The Protocols of Neoliberalism

The problem with trying to capture the Zeitgeist in a novel is that it’s always on the move. You could say about it what the watchmen on the roof of Elsinore say about the ghost of Hamlet’s father: “’Tis here! ’Tis here! ’Tis gone.” World Shadow, a brilliantly ambitious book by the Israeli novelist Nir Baram, was published in Hebrew just nine years ago, at a time when neoliberalism was enemy number one for idealistic leftists. But the English translation by Jessica Cohen is appearing in a different world, and it’s hard to summon up the same indignation against the sins of liberal democracy now that it is fighting for survival against much worse alternatives. In 2022 World Shadow reads like a time capsule, in which the passions and illusions of the day before yesterday are fascinatingly preserved.

When Baram’s novel was published in Europe, it earned comparisons to Don DeLillo’s 1997 classic Underworld, another book that aimed to sum up the collective paranoia of a generation. But the writer repeatedly named in World Shadow is Balzac, and Baram’s method has more in common with the great French realist than the American postmodernist. What interests him above all is how people act and talk in different social niches, especially ones that most of us will never get to enter. Balzac acts as a kind of spy in nineteenth-century Paris, infiltrating the worlds of politics, journalism, and high-class prostitution. In doing so he suggests that each of these worlds functions as a conspiracy, speaking its own language and pursuing its own goals under society’s nose.

Baram makes this idea literal, introducing us to three different conspiracies that end up intersecting explosively. The first is a small anarchist group in London, a random assortment of outcasts and dropouts who catalyze a global movement by calling for one billion people to go on strike on the same day, November 11. (The year isn’t specified, but the novel clearly takes place in the then-present, the 2010s.) They gain attention for their message with provocative stunts aimed at cultural institutions—running amok in the British Library, burning down an art gallery—and soon Facebook is full of “11/11” groups doing similar things around the world. As the plotters’ ambitions become more serious and violent, under the leadership of the charismatic Julian, they form a clandestine commune in an Irish village and prepare to strike.

This cell has no formal name; we learn about them in a narrative by one of the members, who simply refers to “us.” “You could say a lot of us believed in what are often called conspiracy theories, which might seem peculiar to people who read the papers and watch Sky and the BBC and all that rubbish,” the narrator fumes. But Baram effectively imagines them as a hybrid of Occupy Wall Street and al-Qaeda. Like the young people who occupied Zuccotti Park in Lower Manhattan, they are righteously indignant at a system that distributes wealth and power so unequally. Like the terrorists who carried out the 9/11 attacks, they are determined to infiltrate that system to bring it down.

This is the type of conspiracy that governments and police are created to combat. More insidious, Baram suggests, are the conspiracies that create governments in the first place. That is the business of Mayu, Steinback and Vanderslice (MSV), a DC political consultancy that boasts on its website of having “managed campaigns on every continent and worked with the world’s most influential parties and leaders.” The key to their influence, and to the political thesis of World Shadow, is that MSV is a proudly liberal shop. Its seventy-year-old founder, Jordan Steinback, boasts about his Democratic credentials: “I had the honor of being a pollster for McGovern in ’72, and to this day I maintain that McGovern was the most consistent, value-driven politician I have ever known,” he declares.

Liberal rhetoric, however, is a smoke screen for MSV’s actual work, which is helping corrupt candidates win elections in Third World countries. In a section composed wholly of emails between different employees at the company, Baram shows how they use the dark arts of modern campaigning to elect a Bolivian president who is in the pocket of mining corporations and the International Monetary Fund. When one consultant, Daniel Kay, finally gets sick of compromising his ideals, he goes rogue and threatens to expose MSV’s deepest secrets, such as its links to an arms dealer who sold weapons to the Hutus during the Rwandan genocide.

The arms in question included Israeli-made Galils, which connect MSV to the third story Baram has to tell in World Shadow. Here the protagonist is Gavriel Mansour, a young Israeli on the make in the 1990s, who has the good luck to impress Michael Brockman, an American Jewish hedge fund tycoon. Brockman charges him with setting up a foundation in Israel to promote peace and democracy, and soon Gavriel is funneling millions into Birthright-style summer programs and academic conferences.

He soon figures out, however, that Brockman’s philanthropy is merely a loss leader for his business interests. Making connections in government circles helps him lobby on issues that really matter, such as lowering tariffs on American imports. Gavriel has effectively been recruited into a conspiracy too, and he learns that a surprisingly large sector of Israeli society is run along the same lines. Everywhere he looks, well-connected fixers are steering business and government for their own enrichment—even if it involves selling weapons to murderous warlords.

In geopolitical terms, the Israel plot in World Shadow appears petty by contrast with the other two. The anarchists in London aim to overthrow capitalism, and MSV is making and breaking governments on several continents, while all that’s at stake in Gavriel’s story is a few million dollars and one man’s integrity.

That very disproportion, however, is a sign that Gavriel’s story is the one Baram needed to tell most. As an Israeli born in 1976, his political consciousness was formed in exactly the period covered by Gavriel’s rise and fall, from the high hopes of Oslo in 1993 to the financial crisis of 2008. For Israelis, “the nineties were intoxicating,” Baram writes. “It was an era of big ideas, and the people who came up with them were not interested in money alone: they aspired to redefine the country’s direction and its place in the world.”

In these years Israel embarked on two profound transformations: from the socialism of its founders to free-market capitalism, and from enmity with the Palestinians to cooperation. The fact that the first transformation was carried through while the second foundered is the basis of Baram’s grievance against neoliberalism. He expanded on this generational experience in “After Oslo,” an essay published in the Jewish Quarterly last year that makes a useful companion piece to World Shadow. In conversations with several old friends and schoolmates, he shows how the failure of the peace process essentially destroyed leftism and the Labor Party as viable forces in Israeli politics.

For Baram this development hit close to home. His grandfather had been a cabinet minister in Yitzhak Rabin’s first government in the mid-1970s, and his father was a minister in Rabin’s second government in the 1990s. As with the Temple, there would be no third, leaving the novelist to mourn for what might have been.

World Shadow uses the Israeli experience as a microcosm for understanding the West as a whole during the same period. Bill Clinton and Tony Blair, too, claimed to care about peace and justice, but when push came to shove, they were more interested in making money. Worse, from Baram’s perspective, they convinced themselves that making money was a progressive act—that opening borders and privatizing state assets made the world better for everyone. A case can be made that they were right, but to critics of neoliberalism in the early 2000s, this kind of hypocrisy was more obnoxious than outright authoritarianism—a political phenomenon of which they had no experience, yet.

In Baram’s novel, MSV are the masters of the neoliberal order and the London anarchists its victims, while Gavriel is merely a go-between. Whatever power he possesses is entirely dependent on Brockman. But when the latter’s hedge fund goes belly up in 2008, it is Gavriel who gets blamed for the ensuing Madoff-style ruin of Israeli and Jewish nonprofits, turning him into a national villain.

In the last section of the novel, a gang of young Israelis kidnap Gavriel and force him to confess his past misdeeds on video, inspired by the global 11/11 movement, which has made such “Personal Accountability” sessions their trademark. “You’re a classic example of the people we’re protesting against,” one of the activists tells him.

World Shadow draws its energy from the resentment of the young against their well-meaning elders and parents, who claimed to be virtuous but turned out to be only human. By comparison with the political forces at work today, however, only human is starting to look pretty good.

Suggested Reading

Equine Ambles into a Watering Hole: An Interview with Jessica Cohen

An interview with Jessica Cohen—winner of the 2017 Man-Booker International prize for her translation of David Grossman’s Horse Walks Into a Bar—on translating Hebrew literature and jokes.

Perish the Thought

Bruno Chaouat dares to ask whether, given the moral autism of so many of Theory’s luminaries when facing the basic political questions of our time, his own romance with it has been a similar waste.

Sundowning

In Morningstar Heights, Joshua Henkin tells his story simply and directly, with a narrative economy that conceals much close observation and human understanding. These have always been the strengths of his work, though they are not the qualities best rewarded in contemporary American fiction.

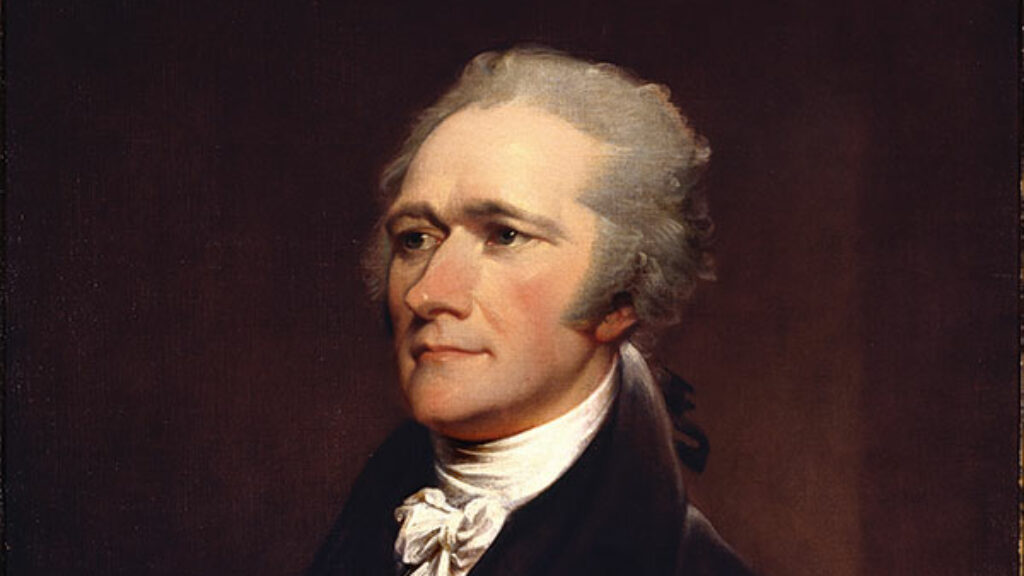

Ten Duel Commandments

Alexander Hamilton was, as the song goes, a “bastard, orphan, son of a whore and a Scotsman.” Was he also a Jew? Well, he did go to Hebrew School in the West Indies, but ...

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In