Then and Now: Two Wars

Fifty years ago, Israel’s enemies attacked it on Yom Kippur, but the war lasted through all of Sukkot. On one of the middle days of the holiday, I found myself sitting in a Kupat Cholim delivery truck, behind Dr. Odzeh, the physician accompanying our small team of volunteers as we hauled boxes of medical supplies to a Jerusalem clinic. Odzeh’s regular driver and his assistant had been drafted, as had nearly every other able-bodied young man in the city—apart from those who were Arabs, haredim, or foreign students like me. At one point we drove past a gaggle of religious young men, each carrying a lulav. “God-damned lulavs,” Odzeh muttered contemptuously. “All they care about is their God-damned lulavs.” His own son was in the Sinai.

I thought about Odzeh a couple of weeks ago when I read that fifteen hundred Orthodox men had just volunteered to serve in the IDF, and that the army, pleasantly surprised by this development, was investigating the possibility of integrating them right away, perhaps as drivers and shleppers. They might even take up jobs like the one I once had, I thought, and I wondered what Odzeh would have said about them if they had shown up for work at the warehouse he supervised in Tel Arza.

On the Black Sabbath of October 7, 2023, the idea of volunteering again didn’t cross my mind. I’m too old and too far away. My job now is to teach Jewish history, including a course on World War I and the Jews. As preoccupied as I am with the ongoing war, I have to focus on the one that ended more than a century ago, and, inevitably, I often find myself thinking about each of them in the light of the other.

They are vastly different of course, these two wars. But they both included pogroms. October 7 was a day of pogroms, and reminded everyone who knew anything about Jewish history of the most horrible of them. One of the leading scholars of Israel studies, Ilan Troen, wrote a widely-read piece bearing the haunting title: “My grandmother was killed in a pogrom. Then my daughter was, too.” Troen’s grandmother died near Rovno in 1919, after World War I ended, one of as many as 150,000 Jewish victims in a wave of pogroms that took place during the Russian Civil War. His daughter and her husband were murdered at Kibbutz Holit on the Gaza border on October 7 while protecting their son, who survived.

Jeffrey Veidlinger’s recent book, In the Midst of Civilized Europe: The Pogroms of 1918-1921 and the Onset of the Holocaust, vividly retells the story of the largely forgotten atrocities perpetrated in the chaos after World War I. My own maternal grandparents were on the scene for one of them, near Kiev, but survived and came to the U.S. shortly afterwards. What happened on October 7 made me think first, however, not of these pogroms but of some that took place a few years earlier, under the auspices of the Russian Army; first in occupied Galicia, and then in Russia itself, during the early stages of the war.

In the course of their briefly successful invasion of Austrian territory, Cossacks and other Russian forces did hideous violence—often rivalling the savagery of Hamas—to local Jewish communities, hoping to “drive them to the Krauts.” Hundreds of thousands of Jews indeed fled westward to Vienna and other parts of the empire. Those who remained in place were treated with deep suspicion and brutality by the invading army. Occasionally, the Russian authorities took their local leaders hostage, threatening to execute them if any local Jews at all were caught spying against them.

Soon forced by the Austrians’ German ally back across the border and deep into its own territory, the retreating Russian Army treated its own Jewish citizens no differently. It forced hundreds of thousands of them eastward into Russia, away from the battle zone, where they supposedly constituted a threat to their own country, despite the fact that hundreds of thousands of their relatives were then serving in uniform. Again, many local Jewish leaders were taken hostage and threatened with execution. Most of them eventually returned home safely. I hope (against hope) that, before long, we can say the same of all of our own hostages in Gaza.

On October 16, after most commercial airlines had suspended their flights to Israel, the Royal Caribbean cruise ship Rhapsody of the Seas pulled into Haifa harbor. The United States government had arranged for it to transport American citizens who wanted to leave the country to Cyprus (at their own eventual expense). That reminded me of another American ship that had once docked at a nearby port in wartime. It was there not to pick up stranded Americans, however, but to deliver money.

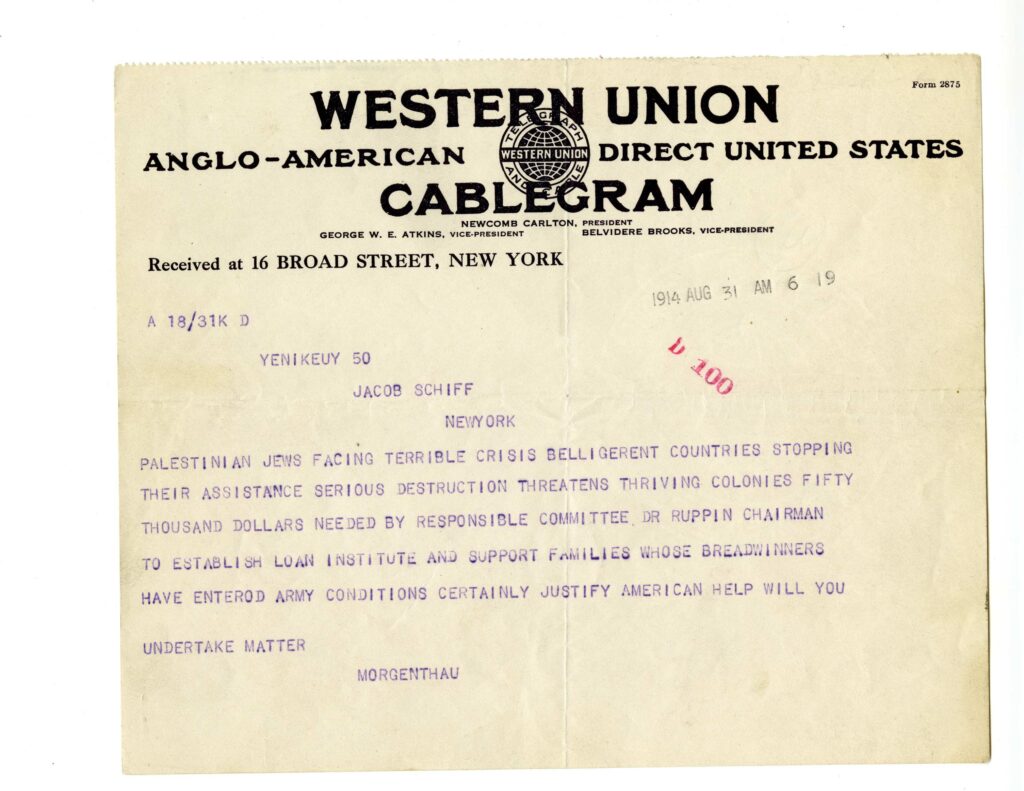

In August 1914, the Jewish community in Palestine found itself suddenly cut off from its European supporters. Arthur Ruppin, who headed the World Zionist Organization’s Palestine Office, estimated that the Yishuv needed at least $50,000 in order to survive. But where was that money to be found? Mordechai Hillel Hacohen, one of the leaders of Tel Aviv (and Ahad Ha’am’s mechutan), wrote at the time that “America is the only country that can come to our aid now.” The leaders of the Yishuv turned to the US ambassador to Turkey, Henry Morgenthau, who contacted Louis Marshall of the American Jewish Committee, which supplied half of the money and raised the rest of it from the great financier and philanthropist Jacob Schiff and the notable but not quite as munificent owner of Macy’s, Nathan Straus. Marshall requested Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan to send a relief ship to Palestine.

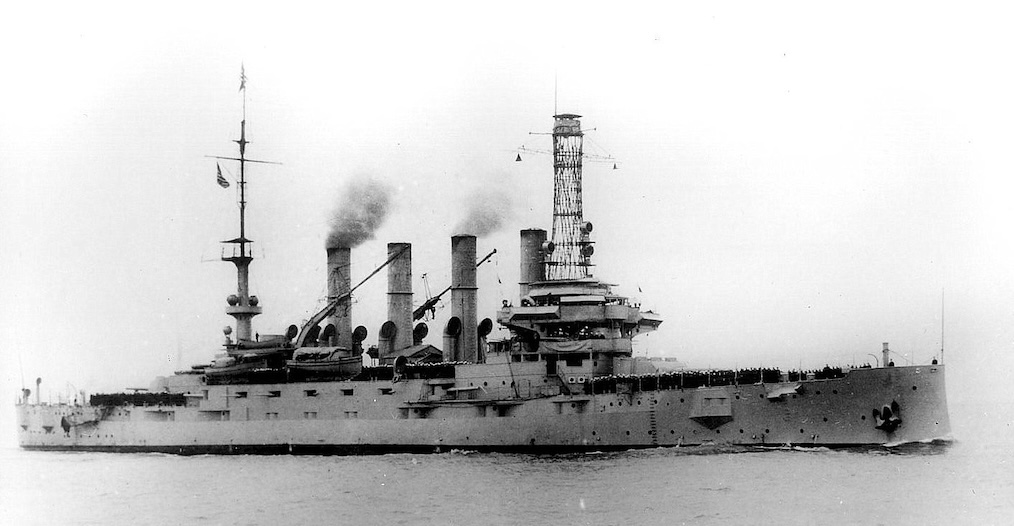

On September 24, 1914, the American battle cruiser North Carolina sailed into Jaffa harbor. On board was Maurice Wertheim, Ambassador Morgenthau’s son-in-law (and the father of the historian Barbara Tuchman), carrying $50,000 in gold. “There was a large crowd on the land-station to witness the scene,” Ruppin reported to Morgenthau. “The fact that the son-in-law of the American Ambassador on board an American cruiser has brought subsidies from the United States for the Jews of this country has deeply impressed the Palestinian population.”

In 1914 the US sent one battleship, carrying money. In 2023, as the vastly increased number of Jews in the Land of Israel faced an altogether different set of difficulties, it has sent two aircraft carrier strike groups—not to mention all of the military aid that has already arrived and will soon be on its way.

Morgenthau, Marshall, and Schiff put themselves out for the Yishuv not because they sympathized with Zionism but in spite of their distaste for it. They all saw themselves as Americans of the Jewish faith, but they all felt links with their coreligionists everywhere that were more than a matter of religion and overrode political differences.

From August 1914 onward, the World Zionist Organization, fully aware of the conflicting loyalties of its diverse constituencies and sensitive to the dangers they faced, maintained a position of strict neutrality in the war. The hopes and efforts of its leaders were focused not on obtaining Palestine through an alliance with one belligerent or another, but through the decisions of the peace conference that would inevitably follow the conclusion of the war. Yet some very important figures within the movement, including Chaim Weizmann and Vladimir Jabotinsky, broke with this policy and aligned themselves with Great Britain in the hope that it would give the Promised Land to the Jews in exchange for their support.

Weizmann and Jabotinsky helped to pave the way for the Balfour Declaration. But in the course of doing so, they had to overcome the spirited opposition of highly placed and patriotic British Jews who felt that the Zionist project cast a dangerous shadow over their world. The most prominent of them was Edwin Montagu, who in the summer of 1917 became the Secretary of State for India. Months later, he complained to Prime Minister Lloyd George: “If you make a statement about Palestine as the National Home for Jews, every anti-Semitic organization and newspaper will ask what right a Jewish Englishman, with the status at best of a naturalized foreigner, has to take a foremost part in the government of the British Empire. . . .”

Compare such self-conscious fear with what Secretary of State Anthony Blinken’s said at a joint press conference with Prime Minister Netanyahu in Tel Aviv on October 12:

Mr. Prime Minister, I’m grateful to be back in Israel in this incredibly difficult moment for this nation—but, in fact, for the entire world.

If you’ll permit me a personal aside, I come before you not only as the United States Secretary of State, but also as a Jew. My grandfather, Maurice Blinken, fled pogroms in Russia. My stepfather, Samuel Pisar, survived concentration camps—Auschwitz, Dachau, Majdanek.

So, Prime Minister, I understand on a personal level the harrowing echoes that Hamas’s massacres carry for Israeli Jews—indeed, for Jews everywhere.

Blinken went on to say that he also spoke in his capacity as a husband and a father, without bothering to insist that he was above all an American. He didn’t feel any need to preempt a charge of dual loyalty. And I haven’t heard any since he made these remarks (though I’m sure that if I dug deeply enough through the Internet I would find more than one).

America was a different kind of place back in 1914. A Jewish Secretary of State was, of course, inconceivable, no matter how little or much he identified with his people. And everyone was supposed to think of America first. President Woodrow Wilson insisted on this from the moment that World War I commenced. On August 19, 1914 he noted that

The people of the United States are drawn from many nations, and chiefly from the nations now at war. It is natural and inevitable that there should be the utmost variety of sympathy and desire among them with regard to the issues and circumstances of the conflict. Some will wish one nation, others another, to succeed in the momentous struggle. It will be easy to excite passion and difficult to allay it. Those responsible for exciting it will assume a heavy responsibility, responsibility for no less a thing than that the people of the United States, whose love of their country and whose loyalty to its Government should unite them as Americans all, bound in honor and affection to think first of her and her interests, may be divided in camps of hostile opinion, hot against each other, involved in the war itself in impulse and opinion if not in action.

Such divisions among us would be fatal to our peace of mind and might seriously stand in the way of the proper performance of our duty as the one great nation at peace, the one people holding itself ready to play a part of impartial mediation and speak the counsels of peace and accommodation, not as a partisan, but as a friend.

President Wilson wanted to keep the United States out of the war, and he also wanted to keep the war from turning the people of this country against one another. Our current president has not been neutral in the present conflict. “The United States stands with you,” Joe Biden has repeatedly told the people of Israel. Support for Israel, he clearly believes, is not only right but in America’s best interest. And a majority of Americans seem to feel the same way.

But for how long? The leaders of Germany, in August 1914, declared a Burgfrieden, a “civic peace” which cancelled all internal divisions among the citizens of the country as long as the country faced an emergency. Even antisemites took this seriously, for a time. But as victory proved elusive, the war dragged, and the hardships of living in a besieged state mounted, the need for a scapegoat increased—and the Jews, of course, fit the bill. More and more people came to believe that they were shirking their duty and making money from the war. This laid the ground for the accusation that they had “stabbed Germany in the back”—a canard whose impact during the postwar period is all too well known.

We don’t know where the war between Israel and Hamas is going, who is yet to join it, and how it will end. We in the diaspora worry above all about the effect it will have on Israel, but we can’t close our eyes to the fact that it has already led to an unnerving multiplication of antisemitic incidents in many countries, including the United States, where divisions of the kind Wilson feared are now present and are evidently growing as many on the progressive left and many Arab Americans denounce Israel with increasing ferocity. The precedent of World War I reminds us that wartime tensions can play out disastrously.

So what are we supposed to do? Last year I wrote an article that focused, in part, on American Jewry’s response to the plight of Russia’s Jews in December 1915. I described how the organizers of a fundraiser for “the suffering Jews in the war zones” packed Carnegie Hall with 3,500 people, leaving another 3,000 unable to enter the building. They raised $600,000 that night. One of my relatives, who very actively raises money for Jewish causes, read the piece and marveled that there was once an American Jewish community that could be counted on to react so strongly. A year ago, these Jews of a century ago looked unmatchable. But, in the wake of the horror of October 7 and the war which has followed, American Jews, despite our internal divisions and with notable exceptions, may now be rising to the challenge.

Suggested Reading

From the Great War to the Cold War

The facts of Hans Kohn’s life are so extraordinary that it almost seems as if the first half of one remarkable figure’s biography had been spliced together with another’s in the second part.

What the U.S. Can and Can’t Do in the Middle East

Why the realists are being unrealistic about American power in the Middle East.

Time Ticks Away in Portugal

Tens of thousands of Jews made their way into Portugal in waves between the fall of France in 1940 and the end of World War II. The ordeals Marion Kaplan depicts were not terribly long, but to the people who endured them, they often seemed endless.

Passover on the Potomac

As the holiday of freedom approaches, we explore two haggadahs—one old and one new—from our nation's capital, and think about the "audacious hope" of redemption.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In