Rov in a Time of Cholera

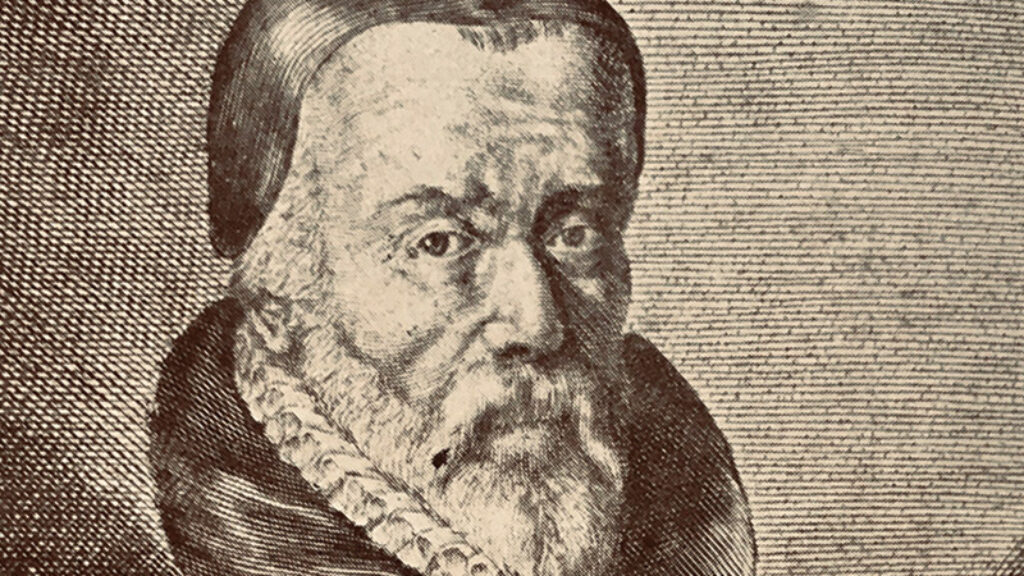

Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmacher was about 35 years old, serving the community of Pleschen (today Pleszew, Poland) in his first rabbinic appointment when cholera hit. This was the summer of 1831, and the second of five cholera pandemics to strike during the 19th century. After its appearance in India, the disease spread west eventually from Russia to Poland and then to Prussia. It soon moved on to the British Isles and North America, killing hundreds of thousands of people.

As the disease tore through his community, Rabbi Guttmacher wrote to his teacher, Rabbi Akiva Eger, the rabbi of Posen (Poznan). It is hard to overestimate the esteem in which the rabbinic world holds Rabbi Eger to this day. His glosses adorn every page of the standard editions of the Talmud and Shulchan Arukh, and his Talmudic discussions and halakhic rulings are masterpieces of analysis. Yet, when his disciple in Pleschen asked how to address the new scourge of cholera, Rabbi Akiva Eger answered with simple, practical advice. His letter, of course, reflects 19th-century medical information, but it has rightly been making the rounds on Israeli social media and #FrumTwitter during the COVID-19 pandemic as an example of rabbinic leadership during a crisis:

With the help of God, may He be blessed. Monday of the Torah reading of “Nitzavim,” 5531, Posen. . . . To Rabbi Eliyahu . . . the head of the rabbinical court . . . of the holy community of Pleschen:

I have received your letter. Regarding prayer in the synagogue, in my view it is truly not right to congregate in a tight space. However, it is possible to pray in small groups . . . of about 15 men…starting from the first light . . . and the same in the afternoon. After prayers in the mornings and evenings, recite some chapters of Psalms of your choice, followed by [specific petitionary prayers] . . . and mention therein his Majesty the King, his offspring, his officers, and all who dwell in his land. Every morning and evening recite . . . the entire passage concerning the incense . . . Make sure that no more than the aforementioned number of people squeeze in, perhaps by posting a policeman there. . . .

Protect yourselves from the cold; everyone should wear a flannel cloth around their waist; don’t eat bad foods, especially pickles; limit the eating of fruit and fish and the drinking of beer. Do not overeat; it is better to eat small quantities frequently. Stay clean; do not leave dirt and grime in the house. Change into clean, freshly laundered clothes several times a week. Do not be anxious; keep away from nervousness. Do not walk in the city’s air at night; in the afternoon, while the sun is shining, it is good to walk in the country to get fresh air; open windows in the morning so that air can enter the rooms. Do not leave home on an empty stomach; eat some mustard seed on an empty stomach and take some oak bark. Draw some water and wash your hands and face in the morning. Several times, drizzle some good, strong vinegar mixed with rosewater in the rooms.

As John Snow famously discovered a quarter-century later, cholera was spread by contaminated water (and pickles and beer were among the safest foods), but Rabbi Akiva Eger’s medical advice was the prevailing wisdom of his time and place. For instance, it was believed that abdominal chilling made one more susceptible to cholera, and the flannel “cholera belt” he prescribes was even included in army kits of the time.

Around the same time, Rabbi Eger issued a ruling that would change Ashkenazi synagogue practice forever. The pandemic produced so many mourners that the longstanding custom of rotating the recitation of Kaddish would have left each mourner with few opportunities to recite the prayer for his deceased parents. So, for that year, Rabbi Eger allowed multiple mourners to recite Kaddish simultaneously. That one-time exception has become the norm.

By the time cholera swept through the region again, Rabbi Akiva Eger had died, and Rabbi Guttmacher, now the rabbi of Greidetz (Grätz, today Grodzisk Wielkopolski), was the person other rabbis turned to for guidance. In the fall of 1852, he was presented with a dilemma: There were too many corpses piled up for the local Jewish burial society to perform tahara—the ritual cleansing and preparing a Jewish body for burial—and sew enough shrouds to meet the demand. Could they enlist the help of non-Jews in this endeavor? If need be, could they dispense with the rituals altogether and bury the unpurified bodies in regular clothing? Rabbi Guttmacher responded by prioritizing the various practices and outlining which could be dispensed with most easily when necessary. He ultimately concluded, however, that if there was really no choice, it was permissible to bury a body with a symbolic shroud over plain clothes, and without performing a tahara.

Alongside his primary occupation as a town rabbi and an address for the questions of other rabbis, Rabbi Guttmacher was among the early religious proto-Zionists, who raised funds and awareness in Europe for institutions and projects in the Holy Land. When cholera broke out in Jerusalem during the holiday of Sukkot in 1865, Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi Meir Auerbach wrote a letter to Rabbi Guttmacher describing the spread of the disease and the gut-wrenching details of the death of Rabbi Nachum Lewi of Szadek, one of Jerusalem’s sages. He then expressed his gratitude for a recent contribution to Jerusalem’s Polish community and indirectly asked him for more. A tzedaka receipt sent by Rabbi Auerbach to Rabbi Guttmacher dated a year later shows that Guttmacher continued to support the community.

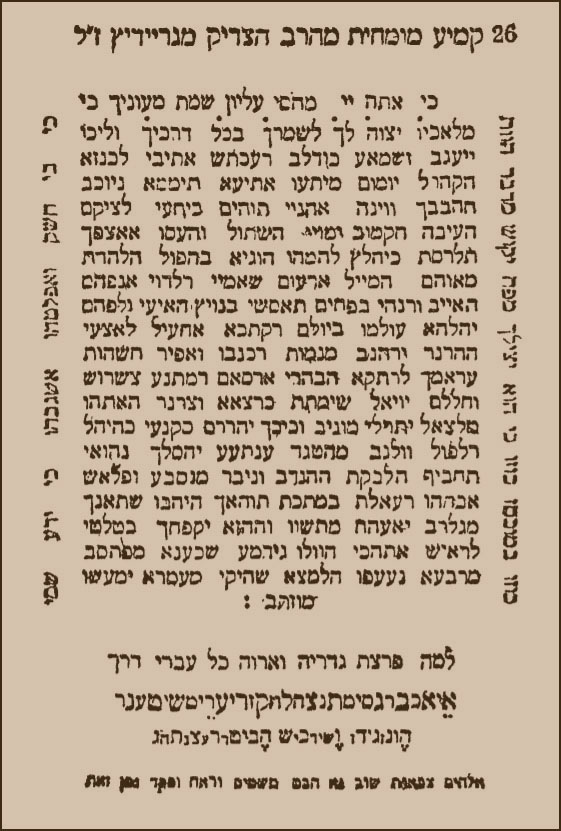

A small, undated manual containing prayers, practices, and charms to ward off plague and other forms of disaster was printed not long after Rabbi Guttmacher’s death in 1874. The main part of the booklet consists of an account of the bringing of the incense in the ancient Temple in Jerusalem. In Numbers 17:12-13, the High Priest Aaron burns incense to protect the living from a plague ravaging the Israelite encampment; the Talmud states that the antiplague properties of the incense were a secret that the Angel of Death told Moses before his return to humankind after receiving the Torah. Like so many other Temple rituals, once Jews could no longer perform them, recitation of descriptive passages took their place. So, as we saw in Rabbi Eger’s letter, the incense loomed large in Jewish attempts to ward off plague.

This manual contains other measures for when pestilence rages. Commonsense instructions, like “cleanse every room in the house, and especially outhouses, of all muck, filth, and foul odor,” appear alongside directives to place white onions, garlic, and certain types of mushroom in every window. The manual also contains several amulets, including an “expert amulet from the rabbi, the tzaddik of Greidetz [Rabbi Guttmacher], of blessed memory.” This amulet, the reader is told, was “an amazing protection against that disease,” that is, cholera during the fourth cholera pandemic:

by the wonder of our generation, the tzaddik R. Eliyahu, of blessed memory, from Greidetz, who printed them himself in 5627 (1866-7) and sent them to every boundary of Israel, and the plague then ceased from upon Israel.

This brings us to a unique aspect of Rabbi Guttmacher’s career: his reputation as a non-Hasidic tzaddik, mystic, and miracle worker.

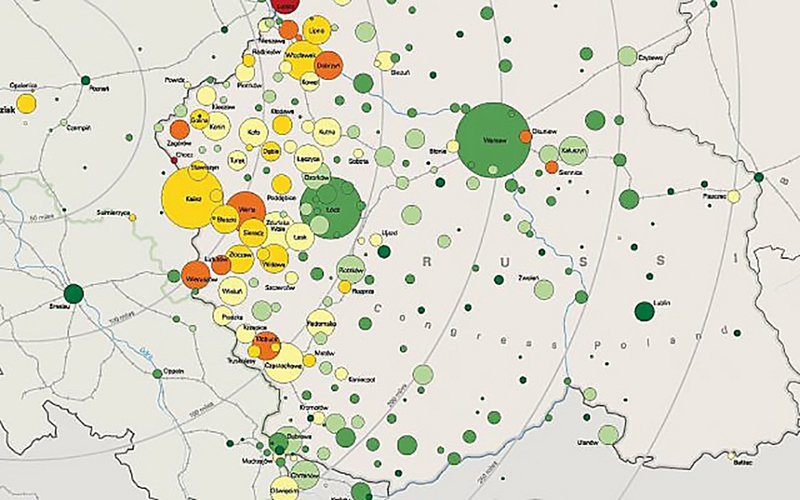

In his later years, thanks to his reputation as a miracle worker, Rabbi Guttmacher received thousands of personal petitions (kvitlekh), mainly from across the border, in Russian-controlled Poland. Glenn Dynner (see his “Brief Kvetches: Notes to a 19th-Century Miracle Worker,” Summer 2014) and Marcin Wodzinski have mined the extant petitions for a wealth of information on all facets of Jewish life in the 1870s. One such kvitel was submitted to Rabbi Guttmacher by a Krakow couple whose 15-month-old son, Avigdor Kalonymus, was suffering from an extended bout of “kholi ra” (evil disease), a Hebrew term that played on the phonetic similarity to “cholera.”

As the novel coronavirus continues to spread, we are witnessing firsthand how crucial the responses of religious leaders can be. Their behavior communicates—or fails to communicate— the gravity of the situation to their flocks. Whether they flout directives or attempt to fill the vacuum created by insufficient action by the authorities, the effects of their actions will be measured in lives. They must give comfort and hope, address the spiritual and material needs of those suffering, and decide when the needs of the hour require the disruption of sacred routines. Jewish history has known suffering and can provide today’s leaders with many role models, but perhaps none as wide ranging and well documented as Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmacher, a rabbi—a rav—in a time of cholera.

Suggested Reading

The Sephardic Mystique

In the late 18th century, an ardor for ancient Greek art and literature swept through German letters. German Jews were not immune, yet during the same period, they also devoted themselves to recovering the linguistic, artistic, and literary heritage of medieval Sephardic Jewry.

From King James to Koren

The new Koren Tanakh smoothly addresses some thorny questions of biblical translation, including this one: Are there dolphins in the Torah?

Romania!

“I Do Not Care if We Go Down in History as Barbarians” is a reenactment; the quotation marks are part of its title, suggesting just how meta this film becomes. It steps back one more level into the minds of the people doing the reenacting.

Pancho Villa and the Star of David Men

When the Young Men's Christian Association began offering wholesome recreation to soldiers in 1916, Jewish leaders were as as worried about evangelism as they were about bars and bordellos.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In