Joseph the Righteous

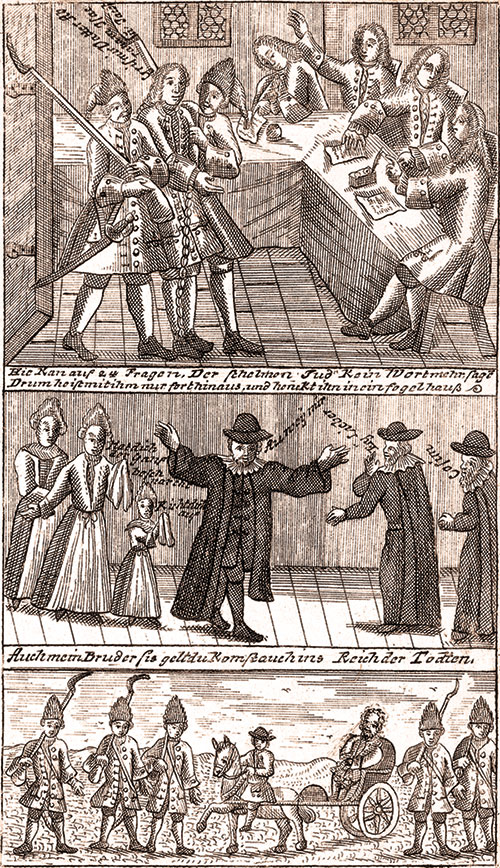

In keeping with his book’s title, Yair Mintzker hasn’t written a life of Joseph Süss Oppenheimer, the famous “Jud Süss” whose sensational rise and sudden, catastrophic fall in the German Duchy of Württemberg came to epitomize the perilous careers of court Jews in early modern Central Europe. Given the numerous published biographies of Oppenheimer, particularly the influential 1929 study by Selma Stern as well as more recent exhaustive reconstructions by historians Barbara Gerber and Hellmut G. Haasis, this is wise. Instead, Mintzker gives us what he somewhat ponderously calls a “polyphonic history” in which he presents Oppenheimer’s year-long investigation, trial, and execution, in 1737–1738, from the conflicting perspectives of his contemporaries.

Mintzker rightly insists that despite the extensive research of previous scholars Oppenheimer himself has remained an elusive figure. This is not because he was particularly mysterious or wished to cover his tracks, but rather because the extant documents stemming from the period of his ordeal simply do not allow him to speak in his own voice. But Mintzker does much more than expose the biased nature of the sources that have colored our inherited view of Jud Süss. He does something quite remarkable: He affords us detailed and often surprisingly sympathetic accounts of those who shaped Oppenheimer’s image to suit their own interests, needs, and perspectives.

It is true that, at times, this Rashomonic approach leads Mintzker to lose sight of his stated narrative purpose, so smitten is he with uncovering the curious details of these individuals’ lives. In fact, Mintzker is intermittently aware of this tendency and even occasionally defensive about it, but he needn’t be. For if at times Oppenheimer serves merely as the occasion, or the pretext, for these portraits, the result is no less fascinating.

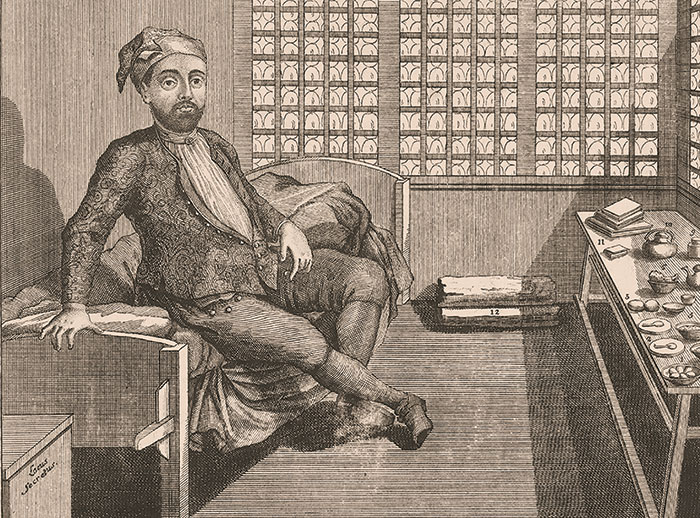

Joseph Süss Oppenheimer was one of the later representatives of the phenomenon of the “court Jew,” which had its roots in the 16th century and flowered in the period following the Thirty Years War. The proliferation of large and small states following the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, along with the war’s decimation of population and property, created an urgent need on the part of Central Europe’s new rulers for capital and credit. Jews, who had been excluded from most of Central Europe by the time of Luther’s death in 1546 (and in many places much earlier), were now invited in small numbers to come back as creditors, financiers, minters, crown merchants, and military suppliers. They weren’t popular, which isn’t surprising given that they were both stigmatized aliens and willing tools of new absolutist states which were seeking to bypass the fiscal authority of estates, guilds, and other traditional institutions. This made the court Jew and his retinue entirely dependent on the ruler’s protection—and uncertain continued favor.

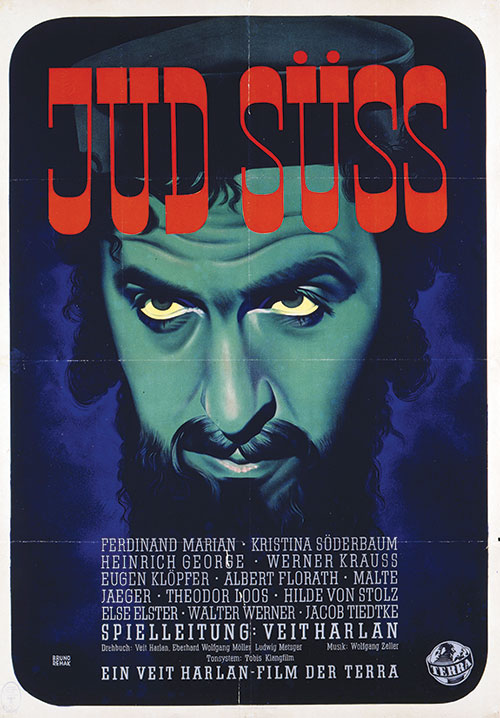

Mintzker uses the term court Jew quite loosely to encompass even fairly modest merchants. But the popular mind associates this type with such striking figures as Leffmann Behrens, who became the unofficial finance minister to Prince-Elector George Louis of Hanover (later King George I of Great Britain), or mightier still, Samuel Oppenheimer, the financier and military supplier of the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, whose logistical genius proved crucial in routing the Turks amassed at Vienna’s gates in 1683. Like Joseph Süss, Samuel Oppenheimer’s services to the state did not in the end avail him. An angry mob and an ungrateful emperor despoiled his estate and seized his fortune before the dust could settle on his grave. But Joseph Süss with his miserable fate stands out even in comparison with such wealthier and more powerful predecessors—and not only because of the notorious film the Nazis made about him in 1940.

For one thing, during his rise Joseph Süss all but failed to pay the kind of lip service to traditional Jewish religious observance that the Jewish community expected of court Jews. Worse still, his aristocratic pretentions, numerous reported affairs, and overt political interventions threatened the fragile security of Württemberg’s fledgling Jewish population. In spite of these things, Oppenheimer’s refusal to renounce Judaism on the eve of his execution turned him into a genuine if unlikely martyr for some contemporary Jews. And his earlier insistence on residing outside of Frankfurt’s famous ghetto as well as his religious skepticism and haughty arrogance toward Gentile authority have won him the grudging admiration of many modern Jews.

Oppenheimer enjoyed five successful years as the court Jew of Duke Carl Alexander of Württemberg. But on the very night in 1737 that his patron suddenly passed away, he, “his servants, and many other court officials were arrested, and soon a special inquisition committee was convened in order to investigate the court Jew’s ‘atrocious crimes.’” His accusers blamed him for the sidelining of old councilors and the creation of “a secret cabinet whose members he himself had advanced despite their notorious characters.” Their 80-page summary of the incriminating “facts” concluded, however, with less political and more damning charges:

He nourished himself only on robbery and treachery, and indeed often made it known throughout the land how he lived almost like a prince, engaging in prostitution, fornication, and possibly also incest, all extremely insolently, and sometimes even with Christian women.

There is, indeed, no denying that Oppenheimer had his share of Christian mistresses, but the year-long investigation into his misdeeds was essentially a frame-up. Even some Christians expressed doubts about his guilt at the time. Duke Carl Alexander’s son went so far as to label his trial a “judicial farce.”

Mintzker himself agrees, but his purpose is not to debunk the trial so much as to follow its crosscurrents. He does this by devoting a chapter to each of four figures who in different ways were connected with the proceedings: Philipp Friedrich Jäger, the legal inquisitor assigned to interrogate and draw up charges against Oppenheimer; Christoph David Bernard, a Jewish convert who wrote a pamphlet claiming to record his conversations with the condemned prisoner and his failed efforts to get him to accept Christ; Rabbi Mordechai Schloss, a Jewish business rival who sponsored a hagiographic Hebrew-Yiddish pamphlet about Oppenheimer after his hanging; and finally, David Fassmann, an adventurer, serial liar, and later best-selling author of numerous “dialogues of the dead,” reminiscent of the classic Steve Allen 1970s television show, Meeting of the Minds, in which famous and infamous past notables came together in the afterlife to argue and gossip. Unlike the other three, Fassmann was not involved in the trial, nor did he know Oppenheimer personally (although Oppenheimer appears to have owned at least one of Fassmann’s books). But Fassmann was intrigued by Oppenheimer’s precipitous fall and featured him in successively less flattering portrayals in three of his dialogues. How the members of this motley assemblage made use of Oppenheimer’s trial comprises the real core of this engaging book.

The chapters on Bernard, and especially those on Jäger and Schloss, are superbly rendered. Mintzker is not only a masterful historical researcher, he is a penetrating psychologist. His portrait of Jäger is a damning reconstruction of a zealous prosecutor determined to find a smoking gun where none existed. This was not just out of a misplaced sense of duty but in order to try to fulfill his own youthful promise that had, by the time of the Oppenheimer investigation, begun to fade. Though he resists reducing any of these personalities to social types, Mintzker rightly situates Jäger’s hatred of Oppenheimer in the context of the declining fortunes of his professional class, the learned bureaucratic stratum of premodern Germany whose traditional privileges were by then eroding. But more precisely, Mintzker ties Oppenheimer’s ordeal to the sensational trial of the previous duke’s ex-mistress, three years earlier, in which Jäger had humiliatingly failed to win a conviction, in part due to Oppenheimer’s intervention. To guarantee that he would not make the same mistake twice, Jäger personally interrogated Oppenheimer on 45 separate occasions. He knowingly violated judicial norms he had sworn to uphold through the misuse of evidence and the badgering of witnesses, and he even pushed hard for judicial torture when some of the other investigators proved more squeamish. As with many in his position, before and since, personal ambition and righteous indignation (much more than anti-Semitism, according to Mintzker) were inextricably entwined in Jäger’s furious campaign to see Oppenheimer hang.

Given that he paper trail on Rabbi Mordechai Schloss is skimpier than on Jäger, Mintzker’s reconstruction of the complex motives behind his efforts to vindicate Oppenheimer after his execution seem even more impressive. Schloss had been a court Jew in Württemberg and had his share of problems as well. In 1729 he and his son Moshe had been imprisoned for a month because of a fellow Jew’s complaint about the inferior quality of the wallpaper they delivered. Oppenheimer’s rise to power, a few years later, seems to have coincided with his own fall from grace. When he was called before the committee that was investigating Oppenheimer, Schloss “insisted that ‘he does not want to say anything that might hurt Süss, God forbid, because Süss had done him neither harm nor good.’” In almost no time, however, he shifted his ground and claimed “that Oppenheimer had always been a person about whom ‘no one had anything good to say.’” By the end of his deposition, he “supported the claim that Oppenheimer had stolen from the prince’s own purse as well as from the state’s and the estates’ coffers.”

Despite the key role he played in destroying Oppenheimer’s life, Schloss helped his soon-to-be son-in-law publish a book called The Story of the Passing of Joseph Süss, May the Memory of the Righteous Be for a Blessing. “It is,” Mintzker tells us, “the only document we know of that was composed by Jews in the immediate aftermath of the execution, and it told Oppenheimer’s story from an overall very sympathetic perspective.” The Story depicts Oppenheimer as a sinner who sincerely repented in prison and “whose soul departed in sanctification of the Lord’s name.”

What was Schloss up to? “The stark contrast between Schloss’s September deposition and the post-execution account could indicate a sense of guilt on Schloss’s part,” but The Story might point to other things as well. Its account, for instance, of “Joseph the Righteous,” as Oppenheimer is called in the text, made even semieducated Jewish readers think of the biblical Joseph:

Some of the Yiddish accounts of Joseph’s story portray him as a victim of false allegations. They emphasize that it was Potiphar’s wife who tried to seduce Joseph, not the other way around. If Schloss and Seligmann tried to invoke this particular interpretation in The Story, they engaged in what we may roughly call the inversion of the inquisition committee’s account: rather than Oppenheimer being a rapist (as Jäger, for instance, tried to suggest), Schloss and Seligmann represent him as an innocent victim of rape allegations.

Although he is a specialist in early modern German history, Mintzker understands the principal texts and touchstones shaping premodern Jewish mentalities, as this suggestion and his further reflections on the esoteric meaning of The Story amply demonstrate. He recognizes that Jewish vulnerability in this period was not only a function of overt anti-Semitism but of the way in which the legal status of Jewish communities could depend on the economic utility and shifting fates of individual court Jews. “What held their community together,” he astutely notes, “was not harmonious consensus or common practices, but individual and highly insecure commercial opportunities at a prince’s court. Theirs was above all a community of risk.” Reframing the story of Joseph Süss as that of the biblical Joseph helped the Jews of Württemberg cope with that risk.

The single serious flaw in The Many Deaths of Jew Süss is the author’s insistence that what is really a virtuoso scholarly performance is also a methodological breakthrough. Mintzker seems to have convinced himself that the kind of historical perspectivism he has practiced here is virtually unprecedented. Modern historical writing, he argues, has remained tethered to an outmoded 19th-century realist style, when historians really should write more like “Woolf, Faulkner, Joyce, and Beckett.” Perhaps it is in pursuit of this goal that Mintzker punctuated his narrative with stilted dialogues in which an imaginary reader challenges the author to defend his interpretations. Unfortunately, this doesn’t give one a sense of high modernist dialectical tension, it only guarantees that, one way or another, Mintzker emerges triumphant from every argument.

In the book’s conclusion Mintzker advances a final claim that even while patently contradicting his initial premise admittedly cannot be denied. The variety of perspectives of Joseph Süss Oppenheimer that Mintzker has explored, with all their ineliminable distortions, do give us revealing glimpses of the actual man in all his human pathos. That is a worthy enough accomplishment.

Suggested Reading

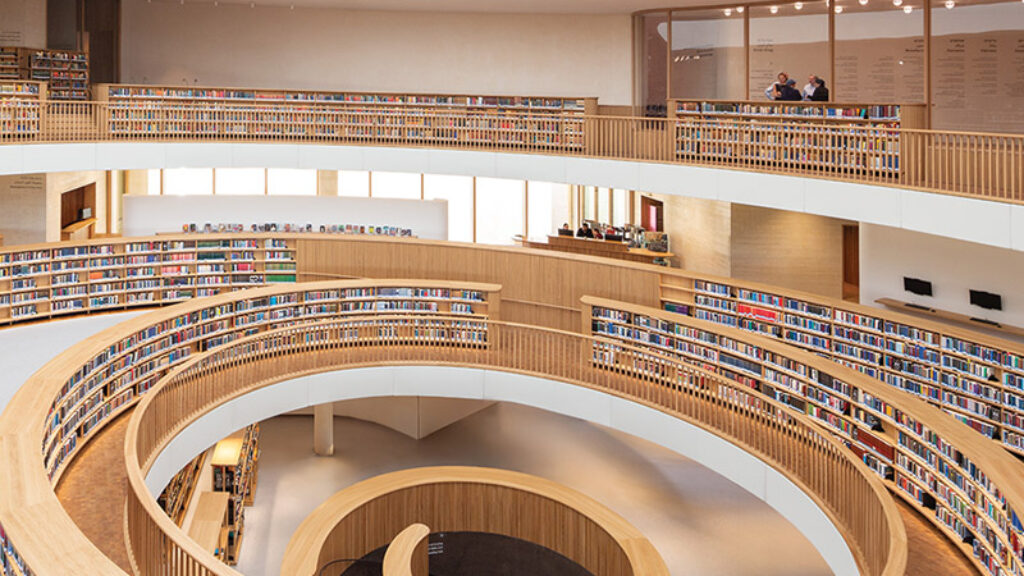

This Great House

Israel's new National Library is the most architecturally exquisite building erected in the history of the Jewish State. Like its predecessor, it’s also an excellent place to “hock” about books and ideas.

On Old Stones, a Black Cat, and a New Zion

There is a legend that Prague’s Altneuschul was built on a foundation of stones from the ancient Temple in Jerusalem.

Wild Things: The New Neo-Hasidism and Modern Orthodoxy

Who are Joey Rosenfeld and his pseudo-Hasidic pranksters, and what does their success have to do with the future of Modern Orthodoxy?

Samson Raphael Hirsch’s Attack on Liberal Christian Bigotry and American Slavery

In 1841, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch leapt into a raging debate between liberal and orthodox Protestants, declaring, “It is high time for the non-Jewish thinker to set aside convenient pre-judgements and to begin to construct Christendom without having to destroy Judaism.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In