Zionisms, Old and New

I have been assigning Arthur Hertzberg’s classic anthology The Zionist Idea to students on and off for more than 30 years, and I have been complaining about it for just as long. Hertzberg’s collection of seminal writings by Zionist theoreticians from the days before Theodor Herzl to the founding of the Jewish state has many merits and no real peer. But, it’s a little bit too focused on fin de siècle analyses of “the Jewish problem” and insufficiently attentive to the variety of Zionist solutions to it. It presents the ideas of the European originators of socialist Zionism but doesn’t indicate how these ideas evolved, when put to the test, in early 20th-century Palestine. No doubt because he was embarrassed by it, Hertzberg also neutered Vladimir Jabotinsky’s Revisionist Zionism, rendering it difficult to recognize.

Gil Troy, an American-born immigrant to Israel and a prolific author, has now done something to The Zionist Idea that bears a certain resemblance to the book I had wished for: As the cover of The Zionist Ideas proclaims, he has “renewed” Hertzberg’s work. I am glad that someone has finally taken the initiative to do something of this sort, and I believe that Troy’s volume, like Hertzberg’s, has many merits. But I’m afraid that it doesn’t represent much in the way of an improvement over its predecessor, and in many respects it fails to measure up to it.

Hertzberg’s elegant and penetrating introduction to The Zionist Idea is one of the best essays on Zionist thought ever published. Troy, while acknowledging that it is “majestic,” has replaced it with a rather pedestrian mise en scène of the Zionist movement, one that celebrates more than it analyzes and one that leaves out much that is crucial. And he makes a lot of mistakes. For instance, Moses Mendelssohn never uttered the words Troy directly attributes to him: “Be a cosmopolitan man in the street and a Jew at home.” When the 19th-century Russian Jewish poet Y. L. Gordon wrote something similar, he was not, as Troy maintains, echoing Mendelssohn but at most channeling him.

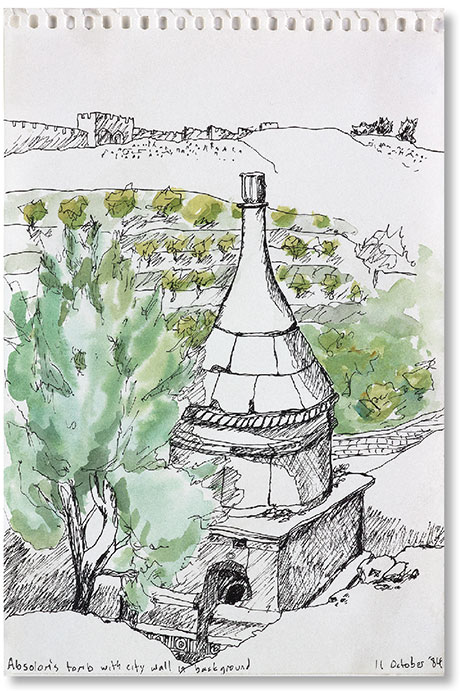

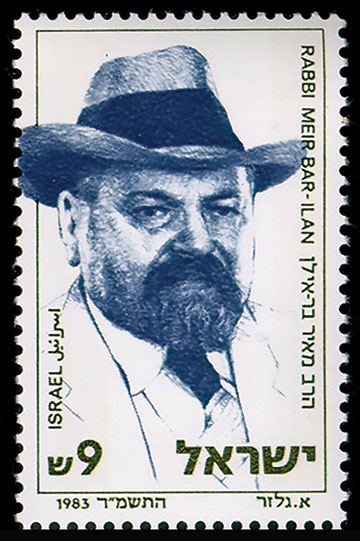

Zionism is incomprehensible apart from the age-old yearning of the Jewish people for restoration to the Land of Israel, and Troy not surprisingly evokes it in the first paragraph of his introduction. But why did it take so long for the Jews even to try to go back to their land? One can’t answer this question without taking into account the traditional Jewish belief that exile was the Jews’ punishment for their ancestors’ sins, a decree that they would have to endure patiently until God ultimately (and unpredictably) rescinded it by sending the messiah. Of this notion, however, there is scarcely any mention in Troy’s text, either in his introduction or in any of the excerpts he has selected, though he does refer, vaguely, to the early 20th-century Religious Zionist leader Rabbi Meir Bar-Ilan’s opposition to “rabbinic passivity” without explaining what that means. In fact, the only religious opponents of Zionism on whom Troy focuses directly are Reform Jews.

Troy’s sidestepping of the question of Orthodox quietism makes it difficult to understand one of the first selections in his book, Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai’s now-famous call in 1843 for the Jews to take the initiative and return to the Land of Israel on their own. In his short preface to his longer excerpt from the same text, Hertzberg reminded his readers that Alkalai’s call for Jewish action to hasten redemption was “at variance with the usual pious notion that the Messiah would come by miraculous acts of divine grace.” Hence, he notes, Alkalai had to argue that “self-redemption was justified by ‘proof texts’ from the tradition.” Troy’s selection includes one of Alkalai’s proof texts (“Return, O Lord, unto the tens and thousands of the families of Israel,” Numbers 10:36) but not the ensuing exegesis.

Like Hertzberg, Troy links Alkalai’s Zionist awakening to the early 19th-century nationalist revival in the Balkans, where he himself lived, and refers to the 1840 blood libel in not-too-distant Damascus as a key turning point, the crisis that convinced him (in the words of both anthologists) “that for security and freedom the Jewish people must look to a life of its own within its ancestral home.” Hertzberg apparently, and forgivably, doesn’t seem to have read what was, back in 1959, Jacob Katz’s only recently published article on messianism and nationalism in the teaching of Rabbi Yehuda Alkalai. The great Israeli historian showed that for Alkalai the lesson of the blood libel was not the vulnerability of the Jews but rather their new-found strength, as displayed by the Western Jewish saviors of the Jews of Damascus, Moses Montefiore and Adolphe Crémieux. This was, in Alkalai’s eyes, a sign of divine favor, the beginning of redemption, which he optimistically expected to be launched by the new Jewish grandees’ working their magic with Gentile potentates to obtain their assistance in returning the Jews to their land. The article in which Katz elucidates this subject has had a deep impact on relevant scholarship over the past 60 years.

If anti-Semitism didn’t inspire Alkalai to become a Zionist (avant la lettre), the idea that it was a severe and ineradicable threat to the Jews was a fundamental tenet of Zionism, and Hertzberg was correct to devote substantial attention to analyses of its roots and potency in the writings of Moses Hess, Leon Pinsker, Theodor Herzl, Max Nordau, Nachman Syrkin, and others. But if Hertzberg perhaps allocates more space than necessary to this, Troy is certainly guilty of going too far in the other direction. He lets his readers know what Pinsker thought about anti-Semitism but includes in his selections next to nothing of what the others listed here—or any other Zionist founders—had to say on this subject. Nor does he in his introduction include anything useful about the nature and extent of anti-Semitism in late 19th-century Europe. While saying very little of the impact on Herzl of his experiences at home in Vienna or in Germany, Troy identifies his direct exposure to the French crowds crying “death to the Jews” following Dreyfus’s conviction as the key factor in his transformation into a Zionist. This remains, as Shlomo Avineri has observed, “the common wisdom” on this subject, “but there is in fact no evidence of this, not in Herzl’s voluminous diaries nor in the many articles he sent from Paris to his newspaper in Vienna.” Avineri demonstrates that it was, on the contrary, “developments in the Austro-Hungarian Empire that led him to search for a Jewish homeland.”

With respect to socialist Zionism, Troy remedies none of Hertzberg’s deficiencies, but he does supply at least some of what the latter leaves out about Jabotinsky’s Revisionism. Instead of displaying only the spokesman for a Jewish state as he appeared before the Peel Commission in 1937, he allows his readers a glimpse of the militancy that no doubt discomfited Hertzberg, including Jabotinsky’s 1923 call for an “iron wall, that is to say the strengthening in Palestine of a government without any kind of Arab influence, that is to say one against which the Arabs will fight.”

Another virtue of the first part of The Zionist Ideas is its inclusion of pre-1948 voices absent from The Zionist Idea, among them a few women (Hertzberg’s volume was all male). This does not make up, however, for the drastic abbreviation of most of the selections he carries over from Hertzberg or for the errors he makes in the rewritten introductions to some of them, as well as in his introductions to the new excerpts. It is something of an overstatement, for instance, to say that Horace Kallen, who coined the term “cultural pluralism,” is “recognized as the father of multiculturalism.” More to the issue at hand, it is not true that Rabbi Meir Bar-Ilan “spearheaded the Religious Zionist opposition to Herzl’s Uganda plan” at the first Zionist Congress he attended. Bar-Ilan did indeed oppose the Uganda plan, but in doing so he broke with the majority of Religious Zionists at the time, who voted in favor of it. That Troy does not know this shows how little he understands of the early ideology of the religious wing of Zionism.

Having reduced Hertzberg’s more than 500 pages of documents predating Israel’s independence to 138, Troy has plenty of room for a large gallery of more recent Zionist thinkers and activists of all stripes, from the diaspora as well as Israel. Overall, his choices are good. I was especially pleased to find excerpts from the eloquent letters of Alex Singer, an American immigrant to Israel who died in battle in Lebanon in 1987, four years after I had him as a student in a class at Cornell, the first one, as it happens, in which I assigned The Zionist Idea.

The large majority of the individuals Troy has assembled in the second part of his anthology are formidable thinkers, men and women whose allegiance to Zionism is the result of deep, nuanced reflection and wide experience. The problem is that Troy has squeezed over a hundred of them into less than 500 pages. You can’t get very far into the complex arguments and ideas of Bernard Avishai, Chaim Gans, Ruth Gavison, Yeshayahu Leibowitz, Ze’ev Maghen, Simon Rawidowicz, Yael Tamir, or Ruth Wisse by reading a page (or three) of their work. In fact, at this soundbite length these very different thinkers tend to merge into each other, forming a vague, illusory consensus.

Troy, to be sure, wanted to include as broad a range of figures as possible while adhering to what he tells readers was the word limit imposed by his publisher, but he has also made it his goal to illuminate “the larger Zionist puzzle—an ever-changing movement of ‘becoming,’ not just ‘being,’ of saving the world while building a nation.” He sought to assemble texts that would “help compare what key thinkers sought and what they wrought, while anticipating the next chapters of this dynamic process.” In doing this Troy has been partially successful, but here, too, there are problems.

What happened on the ground in Palestine to the socialist Zionist ideas of Syrkin and Borochov is something that Troy does only slightly more than Hertzberg to illuminate (by excerpting a page from Rahel Yanait Ben-Zvi’s The Plough Woman about the joys of agricultural labor). The endless theorizing among the Yishuv’s Labor Zionists about the true meaning of socialism finds no echo at all in his volume. Troy does note that “David Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, and their comrades were hard-nosed pragmatists more than pie-in-the-sky universalists. The early state’s defining institutions reflected this Labor Zionist mix, especially the military elite unit, the Palmah; the agrarian commune, the kibbutz; and the mighty workers’ union, the Histadrut. They got the job done.” But where did this pragmatism come from, and how did its champions overcome the Marxist theorists with whom they had come to disagree? One has to look elsewhere to find out (start with Jonathan Frankel’s Prophecy and Politics: Socialism, Nationalism, and the Russian Jews, 1862–1917 and continue with Mitchell Cohen’s Zion & State: Nation, Class, and the Shaping of Modern Israel).

Troy doesn’t shed any more light on the decline of Labor Zionism’s pragmatic socialism than he does on its origins. He does say a few vague words about “persistent problems” that made its leaders “look less effective and less romantic, especially as Marxist collectivism retreated globally,” and he reproduces a paragraph from a statement by leading Israeli historian Anita Shapira lamenting its demise, but he presents no theoretical defenses of it and no critiques of it. His two chapters on post-1948 Labor Zionism focus on other matters, mostly its leaders’ notions of how to attain peaceful relations with the Palestinians and the Arab world.

Troy provides ample evidence of the general readiness of Labor Zionists in recent decades for territorial compromise with the Palestinians. He makes it equally clear that the heirs of Revisionist Zionism have had very different ideas. He also allows his readers a glimpse of the Religious Zionist ideology that powerfully spurred the movement to settle and retain the territories captured in the Six-Day War—but only a glimpse. The sole example Troy presents of the thinking of the leading figure in this camp, Rabbi Zvi Yehudah Kook, is a one-page excerpt from his famous visionary oration in May of 1967, in which he spoke longingly of the parts of the Holy Land that still lay beyond Israel’s borders. In his introduction to this text, Troy comments on Kook’s “fiery nationalism” but says nothing about his messianism. Elsewhere, he comes closer to acknowledging the theological dimension of Kook’s nationalism when he notes how Kook’s students, the founders of Gush Emunim, considered their program to be somehow bound up with “the total redemption of the Jewish people and the whole world.” Troy is of course correct, but that conviction is just the tip of the iceberg.

Troy mentions in passing religious nationalists such as Haim Druckman, Hanan Porat, Moshe Levinger, and Yoel Bin-Nun, all of whom adhered, at least for a time, to Kook’s radically messianic ideology. But he does not otherwise admit them into his anthology. At least one of them should have been included in a volume devoted to the elucidation of what key figures “thought and wrought,” given their impact on the last half-century of Israeli history. The best view that The Zionist Ideas offers of their ideas is an excerpt from a 2005 critique of their ideology by Rabbi Yehuda Amital, another student of Rabbi Kook who had once fully shared these ideas but later abandoned them. “The students of Rav Zvi Yehuda Kook,” Amital writes, “explained that the ‘beginning of the redemption’ refers not to the Jewish nation dwelling in the Land of Israel, but rather to the absolute sovereignty of the Jewish nation over all parts of Eretz Yisra’el.” This is instructive, but it is not enough. A better anthology would have given Rabbi Amital’s very important one-time allies an opportunity to say this, and more, for themselves.

Of course, it is easier to find fault with an anthology like Troy’s than to undertake one, and I probably wouldn’t do so now if The Zionist Ideas wasn’t aimed at supplanting Hertzberg’s (flawed) classic. I don’t know if I’ll teach another course on the history of Zionism, but it would be unfortunate if those who will can’t continue to assign Hertzberg’s book until something truly better comes along. It does, of course, need to be supplemented by other texts—including selections from the authors represented in The Zionist Ideas, albeit longer, richer, and more revealing ones than those that Troy has assembled.

Of the dozens of authors joined together in Troy’s book, the most recent to publish a comprehensive statement explaining his own Zionism is Yossi Klein Halevi, the popular author of Like Dreamers: The Story of the Israeli Paratroopers Who Reunited Jerusalem and Divided a Nation and, just as relevantly, At the Entrance to the Garden of Eden: A Jew’s Search for Hope with Christians and Muslims in the Holy Land. In his new small book, Letters to My Palestinian Neighbor, Halevi elaborates on the themes he outlined in 2015 in the “Jewish Centrist Manifesto,” included by Troy in the last section of his volume. Halevi’s book is not a treatise but a plea for understanding, an attempt to present the Zionist cause to unsympathetic ears in a way that would enable its adversaries to abandon their prejudices against it and seek to come to terms with it.

While firmly fixed within the Zionist tradition, Halevi does not have frequent recourse to it. His Zionism is religious, but he doesn’t cite a single Religious Zionist authority, from Alkalai to Kook (or Amital). Indeed, he pointedly avoids affirming one of the most fundamental tenets of most versions of Religious Zionism. The “settlement movement” and others might hold that the Torah teaches that “God has given this land to the Jewish people,” but Halevi prefers what he calls “another religious way” of seeing things, one that precludes any claim to exclusive Jewish ownership of the land.

(Photo by Gili Yaari/Flash90.)

Unlike Troy, Halevi spells out the traditional idea that exile was a punishment for the Jews’ ancient sins, but only a temporary one, since ultimately “the prison sentence of exile would end and God would retrieve them from the most remote corners of the earth, as our prophets had predicted.” Without professing in so many words that God has done what the prophets foretold, he declares, “We have returned to our place of origin, just as Jews have always believed would happen, to reconstruct ourselves from disparate communities back into a people.” Just as? Perhaps that’s a bit much. As the great scholar of Jewish thought Aviezer Ravitzky has often observed, no Jews prior to modern times ever anticipated an ingathering of the exiles that would occur without the appearance of a messiah and would result in the establishment of a state in which halakha was not the law of the land.

Jewish theologians disagree, of course, over the question of whether this unanticipated development reflects the behind-the-scenes movements of the hand of God. Halevi, for his part, does not adduce biblical proof texts that it was, according to God, time for the Jews to go home. Why should he? Unlike Alkalai and other Religious Zionist thinkers, he isn’t primarily aiming to influence Jews here; he’s reaching out, he tells us, above all to Arabs, the religious Muslims among them in particular. For them, what the Jewish scriptures authorize or do not authorize doesn’t really matter, since, in their eyes (though Halevi doesn’t note this), they are, after all, corrupted.

In any case, Halevi seeks to convince his main audience less with texts than with sentiments. “Most Israelis,” he maintains, “are people of faith—if not necessarily in conventional religion, then surely in a life of meaning. Israelis sense that their very existence—speaking a resurrected language in a recovered homeland—is a miracle. ‘When the Lord returned the exiles to Zion we were like dreamers,’ wrote the Psalmist. Being Israeli is like awakening into a dream.” But Halevi doesn’t just invite his readers into his “spiritual home.” Like most Zionist thinkers, he insists on the Jewish need for a state.

I need a Jewish state. Not a state only for Jews—even after partition a substantial minority of Palestinian citizens of Israel will remain in its borders—but a state where the public space is defined by Jewish culture and values and needs, where Jews from East and West can reunite and together create a new era of Jewish civilization.

Halevi speaks of the Jewish need for a state also in a less elevated sense, reminding his readers of the suffering that Jews have undergone on account of their statelessness. He is very reluctant, however, to point to the Holocaust as a justification for the creation of a Jewish state. He makes virtually no mention of Hitler or the Nazis until his last chapter, and then refers to the massacre of European Jewry (including his own grandparents) not to reinforce the Jewish need for a state but only to account for contemporary Israelis’ “abhorrence for victimhood” and constant vigilance. For Halevi, it is not suffering but dreaming that constitutes the real heart of the Jews’ story.

Halevi’s own dream of Jewish revival is frankly ethnocentric, but it is a dream that need not come at the expense of the Palestinians’ sacrifice of their own legitimate but conflicting dream with respect to the very same land. His religious Zionism is a conciliatory one, involving a readiness for territorial compromise with the Palestinians on the West Bank and in Gaza, provided it is compatible with Israeli security needs. He hopes that the Palestinians affected by his story will recognize that painful compromise is the only reasonable choice when right contends with right. More than that, he hopes that such Palestinians will find in Islam the resources for accepting such a resolution of their conflict with Israel.

At bottom, Halevi’s new book is not so much an appeal from a Zionist to anti-Zionists as a call from a religious Jew to religious Muslims to accept the existence of a Jewish state on the grounds of a common faith in a beneficent God and humanity. Explicitly taking exception to the broader agenda of many faithful Jews, who see no room for compromise over the Land of Israel, Halevi hopes that his scaled-down, peaceable vision of coexistence in the Holy Land will find a ready hearing—or some hearing, anyhow—among the people whose calls to prayer regularly echo across West Bank neighborhoods to his own house, on the outmost edge of Jewish Jerusalem.

Of the well-known obstacles that Islam places in the way of recognition of the legitimacy of any kind of Jewish state Halevi says nothing. He does, however, provide us with several examples of broad-minded Palestinians with whom he has interacted in the past, and he clearly hopes that there are more such people just over the horizon. In his initial “Note to the Reader,” he provides a link to a free downloadable Arabic version of the book, and it has elicited some interesting responses from Palestinian and Arab readers. Still, when reading this, I couldn’t help thinking of the time capsules NASA sends into space to represent our civilization. Will Yossi Klein Halevi’s book turn out to represent the hopes of a 21st-century liberal religious Zionist, or is it, rather, an early document of a new theological-political opportunity?

Gil Troy responded to this review, initially in a comment, and then more fully in a piece found here. Allan Arkush’s reply to Troy can be found here.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Heaven from Torah: An Interview with Shai Held

A conversation on reading the Torah theologically, the future of American Judaism, and Jewish–Christian relations.

Early Modern Mingling

How the Jews became modern.

Another Round with Norman Mailer

Norman Mailer had the gift of enlivening everything he touched. And he touched almost everything, from politics to Hollywood to Sports. But his Jewish novel stayed in the drawer.

Animal Foible

The author of Life of Pi trivializes the Holocaust.

Gil Troy

You know a review is going to be churlish, when an historian is taken to task for using the word "echoing" not "channeling" -- to link one writer's idea with its originator/the person who articulated it before. Read the dictionary - "echo" is about (not necessarily exact) imitation, reverberation, a "remnant or vestige" -- "channeling" is defined as "professedly entering a meditative or trancelike state to convey messages from a spiritual guide." So it is more accurate to write what I wrote, that Y.L. Gordon was echoing not channeling Moses Mendelssohn... But you know the review -- and reviewer -- has turned downright mean spirited when he indicts you for a crime you most specifically and quite carefully DIDN'T COMMIT. Professor Arkush devotes 109 words to correcting my supposed misreading of Herzl. He writes: "Troy identifies his [Herzl's] direct exposure to the French crowds crying 'death to the Jews' following Dreyfus’s conviction as the key factor in his transformation into a Zionist." I wrote: "Herzl’s breakthrough is also overstated. Like Friedan’s feminism, Zionism had been simmering for decades. And Herzl wasn’t such a non-Jewish Jew. Some of his Jewish nationalist musings predated the Dreyfus trial." Hmmm. Maybe I'm not such an idiot, after all. It is of course a reviewer's prerogative to dislike a book. And it's the author's role to take umbrage and nevertheless hope he can scratch out a blurb-worthy quotation like the one Arkush reluctantly offered: "Overall, his choices are good." Fortunately, many other people have responded to the Zionist Ideas enthusiastically -- so I will simply ignore this flawed and unfair review - and hope others do too...

asmith

The Jewish Review of Books has invited Gil Troy to respond further in our pages. In any case, Allan Arkush will respond. In the meantime however, Arkush points the interested reader to page 12 of Troy's Zionist Ideas:

“In 1894 Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish captain on duty with the French general staff, was accused of spying for Germany. Herzl provided his Vienna paper with regular accounts of the Dreyfus trial and its effect on French public life. He was present at the Ecole Militaire when Dreyfus was stripped of his epaulets and drummed out the gate in disgrace. For Herzl this moment was a hammer blow. The howling of the mob outside the gates of the parade ground, shouting 'A bas les Juifs'—"down with the Jews'—fully transformed him into a Zionist."

Gil Troy's full response to Allan Arkush can be found here: https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/uncategorized/4725/we-agree-on-herzl/

Arkush's reply to Troy can be found here:

https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/uncategorized/4726/we-do-not-agree-on-herzl-and-we-still-need-hertzberg/