died in the water. He suffered a heart attack while swimming in the port of Cerbère, about one hundred kilometers from the city of his birth. At his request, his gravestone bore not only his own name but those of Paule and Annie.

Suggested Reading

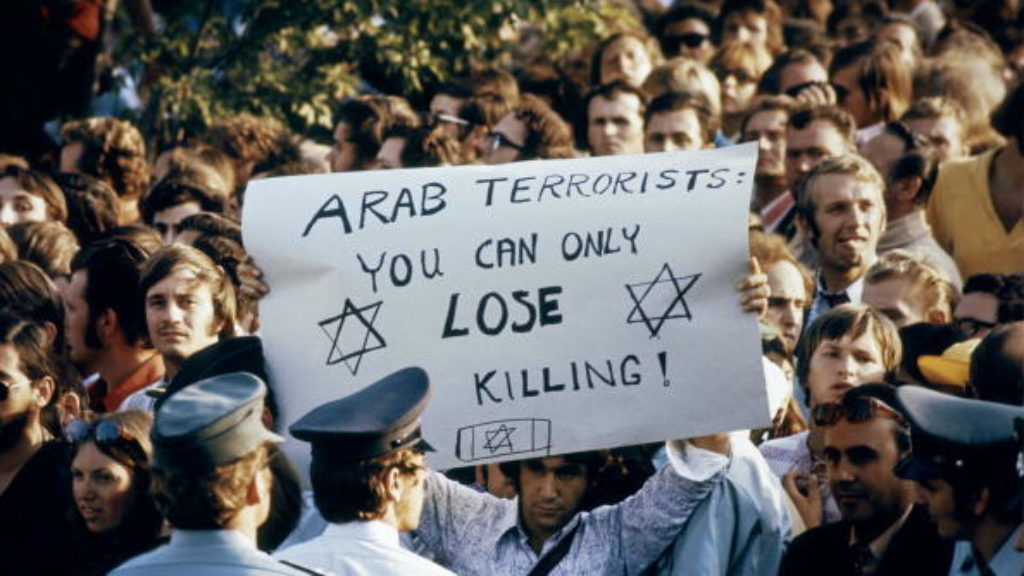

Black September

Organizers of the 1972 Olympic games were determined to avoid recalling Munich's Nazi past—which inadvertently facilitated the bloody massacre of Israeli athletes.

Victim Enough? The Jews of North Africa During the Holocaust

As the Tunisian Jewish novelist Albert Memmi wrote, “I am not enough of a victim; that is why my conscience is tortured.” Must the Jews of North Africa, as contributor Lia Brozgal puts it, write “a history that competes with a more catastrophic one, or be written out of history?”

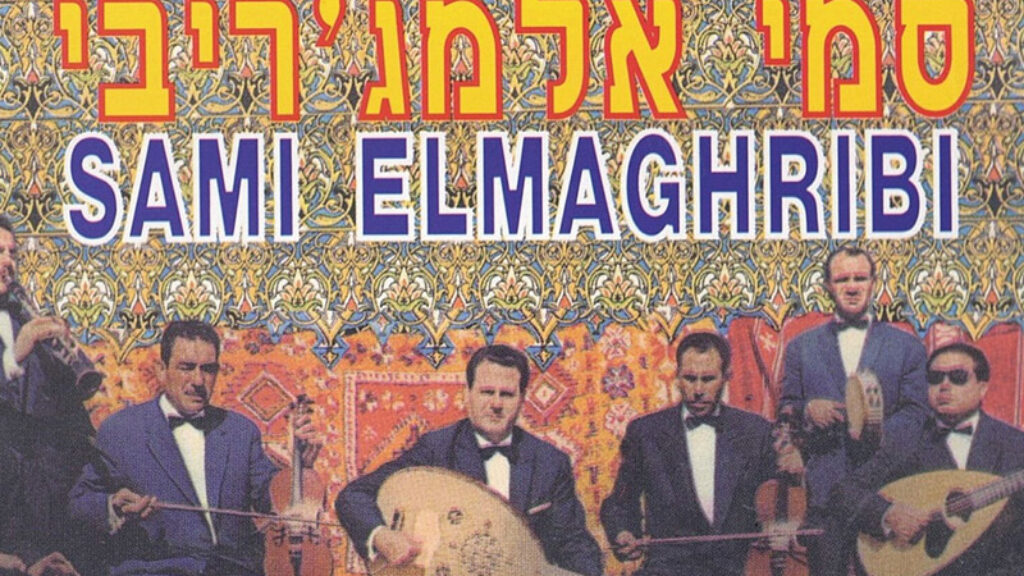

Missing Notes

There was a time when Jewish artists set the tone for North African music, but now only echoes remain.

Memories of Morocco

In the 1940s Moroccan Jews were still sacrificing a bull on the Sultan’s doorstep. There was a deep cultural symbiosis of Jews and Muslims in North Africa.