Reprise of the Repressed

I was at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre one evening in November when a Nazi walked down the aisle and took a seat a few rows in front of me. It was about a month after the Hamas attacks in Israel, and on social media, in Jewish publications, and sometimes even in real life, I heard over and over that Jews needed to abandon the universities, if not the country itself, in the face of rising hatred. Videos of pro-Palestinian demonstrations on campuses prompted more than a few warnings that this was how things started in Germany in the 1930s. So the appearance of a Nazi in a Broadway theater, complete with black uniform, swastika armband, and vicious sneer, seemed ironically timely. Ironic because, of course, he was an actor in the show—Harmony, a musical by the ’70s pop hitmaker Barry Manilow—and while he was there to wring an emotion from what seemed a largely Jewish audience, it wasn’t terror but a familiar, even nostalgic kind of grief.

It’s pure coincidence that Harmony opened on Broadway just as American Jewry was facing a resurgence of primal anxieties. It is billed as a new musical because this is the first production on Broadway, but, in fact, it was first performed in San Diego in 1997 and has been staged in several places since. Last year, a production by National Yiddish Theater Folksbiene, featuring most of the current cast and creative team, won several off-Broadway awards. By a further coincidence, the show’s Broadway opening coincided with an off-Broadway revival of I Can Get It for You Wholesale, a little-known but surprisingly powerful musical from the early 1960s, whose view of Jewish life is the opposite of nostalgic.

Manilow, whose most well-known hits include “Mandy,” “I Write the Songs,” and “Copacabana,” and his longtime lyricist, Bruce Sussman, were inspired to write Harmony after seeing a documentary about the Comedian Harmonists, a singing group that enjoyed almost Manilow-like levels of success in Weimar Germany. Like later boy bands such as the Backstreet Boys or BTS, the Harmonists won huge audiences with their good looks, well-drilled routines, and sugary tunes. But when Hitler came to power in 1933, the fact that three of the group’s six members were Jewish put them in the Nazis’ crosshairs, and they were soon forced to split up. It was a sad ending but not a horrific one: the Jewish singers formed a new group abroad, the Gentiles did the same in Germany, and all six Harmonists survived World War II.

This history offers Manilow and Sussman the chance to tap two reliable sources of show business sentimentality. In the first act of Harmony, a ragtag crew of scrappy performers with big dreams decides to put on a show, overcomes some early setbacks, and ends up the toast of Berlin. Manilow evokes the spirit of the original Harmonists, if not their musical style, with upbeat songs like “We’re Goin’ Loco”—a Latin number reminiscent of “Copacabana”—which the group performs with Josephine Baker, played by Allison Semmes. They also find themselves rubbing elbows with celebrities such as Albert Einstein and Richard Strauss, both played with gusto, and elaborate hairpieces, by Broadway veteran Chip Zien. Zien’s main role is as the older version of one of the Harmonists, known as “Rabbi” because he quit the synagogue for the stage. In this guise Zien serves as the show’s narrator, and as the story darkens in act 2, it is up to him to deliver the second type of sentimentality: Jewish guilt.

Why, Rabbi berates his younger self, didn’t he insist that the group remain in New York after Hitler took power instead of returning home from their concert tour? It doesn’t take long for the Harmonists to realize they’ve made a mistake. That Nazi appears in the audience in a scene in which a performance by the Harmonists is interrupted by antisemitic jeers; he makes his way onto the stage and smoothly apologizes for the disorder, while heavily hinting that such unpleasantness could be avoided if the group’s Aryan members simply dropped the Jewish ones.

Later, at the climax of the second act, the aged Rabbi blames himself for not taking advantage of a chance meeting with Hitler—the Harmonists and the dictator found themselves on the same train—to assassinate him and avert the Holocaust. This improbable encounter is apparently part of the historical record, but in real life, assassinating Hitler wasn’t so easy; many actually tried during his twelve-year rule, including several members of the German military, without success. Still, Rabbi’s feeling of guilt inspires Zien’s eleven o’clock number, “Threnody,” a nervous breakdown in which he blames himself personally for the Holocaust while heartbrokenly reciting the Shema. “The truth of it is, you did nothing. / Like the thousands who followed, nothing! / Like the millions who stood by and watched and denied!” Zien sings angrily.

No one in the Broadway audience in 2023 can be blamed for letting the Holocaust happen. Yet the words seemed directed at us, and they hit their mark: I heard sniffs, gasps, and crying throughout Harmony, but especially in this climactic scene. In an earlier number, Rabbi’s non-Jewish wife, Mary, played with earnest delicacy by Sierra Boggess, insists on going into exile with the band’s Jewish members: “Where you go, I go,” she sings in the words of the biblical Ruth. See, Harmony seems to ask, what a righteous Gentile was willing to endure for the Jews? Have you in the orchestra seats made any comparable sacrifices?

So much of American Jewish popular culture sets out to shame the audience in this way that we must have a communal appetite for it. Setting aside movies like Schindler’s List (“I could have got more out. I could have got more,” Schindler berates himself) and novels like The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay (“Here he was, free in a way that his family could only dream of, and what was he doing with his freedom?” thinks the young refugee Kavalier in World War II New York), the best Jewish musicals have always made audiences feel good by feeling bad. In Fiddler on the Roof, the wedding of Tzeitel and Perchik, set to the bittersweet tune of “Sunrise, Sunset,” ends in a pogrom—a plot point copied in Harmony, in which a double wedding in a synagogue is shattered by Nazi vandalism. In Parade, the Jason Robert Brown musical about the lynching of Leo Frank, Leo goes to his death in the final scene with the Shema on his lips, like generations of Jewish martyrs.

Parade is a much better show than Harmony, but when it came to Broadway last year in a Tony-winning revival, it, too, was hailed as disconcertingly timely. If these shows written in the late 1990s perfectly reflect the Jewish anxieties of 2023, however, perhaps that is a sign that the anxieties themselves are not so timely—that is, they are not primarily caused by current events.

American Jewry is defined by a permanent cognitive dissonance. We are the most fortunate Jewish community since biblical times, yet we belong to a people defined by experiences of near-annihilation, from the Red Sea to Shushan to Auschwitz. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud advanced the concept of repetition compulsion, suggesting that an individual who undergoes a trauma often feels “obliged to repeat the repressed material as a contemporary experience instead of . . . remembering it as something belonging to the past.” Sometimes, as with Harmony, it’s hard to tell whether what we want from Jewish art is a catharsis that will help us purge this trauma or a re-creation that will allow us to repeat it. Sometimes it’s hard to tell in Jewish politics, as well—which doesn’t mean that the Jews don’t have real, present-day enemies.

One advantage of having a Nazi for an enemy is that, by being purely evil, he allows his victims to be purely good. Certainly none of the Jewish characters in Fiddler or Parade or Harmony does anything discreditable. This strong preference for innocence is, arguably, a post-Holocaust development in Jewish culture. In the first American Jewish novel, The Rise of David Levinsky, the socialist writer Abraham Cahan told the story of a ruthless Jewish capitalist who gets his start in the garment business by hiring scabs and stealing competitors’ designs. Levinsky becomes a millionaire, but after devoting his whole life to making money, he ends up with no wife or children and never fulfills his dream of becoming a learned man. In Jewish terms, this makes him a pitiable failure.

Jerome Weidman may have had David Levinsky somewhere in mind when he wrote I Can Get It for You Wholesale, his 1937 novel about a garment manufacturer named Harry Bogen who commits some of the same sins and others that are even worse. A quarter-century later, Weidman adapted the novel into a musical by the same name, which ran for almost a year but is only remembered today as the Broadway debut of a nineteen-year-old Barbra Streisand.

The stripped-down, star-packed production of Wholesale that ran for two months at New York’s Classic Stage Company last fall was a hot ticket for musical-theater aficionados, and it offered a sharp contrast to the schmaltz of Harmony. The songs, by Harold Rome, don’t include any lost masterpieces; the standout is still Streisand’s showstopper, “Miss Marmelstein,” in which Harry’s put-upon young secretary complains that no one ever talks to her familiarly: “Even my first name would be preferable / Though it’s terrible, it might be better / It’s Yetta.”

But Rome used the musical idiom of Broadway’s Golden Age with brassy confidence, and part of that confidence comes from a sense of being at home in Jewish New York. It’s often remarked that the composers and lyricists who created the modern Broadway musical were almost all Jews—Cole Porter may be the only exception. But like the studio heads who built Hollywood, these American Jewish pioneers preferred to keep the emphasis on the first of those adjectives. Rodgers and Hammerstein never wrote a Jewish show—even the peddler in Oklahoma! is a Persian named Ali Hakim—and neither did Stephen Sondheim.

Yet it wasn’t just the creators of these shows who were Jews. So were many of the ticket buyers. The Jewish population of New York peaked at two million after World War II, nearly a quarter of the city’s total. Even in 2023, it’s clear how intimately Wholesale spoke to and about this generation of New York Jews. They understood Miss Marmelstein’s embarrassment at her all-too-Jewish name and the way she covers it up with jokes. They knew what it meant to grow up poor in the Bronx like Harry Bogen, whose motto is that getting rich means getting even. And they understood how sex could be a way of getting even too. Harry is torn between Ruthie Rivkin, the nice Jewish girl his mother wants him to marry, and Martha Mills, the glamorous nightclub singer who becomes his expensive mistress. To make the contrast perfectly clear, in the original production, Martha was played by Sheree North, a blond, shiksa-goddess type.

At Classic Stage, both of Harry’s love interests were played by black actresses—Rebecca Naomi Jones (who is Jewish) as Ruthie, Joy Woods as Martha—and Harry is played by an actor of Italian descent, Santino Fontana. Yet the Jewish psychological and social dynamics of the love triangle were completely legible and authentic. It felt like a vindication of the increasingly old-fashioned idea that any human story can be told, and understood, by any human being with the talent to tell it.

Above all, this Wholesale—whose book was revised by Jerome Weidman’s son, John—understands the power and danger of making family the highest Jewish value. When Harry’s mother and fiancé meet his business partners at a party, they all sing the klezmerish number “The Family Way,” giving each other Yiddish nicknames as a sign of closeness: “Terichka meet Ruthele, Ruthele meet Terichka.” One of the main reasons Harry wants to get rich quick is so he can become a big shot by showering his loved ones with gifts.

But when the embezzlement that funded his largesse is exposed, Harry doesn’t hesitate to trick his partner, the meek Meyer Bushkin, into taking the fall and going to prison. Theft and fraud have their charming side, but this betrayal of a friend is unforgivable, and the show ends with a tableau of all the other characters gathering to say Shabbat prayers, as Harry is left alone in the dark.

Then as now, the ultimate Jewish punishment is expulsion from the community. By comparison, even being beleaguered and frightened together can be a kind of pleasure; at least it feels like home.

Suggested Reading

All That Is Solid

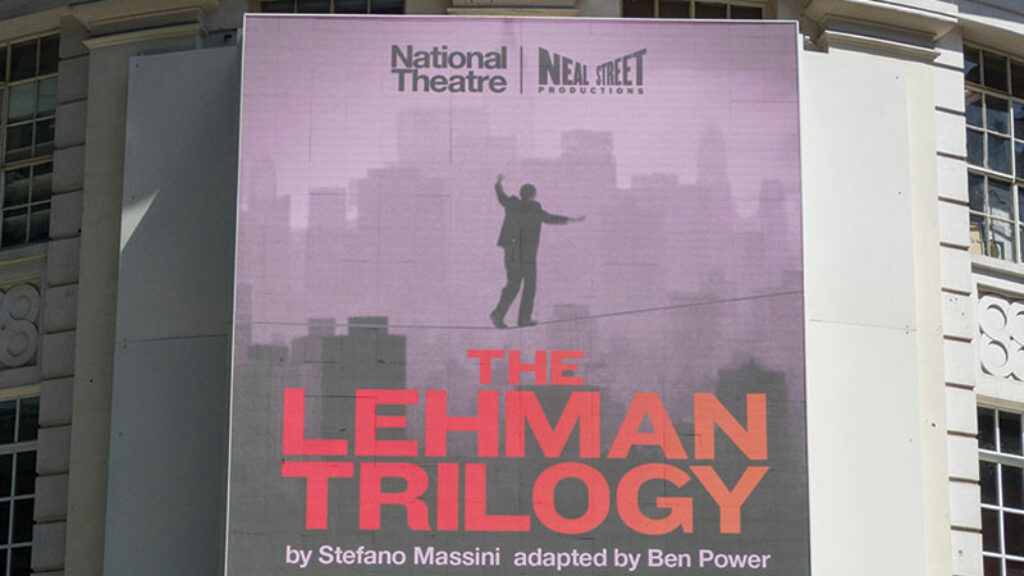

The Lehman Trilogy, both the novel and the play, are mythic in scale, using three generations of the Lehman family (one per section of the “trilogy”) as characters in a didactic pageant about capitalism, America, modernity—and Jewishness, which plays an unsavory role in the proceedings.

Tradition! Tradition!

Wonder of wonders! One of the most beloved musicals ever created far outstripped its own creators' expectations for its success.

Ruby Sees Red

"I’m still trying to wake up from this nightmare. I walk in the streets. I see parents with babies. I can’t look. I walk in Riverside Park, I see an older man hugging his granddaughter, and I almost start crying. We have been forced back into Jewish history, into the bloody raw part of Jewish history."

Charles Krauthammer’s Gift to Jewish Music

Best known for his weekly political column, Charles Krauthammer was also champion of Jewish music.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In