In Memory of Judah Maccabee

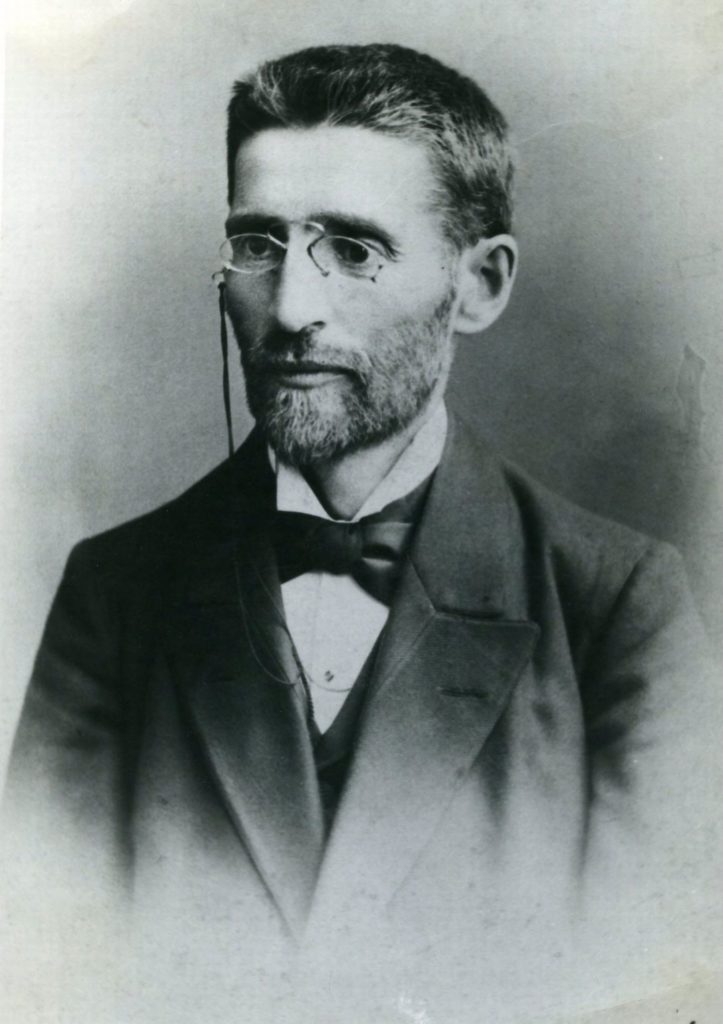

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, the father of modern Hebrew, spent the first days of the Hanukkah of 1893 in jail. The Turkish authorities in Jerusalem had imprisoned him on account of an article that appeared in his newspaper, Ha-tzvi, ten days before the holiday. Composed by his father-in-law, Shlomo Naftali Hertz Jonas, who was also put in jail, this short piece bore the seemingly pious title of “Mitzvot tzrikhot kavana”(commandments require intention). To some it must have looked like a comment on the longstanding and well-known rabbinic debate about whether this was indeed the case. But it was something else altogether.

Jonas’s complaint was that the Jews who performed the commandment of lighting the Hanukkah candles and inserted a special holiday prayer into the daily Amidah paid no attention to the true significance of their actions. They effusively thanked God for fighting on their behalf against the ancient oppressors who sought to uproot their religion. “But who was God’s emissary? Who was the warrior?” Judah Maccabee, of course. Yet it was as if he never existed. The prayer doesn’t mention him at all! We pay no attention to this great hero, Jonas lamented, from whom we could learn a great deal about the love of our land and the love of our people—the man from whom we could learn how “to defend ourselves, to gather strength, and to go forward.”

This stirring praise of an ancient Jewish hero wouldn’t have had any major repercussions had not Ben-Yehuda’s inveterate enemies, the leaders of the ultra-Orthodox communities in Jerusalem, distanced themselves from it loudly and publicly. “We and the rest of the Jews living securely under the rule of our lord and king, the Sultan, may he be exalted, are loyal subjects of our king and wash our hands of this strange article as well as everything else published in Ha-tzvi.” Worse accusations of disloyalty were no doubt made in private, leading the Turkish authorities to incarcerate both of the dangerous subversives, the writer and his editor.

What happened next is explored in detail in Yehoshua Kaniel’s Ben-Yehuda in Prison, 1893: A Selection of Contemporary Correspondence (Yad Izhak Ben Zvi Publications, 1983). From this volume one can learn a lot about the way the new Yishuv fought to defend itself against its adversaries and how Ben-Yehuda and his father-in-law succeeded in escaping their clutches. The book does not contain, however, any further discussion of Jonas’s chief grievance: the erasure of Judah Maccabee from the Jews’s memory.

One could make pretty much the same complaint today. A lot, of course, has changed in the past century and a quarter. In many popular retellings of the Hanukkah story, God now plays a smaller role than theMaccabees. In Israel, they are hailed in just the way that Jonas would have wished; in the Diaspora, they are portrayed as bold fighters for religious freedom. But even the Maccabees’s admirers usually have, for the most part, only a very blurry picture of them. Most of them know nothing more than that their victory over the Seleucids was an occasion when, as the prayer has it, “the mighty were delivered into the hands of the weak and the many into the hands of the few.”

But is this really true? Were the Maccabees actually underdogs? Everyone used to agree that the Israelis were outnumbered in their War of Independence, until the arrival of the revisionists who have sought to instruct us otherwise. Is there someone out there who says that Judah and his band, no less than their descendants in 1948, actually had a numerical advantage most of the time?

In fact, there is in Israel a noted historian of the SecondTemple period, the marvelously named (by his parents, I should note, and not, as one might suspect, by himself) Bezalel Bar-Kochva, who has written something fairly close to this and, by his own account, has paid a price for doing so. An emeritus professor of Jewish history at Tel Aviv University, and a former education officer in the IDF’s Central Command, Bar-Kochva didn’t set out to be provocative. But in the aftermath of the Six Day War, inspired by Israel’s conquest of the territory delineated in the literary accounts of the Maccabees’s exploits, he focused his academic work on determining what had really happened on those ancient battlefields.

Only after he developed an expertise on “the other side,” the Seleucid army, and wrote a doctoral thesis on it in England (that later became a book, The Seleucid Army: Organization & Tactics in the Great Campaigns), did he publish anything relevant to the Maccabees. In spinoffs from his thesis that appeared in the academic journal Zion in1973 and 1974, Bar-Kochva distinguished between the period prior to the purification of the Temple in 164 B.C.E., when the Maccabees were indeed outnumbered but achieved impressive success in guerilla warfare, and the period that followed, when Judah’s forces, having proved themselves to Jews who had previously been sitting on the fence, grew considerably stronger and acquired much better equipment. In some of their later battles they outnumbered the Seleucid forces and, for that reason, were able to enjoy victories over them in conflicts even on level terrain.

In a 2017 lecture, Bar-Kochva describes how his conclusions were at first well received, in part because some people were all too aware, in the immediate aftermath of the Yom Kippur War, of the dangerous consequences of being too confident that the favored few could easily defeat much larger forces of the iniquitous many. Several years later, however, when he incorporated his conclusions into a Hebrew book on the Maccabees, things proceeded differently. The trouble began when Ha’aretz published an interview with Bar-Kochva under the sensationalist title “The Slaughtering of Sacred Cows,” in which, he felt, his forthcoming book was badly misrepresented.

Other newspapers soon produced attacks on Bar-Kochva. A delegation of professors (who hadn’t read the book but only what was in the newspapers), led by a historian of Hungarian Jewry, showed up at the headquarters of his publisher, the Ben-Zvi Institute, demanding that copies of the book not be put on sale (or even be burned). One of the people from the Institute’s press whined to Bar-Kochva over the phone: “Gevalt! What are they doing? They’re ganging up on me. They say you are desecrating kodshei Yisrael.” Instead of yielding to pressure, however, the press’s director convened a panel of experts, led by the outstanding professors Joshua Prawer and Ephraim E. Urbach, who had nothing but praise for the volume, and in accordance with their recommendation went ahead with publication.

Bar-Kochva’s Hebrew book on the Maccabees, published in1981, served as the basis for his Judas Maccabaeus:The Jewish Struggle Against the Seleucids, which was published by Cambridge in 1989. For the lay reader who wants to know the truth about Judah Maccabee, it might not be the best place to start—given its scholarly nature—but there’s certainly no better place to go. Among many other things, it provides an illuminating account of the battle of Elasa, where the badly outnumbered Judah met his death in 160 B.C.E.

That Judah, the great victor of the Hanukkah story, ultimately died fighting the Seleucids is something that surprisingly few Jews know. But it is a fact that should not tarnish his memory. As Bar-Kochva puts it at the end of his book: “Judas Maccabaeus lost his last battle, but paved the way to the victory as a whole by developing a large and well-equipped army, which, though defeated at Elasa, later on by its very existence forced the Seleucids to come to terms with, and concede to, the Jewish demands. The real test of military leaders has always been in the endurance of their achievements rather than in brilliant one-time strategies.” Judah Maccabee was, then, despite his ultimately unfortunate fate, just as Shlomo Naftali Hertz Jonas said, a man from whom we could certainly learn how “to defend ourselves, to gather strength, and to go forward.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Hanukkah and State: The Hasmonean Legacy

The exchange between Rabbi Riskin and Rabbi Sacks on Jewish power and politics is illuminated by the history of Hanukkah.

Raising the Asmonean Banner

Two teenaged sisters wrote surprisingly sophisticated and moving poetry about the Maccabees and a medieval massacre.

Fateless: The Beilis Trial a Century Later

The fame of Mendel Beilis—falsely accused of murdering a Christian boy in Russia 100 years ago—was lavish, if bitter and short-lived.

Requiem for a Luftmentsh

Were Saul Bellow and his friend Isaac Rosenfeld the last Jewish intellectuals of their kind?

Peter Heiman

In recent times I have read suggestions that the main conflict of that time was between those Jews who leaned toward assimilation to the predominant (and generally tolerant) Greek culture and those, led by the Maccabees, who opposed it. I would appreciate Dr. Arkush's opinion on this. I often wonder, as a liberal Jew, which side I would have been on back then.