We Agree on Herzl

Gil Troy initially responded to Allan Arkush’s review of his new book, The Zionist Ideas, in a comment on our website. We invited him to offer this fuller response.

You know a review has turned mean-spirited when you’re indicted for crimes you quite carefully didn’t commit. And a review actually does readers a disservice when it overlooks the book’s central intellectual framework and argument.

Reviewing my new book, The Zionist Ideas, which updates Arthur Hertzberg’s classic 1959 anthology, The Zionist Idea, professor Allan Arkush devotes 109 words to correcting my supposed misreading of Zionism’s founder, Theodor Herzl. That’s stunning because Arkush and I agree with Shlomo Avineri and Georges Yitshak Weisz that Herzl wasn’t mugged by anti-Semitism during the Dreyfus trial; his yearning for a Jewish state evolved.

Arkush writes: “Troy identifies [Herzl’s] direct exposure to the French crowds crying ‘death to the Jews’ following Dreyfus’s conviction as the key factor in his transformation into a Zionist.” I wrote in the introduction: “Herzl’s [Dreyfus] break through is also overstated. Like [Betty] Friedan’s feminism, Zionism had been simmering for decades. And Herzl wasn’t such a non-Jewish Jew. Some of his Jewish nationalist musings predated the Dreyfus trial.”

My capsule biography introducing some key Herzl texts notes that his reaction in Paris “had its roots in his earlier life”; that two years before Dreyfus “[t]he Jewish problem was now at the forefront of his attention”; but, yes, the trial “fully transformed him into a Zionist.” In writing “fully,” I gestured at a process that had culminated, not an abrupt conversion. One thing I have learned over the years as a teacher, colleague, and book reviewer is this: if you correct something, better correct correctly and not incorrectly—or, as in this case, don’t correct something that wasn’t incorrect in the first place!

Most outrageous is Arkush’s refusal to mention, even critique, what every other reviewer has acknowledged as the major contribution of The Zionist Ideas and its greatest departure from Hertzberg’s majestic work. The book broadens the conversation from Hertzberg’s 37 male thinkers to 170 thinkers, male and female, left and right, religious and secular, Ashkenazi and Mizrahi, Israeli and diaspora based.

The Zionist Ideas suggests a framework for organizing the Zionist conversation within six schools of thought: political, labor, revisionist, religious, cultural, and diaspora Zionism. I’m not claiming originality. The legendary Hebrew University historian of Zionism, Gideon Shimoni, among other scholars, tracks the ideological ferment that shaped the first five. But most often overlook the sixth stream, diaspora Zionism. Zionism began with diaspora Jews debating their futures; American Zionists dodged the personal quest but bought in—gradually—to funding the communal state-building project. Today, the relationship is more mutual, with diaspora Jews often seeking inspiration from Israel, not just tax receipts.

I organized the debate around these six schools because most Zionisms were hyphenated Zionisms—cross-breeding the quest for statehood with other dreams regarding Judaism or the world. Historians are often zoologists, categorizing ideas and individuals resistant to being forced tidily into a box. My anthology, with so many thinkers, required some categorizing, although it risked attacks that a particular author was better suited to a different school or too independent to be typed.

As a historian, I also grouped the thinkers within these six schools into three major phases of Zionism and made these the three major sections of my book: Pioneers: Founding the Jewish state (up to 1948); Builders:Actualizing and modernizing the Zionist blueprints (1948–2000); and Torchbearers: Reassessing, redirecting, reinvigorating (21st century). It’s unfortunate that Arkush couldn’t devote any space in a review of more than 2,400 words to that scheme. I would have undoubtedly learned from his analysis—as I did from other parts of the review that raised interesting questions about my choices for texts representing religious Zionism and socialist Zionism, in particular. (Note how Arkush used the categories, naturally.)

Moreover, the review’s title “Zionisms, Old and New,” advertises one of the book’s central aims. As another academic noted: “you added a second s to Zionism!” Discussing “Zionisms,” not one monolithic Zionism, frees us from partisans who weaponize the term “Zionist”to bash or boost.

Finally, a fair point Arkush raised, over which I agonized: from the start, the Jewish Publication Society and I envisioned a one-volume, accessible anthology expanding the circle of Zionist thinkers. Inevitably, that meant cutting. In essence, I crossed Hertzberg’s Zionist Idea with another classic, The Jew in the Modern World, by Paul Mendes-Flohr and Jehuda Reinharz. That book, like this new Zionist Ideas, showcases different positions in more readable 800- and 900-word selections (as opposed to three and four thousand-word manifestos).

It’s a reviewer’s prerogative to dislike a book, and it’s the author’s lot to bristle while seeking some blurb-worthy quotation like the one Arkush grudgingly offered: “Overall, his choices are good.” One might have thought that this was the key criterion for a good anthology.

Read Arkush’s reply to Troy here.

Suggested Reading

Wisdom and Wars

If it were fiction, Lawrence’s Seven Pillars of Wisdom would be the greatest English war novel.

Scaling the Internet

September 11, 2001 proved Akamai's technology could withstand anything. Cruelly, inventor Danny Lewin was the first to die in the attacks.

Moses Mendelssohn Street

Immortality in Jerusalem.

A Tale of Two Cohens: Purim in Montreal

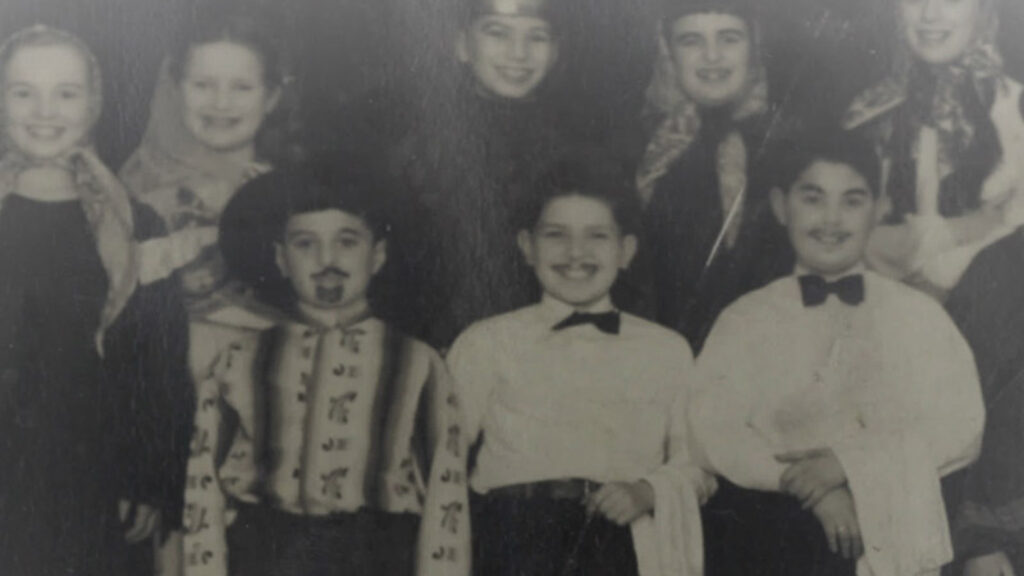

Lyon Cohen wrote and starred in Congregation Shaar HaShomayim's first Purim spiel in 1885--and then led the Montreal Jewish community for half-century. His grandson Leonard didn’t exactly follow his lead, but he does have a big grin in the cast photo of the 1947 Purim Spiel.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In