Eight Families and the 18 Percent

I suppose I am just one of those old-fashioned Conservative rabbis of yesteryear who, according to Daniel Gordis, once were “reasonably conversant in classical Jewish texts and able to teach them to their flocks.” (The implication that phrase of his carries about today’s rabbis, many of whom, like Rabbi Gordis, were my students, is no doubt deliberate.) One of those classical texts (in the Talmud, Bava Kamma 92b) offers the homely but well-placed advice that when one has drunk from a well, one should not later be found throwing clods of earth into it, a teaching that somehow came to mind when I read Gordis’ eulogy for the Conservative Movement.

He says that “the numbers are in, and they are devastating,” because, among other things, they seem to indicate a precipitous drop in the number of survey respondents asserting an affiliation with Conservative Judaism. So first, a very general observation: It is peculiar for someone who is aware of, and speaking for, Jewish tradition to argue that smaller numbers mean lessened potency and fitness for survival. The fallaciousness of such an assumption has, of course, been demonstrated again and again throughout our people’s history. (More on this further on.)

I am a congregational rabbi, and so it is not for me to offer an unbiased assessment of the vitality of Jewish learning, worship, spiritual journeying, and activism that exists in communities such as mine. We are by no means unusual in the Conservative world. But it is a curious cultural habit that we have developed that has us getting our primary evidence from survey data rather than from “looking out of the study window” and observing what is actually happening around us.

So let’s ask ourselves: Do the Pew Research Center numbers even convey an unequivocal tale? Not if one keeps in mind the complicated and fluid condition of American Jewry today. Today’s landscape includes all manner of inventive Jewish study and worship communities dotting the country, quite apart from the established congregations that hold denominational affiliations. The young (and not so young) Jews of these creative communities can hardly be expected to answer a polling question about movement affiliation by identifying with a conventional label. The very enterprise exemplified by “independent minyanim” and similar young “startups” is rooted in spiritual exploration beyond those labels. But it does not take intense investigation to reveal that this spectral phenomenon has three familiar features: a desire for engagement with tradition, a deep respect for and commitment to Jewish practice that is balanced with an openness to redefining its limits (gender egalitarianism, the inclusion of more than one sexuality, liturgical creativity, and the incorporation of concerns with justice into the definitions of ritual fitness), and a vision of Jewish learning that embraces our received canon first and foremost, but is not closed to other traditions, new conceptions of the divine and the critical rigors of scholarship.

In other words, the new minyanim and communities of study and practice, which are arguably the most vital new development on the American Jewish religious scene, share a great deal with the classical ideology of Conservative Judaism. It is the same ideology that attracted people like me to the movement years ago, although I had been educated in an Orthodox yeshiva and had contentedly followed that path through my college years.

“Conservative Judaism is today the denominational home of only 18 percent of Jews.” What this observation of Gordis fails to note is that 30 percent of Jews claim no denominational affiliation at all, and of those only 3 percent self-describe as “not practicing,” “atheist,” or “agnostic.”.In other words, 27 percent of American Jews (described in Pew terms as “just Jewish”) are neither non-practicing, nor atheist, nor willing to espouse a denominational loyalty. Is it at all a stretch to imagine that a significant portion of this 27 percent can be found among those in these inspired and imaginative communities? Or that among them are many young Jews who are pursuing the search for their own Jewish authenticity with the very tools that Conservative Judaism fashioned and that many of them no doubt learned in Conservative institutions? And is it at all surprising that they would be among the 41 percent of Jews ages 18 to 29 who (currently) eschew a denominational label? Indeed, Gordis himself seems to decline to give himself such a label; instead, he coyly says that he has “meandered” to “a different Jewish community.” Has he considered that there might be many others whose meanderings do not signify surrender, or lack of seriousness?

Gordis’ critiques of his erstwhile religious home are also hard to follow. At one point, he condemns the movement for “abandoning a commitment to Jewish substance,” but he also derides its historical concern for halakhic discourse. What does he suggest movement leaders should have done instead? It is to have preached Jewish solidarity as the way to save us from merely being “part of an undifferentiated human mass” and to have instilled the “instinct that our people . . . still has something to say.” Is this urge to belong more substantive than halakhic reasoning?

Similarly, although he scoffs at the relevance and importance of the question of “how one could speak of revelation in an era of biblical criticism,” this does not prevent him from leveling the exact opposite critique later on:

Looming unasked in Conservative circles is the following question: Can one create a community committed to the rigors of Jewish traditional living without a literal (read Orthodox) notion of revelation at its core?

Unasked by whom? Not, certainly, by his teachers, or by rabbis like myself. When criticism comes from both sides like this, it is almost always a sign of censure for the sake of censure.

But back, finally, to the question of the relevance of numbers. My own intellectual father, Gordis’ uncle Rabbi Gerson Cohen, used to love to ask: “You know about that Golden Age of Spanish Jewry?” and then he would pause, deadpan, before continuing, “It was eight families.” We no longer organize ourselves primarily around clans. But there are cadres and communities that continue to live out and develop the kind of moral and spiritual engagement with tradition that Conservative Judaism came into the world to cultivate. Moreover, there are more than enough of them to ensure that this noble enterprise can prevail and even eventuate in newly defined and robust movement institutions.

What Conservative Judaism has stood for continues to represent the ideal mode of engaging Jewish tradition to far more than the 18 percent to whom Gordis and other eulogizers love to refer. Perhaps the ultimate irony is that Rabbi Gordis actually comes from a modern version of one of those “eight families” whose vision transcends polls and whose patience and tenaciousness change the world. More’s the pity that he has allowed himself to “meander” away.

Editor’s Note: Daniel Gordis replies to his critics and outlines his positive vision for the future.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

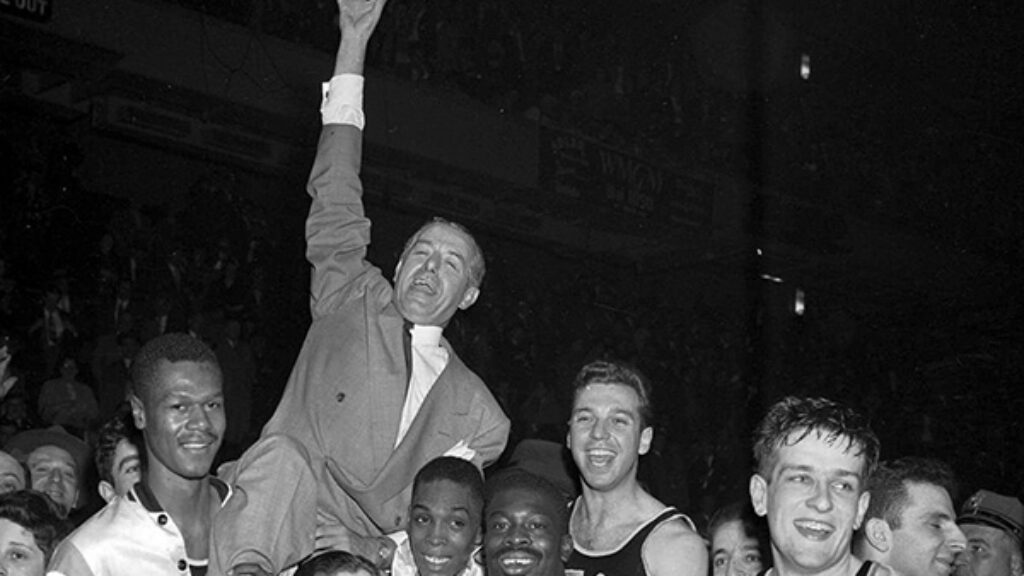

The Fix Was In

The 1951 basketball game that pitted CCNY, which fielded blacks and Jews, against the all-white University of Kentucky seemed less a meeting of schools than a clash of civilizations: old versus new, South versus North, prejudice versus tolerance.

The Audacity of Faith

The career and life of Yehuda Amital—unconventional, unpredictable, and free of clichés.

A Tale of Two Exiles

What did a seditious Sicilian duchess and the heretical son of a chief rabbi have to do with the beginnings of French antisemitism?

A Very Jewish Encounter

The text is full of underlining, circled words or phrases, arrows, careful cross references, and copious comments in Yiddish, English, Spanish, and Hebrew. It’s what my students at Ohio State might call an “extreme reading.”

rubyz

The chief problem concerning Jewish identification has little to do with the ideology of a particular stream (such as Conservative), but rather with the matter of what Ms. Caroline Glick and Dr. Yoram Hazoni call 'Jewish literacy.' Far too many Jews who consider themselves 'traditional' and even bother to going to a synagogue occasionally are much more obsessed with the trappings of the cultural and ethnic aspects of Judaism than they are with knowledge of Jewish Scripture, which is the very key to one's fulfillment as a Jew - regardless of which ideological path they may eventually choose.

Moishgil

Yasher koach Rav. Thank you for reminding Rabbi Gordis and the Jewish community that numbers organized into grids and tables can't tell the whole story. The validity of the ideas, philosophy and theology advanced my Conservative Judaism was never really validated by the number of affiliates of Conservative Synagogue which always had more to do with array of variables from geography to sentimentality. The notion that intellectual honesty and critical study has to be set aside for the sake of perpetuating myths about the origins of laws and lore is too cynical to be worthy of recognition. Halachic Judaism that is equally committed to practice as to critical study has, does and will continue to flourish in homes, schools and synagogues of the Jewish world regardless of the labels demographers feel compelled to use for their studies.

charles.hoffman.cpa

R Tucker is certainly one of the true lights of the movement combining an exemplary career as educator, scholar, and community leader. And all the while, the institutions with which he was affiliated were supported and sustained by the wealth of the general American Jewish community which paid high dues to his synagogue, made significant donations to JTS, and pumped fortunes into programs, events, and conferences which he either lead or was showcased in.

And when the American Jewish community's affinity to the Conservative movement wanes, then there will still be scholars, but nobody will support them; there will be pulpits, but they'll face empty pews; and the conferences will be gone for lack of participants to cover the costs of the resident scholars' rooms and transportation.

While R Tucker alludes to the so-called gang of 8 of classic Spanish Jewish culture, he ignores the fact that their wealth sustained them; they could afford to philosophize on their families' fortunes; and they didn't have to pay the mortgages on a whole collection of massive suburban edifices with parking lots to pave, auditoriums to heat and air-condition, and rabbis emeritus to whom they still owed pension and health benefits.

If that next generation of Jews fail to sign up their kids for Hebrew School, join the local Conservative Synagogue, and respond to the Yom Kippur appeal, the JTS appeal, the Youth Outreach appeal, and the rest of the fund-raising efforts that sustained his movement, then the edifice which was built over the past 75 years will face the same financial future as Detroit.

Solomon Schachter

Where is the interest in Halacha in any way, shape or form within the Conservative movement? Growing up as the son of a Conservative Rabbi, I knew that virtually all the active members of the congregation and it was clear that the only families who kept Shabbat or kosher were those with European backgrounds.

I knew Rabbi Tucker's predecessor, and his congregation. There were relatively few members who observed the mitzvot in anything that remotely resembling a halachic manner. In the decades since Rabbi Tucker assumed the leadership of his synagogue, how many homes has he kashered? How many of his congregants attend weekday services or study Torah on a daily basis? This is not to cast aspersions on Rabbi Tucker. Rather, I suspect his results are little different than his peers.

The failure of the Conservative movement has been its inability to get its members to practice what it preaches. Counting on Havurot and kehillot whose membership seek spiritually, often without halachic commitment, to replace the European membership of two generations ago is grasping at a pretty thin reed upon which to bet on its future.

charles.hoffman.cpa

if you feel compelled to mix metaphors, please follow the directions on the container

SDK

Many of the people in traditional egalitarian minyanim are the daughters of Conservative rabbis. Their sons, it seems, are elsewhere.

This difference does suggest that it's not just the lack of halachic observance that drives the children of Conservative rabbis away from the hypocrisy and the isolation of their youth. It's also that Orthodoxy provides a comfortable home for those who can transition there without losing things that really matter to them. It's painful to give up being a Jew (as in "a Jew lays tefillin every morning") in order to become a woman (as in "a woman is acquired in three ways and acquires herself in two").

When ChaBad sends shilchim to be the only Orthodox families in Kiev or Reykjavík or Muncie, Ind. they also make a plan to educate their children. The shlichim have large families and they teach their children, every day, that they are on a mission.

Conservative Jewish rabbis aren't willing to go that far and the result is that their kids have all of the restrictions and none of the benefits of observant life. Maybe if JTS opened a branch in Oklahoma, it would also have a plan to support the only non-Orthodox shomer shabbat family in Oklahoma.

It sucks to be the kid who can't eat anywhere, the kid who can't do anything, the kid who has to get up early and pray. But there are lots of things that are right and good in the world that are also hard and unpopular.

The more of us who do those hard and unpopular things, the easier it will be on our kids. Some of us are still rooting for that option and we intend to keep living it, whether we are 18%, 40% or 4% of the American Jewish population.