Cultural Life in the Vilna Ghetto

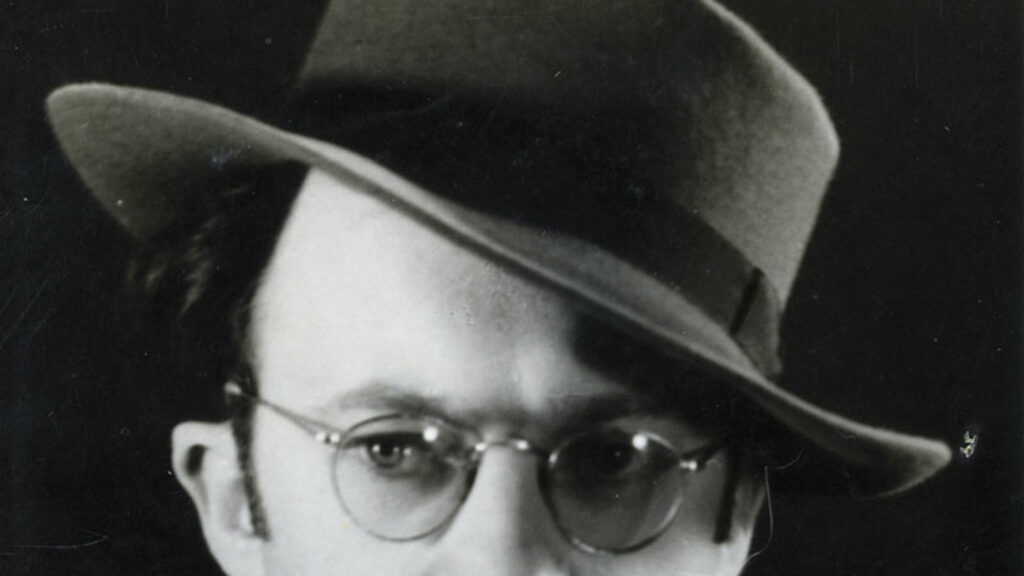

Among the great Yiddish poet Abraham Sutzkever’s earliest lyrics were those published in a songbook of the Vilna Yiddishist scouting movement Bin (Bee), to which he swore an oath to serve Yiddish culture. Before he turned thirty, Sutzkever would be called upon to fulfill his teenage commitment in ways neither he nor his readers could have ever imagined. For more than two years, from the German occupation of Vilna in late June 1941 through September 1943, he witnessed and shared in the horrifying fate of his community, including the murder of his mother and newborn son, but he did not fall silent. Years later he would reflect: “I wrote more in the Vilna Ghetto than I did the rest of my life. How? With what strength? It’s incomprehensible.” Nor was he alone. As he would write just after the war, “Cultural life in the Vilna Ghetto began the moment the ghetto was established.”

If it was once assumed that there was no purpose to creative life for one condemned to death or abandoned on an island, our lived experience taught us the exact opposite. Whether a creative person resides in a modern hotel or in a desert amid sand and jackals, whether he admires the sunset by the seashore or stands by the edge of a grave he has been forced to dig himself—the spirit of creativity does not abandon him.

Sutzkever did not only contribute to the Vilna Ghetto’s cultural life with his verse. He mentored its youth group, helped organize the ghetto theatre, and, of course, read his poetry at literary gatherings. He also worked heroically alongside others as a member of the so-called Paper Brigade, those slave laborers whom the Germans appointed to sort materials from various Jewish libraries who smuggled and hid as many of the most valuable literary treasures as they could.

On September 12, 1943, only days before the Nazi liquidation of the Vilna Ghetto, Sutzkever and his wife escaped on foot with a group of fellow partisans. They spent six months in the forest until the Soviet Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee (JAFC) learned that the Sutzkevers were living at a partisan camp and arranged for his rescue. On April 2, 1944, he was invited to address a plenum of the JAFC in Moscow, where he was the only speaker who did not invoke Stalin’s name.

Soon after he arrived in Moscow, he was asked to write about the Vilna Ghetto for The Black Book project by Ilya Ehrenburg and Vasily Grossman. He already had drafted a significant portion of his chronicle when he rushed back to Vilna in July 1944 after the Red Army wrestled it from the Nazis—and encountered a Jewish ghost town. For the next several months, he feverishly searched for materials that he and his colleagues had hidden during the war while interviewing the few survivors there. He also added a new section to his chronicle describing in stark detail Nazi efforts to conceal their crimes. After he returned to Moscow in September 1944 and finished editing his chronicle, he turned his attention to his central focus as a poet, editing his wartime lyrics and drafting early sections of what would later appear as a book-length epic inspired by those Jews who lived in the sewers beneath Vilna.

When publication of The Black Book was halted due to pressure from the Communist authorities, he published his account of the Vilna Ghetto in separate book form. It appeared in early 1946 in Moscow and Paris in slightly different versions. The excerpts below are taken from my new translation of this work, together with Sutzkever’s diary notes from his dramatic testimony at the 1946 Nuremberg trials and three essays about Soviet Jewish cultural figures he met in Moscow, which help the reader understand what it meant to write his memoir of the Vilna Ghetto under the watchful eye of a Soviet censor.

In these selections, Sutzkever sketches the ghetto’s intense cultural life in the form of theatre, music, art, literature, and education. Sutzkever’s prose shows a deep respect for his fellow Jews and artists who made their work and art a central part of their resistance to their Nazi tormentors. Here, as elsewhere, Sutzkever wrote not only to honor the dead but to craft a usable past for future generations.

__________________________

Theatre

The day after my mother was murdered, the young director Viskind came to pay me his condolences. He invited me to a meeting of Yiddish actors. They wanted to establish a theatre. I looked at him, astonished:

“A theatre in the ghetto?”

“Yes,” Viskind confirmed. “We must be true to ourselves and resist the enemy even with this weapon. We must not surrender under any circumstance. Theatre was also performed in the ghettos during the Middle Ages. The origins of Yiddish theatre are there. Let us, too, create a theatre to delight and embolden the ghetto. It might even be the vanguard of a new Yiddish theatre in a free world.”

I left. Viskind’s faith soothed my sadness. At Strashun Street 7, in the frigid little attic belonging to the actor Blyakher, I met with the remaining actors in the ghetto. All of them were in favour of establishing a theatre. I agreed with them and accepted the position of literary director of the planned theatre.

We got to work on the first performance. It was a challenge to choose appropriate material. With what words could we appear before audiences and avoid dishonoring their anguish? How could we temporarily cloud the vision of mass graves before their eyes? And how could we awaken ghetto residents to the heroism of Jewish history, to appreciate beauty, and to continue to believe in the future?

Art Exhibit

In March 1943 an art exhibit was held in the foyer of the ghetto theatre. The exhibited works included several colourful landscapes by Rokhl Sutzkever, Yankev Sher’s graphic art “From the Old Ghetto,” miniature wood carvings by Daykhes, Notes, and Vultz, sketches by the architect Mme Rom, and works by nine-year-old Samuel Bak.

In honor of Yehoash, the Yiddish poet and translator of the Hebrew Bible, the literary circle organized a colourful exhibit at the youth club. Over the course of half a year, I smuggled into the ghetto from local libraries and museums all the works, pictures, letters, and manuscripts by this writer, in addition to original letters to Yehoash by writers of his generation: Peretz, Sholem Aleichem, Bialik, and others. In the exhibit’s section on “Bible Translations in Yiddish,” there were rare editions of Bibles in Yiddish, including translations by Buxtorf (16th century), Blitz and Witzenhausen (17th century), Mendl Lefin, and others. A special corner was dedicated to “Yehoash the Poet.” It included clippings from newspapers and fragments from Yehoash’s poetry. A large bust of the poet, moulded by the ten-year-old ghetto sculptor Volmark, greeted visitors to the exhibit.

This exhibit, and all other cultural institutions in the ghetto, were completely illegal. During the day, the entryway was hidden behind boards so that if the Germans conducted a search they would not discover it. The show was open only at night.

The Culture House at Strashun 6

One of the major cultural centres in the Vilna Ghetto was the Culture House at Strashun Street 6. Several institutions were located there: a library, a lecture hall, an archive, the Offices of Statistics and Addresses, and a museum.

Well before the war, the Mefitsey-Haskole Library was located at Strashun Street 6. When Jews were put into the ghetto, they saw hundreds of books from the library strewn on the pavement. Herman Kruk, a librarian originally from Warsaw, devoted himself to rebuilding the library. By 10 September 1941, books were once again available for borrowing.

Those who rarely picked up a book in normal times now flocked to the library. Books became their companions, a consolation in a time of distress. In the ghetto’s hiding places and secret cellars, books were read by the light of a thin wick or a tiny ray of sun penetrating through a window.

On 1 October, around three

thousand people were dragged to their death from the Vilna Ghetto. And on 2

October, 390 books were borrowed. The slaughters in the second ghetto continued

on 3–4 October. On 5 October, 421 books were borrowed from the library. By

November the population had decreased by forty percent, while the number of

books borrowed increased by almost a third. By the end of November 1942, the

number of books borrowed during the time of the ghetto exceeded the figure of

one hundred thousand. In recognition of this milestone the library organized a

festive morning, during which book prizes were

distributed to the first and latest readers.

A concealed space was built to house a reading room. It was always full.

Music

During the period of the roundups, before Jews were driven from their homes to the ghetto, Vilna’s musicians buried their instruments in the ground to hide them. Later, it was possible to slip into the sewer system situated beneath the walled-in streets of the ghetto to dig them up and bring them into the ghetto. This is how a symphony orchestra was established in the ghetto, directed by Volf Durmashkin.

The musicians worked as slave laborers in town. They managed to smuggle a piano into the ghetto. They found a piano in an abandoned Jewish apartment. Each musician was responsible for smuggling one piece. Once back in the ghetto, they located a specialist who managed to rebuild theinstrument.

The first performance of the symphony orchestra and its seventeen musicians on 15 March 1942 was greeted as a festival in the ghetto. It performed the Caucasian Sketches by Ippolitov-Ivanov, a Jewish potpourri by Max Geyger, and part of Franz Schubert’s Unfinished Symphony. The symphony inspired the ghetto population like mountain air for those with lung disease. It was worth fighting for beauty in the world.

________________________________________________________________________________________________

All excerpts from From the Vilna Ghetto to Nuremberg: Memoir and Testimony, appearing this fall, are reprinted with the permission of McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Suggested Reading

Yiddish Heroism, Hebrew Tears

For Avraham Sutzkever, life and work were not even slightly separate, since his was a life not merely shaped by poetry in a metaphorical sense but literally saved by it, when a poem of his produced an airplane.

A Book and a Sword in the Vilna Ghetto

If the destruction of Jewish culture and Jewish life were intertwined, then the reverse was also true: The rescue of books, manuscripts, Torahs, and so on was almost as much a form of resistance as the preservation of life itself.

“With a Wolf in One Eye”: Sutzkever in Israel

From his birth just outside Vilna in 1913, Abraham Sutzkever led a life that had merged, as though on a God-ordained path, with the fate of the Jewish people in the 20th century. It of course follows that that life would reach its culmination in Israel.

The Poet from Vilna

Avrom Sutzkever and Max Weinreich, a memoir.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In