Lechaim!

Back in the 1960s, the Rheingold Corporation ran a bunch of TV commercials—mostly during baseball games, if I remember correctly—vaunting the popularity of its beer among all sorts of minority groups in New York City. What stuck in my mind, of course, is the one that claimed that Rheingold was the favorite brew of Jews in the metropolis where there were “more Jews than in all of Israel.” At the time, that was an accurate statistic, however many of them were actually Rheingold drinkers. What the commercial had no reason to mention was that Rheingold itself had a long history as a Jewish-owned company, starting with the beer’s first appearance in Brooklyn in 1883, when, as you might be surprised to hear, there were more Jews in Jerusalem alone than there were in all of Brooklyn.

I learned about the Liebmanns, German-born Brooklynites who launched Rheingold and owned the company for the next eighty years, from Marni Davis’s Jews and Booze: Becoming American in the Age of Prohibition, which I decided to reread before our annual JRB New Year’s bacchanal. Davis begins her story before Prohibition, when the American Jewish involvement in the alcohol industry wasn’t all that extensive but still interesting enough. There wasn’t much of a demand, for instance, for kosher wine in the United States during the early decades of its history, and the few Jews who required it were capable of making it on their own. Commerce in kosher wine seems to have begun in 1848, “when forty-two casks were sent from Jerusalem to New York City.” They didn’t find enough buyers, though, and it was decades before anybody tried anything like that again.

The man who started large-scale domestic production of kosher wine was a Bavarian immigrant to California named Benjamin Dreyfus, who, in the 1870s, “ran the largest and the most technologically modern winery in California.” Producing both kosher and non-kosher beverages, he soon became known as the “king of the Anaheim winemakers.” The Reform leader Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise was no champion of kashrut, but he couldn’t conceal his pride in Dreyfus’s achievements. Dreyfus died in 1886, just as the whole wine industry in southern California was being decimated by an agricultural ailment.

The story Davis tells of other Jews who made their fortunes in the alcohol business doesn’t heat up until the temperance movement begins to gain some traction in the second half of the nineteenth century. Jews then lined up mostly on the side of the “wets,” both because their own religion commanded the use of some alcohol and because they feared the Christianization of the public realm. “If religion and prayer are abused to wage war on liquor to-day,” Isaac Mayer Wise wrote in 1880, “they may be abused to-morrow, on the same principle precisely, to persecute . . . Freemasons, Catholics, foreigners, infidels, or anyone who . . . does not conform to vulgar prejudices.” American Jews didn’t deny the dangers of alcohol abuse. They just recommended that other people drink moderately and “do as we Israelites do,” as Philadelphia Rabbi Marcus Jastrow put it in 1874, a decade before he began to publish his Dictionary of the Targumim, Talmud Babli, Talmud Yerushalmi, and Midrashic Literature, which remains quite helpful today even if his advice to Gentile drinkers may no longer be so.

Neither the stance taken by leading rabbis nor the growing presence of Jews in the alcohol industry provoked the advocates of temperance or the prohibitionists to retaliate. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union “consistently extended themselves to Jewish sisterhoods and avoided anti-Semitic rhetoric,” and the early leadership of the Anti-Saloon League “eschewed direct criticism of Jews.” Things changed, however, with the gradual infiltration of populist antisemitism into the prohibitionist movement, especially in the South. In 1908, for example, soon after Georgia’s prohibition law went into effect, the itinerant minister John Cawhern denounced the “flat heeled, flat nosed, course [sic] haired, cross eyed slew footed Russian Jew whiskey venders [sic] whom the old Georgia politicions [sic] have licened [sic] to poison our boys.”

Prohibitionists didn’t win the day, or rather the decade of the 1920s, by targeting them, but once they succeeded in having the National Prohibition Act passed, American Jews found themselves in a rather unique situation, one that may have inspired a Ku Klux Klan-affiliated rabble-rouser to declare that, “My fight right now is against the Homebrew and the Hebrew.” Tiptoeing around the First Amendment, the new law “allowed Jews,” as Davis puts it, “to purchase kosher wine for use in religious rituals, and sacramental wine stores were established in Jewish neighborhoods all over the country as the 1920s began. These stores also served as wellsprings of bootlegged alcohol.” This wouldn’t have happened if there hadn’t been significant numbers of impecunious immigrant rabbis and non-Jewish impostors who didn’t play by the rules. Some “claimed new and enormous congregations filled with members named Houlihan and Maguire,” others “requested wine on behalf of fictitious or long-dead congregants, or sold their legitimately acquired wine permits to bootleggers.” Davis reports that “By 1925, the Bureau of Prohibition had determined that rabbinic authorization and sacramental wine stores were ‘the chief sources of the illicit liquor supply.’”

Needless to say, this was a source of great embarrassment to American Jews, especially after Henry Ford picked up on it and trumpeted to the world that they “did not favor Prohibition, but they did not fear it; they knew that it would bring certain illegitimate commercial advantages; they would be winners either way. Jewish luck!” Louis Marshall, the head of the American Jewish Committee, who tangled strenuously with Ford on other fronts, thought it would be a mistake to try to respond to him on this matter and sought instead to cut the ground out from under the crooked rabbis by getting the law changed. Jews, he thought, could make do with grape juice, as the halakha permitted. This went down very badly, however, with traditionalists. Even more importantly, the Catholic Church drew a line in the sand, protesting that it would never put up with a law that banned the use of wine. Marshall, too, had second thoughts and “sensing that the request for repeal of the exemption had been a step too far, decided to abandon this tactic.”

In the fall of 1923, a headline in the New York Times announced, prematurely, “FAKE RABBIS ELIMINATED.” Still, between 1925 and 1927, the government figured out ways to clamp down effectively on rabbinical lawbreakers and impostors. And by 1933, Prohibition was gone, at least in all of those areas where it mattered to any significant number of Jews. The story of American Jews and alcohol for the last eighty years is one of the making of a few big fortunes and the steady decline of the number of Jews in the business. Which is no reason for us not to have a lechaim on New Year’s Eve, especially when it coincides, as it does this year, with Shabbat.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

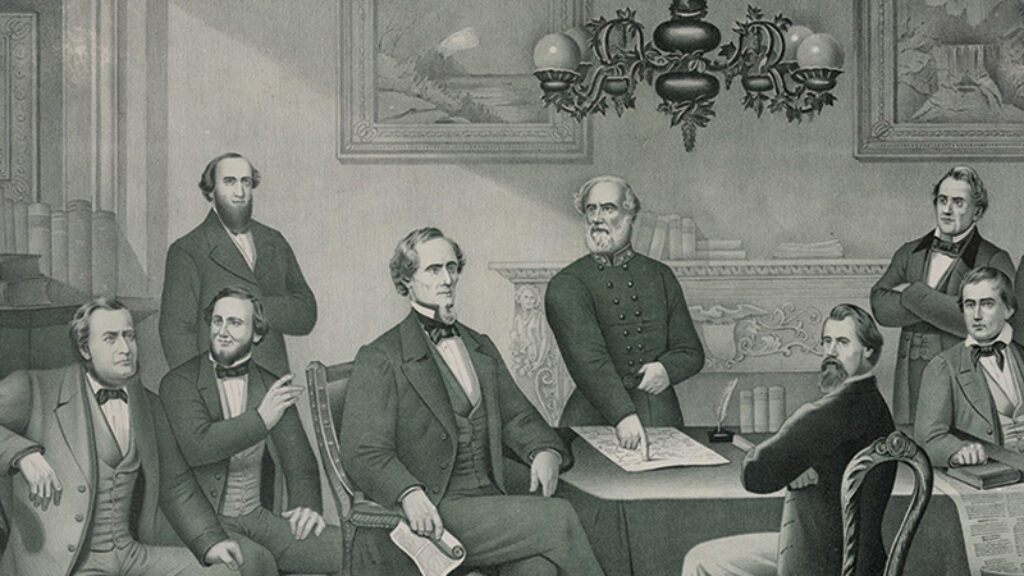

An Israelite with Egyptian Principles

Judah Benjamin was a brilliant New Orleans lawyer who became the most important cabinet member in Jefferson Davis’s Confederate government. He was, Senator Benjamin Wade correctly declared, one of the “Israelites with Egyptian principles.”

Working One’s Way Out

"When I first read Winter Vigil over a year ago, I was swept away; I hadn’t read any contemporary writing as good in a long time. I hadn’t known Steve Kogan could write like that. I hadn’t, it turned out, known very much about him."

Law, Justice, and Memory in Poland

Under the Law and Justice Party, Poland has just criminalized the life stories of its Jewish survivors. Here’s why.

Fog

Every spring for the last ten years, a fog has crept over Haim Watzman's life. It begins to dissipate on Yom Hazikaron, Israel's memorial day.

Albert Baumgarten

The table wine Kosher wine industry has flourished in the last decades. No longer wine so sweet/thick that you can cut it with a knife. There are quality table wines from all over the USA. I don't see a "steady decline of the number of Jews in the business."

Vern

With a title like that, I was indeed expecting a book as fun as it would be entertaining. I was looking forward to vignettes and personal accounts, unusual circumstances and consciences. Alas, aside from the opening unlikely scene of a Jewish federal agent busting a religious Jews for transporting liquor in a baby carriage, there's little to keep one's attention in this book that reads like a PhD thesis. There is much well-researched history here and it is a worthwhile read for interesting insights in Jewish political and social dynamics during prohibition. But if you are looking for a broader view of Jews in the alcohol industry generally or in the Bourbon industry specifically, there are better books. Don't get this just because of the cute title.

Michele Braun

My father, born in the early 1920s and immigrated to Brooklyn later in that decade, told a story of his out-of-work father, desperate during the depression to support his 5-person family. Apparently, someone offered my grandfather work concocting bathtub whiskey in the family's apartment. My grandfather stewed for a bit, needing income badly. Ultimately, he decided against it, fearing arrest more than hunger. Just a week or so later, the bootlegger was arrested and the liquor enterprise shut down.