The Old Country, Twice Removed

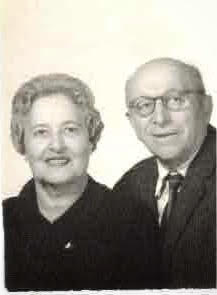

I feel a certain sense of belonging to the city of Kiev, with only the smallest reasons for doing so. I’ve never been there, but my maternal grandparents spent the first part of their lives in the general vicinity. My grandfather had a way of mentioning the Kiev guberniya (province) that made it sound to me, when I was a boy, like it was our place in the Old Country—and more than half a century later, it still does.

Zayde Shmuel didn’t talk very much about his life before coming to the United States; Bubba Minnie wouldn’t let him. While his horizon had been formed there and had barely changed after he emigrated, his wife felt as if life hadn’t really begun until they came to America. Invariably, when he tried to say something about the years before that, she would command him to be silent. Shrugging his shoulders and muttering something about her being the boss, he would always obey.

I can recall only two memories that Bubba Minnie herself ever shared with us about her pre-American existence. Once, while I was surveying the bounteous harvest of my mother’s vegetable garden, she reminisced happily about how, when she was a little girl, she had come home one summer day and seen the whole roof covered with ripening tomatoes—everywhere there were pomidorn, she said, using the Yiddish word, derived from the Russian, derived from the Italian.

Then there was the story about how, shortly after the Bolsheviks took over her town, they had confiscated all of her family’s light bulbs. (My forefathers in the region were people of means, but not of great means.) When she learned what had happened, she marched down to party headquarters and demanded that Garber—the man in charge, who happened to be a cousin—let them keep at least one bulb! According to her, he did.

Should we believe this story? There is, of course, the evidence of Zayde Shmuel to show how Bubba Minnie could make a man listen to her. But he was—with all due respect—a pushover. Garber, one has to assume, was a different story. But even if she didn’t really succeed in salvaging a light bulb, even if she never had the guts to utter so much as a word of rebuke to the new village potentate, I still relish this tale as evidence in itself of my family’s early and proud resistance to communism.

None of this—whether it happened or not—took place in Kiev itself, only nearby. That’s close enough, however, to give me a sense of kinship with the city. While this connection has never made me especially curious about present-day Kiev, not even when the Orange Revolution thrust it into the headlines, it has just now prompted me to read a fairly recent book about the city’s Jewish community around the time that my grandparents lived in the Kiev guberniya, Natan M. Meir’s Kiev, Jewish Metropolis: A History, 1859–1914.

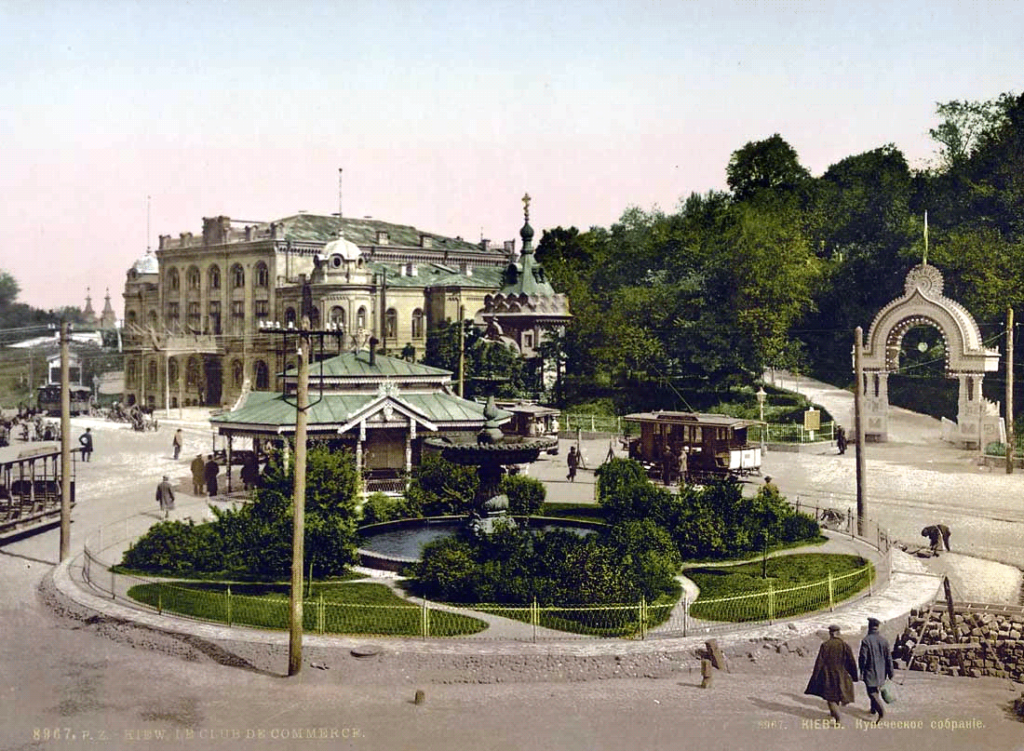

There had been a small Jewish community in Kiev in the early 19th century, Meir reports, but it had been exiled in 1835 when the city was officially excluded from the Pale of Settlement. Reforms introduced by Tsar Alexander II reopened the city to limited Jewish settlement in 1859, and from then on Jews from all over the Pale strove incessantly to make their way, legally or not, into the newly burgeoning economic center. Some, like the famous sugar magnate Lazar Brodsky, prospered mightily; others just managed to hang on. The community’s leaders constructed hospitals, synagogues, and schools, and they acculturated quite rapidly. The Jews’ increasingly visible presence in the city led to accusations that they were attempting to dominate it, which fed into the pogroms of 1881 and 1905. Just how many Jews lived in Kiev by 1914 is difficult to say since so many of them were there illegally, but there may have been as many as 75,000 of them, a number that would have made them one-sixth of the total population.

Meir’s book provides a highly informative account of a critical half-century in the life of Kiev’s Jewish community. Compared to some other swelling European metropolises in which masses of Jews were piling up in the 19th century—Berlin, Vienna, Budapest, Warsaw, Odessa—Kiev sounds like it was, most of the time, a rather dreary place. In his entire book, Meir describes only one incident that I would like to have witnessed, the writer Eliezer Friedmann’s “first evening in Kiev in 1893”:

[P]eople started gathering at his brother-in-law’s house for what he assumed was a meeting—especially since one of the arrivals was Sholem Aleichem. Instead, they set up cardboard-covered tables and threw themselves into cards, the Yiddish writer as enthusiastically as everyone else, one hand holding his cards and the other a drink or a leg of goose. In the morning, Friedmann found Sholem Aleichem in the same place, asleep on some chairs.

The great Yiddish writer lived in Kiev for many years, and the area was the setting for some of his best-known writing, including The Adventures of Menachem-Mendel and the Tevye stories. (“Boiberik” is a pseudonym for Boiarka, which is only about 12 miles southwest of Kiev.) But the city was not exactly a literary capital. “[I]n 1890, it had only 38 bookstores compared to Moscow’s 205, Warsaw’s 137, and Odessa’s 68. Even Saratov had more bookshops than Kiev!” In a letter to the Yiddish and Hebrew writer Mendele Mokher Seforim, Sholem Aleichem sought to explain the obliviousness of the city’s Jews to the latter’s works:

You have forgotten that Yehupets [Kiev] is not Odessa. In Yehupets, even if someone bursts, he will die a cruel death trying to find a copy of ‘Fishke’ or ‘Susati’ (My Horse)—they are not to be found. This hole which is Yehupets, may it go up in flames!

Three years after Sholem Aleichem wrote this letter, in the revolutionary year of 1905, things did indeed go up in flames, and he himself fled to New York. But bad as 1905 was, it was nothing compared to what was yet to come. I regret that I did not get to hear Zayde Shmuel’s account of more of what he had witnessed in 1917, but I can well understand why Bubba Minnie always shut him up.

Suggested Reading

War & Peace & Judaism

Robert Eisen was walking to campus on 9/11 when he saw a dark cloud above the Pentagon. Alick Isaacs fought for the IDF in Lebanon. Their experiences prompted them to rethink peace and Judaism.

In My Country There Is Problem

Through this new book we get a disturbing picture of how students and faculty in the self-proclaimed progressive movement have demonized and marginalized Israel, its advocates, and anyone who wishes to genuinely learn about the Jewish State.

Rov in a Time of Cholera

From limiting minyan sizes to magical amulets, a look at how one rabbi faced waves of cholera epidemics over his long 19th-century career.

No Greater Love

The Israeli music scene is bringing together world-class Israeli jazz and classic Sephardic liturgical music. Voilà!: the jazz piyyut.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In