Jeremiah’s Dilemma: A Response to Hillel Halkin

There is not much I can disagree with in Hillel Halkin’s portrait of the present cultural and political moment in the State of Israel. His despair captures the mood of many in the country who, having experienced the most diverse governing coalition in Israeli history, now face the possibility that the new government coalition, whose components Halkin accurately describes, represents the shape of things to come for the foreseeable future.

Where I part ways with Halkin is in the final section of his essay. I am nearly forty years younger than Halkin; I hope that his line to his friend, “Neither of us will live to see the end of this,” will not apply to me, and perhaps for precisely this reason, I do not permit myself to lose hope. For me, the question is: where can I turn to find hope that the State of Israel will not continue down the path that Halkin prophesies?

Halkin writes to his friend, “You put the blame on Zionism, and I put it on Judaism, of whose fantasies and delusions Zionism sought to cure us only to become infected with them itself.” Quoting Yehuda Leib Gordon, Halkin conjures Zedekiah as the embodiment of the Zionist ethos and Jeremiah as the embodiment of Judaism.

Yet Halkin ought to know, especially in his doomsaying mode, that he is not being quite fair to Jeremiah—or to Judaism. It was Jeremiah who walked the streets of ancient Jerusalem, wearing an iron yoke to symbolize his warning that the Kingdom of Judah must submit to Nebuchadnezzar or else suffer sword, famine, and pestilence. In that very passage (Jeremiah 27: 4-6), Jeremiah utters words that would be anathema to the Israeli Right, and perhaps even much of the Left:

Thus said the LORD of Hosts, the God of Israel… “It is I who made the earth, and the men and beasts who are on the earth, by My great might and My outstretched arm; and I give it to whomever I deem proper. I herewith deliver all these lands to My servant, King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon. . . .

The books of Leviticus and Deuteronomy state very clearly that the Land of Israel is no unconditional birthright, but that it vomits out those who do not meet its standards. For centuries before Zionism, there was an ethos of reverence toward the land and a fear of failing to live up to it. Better to be a sinner in exile than in God’s palace. Jeremiah did not face the dilemma that faced Halkin and his friend—whether to stay or to go—but rather a question that originates in a very different mindset: how long will the land itself suffer us?

It was the Zionist movement and its precursors that turned this ethos on its head, that sought to “cure” Jews—in Halkin’s words—of Judaism by making us a “normal people.”

This brings me to the particular moment during the recent election cycle that caused my concerns to peak: when I first saw the campaign slogan of Otzmah Yehudit (Jewish Power), headed by Itamar Ben-Gvir, plastered on a billboard. The slogan was “Mi po ba’alei ha-bayit?” Who are the owners here? Who are the landlords? The unstated answer was that we, the Jews, are masters of this house. Not the Palestinians, but also not God. God’s word through Jeremiah, “I give it to whomever I deem proper,” did not in, factor even though the campaign season began at the tail end of shmita, the Sabbatical year during which we are commanded to leave the soil fallow in acknowledgment that the land is God’s, and that we are but migrants residing on His land.

Did Smotrich and Ben-Gvir inherit this obsession with ownership and control from Jeremiah, who counseled submission to Babylon, or rather from Zedekiah, who refused to cede any of Judah’s autonomy?

Thus I contend not that Zionism has been infected with Judaism, but that Judaism has been infected with Zionism—or, more delicately, that the manifestations of Zionism that sought to break with the Jewish past have penetrated, and distorted, certain strains of the Jewish religion. Gone is any sense of humility, sanctity, and reverence toward the soil of this land. Instead, the land is viewed as a possession, like any other, and the Torah merely as the deed to it. Its people aspire to be like any other, and therefore seek to project its power and sovereignty over anyone who dares challenge its possession.

It is precisely because I see such slogans, and the movements they represent, as a patent rejection of the Torah’s attitude toward the land that I cannot but believe that Judaism (and perhaps even religious Zionism) will eventually disabuse themselves of them. How long they may endure before they burn themselves out, I cannot foretell. But I hope I live to see the end of them.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

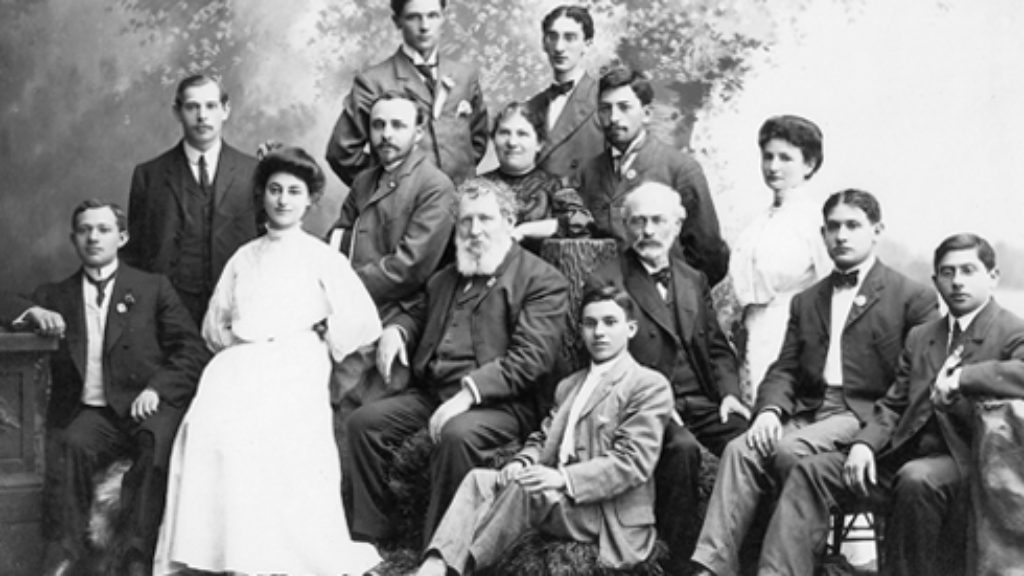

Schechter’s Seminary

Solomon Schechter is remembered as the founder of Conservative Judaism—but who are his religious heirs?

The Great Gaon of Italian Art

Berenson’s teacher Charles Eliot Norton dismissively dubbed Berenson's method the “ear and toenail school,” but Berenson employed the technique in his first book to great effect.

A Murder in Queens

The murder conviction of Marina Borukhova in 2008 shocked the Bukharan Jewish community of Forest Hills. But many questions remain unanswered.

Railroads and Dragon’s Teeth

During World War I, the Kaiser Germany sought to foment an Ottoman jihad by building a massive railroad—but he wasn't the only one with the scheme.

Daniel Saunders

This was exactly my response to Ben Gvir's slogan too. Unfortunately, I am not so optimistic about how quickly these attitudes will "burn themselves out" or what will be left of Israeli society by the time they do so.

Shmuel Feingold

Thank you for your fascinating perspective on the issues raised by Halkin.

Speaking as someone from Halkin's generation I would offer one observation. Whenever messianism has raised its head in Jewish history, wiser minds only prevailed after that messianism had run its destructive course. Who could stand up to Rabbi Akiba and tell him to stand down from supporting Bar Kochba before Jewish life in Judaea was destroyed? Who could stand down and tell Natan of Gaza and Shabbatai Zvi to go away until after Shabbatia had already traumatized the Jewish world with his conversion?

Similarly, which religious leader now stands up to call Ben-Gvir and Smotrich to stand down? What religious leader stated before the election that voting for their party was to reject God not to glorify Him?

When governments are dominated by persons who are true believers; by people who believe that they have been given secular power to advance God's agenda then standing up to them is akin to rejecting God's voice as heard by them.

The only people who can prevent this next tragic chapter in Jewish life are those who share your perspective and are willing to dedicate their lives to having this message become more compelling than the narrative currently in vogue among the vast majority of religious Jews.

David

We may not like it, but is the Haredim who do so.