Depths of Devotion

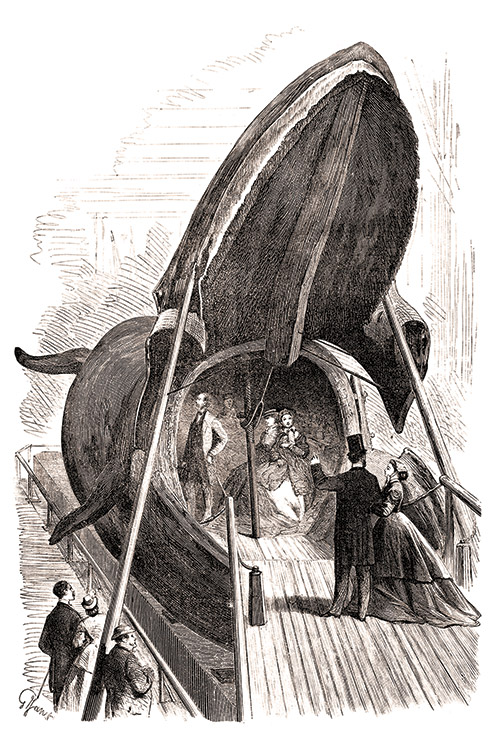

In 1865, a blue-whale calf washed ashore near Näset, Sweden. After its death, its skin was preserved with arsenic and mercury chloride, and its body was reconstructed using copper furniture studs. When the whale was displayed at the Museum of Natural History in Gothenburg, its mouth was propped open as if ready to swallow visitors. “Its interior was decked out as a lounge, with wooden benches, red carpet, and a ceiling lined in blue muslin decorated with little gold stars,” writes Rebecca Giggs in her recent book, Fathoms: The World in the Whale. On special occasions, guests were served dinner and coffee inside the 52-foot-long animal. American tourists liked to have their photos taken in the belly of the preserved beast, praying, as Jonah had done in the Bible. That is until the 1930s, “when two lovers were caught inside the whale, having consummated their passions in its esophagus.” The whale’s mouth was then closed.

Intrepid tourists are far from the only ones who have been fascinated by the setting of Jonah’s prayer. Chapter 2 of the book of Jonah tells us only that “The Lord provided a huge fish to swallow Jonah,” where he remained “for three days and three nights,” leaving quite a bit to the reader’s imagination. In fact, imagining Jonah’s uncomfortable predicament as he “called out to the Lord” from the depths turns out to have been surprisingly common among literary modernists.

To Herman Melville’s Father Mapple, Jonah’s yarn, “one of the smallest strands in the mighty cable of the Scriptures,” reaches its apex with Jonah’s prayer from the abyss. “What depths of the soul does Jonah’s deep sealine sound! What a pregnant lesson to us is the prophet! What a noble thing is that canticle in the fish’s belly!” the preacher proclaims. Later in Moby-Dick, Jonah is “historically regarded” by way of the real-life religious scholar Bishop John Jebb, who imagined the unfortunate prophet not as “tombed” in the whale’s belly but rather temporarily lodged, and having prayed from, somewhere in its mouth. After all, “the Right Whale’s mouth would accommodate a couple of whist-tables, and comfortably seat all the players. Possibly, too, Jonah might have ensconced himself in a hollow tooth; but, on second thoughts, the Right Whale is toothless.”

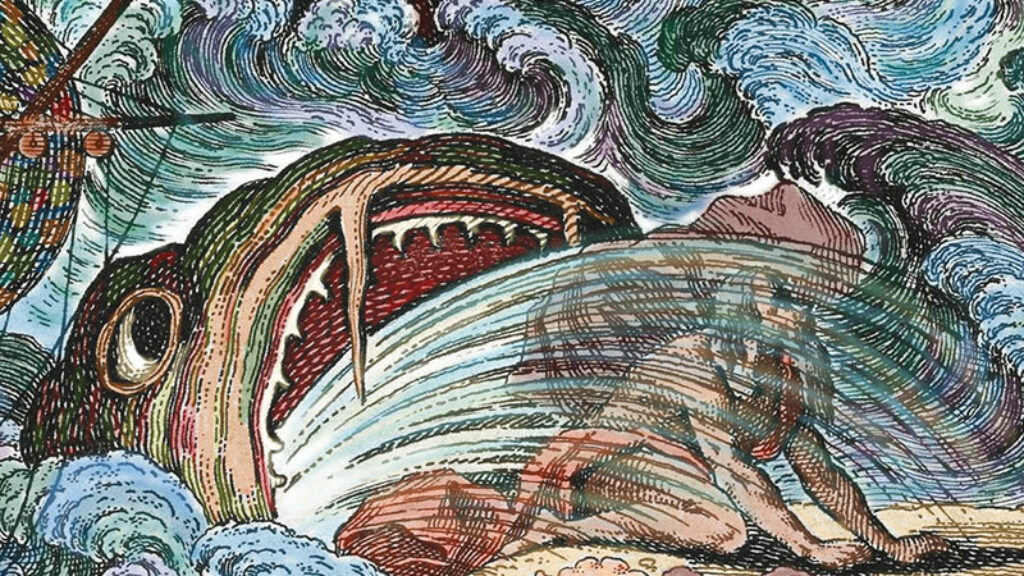

Aldous Huxley, in a 1920 poem, depicted the scene even more graphically. Picturing the prophet “seated upon the convex mound of one vast kidney,” he describes the gruesome hollow vault of the great fish’s mouth through which Jonah’s prayer resounds, causing the fish to “spout music as he swims”:

Many a pendulous stalactite

Of naked mucus, whorls and wreaths

And huge festoons of mottled tripes

And smaller palpitating pipes

Through which a yeasty liquor seethes.

It was the implausibility of a giant sea creature burping up lines like “You cast me into the depths, / Into the heart of the sea . . . Would I ever gaze again / Upon Your holy Temple?” (Jonah 2:4–5) from an interior passenger that sank any presumption of the Bible’s historicity for Clarence Darrow. “But when you read that Jonah swallowed the whale–or that the whale swallowed Jonah–excuse me please,” he snarked at William Jennings Bryan during the Scopes Trial, “how do you literally interpret that?” To which Bryan replied,

When I read that a big fish swallowed Jonah–it does not say whale. . . . That is my recollection of it. A big fish, and I believe it, and I believe in a God who can make a whale and can make a man and make both what He pleases.

In George Orwell’s review of Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer, Jonah’s predicament becomes an allegory for authors like Miller who avoid the political waves buffeting their contemporaries. “There you are,” Orwell writes, “in the dark, cushioned space that exactly fits you, with yards of blubber between yourself and reality, able to keep up an attitude of the completest indifference, no matter what happens.” According to Orwell, such writers rob reality of its terrors by submitting to them. Of Miller, he writes, “all his best and most characteristic passages are written from the angle of Jonah, a willing Jonah. . . . He has performed the essential Jonah act of allowing himself to be swallowed, remaining passive, accepting.” Decades later, Salman Rushdie argued that our own times are “whaleless,” absent of “quiet corners, there can be no easy escapes from history, from hullabaloo, from terrible unquiet fuss.”

The ancient Rabbis, too, couldn’t help but imagine what it must have been like for Jonah to offer his devotion from the depths, but, unlike Melville and Huxley, they did not picture what it would be like to be caught in the viscous confines of a fish. Neither did they think, as Orwell did, of Jonah’s confinement as an allegory about the individual and society. Rather, the midrashic work Pirkei d’Rabbi Eliezer describes Jonah entering the fish’s mouth “just as a man enters the great synagogue.”

And he stood inside. The two eye-windows were like windows of glass giving light to Jonah. Rabbi Meir said: One pearl was suspended in the belly of the fish and it gave illumination to Jonah, like the sun which shines with its might at noon; and it showed to Jonah all that was in the sea and in the depths, as it is said “Light is sown for the righteous” [Psalms 97:11].

In this rabbinic rendering, the belly of the fish is a shul in which Jonah prays for forgiveness just as the congregation does on Yom Kippur when the book of Jonah is read as evening descends and light—one hopes—is once again sown for the righteous.

Suggested Reading

Repentance and Desire

Mizrachi identifies the heightened energy she senses in the streets of Israel during the days between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. She renames the period between Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur known as the Ten Days of Repentance, “Aseret Yemei Teshuva,” as the “Aseret Yemei Teshuka,” or “Ten Days of Desire,” a time when the yearning for a return to God and Torah reaches a primal, visceral level.

Jonah: The Sequels

“And shall I not care about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than one hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not yet know their right hand from their left, and many beasts as well?”

Sitting with Shylock on Yom Kippur

The poet Heinrich Heine imagined the merchant of Venice attending Neilah, the final service of Yom Kippur, but I find him earlier in the day, at Mincha, and we are listening together to the story of another Jew among Gentiles, bitter at being compelled to show mercy.

At the Threshold of Forgiveness: A Study of Law and Narrative in the Talmud

In this season of repentance, it is not only the laws of the rabbis, but their stories as well, that teach us how—and how not—to forgive.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In