Could It Have Happened Here? The Implausible Plotting of The Plot Against America

Watching HBO’s excellent production of Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, I felt some of the same uneasiness I felt 15 years ago when I read the dystopian novel on which it is based. Now, as then, the first thing that bothered me was the figure of Rabbi Bengelsdorf, a South Carolina-born Conservative rabbi who appears first as an ardent supporter of the antisemitic Charles Lindbergh’s 1940 campaign for the presidency and then as an enthusiastic promoter of the Office of American Absorption, a sinister government program to remove Jews from the East Coast to the hinterland and thereby promote their more rapid assimilation.

How plausible is such a rabbi? Was there a Conservative rabbi in the United States in 1940 who bore even a remote resemblance to Bengelsdorf? Perhaps one could imagine a Reform rabbi, of the kind who in 1942 founded the virulently anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism, taking such a collaborationist stance, but a Conservative one who, as the miniseries (but not the novel) shows, led his congregation’s prayers in Hebrew? The Conservative rabbinate at the time was divided between the traditionalists influenced by Louis Finkelstein, who had just been appointed chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary and the radicals who were under the sway of Mordecai Kaplan. All of them would have been appalled at the idea of transferring masses of Jews to the Midwest to make them more American and less Jewish.

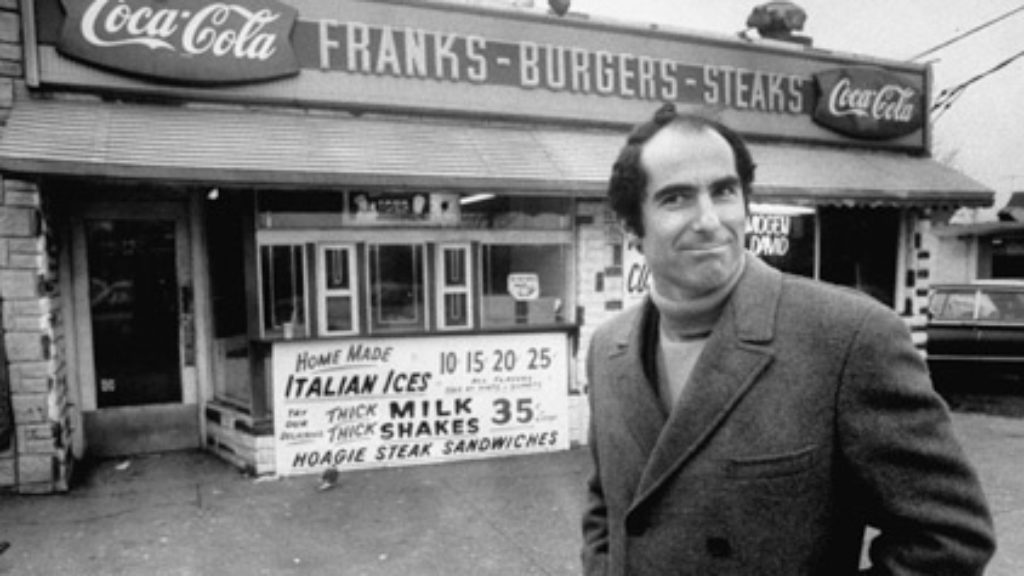

I know we’re dealing with fiction here, and some people will brush off such concerns by saying that a novelist can invent whatever and whomever he wants. That answer won’t work here, however, because Roth himself clearly thought otherwise. In an essay that he wrote for the New York Times shortly before The Plot Against America was published, he announced that his intention in the novel was to “alter the historical reality by making Lindbergh America’s 33rd president, while keeping everything else as close to factual truth as I could.” He didn’t do that in the case of Rabbi Bengelsdorf. Why not? Roth, who didn’t care a whit about theology, may not have thought about the matter at all. Or it may be just another example of his well-attested disdain for almost all rabbis. In any case, the character of Rabbi Bengelsdorf (played to oily perfection by John Turturro) rings historically false.

With respect to Lindbergh, Roth stressed his general adherence to the historical record prior to 1940, and he was justified in doing so. Charles Lindbergh was exactly the kind of isolationist antisemite that Roth depicts in his novel. The book deviates from history not by transforming a real-life hero into a villain but by placing Lindbergh in a spot where he never actually set foot: the tumultuous 1940 Republican convention, where his unexpected appearance on the scene leads to his surprise nomination. The rest of the story all follows from this one imaginative twist, but it does so more or less plausibly. Each of the historical figures who appear in the novel, as Roth insisted, “might well have done or said something very like what I have him or her doing of saying.” I see little reason to challenge this assertion (though it’s hard to believe that Hitler’s foreign minister, Ribbentrop, would have danced in public with a Jewess in 1942, as he does here).

What bothers me is Roth’s depiction not of specific individuals but of the American people as a whole, painting them as a very ready carrier of profound antisemitism. Of course, Roth had a historical leg to stand on. There was a great deal of discrimination against American Jews in the 1930s, and Jewish immigration was widely and tragically opposed. I know about Father Coughlin, the German-American Bund, and the rest. But I have my doubts about whether an openly antisemitic candidate could have won the presidency in 1940, as Lindbergh does in The Plot Against America.

Roth himself didn’t think it was far-fetched to imagine Lindbergh, “with his unshakeable isolationist convictions . . . depriving Roosevelt of a third term,” in 1940. (He got the idea from an aside in Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s autobiography.) Maybe not, given the strength of the American people’s opposition at this point to getting entangled in World War II. But what if, in addition to being an isolationist, Lindbergh had been an outspokenly antisemitic candidate? Roth makes him one in the novel by doing nothing more than moving his notorious speech at an America First rally in Des Moines vilifying America’s Jews as subversive warmongers from September 1941, when he actually gave it, back to early 1940—before the Republican convention. In doing so, Roth wrote, he didn’t “alter its content or impact.”

True, at least with respect to the speech’s content, but how was it received, in reality? As A. Scott Berg wrote in a 1998 biography that Roth probably read before he wrote his novel, Lindbergh awoke the morning after the Des Moines speech “to a Niagara of invective. Few men in American history had ever been so reviled.” Berg goes on to describe how the leaders of America First sought to minimize the damage done by Lindbergh by declaring that their organization was open “to all patriotic Americans, whatever their race, color, or creed.”

More recently, historian Susan Dunn has written that after the speech,“newspapers, columnists, politicians, and religious leaders lashed out at Lindbergh for sinning ‘against the American spirit,’ as the New York Herald Tribune put it. ‘The voice is the voice of Lindbergh, but the words are the words of Hitler,’ wrote the San Francisco Chronicle in an editorial that echoed dozens of others.” Waving a copy of Mein Kampf on the House floor, Luther Patrick, a Democrat from Alabama, exclaimed that “it sounds just like Charles A. Lindbergh.” Thomas E. Dewey, a Republican presidential contender in 1940, branded the talk “an inexcusable abuse of the right of freedom of speech.” Another, Senator Robert Taft, “called Lindbergh’s reference to Jews as a foreign race ‘a grossly unjust attitude.’”

Lindbergh had his supporters, to be sure, including Mussolini, and the American First Committee tried to defend him against the charge of antisemitism. “But in fact,” writes Dunn, “America First never recovered from the calamity of Lindbergh’s stop in Des Moines. Some of the members of the executive and national committees resigned, major contributors bailed out, and the head of the New York chapter, John T. Flynn, branded the speech ‘stupid.’”

That’s not exactly what happens in The Plot Against America. In Roth’s fictional version of events, “the very accusations that had elicited roars of approval from Lindbergh’s Iowa audience were vigorously denounced,” to be sure, not only by liberals and Jews but “even from within the Republican Party by New York’s District Attorney Dewey and the Wall Street utilities lawyer Wendell Willkie, both potential presidential nominees.” But Roth leaves out the displeased Republican journalists and says of the America First Committee only that “the broadest-based organization leading the battle against intervention in the war” continued to support Lindbergh after the Des Moines speech, “and he remained the most popular proselytizer of its argument for neutrality.”

To make his story work, Roth had to downplay the extent to which the condemnations of Lindbergh’s speech went across the ideological board of America at the beginning of the 1940s. The HBO production distorts matters even further. It shows only Jews taking offense at Lindbergh’s words and strongly suggests that his antisemitic speech won him nothing but increased popularity among Gentiles. All of this flies in the face of the historical record, which shows that this country was not as primed in 1940 for an antisemitic leader as Roth and his adapters would have us believe it was. A speech like the one he actually gave in Des Moines in 1941 would likely have doomed the possibility of a Republican nomination for Lindbergh, let alone a successful presidential campaign.

Why does this matter? Roth himself said he wrote The Plot Against America, in part, to show that “it might have been different and might have happened here.” Fortunately, he continues, “at the moment when it should have happened, it did not happen.” Still, the argument of his novel is that it easily could have, that a majority of the American electorate might have colluded in the “plot against America.”

Dubious as this is as a historical argument, it gains a lot of strength from Ed Burns and David Simon’s brilliant production (see Janis Freedman Bellow’s earlier thoughtful review in these pages). The show is bound to reach a lot more people than Roth’s novel ever did, especially now, with HBO’s huge captive, quarantined audience. Many of these viewers will be easily convinced by the meticulous sets and great performances that Roth was right, that it very well could have happened here (I don’t even want to think about those who will believe that it did happen).

Roth’s book didn’t make a convincing case that the US was, even briefly, as bad as he believed it to have been, and neither does HBO’s miniseries. Both versions of The Plot Against America leave a deeply misleading sense of what this country was like in 1940.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

When Everything Matters

Bellow on Roth on TV.

How Many Tears?

Which played a larger role in Jewish migrations: oppression or economics?

Roth’s Roth-Centricity Was Just Fine

His Jewish women may have been flat, but he’s still worth reading.

No Joke

Roth's new novel takes surprising turns on familiar territory.

Norman Levin

In a classic example of forests and trees, Dr. Arkush's review so misses the point. He argues that the climate of 1940 America would not have supported an antisemitic Lindbergh and that many leading politicians spoke up against his views. But he ignores the furor of the exuberance of those Des Moines attendees. The larger issue is not that it did not happen; the issue is that it still could. With AK-47 militants surrounding state capitols and providing armed protection for businesses that wish to reopen in the midst of the pandemic despite governors' orders, I doubt that many of us are feeling all that secure right now. Imagine a Rush Limbaugh-supported Rand Paul, John Cornyn or Justin Amash with Trump-sponsored declarations of a stolen election. If Arkush is suggesting that it can't happen here, I invite him to visit Northern Idaho and Washington State in a yarkmulke.

Robert J Bresler

Prof. Arkush has written a superb essay. I would just add that the American First included voices from the left and the right. The right was concerned that our involvement in the war would result in big government becoming a permanent part of American life. The left, which included Western progressives like Wheeler, feared the war could end New Deal reforms and divert resources and public energy elsewhere. Ironically both sides had strong arguments, born out by history. Concern over the threat from Hitler and the Japanese militarists turned out to be a stronger one. Pearl Harbor settled the issue. Even though I am a great admirer of Philip Roth's work, I found The Plot Against America distasteful and the HBO film even more so. As Prof. Arkush reminds us, we were (and are) a better country than Roth and HBO imagine we might have been.

SIMON A ORDEVER

A rather strange insular take on the series (I have never read the book).

The lessons to be learned are not necessarily from the far right but from the anti Zionist intellectual establishment, and from inside the Jewish community itself.

Peter Beinart, Max Blumenthal, Miko Peled and Noam Chomsky all could make a convincing case for Jewish downfall as did the Conservative Rabbi Lionel Bengelsdorf of Newark in the earlier episodes.

reid

I understand Alan Arkush's historical objections to certain details in Philip Roth's novel, not least of which is his focus on a late 1930s Conservative Rabbi serving as spokesman for the anti-Jewish Lindburg administration. But Roth was not writing an alternative history by the usual rules of the genre. What I found in the novel was much more ambitious, an attempt to understand the contemporary Jewish mindset by offering up a myth of origin: a date, time and crisis. In that light, many of the jarring details are arguably intentional and essential to his artistic purpose, one of which was to thump the reader awake from time to time. But the novel is undeniably nightmarish because it looks deeply into the mindset of Roth and his generation who came of age in the later 50s-early 60s and saw an America ripe with fascist potential. Bengelsdorf's portrayal, it seems to me, owes more to Roth's reflections on the alesteste juden, the ghetto puppets used by the Nazis, whether well-intentioned, corrupt or absurd. Ordinary human vanity and fragility left them vulnerable to obsequiousness and delusions about the Jewish situation. By focusing on a Conservative Rabbi from a southern background he allows the reader to explore imaginatively that subtle line between assimilation and disloyalty. For me, the novel is one of Roth's best and the most personal because it probes into the Jewish fears that shaped him and his generation, by which I mean the Manichean liberalism, the identification of Republicans with Nazis and the conviction that America is perpetually one election away from fascism. All of these play a role in defining the Post WWII generation, their political expression and, more importantly, their inner life. As for the dramatization, well, it was contemporary entertainment but it achieved precisely the opposite of what Roth's artistry aimed to do. It drilled down on the fears of the moment in a way that permitted no disbelief, just horror and uncertainty that is the stuff of the present moment, though I must say the interiors, lighting, costuming, speech and manners were very compelling for those of us of a certain age.

Rabbi Arthur Waskow

Roth wrote the book in the midst of the Bush Administration, the horrendous attacks of 9/11, and the emergence of anti-Muslim behavior and ideology. I wonder whether he knew "The Plot" would have been impossible in 1940 but saw something like it emerging in the future -- as indeed has become the case with the election of Trump. Of course, Trump's racist orientation has been focused far more on brown-skinned Spanish-speakers and Muslims than Jews -- much more vulnerable than Jews now or even in 1940. But the "It Can't Happen Here" mode not as possible history but as possible future is almost certainly what he was about.

There has been very little discussion of a crucial theme of Roth's book Perhaps it is not central in the TV series, which I have not seen. But I reread the book just a few weeks ago, and I thought its central theme was whar very BIG world events could do to shatter a family. Roth spends much more time on "his" Newark family that even the BIG events. The unlikely rabbi may have been important to Roth mostly for his agency in persuading two Roths to break with their family to support Lindbergh.

The "dea ex machina" solution near the end when Ann Morrow Lindbergh saves the country from outright fascism acted out by the VP seems weird to me. It feels to me as if Roth got bored (or frightened?) by his fable and needed a way to get back to the America of history with an FDR third-term, entry into WW II, etc