Robert Capa’s Road to Jerusalem

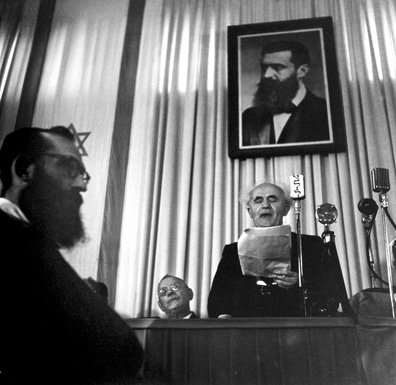

When David Ben-Gurion proclaimed the establishment of Israel on May 14, 1948, at the old Tel Aviv Museum of Art, Robert Capa was there. The world’s most famous photojournalist had covered the Spanish Civil War, the Allied conquest of North Africa and Italy, the invasion of Normandy, and the liberation of Paris. He had hobnobbed with Hemingway, romanced Ingrid Bergman, and toured Stalin’s Russia with John Steinbeck. Now he was in the Jewish homeland for the first time. His striking image of the state’s founding moment was recently shown in the postmodern wing of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, one of the 40-plus prints in Robert Capa: Photographer of Life (Tzalam shel ha-chayim in Hebrew).

The show’s English title is a fine pun, since Capa’s main venue was Life magazine, which in 1937 made his “Falling Soldier” picture an anti-fascist emblem of the Spanish Civil War. He was only 23. A decade later, Capa recalled in a radio interview how he had just reached out of a trench and clicked the shutter without looking and two months later discovered he was famous. In his thorough, unauthorized biography Blood and Champagne: The Life and Times of Robert Capa (2002), the British popular historian Alex Kershaw challenged that version, suggesting that Capa had staged soldiers in action during a lull in the fighting, attracting an actual enemy sniper. Wall text alongside the disputed photo at the Tel Aviv show remarked that, “It might be that the secret of the photograph’s magic—depicting that moment between life and death—and of the myth surrounding it, lies in the inability to reach a decisive answer.” The secret of the photograph might also be said of the photographer, who lived to the fullest, courted death, and created a heroic image of himself.

Here, then, is Robert Capa’s Ben-Gurion, standing before the microphones under a big photo of big-bearded Theodor Herzl and framed in the foreground by the profile of a similarly bearded Orthodox Jew, slightly out of focus, larger than either Herzl or the speaker. Israeli museum-goers were surely prone (as perhaps intended by the show’s skillful curator, Raz Samira) to read the image of the State’s inception as ironic, a prescient caution about religion and politics. I’m more inclined to read the picture as romantic, a hint of Capa’s bond with another Budapest-born Jewish artist, the secular playwright who embraced all Jews, bearded and otherwise, in a dream of return. What Capa had in mind is another question.

He preferred to keep things ambiguous, to make his life a legend. By all accounts, his own not least, he was a womanizer, a heavy drinker, and a compulsive gambler who consistently lost his shirt everywhere from poker games at the front lines to European casinos. Capa relished the persona of a Hungarian gypsy, and his exploits, including the wily acquisition of passports and whiskey, occupy much of his witty World War II memoir Slightly Out of Focus, published in 1947 and still in print. A New York Times reviewer extolled the pictures but carped that “nothing is duller to read about than another man’s hangover.” Capa had begun writing autobiographical sketches in Sun Valley, Idaho, in 1941, under the tutelage of Hemingway. “Writing the truth being obviously so difficult,” read Capa’s disclaimer on the flap of the first edition, “I have in the interest of it allowed myself to go sometimes slightly beyond and slightly this side of it.”

The title Slightly Out of Focus alludes to the fate of his D-Day pictures, shot under heavy fire, only to be ruined by a Life darkroom technician in London who accidently melted the film emulsions under deadline pressure. Life published the few salvageable negatives, including the iconic image of a lone soldier edging through the water toward Omaha Beach. “Immense excitement of moment made Photographer Capa move his camera and blur picture,” read the caption, shifting the blame. Capa resented the implication that he was less than steady under fire. “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough,” he used to say.

“Despite all his inventions and postures, Capa has, somewhere at his center, a reality,” wrote John Hersey in 1947, in his article “The Man Who Invented Himself,” a subtle review of the memoir for a short-lived literary magazine. Capa, wrote Hersey, “has the intuition of a gambler . . . His courage is partly his apprehension of the odds, and partly innate.” Eventually the odds caught up with him. He stepped on a mine in Vietnam on May 25, 1954 and became the first American journalist to die in Indochina. He was 40 years old.

Also at Capa’s center was his Jewish identity, be it ever so blurry. The son of middle-class dressmakers, he was born Endre Friedmann and fled fascist Hungary in 1931 for Berlin. A year later he published photographs of a fiery Leon Trotsky orating in Copenhagen. The most dramatic of these was in the Tel Aviv show, hanging alongside the Ben-Gurion picture and an image of Menachem Begin, his back to the camera, captivating a Tel Aviv crowd in 1950.

In 1933 he moved to Paris, called himself André, and met a young Polish-German Jewish emigrée named Gerta Pohorylle (she worked under the name Gerda Taro), who became the great love of his life. Together they took pictures and invented a mysterious, dashing photographer named Robert Capa who charged high prices for his brilliant work. “Money poured in,” wrote Hersey. “The association was happy, for Capa loved Gerda, Gerda loved Andrei, Andrei loved Capa, and Capa loved Capa.” Together, they covered the Civil War in Spain, where Gerda was killed in 1937.

Ten years later, Capa was plugging his book on the Hi! Jinx radio show in New York. Apart from being the only known recording of Capa’s Hungarian lilt—“a musical deformation of speech in all languages,” in the words of the writer Irwin Shaw, “dubbed ‘Capanese’ by his friends”—the interview sheds rare light on Capa’s Jewish identity. (Shaw himself was born Shamforoff in the Bronx in 1913, the same year as Capa.) Asked about the Hersey article and the origin of “Robert Capa,” he bristled:

A little bit it is John Hersey who invented the man who invented himself, or something like that. There are so many inventions going around about me . . . It’s kind of a corny kind of story, because sure enough, I had a name which was a little bit different from Bob Capa, that was long time ago in Paris, around 1934, 1935, and that real name of mine was not too good, you know . . . I couldn’t get assignment any more . . . I needed a new name very badly.

“What was your old name?” asked his interviewer, Jinx Falkenburg. “Oh,” replied Capa, “it’s very embarrassing to say something there, it began with Endre, and then it was Friedmann, the two of them hang together, and let’s discard it for the minute.”

Embarrassed or not, in his memoir’s opening chapter Capa describes himself as “born deeply covered by Jewish grandfathers on every side” and refers to his mother’s “big and loving Jewish heart.” Later on, he begins his chapter on D-Day with an odd Jewish anecdote:

Once a year, usually sometime in April, every self-respecting Jewish family celebrates Passover, the Jewish Thanksgiving . . . When dinner is irrevocably over, father loosens his belt and lights a five-cent cigar. At this crucial moment the youngest of the sons—I have been doing it for years—steps up and addresses his father in solemn Hebrew. He asks, “What makes this day different from all other days?” Then father, with great relish and gusto, tells the story of how, many thousands of years ago in Egypt, the angel of destruction passed over the firstborn sons of the Chosen People, and how, afterwards, General Moses led them across the Red Sea without getting their feet wet.

The Gentiles and Jews who crossed the English Channel on the sixth of June in the year 1944, landing with very wet feet on the beach in Normandy called “Easy Red,” ought to have—once a year, on that date, a Crossover day. Their children, after finishing a couple of cans of C-rations, would ask their father, “What makes this day different from all other days?”

Among other inaccuracies, Capa was not the youngest in his family—that was Cornell Capa, who adopted his brother’s invented surname and cultivated his legacy for more than half a century. All the same, it is interesting that Capa chose to frame the end of World War II in terms of Jewish memory and redemption.

In June 1945, a month after the Allies had accepted Germany’s surrender, Capa and Irwin Shaw were in the lobby of the Ritz Hotel in Paris when Ingrid Bergman walked into their lives. They wrote a note to the glamorous star of Casablanca and Gaslight, jointly inviting her to dinner. She was smitten with Capa, and they spent weeks together in Europe that summer before she returned to her husband in California. Capa went to Berlin to photograph the first postwar Rosh Hashanah for Life, and then she persuaded him to come to Hollywood. When he landed in town in December 1945, she was s tarring in Alfred Hitchcock’s anti-Nazi thriller Notorious, and Capa shot some stills on the set.

He got a job with a production company but quickly felt confined. “After more than a decade of war,” writes biographer Alex Kershaw, “Capa had started to exhibit many of the symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder: restlessness, heavy drinking, irritability, depression, survivor’s guilt, lack of direction and barely concealed nihilism.” He also unwisely played poker with John Huston, Howard Hawks, and Humphrey Bogart. He and Bergman continued their affair, and he even took her to meet his mother Julia. Bergman talked of divorcing her husband, a Swedish neurosurgeon, to marry Capa, but he could not commit, or settle down, and they finally parted in the spring of 1947.

“Nineteen forty-seven was a turning point in Capa’s life,” writes curator Cynthia Young in her handsome new volume, Capa in Color. “He founded Magnum, the photographers cooperative agency he had dreamed of since 1938, and traveled to the Soviet Union.” Capa and his partners in Magnum—notably Henri Cartier-Bresson and the Polish-Jewish David Seymour, known as “Chim”—now owned their own negatives, retaining copyright of their pictures. It was an act of radical defiance against Time-Life and its corporate culture.

Politically, Capa was a dedicated enemy of fascism, not a communist, though his work had appeared in a communist paper. He was keen to visit Russia, but had been turned down twice for a visa. Now he teamed up with John Steinbeck, respected by the Soviets for The Grapes of Wrath. Among the more intriguing photos in Capa in Color is a black-and-white snapshot of Capa and Steinbeck about to board a plane for the USSR. Steinbeck at age 45 is tall and dignified in a handsome hat, whereas Capa could pass for his kid brother, young and smug. Scores of pictures with helmet and dangling cigarette have typecast Capa as a Hollywood heart-throb, but in this shot, tripod jauntily perched on his shoulder, he seems more like Sammy Glick or Woody Allen’s protean Zelig.

Steinbeck wrote a book called A Russian Journal, with photographs by Capa. In a story for the British weekly Illustrated, Steinbeck dwelt on the omnipresent statues of Stalin, and Capa’s best pictures were a color shot of a young one-legged man among visitors to Red Square and a staggering black-and-white of the Children’s Dance Fountain amid the devastation of Stalingrad, a photo displayed in the Tel Aviv exhibit. The Illustrated story ran on May 1, 1948. One week later, on assignment for that same magazine, Capa landed in Tel Aviv.

© International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos.)

On June 21, 1948, the Hebrew dai- ly Al Ha-mishmar, the newspaper of the left-wing Hashomer Hatzair movement, published an interview with Capa by Eugen Kolb, a fellow Hungarian Jew who later became the director of the Tel Aviv Museum of Art. (In his authorized 1985 biography Richard Whelan wrote that Capa seemed to know every Hungarian in Tel Aviv, and “through them he kept himself and his fellow journalists well supplied with black-market food and liquor.”) “War interests me,” Capa told Kolb, “but I can’t stand the sight of blood . . . I never photographed a single corpse.” This was, of course, untrue: He had shot his famous pictures of the “last man to die” in World War II, in Leipzig only three years earlier. “I am a photographer of life,” he went on to declare, and after the war “my only wish was to finally be an unemployed war correspondent.”

It was one of his patented lines. He was quoted the same way in Illustrated in the text accompanying his gripping pictures of the Arab-Israeli war. But “once again,” the magazine continued, “the violence of war has caught up with Robert Capa.” In late May, Capa had gone to the Negev to cover the defense of Kibbutz Negba as hundreds of Egyptian shells flew overhead. On July 3, Illustrated ran a photo essay called “The Road to Jerusalem Was a Road of Death,” for which Capa had photographed soldiers in action. He also covered the laborious carving of the so-called Burma Road, a project commanded by the legendary American Colonel David “Mickey” Marcus to circumvent the siege of Jerusalem. His photo of a muscular Marcus working out on an exercise bar appeared in that issue, alongside another—taken shockingly soon thereafter—of Marcus’s funeral in Jerusalem. On June 11, Marcus was mistakenly killed near Abu Ghosh by an Israeli sentry.

Alex Kershaw calls Capa’s pictures of the War of Independence “the most lyrical and dynamic coverage of his career,” but they were virtually absent from the recent Tel Aviv show, apart from one shot of soldiers, possibly near Latrun. Many were displayed in an important earlier retrospective at the same museum in 1988, Robert Capa: Photographs from Israel, 1948–1950, curated by the Israeli Magnum photographer Micha Bar-Am. As the Hebrew poet Haim Gouri commented in the catalogue to that show:

The photographs of the Israeli war recall the pictures of the Spanish Civil War: sandbags against a wall, rifle slits, someone scampering across an area under fire, volunteer units, a soldier at rest reading a newspaper in the shade of a tree, the ubiquitous stocking cap, a meal eaten against a wall pitted with bullet holes.

When Capa spoke with Eugen Kolb of Al Ha-mishmar, a U.N. truce was in effect. “I appreciate Tel Aviv as a great achievement, and also the kibbutzim—but only a few days ago did I feel what Israel is,” said Capa. “It was when I traveled on the new road to Jerusalem, and the city appeared before my eyes.” That road was the high point of his stay, he said; he was with the road builders day and night, and photographed every stage of the labor. “The picture dearest to me is an old stone cutter from Jerusalem, with beard and sidelocks, working to clear the road.”

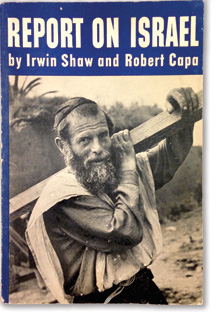

No image fitting that description hung in the Tel Aviv show, but it appears in Report on Israel, the book that Capa and Irwin Shaw published in 1950. The caption reads “Stonecutters from besieged Jerusalem working on that Middle Eastern necessity—a detour,” but under its sun-baked banality is the story of refugees carving a homeland. It’s not a great photograph, but its triangulated composition rhymes with the picture of Ben-Gurion and Herzl. The cover choice for that book shows how Capa’s cynicism melted away in Israel. Here again we find a religious Jew with a beard. The man eyes the photographer warmly, with only the faintest trace of suspicion, or amusement. He is a strong man, a builder, an “old-new” Jew wearing both kippa and tzitzit, yet he looks, at first glance, like he’s carrying a cross.

On June 21, the same day the Capa interview ran in Al Ha-mishmar, the ship Altalena, carrying weapons for the Irgun, grounded itself at midnight off a Tel Aviv beach. The following afternoon, the confrontation between the Haganah—now known as the Israeli army—and the Irgun or Etzel, the right-wing militia commanded by Menachem Begin, reached its bloody climax. Ben-Gurion had demanded that the Irgun surrender its weapons and disband in order to create a single fighting force for the new state. Although Begin wanted to avoid violence, he could not accept Ben-Gurion’s terms. Ben-Gurion ordered that the ship be shelled. The Altalena caught fire but luckily did not explode. Shooting broke out on the beach. And there to capture the fratricidal tragedy was the ubiquitous Robert Capa.

Capa sold his Altalena pictures to Life, which on July 12 ran two pages with the headline “JEW FIGHTS JEW IN THE HOLY LAND/Photographer records ill-fated Irgun landing.” The Irgun, opined Life, “chose a singular time and place” for its action, in the midst of a truce and “under the noses of U.N. observers sweating it out” at a beachfront hotel. “Meanwhile Photographer Robert Capa took up his own position on the balcony of the hotel and photographed this remarkable blow-by-blow account.” There are five small photos as the battle is joined, and one big, climactic shot: “CREWMEN AND VOLUNTEERS TAKE TO THE WATER WHILE THEIR ILLEGAL ARMS AND AMMUNITION—REPORTEDLY ENOUGH TO SUPPLY 4,000 TROOPS—GO UP IN SMOKE.” That photograph is very similar to the one that was displayed at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art.

Magnum Photos.)

A color picture of the burning Altalena appears in Capa in Color. It is taken from the same angle, with a giant trumpet of smoke, but there are no Irgun men in the water or rescuers on paddleboards. The shrubbery casts long shadows, but there was enough light for a sharp color exposure, perhaps with the use of a tripod. The beachfront seems to have been cleared of spectators. A few boys ride away from the beach on bikes, apparently turned away by guards. It is evidently the quiet afternoon after the battle.

Capa being Capa, there’s more to the story. The biographer Richard Whelan wrote that Capa “moved forward on the beach, to photograph people jumping off the blazing ship,” with bullets “whizzing around him from all directions.”

When Capa was close enough to get his pictures, he assumed a half-crouching stance with his legs well apart. All of a sudden, a bullet grazed the inside of his thigh. For one sickening moment of blind panic, before he could locate the area of pain precisely, he feared that the bullet had unsexed him. When he told the story later, he claimed that, despite the danger around him and the encumbrance of the cameras around his neck, he undid his belt on the spot and pulled down his pants, all the while spinning like a dervish from fear and pain. Everything was intact; the bullet had only grazed his thigh, leaving a bad bruise but not even breaking the skin. He told his friends that, taking this terrifyingly close call as a warning, he ran back to his hotel and left Israel on the next plane for Paris.

If he was thus traumatized, when and how did Capa take the sharply focused color picture of the ship burning, with no men left in the water? And if he’d really been on the beach during the confrontation, why didn’t he take any pictures before being grazed by the bullet? Why are all his published shots of the Altalena story taken from a high angle, the balcony? His other war pictures from Israel are closer, better. Capa may not have been “close enough” this time, but he was well placed to spin an entertaining yarn.

What to make of it? On one level, it’s Hemingway with a happy ending: Jake Barnes dodges the wound. Or, perhaps it was a symptom of survivor guilt for a career built on death: the “falling soldier” and Gerda in Spain, the carnage of World War II, the slain Jews of Budapest, and now, only 11 days ago, Capa’s new friend Mickey Marcus. Or dare we suggest a baptism by fire into a fellowship of Zionism, a kind of farcical, figurative brit milah? In an affectionate tribute to Capa, published in Vogue in 1982, Irwin Shaw remembers him saying, “That would be the final insult—being killed by the Jews!”

Magnum Photos.)

After the Altalena, Capa traveled to Poland with Theodore H. White, then serving as a European correspondent for the Overseas News Agency. White had grown up Orthodox in Boston and done his best to submerge his Jewish roots. In his 1978 memoir In Search of History: A Personal Adventure, he confided that he cried amidst the remains of the Warsaw Ghetto, but that at Auschwitz he “had neither tears nor words.” Capa’s shot of the ghetto—a lone church looming over a vast field of rubble—was one of the strongest pictures from the Tel Aviv show. White doesn’t discuss Capa in his memoir, so all we can do is imagine these two conflicted Jewish journalists on their long drive away from the camp, arguing about Zionism, which White had abandoned as a student at Harvard. “I was never a Zionist,” Capa had told Al Ha-mishmar, “and I’m not one now either, but in any event I have changed my view about Israel: I am now convinced that for most of the world’s Jews there is no other solution except Israel. And those who deny this rely on reasons that are immoral. Yes, I am a friend of this land and its people.”

Following Poland, Capa returned to his native Budapest for six weeks. “Looking down on the burned-out row of hotels and the ruined bridges,” Capa wrote in the travel magazine Holiday, “Budapest appeared like a beautiful woman with her teeth knocked out.” His article, reprinted in Capa in Color, included a long conversation with a boyhood friend named Sandor, a furrier. “As only one of twenty of Hungary’s Jews survived the war,” wrote Capa, “I was surprised to see that his name was still above the shop, and even more surprised to find him alive.” Sandor described his wartime travails in Russia and his difficult existence in communist Budapest. “I left his shop feeling sorry for both of us,” wrote Capa. “He was my age and he made me feel suddenly very old.”

He also may have made Capa feel homesick for Israel. At any rate, when Capa learned that Irwin Shaw was headed for Tel Aviv in the spring of 1949 on assignment for The New Yorker, he suggested they team up and get a book out of it. Gifted and prolific, Shaw had a play on Broadway, Bury the Dead, when he was 23. In 1946 and 1947 he published short stories in Collier’s and The New Yorker about a Jewish survivor in Tel Aviv and a British policeman in Haifa. His best-selling World War II novel The Young Lions (1948) focused on anti-Semitism in the American army. Shaw, too, was intrigued by the ingathering of the exiles in the new Jewish state, but, perhaps because he was born in the Bronx not Budapest, he doesn’t seem to have taken the story as personally as Capa.

They arrived in time to cover Israel’s first birthday. In Shaw’s “Letter from Tel Aviv,” published in The New Yorker on May 28, 1949 and retitled “Independence Day” as the first chapter of Report on Israel, Shaw described denizens of Tel Aviv sitting on beach chairs on the fifth of Iyar, watching “their children swim out through the pretty green water to the rusting hulk of the LST Altalena . . . making a plaything out of a tragic monument.” The 1949 photo of the ship and holiday crowd, shot this time from beach level, takes up a double spread at the center of the book, its largest picture, the heavy heart of Capa’s Report on Israel.

Shaw found Tel Aviv “unbeautiful” and noted that in Israel, “as in Italy, the men, both young and old, are more attractive than the women.” His text is larded with facile generalizations, some amusingly outmoded today, others less so:

Little hard liquor is drunk, and a drunkard is almost certain to be a visiting American. The food suffers from the residents’ general impatience with the gentler aspects of civilized life.

The driving is ferocious . . . As one visitor said, after a drive from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem, “No wonder they won the war. They will risk their lives over as little a thing as reaching a café thirty seconds ahead of the next man.”

According to one’s sympathies, the people are either magnificently self-confident or unpleasantly arrogant about their abilities.

Capa, meanwhile, was busily taking evocative pictures of Israelis, sabras and immigrants, young and old, religious and secular. “Everywhere, the land is alive,” wrote Capa in an inspiring photo-essay called “Israel Reborn” that ran in Look. “The people are building again on the ruins left by the recent years of fighting. Behind them they have many new legends to add to the Biblical legends of old.” Capa’s account was free of irreverence, his voice a far cry from the ironic tone of Slightly Out of Focus. “Five of the six settlements started each week are in the Negev,” he wrote, where “the real future of Israel” lies. New immigrants are pictured boarding a truck for resettlement in “an abandoned Arab village, where they must first rebuild the houses.” Whereas Shaw in The New Yorker had described an Israeli who “regards American Jewry rather disdainfully as an inexhaustibly rich mine of dollars,” Capa respectfully reported that, “the United Jewish Appeal finances the basic program of receiving, feeding, and sheltering new immigrants into Israel.”

Indeed, Capa’s third trip to Israel, in 1950, was for the UJA, which asked him to direct a short fund-raising film about immigrant absorption. He was, reportedly, a less than professional filmmaker, unnerving UJA chairman and former Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau during a shoot at a moshav named in his honor. On that same trip, however, Capa took some of his most expressive pictures of Israel. A dramatic shot of housing construction near Beersheva, reproduced in Capa in Color, is one of the many Capa pictures celebrating the rapid development of the country. An elegantly composed black-and-white of Yemenite olim, captioned by Life as “Tribesmen from Arabia,” was among the half-dozen images from the ma’abarot, immigrant transit camps, that, for me, were the most memorable pictures in the Tel Aviv show.

The chapter on Jerusalem in Report on Israel originated not in The New Yorker, but in Illustrated magazine. “Jerusalem is a city of endless contention,” wrote Shaw, “and within its walls there have been few arguments that have not been settled finally by bloodshed.” The Old City, in 1949, was off limits to Capa and Shaw, of course, but Shaw recalled his 1943 visit to the “Wailing Wall” and how the old men and women touched it “inch by inch, first with their fingertips, then with their lips, giving a strange appearance of idolatry to their whispered prayers.” Shaw’s essay, republished in Capa in Color, still rings true, even if its conclusion is clichéd: “Peace, the carved stone letters say on the monuments; peace, chant the worshippers. But if men can have peace in Jerusalem, men can have peace anywhere on the planet.”

Capa ended his Look essay on a similar note. After describing a visit to President Chaim Weizmann at his home in Rehovot, Capa tells of an aged rabbi from Yemen, living nearby in an abandoned Arab house:

He scarcely lifted his face from his dog-eared Talmud as I talked to him. When I left, saying good-by with the traditional “Shalom,” the old rabbi looked up. He murmured: “Shalom, shalom, ve-eyn Shalom! Peace, peace, but there is no peace!”

An old man fitting that description turns up not in Look but in the Shaw-Capa book, with laughing eyes barely open and a philosophical grin.

Look ran a full-page picture of the dapper Weizmann and his young grandson seated on a patio. Weizmann’s eyes are closed and the barefoot boy wears an innocent smile. Weizmann “lives quietly,” reads Capa’s caption, “remembering a 60-year fight for a free Israel”—which, in fact, is just what it looks like. John Steinbeck remembered his friend as having been able to “photograph thought.” Do we ascribe a unique magic to Capa’s work because of his bravery, fabled charm, and tragic early death, our conveniently constructed narrative of Jewish return? His Israel pictures are, arguably, the strongest and most heartfelt of his career, but are they better than that of others? In reply, I would single out a picture from the 1988 Tel Aviv Museum catalogue of an immigrant family arriving by ship, viewing Israel for the first time. It’s a close shot, not merely because of Capa’s physical proximity to these Jews but because he might have been one of them. One is tempted to call it “Friedmann Comes Home.”

“Settling in Israel himself was increasingly on Capa’s mind,” wrote Richard Whelan, providing, as usual, no source for this intriguing claim. Be that as it may, Capa spent most of the early 1950s based in Paris. He hung out at the Longchamps racetrack with famous friends and shot colorful stories for Holiday about the good life in Rome, Paris, and the French resorts. (A black-and-white print of revelers at Biarritz was the only post-Israel picture at the Tel Aviv Museum show.) He skied with Shaw at Klosters, a Swiss village popular with Hollywood celebrities. “The last time I saw him,” Shaw wrote in 1982, “was at the railroad station of Klosters, where he was serenaded by the town band as he climbed aboard the train with a bottle of champagne and someone else’s wife.” Capa was on his way to a job in Japan, where he received a cable from Life, asking if he could replace a photographer in Vietnam whose mother had fallen ill. His pictures of French soldiers crossing a field are the last images in Capa in Color.

The magazine eulogized him as “the first LIFE war photographer ever killed in line of duty.” Hemingway cabled from Madrid: “He was so much alive that it is a hard long day to think of him as dead.” Lacking any formal Jewish affiliations, Capa was buried in a Quaker cemetery in northern Westchester County, New York. His gravestone gives the date of his birth in Budapest and of his death in Vietnam, and one more word, in Hebrew, “Shalom.”

Suggested Reading

Jews, Revolutionism, and Doublethink

Even in the Gulag, it was difficult to give up the belief in the Revolution. Take Evgenia Ginzburg, for example . . .

Montefiore and the Politics of Emancipation

More than a shtadlan.

“He Called Me Jim”

In his autobiography, James Atlas explores how and why he spent his professional life living with and overshadowed by complex, overweening literary giants.

A Dashing Medievalist

Ernst Katorowicz had great courage and old-world personal charm—his Berkeley students were mesmerized by him.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In