Bind Them as a Sign: A Photo Essay

Since the fall of communism in 1989, Jews have been traveling to Poland in increasing numbers to pray in its famous synagogues, to visit its historic burial grounds, and to search for and daven at the graves of great rabbis. Over the last decade, the presence of Hasidim in some of the country’s cities, towns, fields, and forests has become a not uncommon sight. The homecoming of Hasidim to Poland is a spectacular development, one that is best captured by meticulous documentary photography.

Agnieszka Traczewska is an accomplished film producer and photographer who has spent the better part of the last fifteen years documenting the travels of Hasidic Jews in Poland and beyond. Traczewska is not herself Jewish, but she is Polish, and her interest in Hasidim is animated by the palpable absence of the Hasidic communities that were once a vibrant part of life in her country. Traczewska has overcome many hurdles in pursuing her subject, including winning the trust of her subjects, who maintain a strict separation between the genders and are wary of outsiders and their gazes. She has also resisted the pull of cliché in the overdetermined imagery of Hasidic portraiture. Over the years, Traczewska has developed lasting friendships with Hasidim, leading to what can be described as ongoing collaborations with her subjects. She is respectful of Hasidic life, always entering the field dressed modestly, but she also comes as she is, without effacing her “goyishness” (even on assignment she normally leaves her striking blond hair uncovered). The resulting images are small miracles born of hard-won access, exceptional forbearance, and a deep interest in her fellow human beings.

While her chiaroscuro style mirrors the Eastern European aesthetics of her subjects, Traczewska does not share their reticence about photography. Her profiles capture what Emmanuel Levinas called the “straightness of the face, its directness, its defenselessness.” In the three books of photos that she has published thus far, Traczewska follows a series of yahrzeit pilgrimages in Poland (Returns, 2018), widens the frame to document the revival of Hasidic life on four continents (A Rekindled World, 2021),and narrows it again to focus on the quiet survival of contemporary Orthodox Jewish life in her hometown of Krakow (Kroke, 2023).

Recently, Traczewska photographed a factory in Krakow in which leather used to make tefillin straps is manufactured. The business is owned by the Sonnenfelds, a family of Jerusalem-based Gerer Hasidim who regularly rent the factory floor for brief stints of intense work, and employ a small, international team of Hasidim, along with some local Polish workers. Mordechai, the family patriarch, established the business some ten years ago in Krakow primarily for commercial reasons. Still, its location in southeastern Poland, close to the famed Remuh Synagogue and Cemetery and a few hours journey from Góra Kalwaria, where some one hundred thousand Gerer Hasidim flourished prior to the Holocaust, is meaningful to him.

Tefillin are remarkable pieces of religious technology that bind sacred text to physical body, and they require a high level of expertise and precision to produce. The biblical passages are painstakingly written by expert scribes on parchment made from kosher animal skins. These texts are then sealed in black leather boxes that are adorned with black leather straps, which connect the casings to the body.

One of the features of the rules governing tefillin production is that they must be the product of intentional human effort. Ideally, every component used to make tefillin must be produced expressly for that holy purpose, from the divine names in the biblical passages, which should be written with special intent, to the tanning of the leather to make the straps. Intention is, of course, a human art, so the use of machines in tefillin production can be halakhically tricky. Indeed, the term “tefillin factory” is something of a misnomer. The Sonnenfelds and their workers strive to produce an entirely handmade product, and they avoid automation of any kind. When they feed the hides into the drum, add lye and other ingredients to treat them, and—after the tanning is complete—blacken the leather with a special, kosher dye, they declare that all these actions were undertaken “for the dedicated, holy purpose of tefillin.”

Great care is taken to avoid accidental, and therefore disqualifying, splashes on the leather. Even the gigantic drums in which the hides are treated must, the Sonnenfelds hold, be rotated by human effort. To that end, the Hasidim ride stationary bikes that power the rotating drums.

Traczewska’s photographs capture the arduous and complex labor of producing the leather which will be used for the tefillin straps. The concentrated pride on Mordechai and his coworkers’ faces as they monitor the pH levels, immerse the leather in the dye, and triumphantly remove the gleaming finished product from the vats, is arresting. The Hasidic workers engaged in the messy tanning process glow against the grimy background of the Polish factory, testifying to the presence of holiness even in dark places. Rather than a pitched battle between man and machine—a favorite theme of European painting in the wake of the industrial revolution—Traczewska’s photographs depict a remarkable alliance between the tefillin makers and the factory equipment as they produce the wondrous ritual objects that will link the word of God to the bodies of the faithful.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

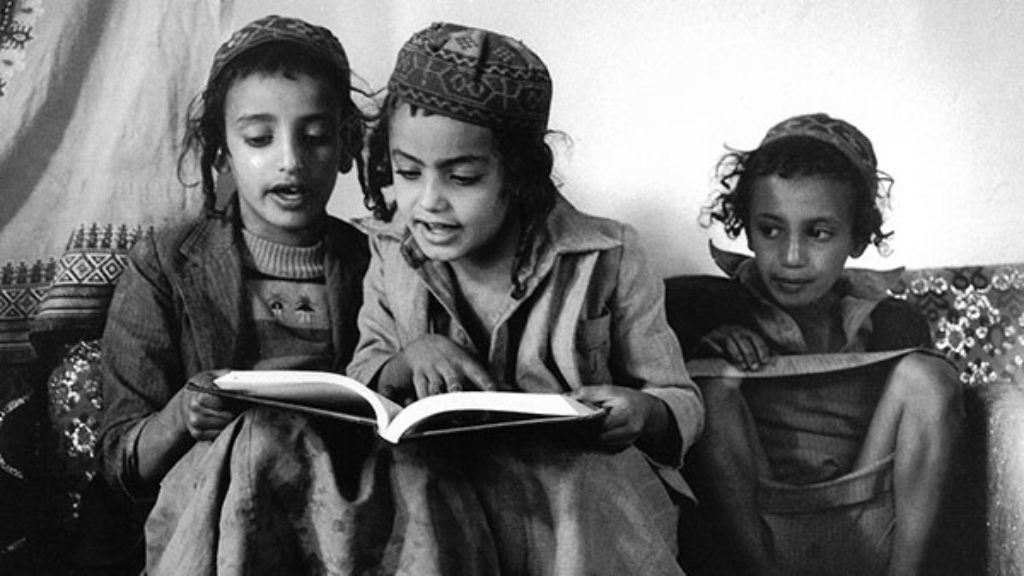

Visiting Yemen in the 1980s: A Photo Essay

"Sometimes one really does find that moment and the image seems to capture a person—this particular Jew, this particular way of life—but often one does not and feels the need to return, to try again." But in this case, there are no Jewish communities in Yemen to return to.

The Vanishing Point

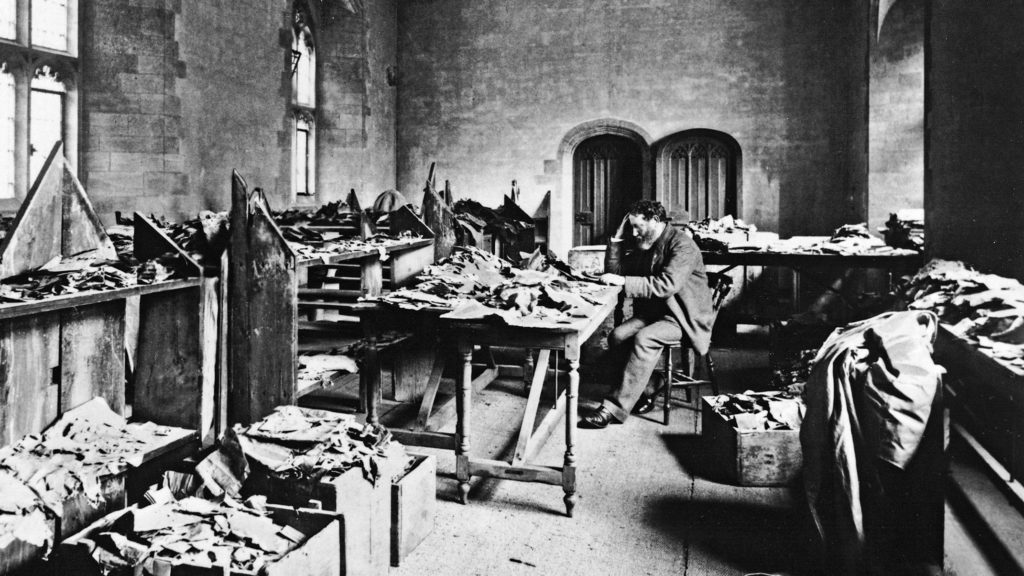

A new exhibit explores the vanished world and unseen photographs of Roman Vishniac.

Robert Capa’s Road to Jerusalem

By all accounts, his own not least, Robert Capa was a womanizer, a heavy drinker, and a compulsive gambler who consistently lost his shirt everywhere from poker games at the front lines to European casinos. He was also a gifted, prolific photographer.

Buried Treasure

Hundreds of thousands of Jewish manuscripts were redeemed from Egypt.

gershon hepner

PHYLACTERIAL

Performing in a manner that is phylacterial

commandments attributed to Moses

this Jewish poet, claiming to be more than willin'

binds on his arm and head his paired tefillin',

and rises----so at least his lovely wife supposes----

above the height of Luftmenschen, Hebrew Ariel,

sliding down most slippery, unspiritual, slopes,

not observing God despite these deoscopes.

Chaim Meiersdorf

Magnificant photographs. How were they done technically, what lighting was used. I cannot imagine that all these photos were done in daylight alone. It is the fantastic lighting that gives these photos the drama. First class work.