Their Crowd

Joseph Seligman left his home in Bavaria in 1837, when he was seventeen, and arrived alone in the United States with $100 in the lining of his trousers. America was in the midst of a financial panic brought on by bad loans and a bank run. He quickly went to work as a cashier and a clerk before becoming a reasonably well-paid private secretary to a businessman in an eastern Pennsylvania town called Mauch Chunk (it was later renamed Jim Thorpe, after the famous athlete).

Within a year Seligman had invested his meager savings in small merchandise and set out on the proverbial immigrant Jewish route that led from peddling in the hinterland (mostly in the South) to storekeeping in backwater towns (like Selma, Alabama) to large-scale merchandising to banking. Seligman was the first of the many German-born Jewish “money kings” who populate Daniel Schulman’s richly detailed history. Among his influential friends, he could count Ulysses S. Grant (who was not the antisemite he is usually remembered to have been).

In the summer of 1877, Seligman went on what is perhaps the most well-known and ill-fated vacation in American Jewish history. Together with his entourage, he tried to settle into one of his regular haunts, the posh Grand Union Hotel in Saratoga Springs, but was turned away by the management because he was an “Israelite.” The rebuff immediately became news and led to a vehement battle in the pages of the New York Times between Seligman and the man effectively in charge of the Grand Union, Judge Henry Hilton (no relation to Conrad).

The inhabitants of the “civilized world,” Seligman angrily chided Hilton, “despise intolerance, low cunning, and vulgarity, and will not patronize a man who seeks to make money by pandering to the prejudices of the vulgar.” Vulgarity, however, lay in the eyes of the beholder. According to Hilton, Jews like Seligman “have brought the public opinion down on themselves by vulgar ostentation” and a lack of civility. And what started in Saratoga did not stay in New York. These mutual recriminations found their echoes in “papers as far away as Honolulu” and ultimately resulted in an effective Jewish boycott against the company that owned the Grand Union. Regarded by some historians as the opening shot of full-fledged American antisemitism, the insult to Seligman was, at the very least, as Schulman points out, a harbinger, as “discrimination against the Jews appeared to grow more prevalent and acceptable” in America.

The man who was at the center of this ruckus was a proud Jew, as Schulman explains, but also a rather ambivalent one. Joseph Seligman “remained fiercely loyal to his people, using his political and social influence to garner support for Jewish causes and charities.” He was also active in the leadership of the preeminent Reform institution in New York, Temple Emanu-El, even though he was, at heart, theologically in tune with his friend Felix Adler, the Emanu-El renegade who left Judaism behind and founded the secularist Ethical Culture Society.

In 1880, presiding over Joseph’s funeral service at the Seligman home, Adler lauded the deceased:

He was one of those who believed that a gladder morning is about to dawn for mankind—that the time is nigh when, among the intelligent few, at least, if not yet among the ignorant many, the distinctions of race may be wiped out and the animosities founded on religious differences may be forgotten.

At the same time, an anonymous “well known Hebrew” hailed him in the New-York Tribune as “without doubt the most prominent Hebrew in this city” who did more for his fellow Hebrews “than any other man.” He knew, he said, “of no one who can assume the leadership as he did.” But, as Schulman observes, “the void of leadership . . . would not remain empty long.”

Jacob Schiff was eighteen years old when he landed in the United States on August 6, 1865, twenty-eight years after Joseph Seligman’s arrival. He was only one year older than Seligman had been at that time, but he had five times as much money in his pocket. He had also had a much more comfortable journey and the experience and connections that enabled him to skip the peddling stage and plunge straight into finance—at which he was a natural. One of his first employers said he had “the makings of ‘a born millionaire.’” Within ten years he was able to contribute $50,000 to the banking firm of Kuhn, Loeb & Company, which he joined as a partner, second in influence only to Solomon Loeb, whose son-in-law he became on May 6, 1875. Over the following decades, he took the reins, built Kuhn Loeb into an international powerhouse, and became an extremely wealthy man.

Schiff outdistanced Seligman not only as a banker but as a philanthropist, a fundraiser, and a political leader. He didn’t by any means restrict his gifts and activities to Jewish causes, but it was in their service that he made the biggest—indeed, a colossal—difference. He was crucially involved, among many other things, in the founding and running of New York’s Montefiore Hospital from the 1880s to the end of his life, the main backer of Lillian Wald’s Henry Street Settlement, and the founding president of the Educational Alliance. He played a leading role in the decades-long and ultimately unsuccessful effort to prevent restrictive legislation that would have curtailed the massive immigration of Eastern European Jews to the United States.

At the same time, however, he was keenly aware of the extent to which these poor Ostjuden were the object of social contempt and outright antisemitism and believed that they threatened the status of other American Jews. “New York and the North Atlantic seaports . . . are getting in a state of super-saturation with regard to the Jewish population,” Schiff warned, and “the problems to which the existing congestion gives rise—social, economic, even moral—are, I feel getting beyond our control.” To regain control, he joined forces with the Jewish Territorial Organization’s leader, the British Jewish novelist and playwright Israel Zangwill, and launched the Galveston program. In the decade before World War I, they worked, with great energy but limited success, to divert Jewish immigrants away from Ellis Island to the Texas port, from which they could then proceed into the interior of the United States.

In tandem with his efforts to help migrants, Schiff sought to alleviate the conditions that motivated them to leave the Tsarist Empire for the United States in the first place. Already in 1891, he was meeting with President Benjamin Harrison (together with Oscar Straus and Joseph Seligman’s brother Jesse) to seek his administration’s support for Russian Jewry. Twelve years later, in the aftermath of the Kishinev pogrom, he unsuccessfully badgered Theodore Roosevelt to take punitive commercial action against Russia if it didn’t cease to discriminate against American Jews traveling in its territory.

Soon thereafter, during the Russo-Japanese War, Schiff played “a decisive financial role” by taking up half of a Japanese bond issue at a time when other financiers were unwilling to do so. He spent $25 million (the equivalent of almost a billion dollars today). Schiff took this action at least in part to punish Russia for its treatment of its Jews and received from the Japanese emperor the “Second Order of the Sacred Treasure” for his investment. As the de facto leader of a Jewish delegation meeting with the Russian finance minister during the subsequent peace conference, he made it clear, according to the minister himself, that “unless Russia changed its ways, he would work with all his might to deny the empire American capital.” At the same time, he was (in the words of the journalist George Kennan, the great-uncle of the diplomat and historian George F. Kennan) financing “the propaganda among the Russian officers and soldiers in the prison camps of Japan” meant to turn them against the tsarist government.

Schiff continued to hammer away at the regime he loathed and eventually enjoyed a limited measure of success. In 1911, after failing to convince President William Howard Taft to break the US commercial treaty with Russia, he launched a public campaign through the American Jewish Committee “to mobilize public opinion behind a legislative effort to invalidate the treaty.” It worked. Congress voted overwhelmingly to do so, and the president’s hand was forced. On January 1, 1912, he pulled the US out of the treaty.

Three years later, after World War I broke out, Schiff refused to participate in any loans to the Allies that could possibly benefit Russia, even when that cost Kuhn Loeb dearly. When the Russian Revolution took place, however, Schiff was exultant. Proclaiming the tsar’s fall to be “almost greater than the freeing of our forefathers from Egyptian slavery,” he withdrew his objections to loaning money to the Allies.

Schulman insightfully describes most of Schiff’s nearly countless endeavors among and on behalf of the Jews in America and abroad, and tries to explain his motives for being so intensively engaged in them. For a summation of his rather idiosyncratic religiosity, he relies on one of his grandchildren, Edward Warburg, who noted his grandfather’s odd habit of “concluding his daily worship by reverently kissing a pair of faded photographs of his parents,” his strict observance of the Sabbath, his idiosyncratic deviations from kashrut, and some of his liturgical innovations. “We were not trained in Jewish ritual compliance,” said Warburg, “but in an inimitable Schiff-Warburg form of Familiengefühl (a sense of family) and ancestor worship.” Schulman adds that Schiff viewed his philanthropy as tzedakah. “The term translated not to ‘charity’—a word Schiff disliked—but to ‘justice’ or ‘fairness.’ Unlike charity, there was nothing voluntary about tzedekah. It was a religious requirement to help the poor and needy.”

Schulman also clarifies his position with regard to Zionism. Schiff opposed the creation of a Jewish state, which would make for “a separateness which is fatal” and would cast aspersions on Jews’ loyalty to the states in which they lived:

He believed the future of the Jewish people was in the United States and spoke of an “American Israel” composed of “the children’s children of the men and women who, in this generation, have come from all parts of the globe to these blessed shores.”

There is, however, considerably more to say about Schiff’s Weltanschauung. As his biographer, Naomi W. Cohen, noted a quarter century ago in her superb Jacob H. Schiff: A Study in American Jewish Leadership, Schiff’s friends recognized him to be “a God-fearing man who discerned the finger of Providence in the lives of individuals and nations.” He was no theologian, but he did reaffirm the classical Reform concept of the Jews’ mission to “labor for universal acceptance of the unity of God and brotherhood of man.” To play this role, Jews needed the kind of education that would ensure “that the foundations of our faith . . . may . . . be kept alive and handed down to our children and to coming generations.” Nowhere is his commitment to this continuity more apparent than in the support that he extended to the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS), something that Schulman barely mentions.

Believing that with their abandonment of Old World Orthodoxy, the largely Eastern European “younger element of the Eastside down-town population were losing their moral hold,” while doubting that Reform Judaism could capture them, Schiff subsidized the Conservative institution that would provide them with a more acceptable blend of Judaism and modernity. He became not only the school’s largest contributor but, as Cohen notes, “a familiar figure at JTS.” “Board meetings were held at his home and the school’s investments were handled in his office, but students and faculty met him at social affairs and at annual commencements.”

With Solomon Schechter, the legendary rabbinic scholar who set the path for JTS, Schiff “discussed issues of all sorts, and despite occasional clashes, notably over Zionism, the two quick-tempered men enjoyed each other’s company.” Schiff may not have been a philosopher-king, but he certainly had a reflective side, and many of his actions can best be explained as the product of his conception of Judaism and the Jews’ world-historical significance.

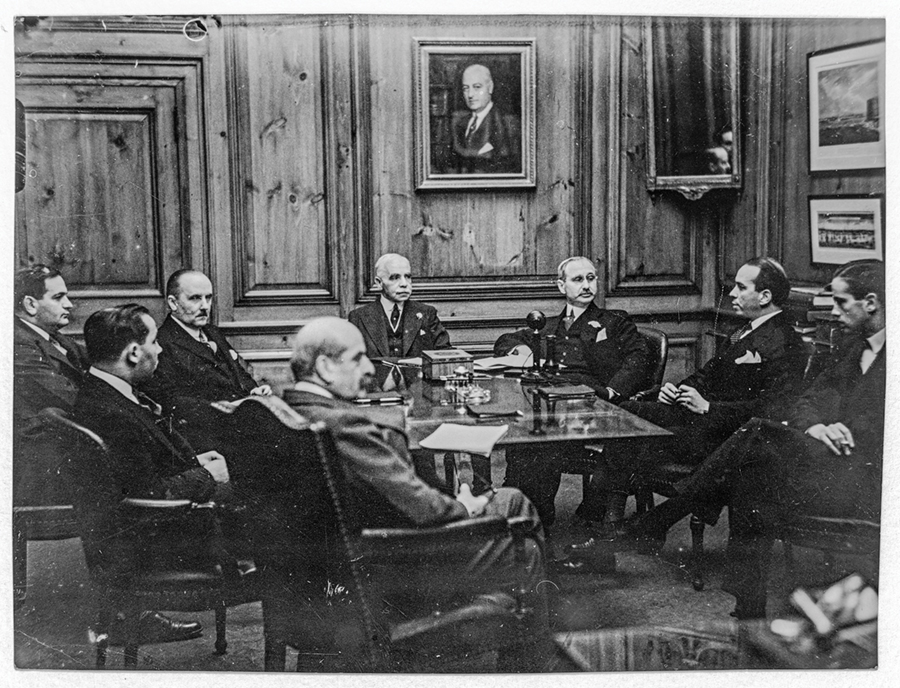

The Money Kings isn’t a biography of Jacob Schiff, yet the singularly influential financier inevitably steals the show. Schiff is the central figure in the photo on the book’s cover and occupies the largest spot in its index as well. Spreading over three pages, his entry dwarfs that of any of the numerous Seligmans, Kuhns, Loebs, Goldmans, Sachses, Lehmans, and Warburgs featured in Schulman’s sprawling and absorbing narrative. This is as it should be. Although he was far from the only American Jewish money king of his generation, he was certainly the first among equals, and it is doubtful that the rest of the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century figures Schulman describes would have registered in anyone’s mind as some kind of royalty if Schiff hadn’t been numbered among them.

Still, they were an extremely impressive bunch, none more so than the Warburgs, whose illustrious family history was chronicled three decades ago by Ron Chernow in a massive bestseller on which Schulman necessarily relies. Schulman gives respectful attention to the sons of the Hamburg banker Moritz Warburg who achieved fame in Europe (in very different ways), but his main concern is with the two who migrated to America. Both Paul and Felix Warburg married the daughters of Kuhn Loeb partners and joined the firm themselves. Paul, who married Nina Loeb in 1895, was a “brilliant banker and financial theorist” who became extremely close to Schiff and, in time, played a crucial role in establishing central banking in the United States. He left Kuhn Loeb in 1914 to serve as one of the original members of the Federal Reserve Board and before long became its vice governor.

Felix, who became Jacob Schiff’s own son-in-law in 1895, was no banking genius, but he was successful nevertheless and led “a frenetic life of charitable service” to many causes, including some of Schiff’s favorites. Even Schiff himself thought he was “overgenerous.” On the other hand, Felix’s own son Gerald couldn’t quite understand why he was so devoted to these causes, since “he disliked almost everything about the Jews except their problems.”

Schulman is much more focused in detailing (but not theorizing very much about) how his subjects “played a pivotal part in America’s progression into a financial, and thus global, superpower” than on illuminating a chapter in Jewish history. And he doesn’t seek, in the end, to evaluate the overall contribution that they made to the shaping of contemporary American Jewry (to which, as he indicates, their descendants by and large don’t belong). He does, however, highlight the enduring impact of their activities on the outlook of antisemites in America and elsewhere.

The Protocols of the Elders of Zion was already in circulation by the time Jacob Schiff launched his war against tsarist Russia, but it is hard to imagine any better grist for the mill of those who disseminated it than an American Jewish money king undermining the Russian old regime. So it isn’t a surprise that in the 1920s,“Schiff and his partners featured regularly” in Henry Ford’s Dearborn Independent, “their activities—philanthropic, financial, political—refracted through a sinister lens and depicted as wily machinations in service of some Jewish master plan.” Even today, Schulman writes:

Google “Schiff,” and it will become evident what Ford—and Boris Barsol, whose intelligence memo [spuriously] linking Schiff to the Bolshevik revolution leaked to the press in 1925 and whose relentless promotion of the Protocols stoked antisemitism the world over—helped to unleash. Schiff, along with his Warburg in-laws, would feature in pernicious conspiracy theories concerning their role in the Russian Revolution (and other nefarious acts) that have grown more grandiose with the passage of time.

Needless to say, a book like The Money Kings can do very little to uproot such nonsense, but it does tell the true story that lies behind the badly distorted version that is widely disseminated. Schulman has given us a panoramic group portrait of half-forgotten but uniquely significant American Jewish leaders.

Suggested Reading

Then and Now: Two Wars

Allan Arkush spent the Yom Kippur War delivering medical supplies in Israel. Fifty years later, he finds uncanny comparisons between the current war and World War I.

Joseph the Righteous

But on the very night in 1737 that Joseph Süss Oppenheimer’s patron suddenly passed away, he, “his servants, and many other court officials were arrested, and soon a special inquisition committee was convened in order to investigate the court Jew’s ‘atrocious crimes.’”

The Rothschilds of the East

The Splendor of the Camondos and the pity of it all.

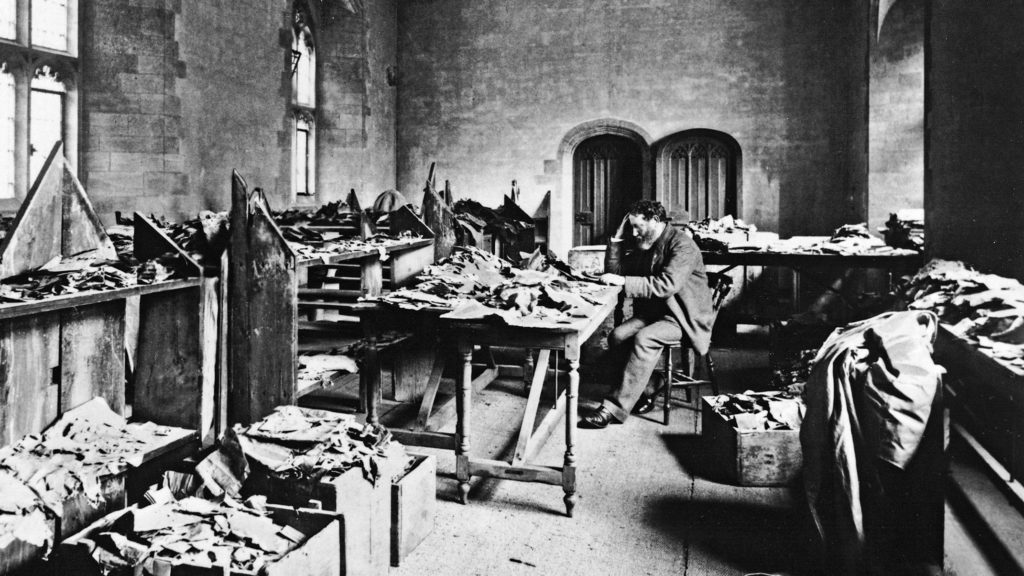

Buried Treasure

Hundreds of thousands of Jewish manuscripts were redeemed from Egypt.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In