No Greater Love

Two of the most interesting developments in the Israeli music scene over the past fifteen years have been the rise of world-class Israeli jazz and the turn to classic Sephardic piyyut (liturgical music). The remarkable New Jerusalem Orchestra (NJO) has spent the last four years bringing a serious jazz sensibility to the performance of Andalusian piyyut, and it will be performing two shows in Jerusalem this September. But the NJO also recently released a two-disc recording, Ahavat Olamim (“Eternal Love”), that is an extraordinary blend of soul and first-rate musicianship and a turning point in the development of a uniquely Jewish-Israeli culture.

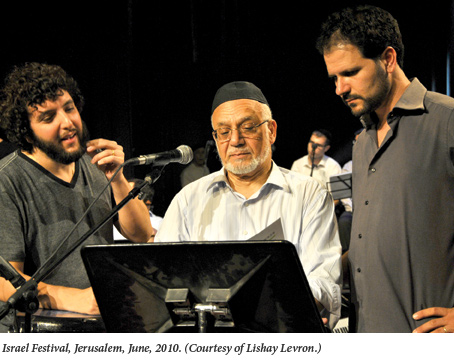

NJO’s directors, Yair Harel and Omer Avital, were part of this story before they joined forces. Harel is an accomplished percussion player and vocalist and the co-founder and editor of the popular Israeli website “An Invitation to Piyut,” while Avital is a critically acclaimed American-based jazz bassist. For Ahavat Olamim, Harel and Avital were joined by the Moroccan-born master of Andalusian piyyut, Rabbi Haim Louk, a Torah scholar and world-class vocalist with an extraordinary ability to communicate emotion through a microphone.

Harel, Avital, and Rabbi Louk were brought together by their shared love of piyyut. But they also share an antipathy for the once-powerful claim that forming an Israeli identity requires erasing all traces of the diaspora, and they are aware that they are engaged, to a certain extent, in an act of recovery. In their liner notes, Harel and Avital write, “we seek to ingather the exiles of the Jewish soul that were exiled in, of all places, the Land of Israel.” For Harel, the recovery is part of a larger Zionist vision. For Avital, it’s part of a personal-familial quest. For Rabbi Louk, the motivation in introducing piyyut to a broader audience is simply Jewish.

Harel’s dream is to cultivate from the sources of piyyut a Jewish-Israeli identity that, grounded in the multi-cultural past of the Jewish people and responsive to the cultural dynamics of Israel’s present, will be far more open and vital than what the founding fathers of Zionism left behind. A faithful student of the celebrated Israeli composer and ethnomusicologist, Andre Hajdu, Harel extended his teacher’s love of musical freedom and habitual disrespect for conventional boundaries by reaching out to Avital and offering to bring the half-Yemenite, half-Moroccan virtuoso to the 2008 piyyut festival in Jerusalem.

Avital, who was by his own account doing some soul-searching at the time, gladly accepted the offer. In high school in the mid-1980s, he and a couple of friends had turned their backs on their Israeli musical peers and started seriously digging Charlie Parker. After army service, Avital moved to New York and encountered—in jazz figures such as Billy Hart and Rashid Ali—the openness, vitality, and depth of the American jazz tradition. This encounter with a living tradition moved Avital to explore the Moroccan and Yemenite Jewish traditions that had played a peripheral role in his own secularized youth. He embarked upon an intensive study of classical Arab music, especially of the Moroccan-Andalusian variety. When Harel invited Avital to the Piyyut Festival, which would feature Rabbi Louk, Avital, who had been listening to cassette recordings of Louk, jumped at the chance to play with one of his artistic idols.

As for Rabbi Louk, he embraced the opportunity to reach a wider audience. It is difficult now to appreciate the degree to which Jewish culture that is deeply rooted in an Arab milieu was marginalized during the first decades after the founding of the state. Despite its sophisticated Mediterranean openness and long history, Andalusian piyyut was considered by the Ashkenazic elite to be music for primitives. Frustrated by the artificial limitations that Israel imposed on Sephardim and looking for place where he could practice his tolerant but deeply pious brand of Judaism, in the early 1980s Rabbi Louk moved his family to North Hollywood, where he assumed the position of communal rabbi of the Sephardic congregation Em Banim.

Rabbi Louk did not, however, stop performing piyyut. In the mid-1980s he even performed in Paris with one of the musical influences of his Moroccan youth—and a giant of Andalusian music—Abdessadeq Cheqara. Louk had absorbed Cheqara’s music by listening to him on cassette tapes, the same way that Avital had absorbed Louk (cross-cultural influence in an age of mechanical reproduction). In 2003, Louk and his wife moved back to Israel, where they found a country that was more open to non-Western Jewish culture than it had been in the past. In 2008 Harel came calling.

The trial run at the 2008 piyyut festival was a rousing success, and all the parties involved agreed that more should be done. Punch “Haim Louke Ensemble” [sic] into the search engine at YouTube and you’ll get a glimpse both of the 2008 festival and the shape of things to come. With Avital accompanying him on bass, Louk offers a Spanish-Moroccan interpretation of “Ve’Ulai” (“Perhaps”) by the great Israeli poet Rachel that only a sworn enemy of the Zionist entity could manage not to love.

After the 2008 collaboration, Harel and Avital formed the New Jerusalem Orchestra, which in short order was offered the opening slot at the Israel Festival in May 2010. Louk was invited to be the NJO’s special guest, and Ahavat Olamim is the record of the NJO’s inaugural performance.

The album is divided into eight thematic sections—Spring; Dialogue; Love; Yearning, for where? Exile; Wanderings; Fantasy; Rejoicing—and the music draws from multiple sources: from Franco-era “Flamencoesque” tunes (that were eagerly consumed by Moroccan Jews in movie houses on the far side of the straits of Gibraltar), to gospel blues. The skeleton of the music, however, remains completely traditional, with Avital adding blues harmonies and various tone colors—aside from his own upright bass there’s a four—piece string section and a three-piece brass section that includes the celebrated American tenor saxophonist Greg Tardy—to what is, at its heart, an Andalusian band, with an oud, darbuka, and kamanja, or Moroccan violin.

There are so many highlights in Ahavat Olamim that it’s difficult to decide which sections to single out for special attention. Louk says that, “Even the Ashkenazim love ‘Tzur Shecheyani,'” so that’s probably a good place to start.

“Tzur Shecheyani” is a piyyut written by one of Louk’s teachers, Rabbi David Buzaglo, a legendary 20th-century master of Moroccan piyyut who passed away in 1975. Rabbi Buzaglo adapted “Tzur Shecheyani” from the Arabic song “Ayli Hayani,” composed by Mohamed Fouiteh (1928–1996), and it appears in the section entitled “Dialogue.” But the dialogue doesn’t end there. “Tzur Shecheyani” is based on a Berber rhythm and uses an African pentatonic mode. This makes for a natural connection to the blues, which is also pentatonic. Avital draws out the blues feeling by having Greg Tardy belt out a gritty solo rich in American southern feeling that sounds remarkably natural in its context. In case you forget, however, the Arabic bridges will remind you that the music is classically Andalusian. Here, Avital is in dialogue with Rabbi Buzaglo.

A further dimension is added to “Tzur Shecheyani” by Erez Biton’s poetic, prefatory ode to Rabbi Buzaglo, subtitled, “Morning Prayer for Rabbi David Buzaglo, one of Moroccan Jewry’s Greatest Paytanim.” Biton, a Moroccan-born, contemporary Israeli poet who was blinded at age 10 when he handled a stray grenade, calls out to Rabbi David, also blind, “to come out from the corner to the stage of all stages.”

Another highlight is Rabbi Louk’s stirring rendition of “Naqdishakh,” adapted into Hebrew for the Kedusha (sanctification) prayer from the turn-of-the-20th-century Spanish opera, La Leyenda del Beso. The Hebrew piece was adapted from the original by Yitzhak Kedoshim, the conductor of Louk’s childhood choir in Morocco, and Louk remembers learning the music as a young boy who had recently lost his father.

For “Smehim Be-tzetam,” taken from the Shabbat morning prayers, Avital says that he toyed with the idea of letting Greg Tardy launch into a solo and take the orchestra to church, as it were, but at first he held himself back, worried about pushing the musical envelope too far. In the end, after all the hard work left him physically and emotionally spent, Avital decided that he was entitled to a little meshugas. Tardy’s gospel-inflected solo is one of the music’s peaks.

The spirit of Ahavat Olamim is open, driving, and optimistic. But the happy vibe shouldn’t mask NJO’s dissatisfaction with the present state of Israel’s cultural affairs. Rabbi Louk’s Jewish identity remains far deeper than his Israeli one, and while Avital’s search has reconnected him to his family’s musical traditions and he now often performs in Israel, Avital still lives in New Jersey. Even Harel, the most consciously Israeli of the bunch, considers Israel’s regnant cultural ethos to be far too constricting.

What, then, can a thoughtful Zionist take away from Ahavat Olamim, aside, that is, from deep aesthetic pleasure? In one of his classic essays, “External Freedom and Internal Slavery,” Ahad Ha-am wrote that, in exchange for being granted political rights, Western Jews were being asked to pay a price in the coin of inner servitude to Western cultural conventions. I would argue that what was true for individual Western Jews in the 19th century is true today for Israeli society as a whole.

Ahavat Olamim reminds us that, culturally and spiritually speaking, the Jewish people is not so much part of the West as the West is part of the Jewish people, in the same way that the East is part of the Jewish people. By connecting the jazz clubs of New York City to the late-night “Shirat Ha-bakashot” (“Songs of Seeking” in Edwin Seroussi’s wonderful translation) sung in Morocco, to present-day Jerusalem, Ahavat Olamim helps expand the possibilities of Jewish-Israeli identity.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

President Grant and the Chabadnik

In 1869, President Grant received an unexpected visitor at the White House: Haim Zvi Sneersohn, a flamboyant and eccentric Chabad emmisary from Jerusalem. Bedecked in what The New York Times described as an "Oriental costume" consisting of a "rich robe of silk, a white damask surplice, a fez, and a splendid Persian shawl fastened about his waist," he strode self-confidently toward the president. Grant instinctively rose to greet him.

Between Frankfurt and Jerusalem: Scholem, Adorno, and the Fate of the Sacred

When the philosopher Theodor Adorno met Gershom Scholem, he thought that he “gave the impression of a Bedouin prince.” Their lifetime of letters orbits their shared love of their brilliant, doomed friend Walter Benjamin.

Leviticus on the Fourth of July

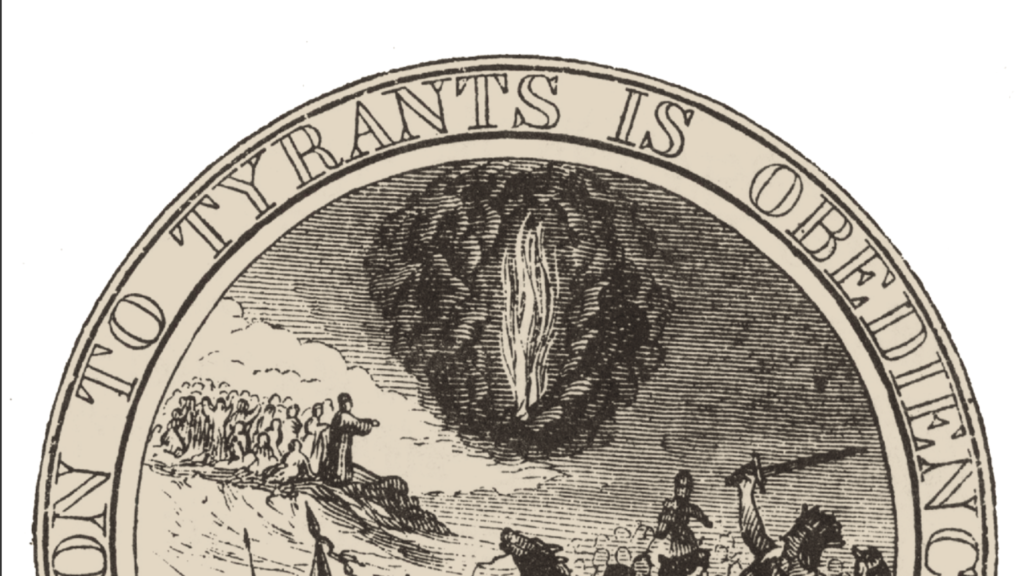

Biblical narratives and imagery have played a surprisingly large, even outsized, role in the formation of the American national consciousness and institutions.

Hebraic America

When Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin sat down to design the Great Seal of the United States they both turned to the Bible.

Julian Tepper

I have many reasons for being happy that Aryeh is my son.

One of those reasons is his affinity to Piyyut, through which I have come to like it very much.

And Aryeh's West-connected jazz appreciation background, coupled with his closeness to the Sephardi Jewish culture and liturgy, makes his recognition of the genius of Piyyyut quite understandable. j