Schechter’s Seminary

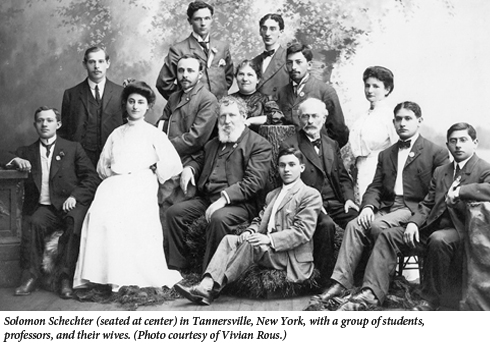

There are, no doubt, corners of ultra-Orthodox Brooklyn where people still refer to the Jewish Theological Seminary derisively as “Schechter’s Seminary,” if not in honor then at least in memory of the man who placed his stamp on Conservative Judaism’s central institution at the beginning of the 20th century. Michael Cohen has much to say about Schechter and his school in his new book about the birth of the Conservative movement, but they are not the heart of his story. As the book’s subtitle indicates, it is not on the master himself but on his disciples that Cohen has chosen to focus, and he is more concerned with what they were doing in their synagogues and rabbinical institutions than he is with what went on in the seminary that educated them to be American rabbis.

Solomon Schechter harbored big plans for American Jewry and counted on his students at JTS to implement them. When the Romanian-born and Vienna-trained rabbi who was “perhaps the foremost Jewish scholar in the world” left England for the United States in 1902, his goal, as Cohen puts it, was to help to forge “a unified American Judaism that would be both committed to tradition and also would appeal to the children of immigrants.” Unity was extremely important to him. Judaism, he insisted, is “as wide as the universe, and you must avoid every action of a sectarian or of a schismatic nature.” The Jews of America should stick together, as part of a larger “Catholic Israel,” living in accordance with rabbinic law even as they adapted it to “the ideal aspirations and religious needs of the age.”

Solomon Schechter harbored big plans for American Jewry and counted on his students at JTS to implement them. When the Romanian-born and Vienna-trained rabbi who was “perhaps the foremost Jewish scholar in the world” left England for the United States in 1902, his goal, as Cohen puts it, was to help to forge “a unified American Judaism that would be both committed to tradition and also would appeal to the children of immigrants.” Unity was extremely important to him. Judaism, he insisted, is “as wide as the universe, and you must avoid every action of a sectarian or of a schismatic nature.” The Jews of America should stick together, as part of a larger “Catholic Israel,” living in accordance with rabbinic law even as they adapted it to “the ideal aspirations and religious needs of the age.”

Schechter was indeed, as Cohen observes, “frustrated by what he saw as both the Reform movement’s rejection of tradition and “Orthodoxy’s unwillingness to modernize.” Most of his disciples were immigrants or the children of immigrants who also wanted tradition as well as change and who dismissed Reform Judaism as too alien to their sensibilities, viewing Orthodoxy as working class, European, backward, and even downright un-American. But Schechter, on principle, didn’t instruct them to start a third movement. Indeed, most of them “were forced to accept pulpits in congregations that were not particularly sympathetic to Schechter’s vision,” either because they were too traditional or not traditional enough.

Some who accepted pulpits in Orthodox synagogues found themselves locked in losing battles on behalf of the English language and “decorum.” Rabbi Louis Egelson, for instance, who took a position in a traditional Washington, D.C. synagogue, uselessly pleaded, according to his own report, “for the inclusion of some English in the prayers so that the younger people could recite some prayers.” Others, who managed to situate themselves in Reform congregations, complained to Schechter how they were reviled for their “orthodoxy.” But not that many of them succeeded in beating out the graduates of the Reform movement’s more established Hebrew Union College, who had their own professional association, in the competition for such positions.

Schechter’s “boys” needed to create a counterweight both to compete and to overcome the inherent loneliness of life in a pulpit in what Schechter himself called “struggling synagogues,” far away from one’s teachers and colleagues. It was concerns of this kind that led to the creation in 1913 of the United Synagogue of America, an organization that pointedly avoided the use of the term “conservative,” in view of Schechter’s insistence that it not constitute “the mouthpiece of a third, or conservative party independent of either tendency.”

The big tent of all those who were, in the words of the United Synagogue’s preamble, “essentially loyal to traditional Judaism” could be erected and preserved only if its inhabitants agreed to disagree about a lot of things. It was impossible, at the outset, to design a new prayer book that all could use. Nor could the United Synagogue create an authoritative board that would make binding halakhic decisions. Following the advice of Seminary scholar Louis Ginzberg, it set up a committee that would merely “advise congregations and associates of the United Synagogue in all matters pertaining to Jewish law.” As Cohen observes, this troubled “those who wanted a clearer definition of just what they stood for,” but it “held the coalition together.”

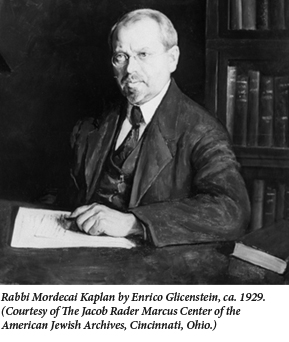

The coalition survived Schechter’s death in 1915 and remained something other than a movement. It was, instead, in Cohen’s words, “an ethnoreligious group with elastic boundaries that stretched wide enough to unify the disciples who chose to join forces to implement the vision of Solomon Schechter.” This group included traditionalists like Louis Epstein, Charles Kauvar, Max Drob, and, most famously, Louis Finkelstein, who viewed with disfavor any separation from Orthodoxy. But it also included modernists like Mordecai Kaplan, who adopted radical assumptions about theology, culture, and history. For a long time, most of these people “downplayed their fundamental differences for the sake of unity and chose to identify with the United Synagogue primarily because of their shared commitment to Solomon Schechter and his vision of a unified American Jewry.” They continued to do so even as some in their ranks pressed unsuccessfully in their new Rabbinical Assembly for the formulation of “a platform that distinguished their movement from others.”

The coalition survived Schechter’s death in 1915 and remained something other than a movement. It was, instead, in Cohen’s words, “an ethnoreligious group with elastic boundaries that stretched wide enough to unify the disciples who chose to join forces to implement the vision of Solomon Schechter.” This group included traditionalists like Louis Epstein, Charles Kauvar, Max Drob, and, most famously, Louis Finkelstein, who viewed with disfavor any separation from Orthodoxy. But it also included modernists like Mordecai Kaplan, who adopted radical assumptions about theology, culture, and history. For a long time, most of these people “downplayed their fundamental differences for the sake of unity and chose to identify with the United Synagogue primarily because of their shared commitment to Solomon Schechter and his vision of a unified American Jewry.” They continued to do so even as some in their ranks pressed unsuccessfully in their new Rabbinical Assembly for the formulation of “a platform that distinguished their movement from others.”

It was only after World War II, Cohen tells us, with the retirement and departure from the scene of most of Schechter’s direct disciples and the emergence of a new generation of rabbis, that the Conservative movement as such really began to take shape. “This new generation held a fundamentally different view of the movement than the disciples, and they redefined it in a way they hoped would distinguish it from Orthodoxy, allowing it to grow into the third movement in American Judaism.” They did so most definitively in 1950, when the Rabbinical Assembly’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards issued its famous landmark rulings that permitted the use of automobiles to drive to Sabbath services and the use of electricity to further home Sabbath observance. “Though the rulings were not binding on RA members, they did underscore the new reality that Conservative Judaism was emerging as a more unified movement that was no longer insistent upon deferring to the multifaceted Orthodox world.”

The members of this new generation believed that history was going their way. They exuded confidence that their version of Judaism was the one most suitable for Cold War America, in that it prized moderation and the power of community, even as it incorporated liberal notions of personal autonomy in religious practice. Their bullishness about the future rested on a strong faith in their reading of the past. Tradition and Change-the title of Mordecai Waxman’s 1958 collection of primary sources from the movement-defined the true Judaism.

Over the past half century, however, the Orthodoxy against which these leaders sought to define their movement has enjoyed a remarkable resurgence. Its day schools have proved to be far better incubators of knowledge and attachment to Judaism than Conservative Hebrew schools, or the Conservative day schools named after Solomon Schechter (which according to recent statistics are in decline), and even the relatively successful Ramah camps. Through these schools Orthodoxy has managed to modernize itself even as it has more effectively promulgated increasing behavioral and intellectual strictness regarding theology and practice. The Reform movement has once again re-embraced ritual and is increasingly challenging Conservative Judaism from the left. Neo-Hasidism is now in fashion for the generation that-unlike Solomon Schechter-never had the chance to rebel against the real thing.

I myself am a JTS graduate and a Conservative rabbi. Almost two decades have passed since I last occupied a pulpit, but since my family and I worship at a Conservative synagogue and my children attended the local day school named in memory of the great man himself, I remain embedded in the movement Solomon Schechter founded.

The synagogue we attend in Brookline, Massachusetts was once led by Rabbi Louis M. Epstein, whom Cohen rightly regards as one of the traditionalists, those who were unwilling to cut themselves off from a commitment to the larger totality of what they regarded as true Judaism. Yeshiva-educated in Lithuania, Epstein assumed and asserted that tradition should be the way to solve contemporary problems like that of the agunah, the woman “anchored” to a husband who has either disappeared or refused to divorce her. He invested great scholarly and spiritual labor in this effort. To his chagrin, and to the ongoing agony of the women involved, he discovered that the politics of religion precluded a broad solution across boundaries. For decades, Epstein refused to see himself as belonging to a “Conservative” group, distinct from the Orthodox, but his failure to make headway on the agunah question ultimately disabused him of this notion. In the end, he reluctantly acknowledged that his belief that law should be an instrument of necessary social and spiritual change made him a Conservative rabbi.

Attending the daily minyan in the chapel of what was once Rabbi Epstein’s synagogue, I can see all around me a rich collection of traditional texts, many of which date from his time. Not too long ago, I found between the pages of one of them a small pamphlet entitled Constitution and By-Laws of Chebra Mishna of the Congregation Kehillath Israel. Organized in 1924, this group expressed the loftiest ideals of the traditional Jewish virtue ethic: loyalty to Torah; observance of the Sabbath, festivals, and the dietary laws; the maintenance of the traditional liturgy and the Hebrew language; and the fostering of Jewish home life and religious schools “as a bond holding together the scattered communities of Israel throughout the world.” The members met for daily study of the Mishnah, weekly study of the Bible on Sabbath afternoons, and the study of the Talmud at least three times each week. Each of them needed to attend study classes at least twice a week.

Impressive as this seemed, I had to wonder: Who came? How many? How long did it last? To what extent did it define the culture of the community? And what did this tell us about Rabbi Epstein? Did the congregants that he served, and the agunot whom he tried to release, care about his halakhic commitments? And if, perhaps, a large number of them really did, how many of the members of the movement that Rabbi Epstein once served care about such things today? Is there still, in other words, on the ground, a real Conservative Judaism, or is there nothing in America other than Orthodoxy and liberalism? Michael Cohen’s new book does not dwell on such questions, but it invites us to think about them.

In an age when people continue to fret about the culture wars with fundamentalist religious fanatics on the one hand and the emptiness of liberal religion on the other, I and many others have hoped that institutions like the Jewish Theological Seminary would produce rabbis who could articulate, teach, and in today’s parlance, “community organize” a compelling third way in Jewish life. But it has mostly failed to do so. Why? Is it because of its ideological incoherence, which left it destined to be chipped away at by Reform to its left and Orthodoxy to its right? Was it the lack of true conversation between rabbis who lived inside of one intellectual realm and lay people who lived somewhere very different? Was it the mediocrity of the rabbis, who aspired to lead flocks that in large measure consisted of congregants who surpassed them in their intellectual sophistication, successful professionals who were members of what Richard Hofstadter termed the American cult of the expert, people who liked and trusted their rabbis but lacked a compelling reason to think of their pastors as their intellectual equals, much less their guides. I would have liked Cohen to spend more time with these rabbis in their synagogues, watching and analyzing the ways they tried to take notions of Catholic Israel, or the indispensability of a Judaism neither Reform nor Orthodox, and infuse them into the souls of their parishioners, then assessing the record of successes and failures.

Modernity forces all of us to deal with unending and sometimes undesirable change. Unexpected developments force us to think anew about who we are and who we want to be. We make choices. Some of them stick; some of them stick even for our children and their children. Some pass away almost as quickly as they were made. It would be sad if a worldview and a movement that combined allegiance to God and to history as Conservative Judaism has sought so strenuously to do failed to hold its own. Current realities and forebodings notwithstanding, I still hold out some hope.

Suggested Reading

On Old Stones, a Black Cat, and a New Zion

There is a legend that Prague’s Altneuschul was built on a foundation of stones from the ancient Temple in Jerusalem.

A Stolen Seat

“Good Shabbos—you’re sitting in my seat” takes on a whole new meaning when it’s your brother- in-law talking. From a Russian Jewish diary, with an introduction by Alice Nakhimovsky and Michael Beizer.

Memory Palace

“Dust comes from something. It shows something has happened, shows what has been disturbed or changed in the world. It marks time,” Edmund de Waal writes to the long-dead Moïse de Camondo.

Love in the Shadow of Death

This is a sad story, one that begins with Sarah Wildman’s discovery among the papers of her grandfather, a physician in Massachusetts, of a file of letters dating back to 1939–1942.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In