Railroads and Dragon’s Teeth

As dawn emerged on February 3, 1915, British machine guns positioned on the western bank of the Suez Canal mowed down a squadron of Ottoman sappers attempting to reach the shore. The German-led Ottoman troops vying to unseat Britain from its longtime stronghold would not recover from the barrage. They withdrew after several more hours’ fighting, never to threaten Suez again.

The battle for Suez would seem unremarkable in the scheme of World War I, if not for the fighters responsible for revealing the Ottoman position to the British: Arab Bedouins. Recruited by the Germans to bring their fabled Islamic fervor to war, the Bedouins did just that—although in word rather than deed. The Bedouin warriors prepared for battle by shouting “Allahu akbar!” so loudly that they betrayed their location to the British. Once the machine guns erupted, the bulk of their force immediately scattered.

The Bedouins’ poor showing at Suez signaled a major disappointment in the revolution they were meant to wage—a German-backed Muslim jihad against the British Empire. In a tale recounted by Sean McMeekin in The Berlin-Baghdad Express, the Germans believed that a declaration of jihad by the Ottoman Sultan-Caliph—titular head of the Islamic world—would rally Bedouin fighters and inspire rebellion among the British Empire’s 100 million Muslims. The Germans, McMeekin writes, planned to ride the resulting “wave of anti-British pan-Islamism to world power.”

But the British countered the Turko-German jihad by backing a Bedouin re

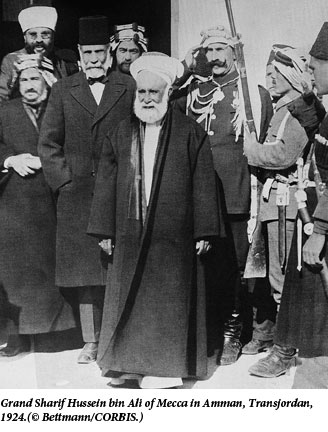

volt of their own. Shortly after the Ottoman call to jihad, they wooed Sharif Hussein bin Ali of Mecca, whose religious authority rivaled that of the Ottoman Caliph, to launch an Arab rebellion. In The Balfour Declaration, Jonathan Schneer chiefly addresses the historical forces that produced that famous document. But, like McMeekin, Schneer devotes substantial attention to European efforts to incite jihad among the Arabs—in particular, those of the British Empire. Schneer argues that the British hoped that Hussein’s uprising would allow them to retain the loyalty of their Muslim subjects while toppling the Ottoman Empire from within. Thus commenced a conflict between two Arab jihadi revolutions, backed by two Western Christian powers.

The World War I Arab uprisings are, at their core, tales of Western powers attempting to manage revolt in the Arab world. In doing so, the British and Germans misunderstood Muslim motivations, overestimated their influence, and promised their clients far more than they would, or could, ever deliver. Their follies provide powerful lessons in the limits of Western influence in the Middle East and, more significantly, the danger of inflating expectations—both in their own minds and among the Arabs whom they roused to battle.

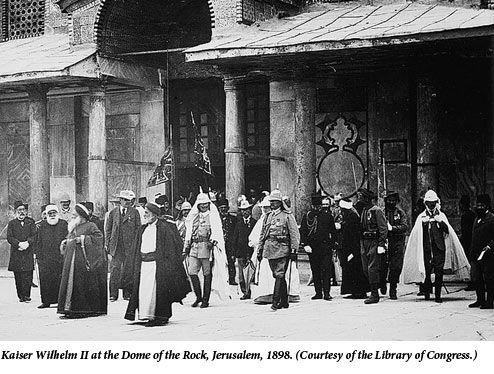

Germany’s attempt to exploit the Bedouin at Suez represented the latest manifestation of its long-running flirtation with jihad. The courtship began nearly two decades previously, when Kaiser Wilhelm II embarked on a grand tour of the Ottoman Empire. In a letter to Tsar Nicholas II following his voyage, Wilhelm declared that if he had come to Jerusalem “without any Religion at all [he] certainly would have turned Mahommetan!” Yet the Kaiser’s infatuation with Islam transcended such symbolism. In the same letter, Wilhelm instructed his royal cousin “never to forget that the Mahommetans were a tremendous card” in their machinations against Great Britain.

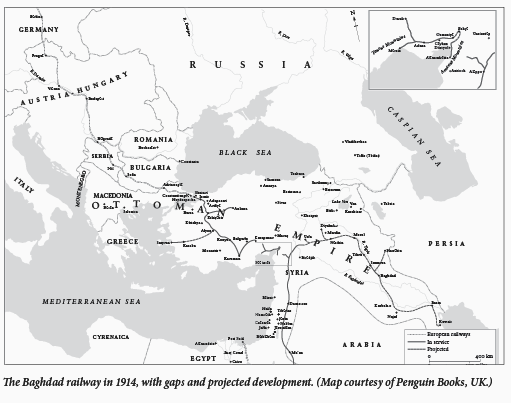

Germany began nurturing that Islamic trump card in 1903 by entering into an ambitious relationship with the Ottoman Empire to build a railway from Berlin to Baghdad. The proposed railroad would stretch thousands of miles from the European mainland to the far edge of Ottoman territory, across deserts, marshes, and mountain ranges. It posed a financial and logistical nightmare, a grand project that, in McMeekin’s words, represented the “crusading, imperial spirit” of the era.

Britain and France both attempted to secure railway contracts with the Ottomans before the Germans, but the Kaiser was well positioned to strike an agreement with the Sultan—one that would lead to a far-reaching alliance. As Germany realized, Britain, France, and Russia all ruled over millions of Muslims, whose resentment of colonial rule offered a tantalizing breeding ground for rebellion. More particularly, by the turn of the century, Ottoman relations with Britain and France had deteriorated rapidly, as the two nations encroached further and further upon the Sultan’s sovereignty. By contrast, McMeekin argues, Germany “could reasonably claim innocence in the Islamic world,” having relatively few Islamic subjects and little history with the Ottoman Empire.

The planned train would solidify this budding German-Ottoman marriage by ushering raw metals and minerals to Germany’s hungry industrial sector and potentially reviving the Ottoman Empire’s moribund eastern provinces. Perhaps just as important, the Kaiser hoped that the railroad would revitalize the weak Ottoman Caliphate by extending its reach to Mecca and Medina, and enabling it to serve as a potential locus for Muslim unity that could be harnessed against the British Empire. McMeekin’s book argues that these jihadist aspirations constituted a central plank of Germany’s war strategy. The railroad would represent the literal and figurative promise of Germany’s entreaty to the Arab and Islamic world. When the time came, Germany would utilize its success to rally Muslims across the globe against the Entente powers.

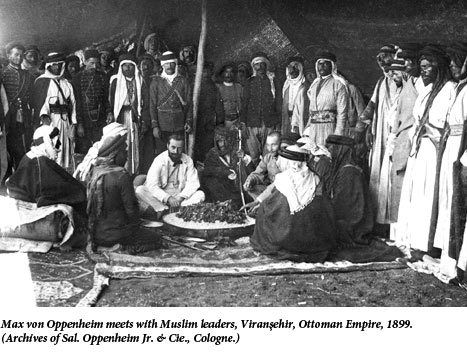

The man responsible for buttressing Islamic support for the Caliphate was Baron Max von Oppenheim, a non-Jewish heir to a Jewish banking dynasty whose life was almost an Orientalist caricature. McMeekin writes that after reading The Thousand and One Nights as a young boy, Oppenheim eventually “went native” in the Middle East. From his Cairo palace, Oppenheim ventured out to study Bedouin tribes, entertained European visitors, and kept a harem. Oppenheim’s reports on the region, which were read and admired by Lawrence of Arabia, reached the Kaiser as well, who befriended the Baron and brought him to Berlin every summer so that he could learn about his adventures.

The man responsible for buttressing Islamic support for the Caliphate was Baron Max von Oppenheim, a non-Jewish heir to a Jewish banking dynasty whose life was almost an Orientalist caricature. McMeekin writes that after reading The Thousand and One Nights as a young boy, Oppenheim eventually “went native” in the Middle East. From his Cairo palace, Oppenheim ventured out to study Bedouin tribes, entertained European visitors, and kept a harem. Oppenheim’s reports on the region, which were read and admired by Lawrence of Arabia, reached the Kaiser as well, who befriended the Baron and brought him to Berlin every summer so that he could learn about his adventures.

Oppenheim became chief of “a pan-Islamic propaganda clearing house,” at the outset of World War I, meant to spread “anti-Entente screeds” across the Islamic world. In one particularly bloodthirsty pamphlet, he wrote that Muslims “should know . . . that the Holy War has become a sacred duty and that the blood of the infidels in the Islamic lands may be shed with impunity.” He continued by urging each Muslim believer to “take upon him an oath to kill at least three or four of the ruling infidels, enemies of God, and enemies of the religion.”

From his Berlin headquarters, Oppenheim sent forth an expert company of Orientalists armed with his propaganda. They traveled from the coasts of North and East Africa to the innermost parts of Arabia and Afghanistan, recruiting Muslim leaders to rise up against the British. When the Ottoman Sultan declared global jihad on November 14, 1914—excepting Germans, Austrians, and Hungarians—Berlin waited anxiously to see whether its pan-Islamic gambit would succeed.

British policymakers, however, did not stand idly by. They believed as strongly as the Germans did that their Muslim population might prove receptive to Ottoman jihad. Ironically, the British agreed with the Germans that a Caliphate-endorsed jihad could unite the Arab and Islamic world. But while the Germans backed the sitting Caliph, the British sought to replace him with the Hashemite Sharif Hussein, steward of Mecca and Medina, the holy cities of the Hejaz. Much like McMeekin, Schneer in The Balfour Declaration bucks conventional histories of World War I by claiming that Britain’s efforts on the “Eastern Front” ultimately played a significant role in its overall strategy.

The alliance between the British and Hussein seemed natural. The Grand Sharif shared Britain’s concerns about the Ottoman jihad, suspecting that Turkey’s ruling party, the Committee for Union and Progress (CUP), would exploit the war to depose him. Meanwhile, British officials in Cairo, Schneer argues, could “think of no better figure to undermine a Turkish call for jihad than a descendant of the Prophet himself who was also the Grand Sharif of Mecca.” Together, it seemed, Britain and Hussein would wage a counter-jihad against their common foes.

Key to shepherding through the eventual arrangement was Sir Mark Sykes, a British civil serviceman of noble pedigree. Although less intoxicated with the Middle East than his German counterpart Oppenheim, Sykes’ thorough knowledge of the region earned him accolades from his superiors. After returning from a six-month voyage across the Middle East and India at the end of 1915, Sykes enthusiastically endorsed Hussein’s planned rebellion and won its approval in Britain’s War Council. The sides rapidly converged from there. Convinced that the Germans and Turks might actually enlist Arab support with their own package of incentives, the British, in what became known as the Hussein-McMahon correspondence, affirmed Hussein’s independence and recognized his sovereignty over a broad swath of Arabia, the borders of which remained intentionally vague.

Key to shepherding through the eventual arrangement was Sir Mark Sykes, a British civil serviceman of noble pedigree. Although less intoxicated with the Middle East than his German counterpart Oppenheim, Sykes’ thorough knowledge of the region earned him accolades from his superiors. After returning from a six-month voyage across the Middle East and India at the end of 1915, Sykes enthusiastically endorsed Hussein’s planned rebellion and won its approval in Britain’s War Council. The sides rapidly converged from there. Convinced that the Germans and Turks might actually enlist Arab support with their own package of incentives, the British, in what became known as the Hussein-McMahon correspondence, affirmed Hussein’s independence and recognized his sovereignty over a broad swath of Arabia, the borders of which remained intentionally vague.

Secured by Britain’s assurances, Hussein laid the groundwork for his revolt throughout the first half of 1916. Declaring jihad on behalf of his anticipated Arab kingdom, the Sharif began his revolt in early June, as his sons launched armed hostilities on several key Hejazi cities and his followers stormed Mecca. By June 11, Mecca belonged to the Hashemites. The two Arab uprisings nursed along by Europe’s most powerful empires finally clashed on the field, each attempting to out-revolutionize the other. The results, for both Germany and Britain, would prove disillusioning.

The German-British bidding war for the Caliphate—the bedrock of both jihadi insurrections—would also spell those uprisings’ undoing. Thought by both powers to be the one institution capable of rallying the world’s 300 million Muslims behind jihad, the Caliphate instead united otherwise disconnected Muslims as an object of near-universal disinterest. “There was something absurd,” McMeekin writes, “about this shadowboxing between two Christian powers over the Caliphate, an ancient Islamic institution most educated Muslims themselves no longer took very seriously.” In McMeekin’s words, the Caliphate derived its legitimacy from “political-military power” alone. The Caliphate’s clout, then, depended on the clout of its host empire—an empire soon to expire.

The misbegotten war between the Germans and British over the carcass of the Caliphate reflected their fundamental misunderstanding of jihad’s potential sway over Muslims. As McMeekin notes throughout Berlin-Baghdad, the Germans’ attempt to exempt themselves from the Ottoman declaration of jihad (a concept that historically did not distinguish between various groups of infidels) exposed the theological sloppiness of the entire enterprise. In each region visited by Oppenheim’s men—Afghanistan, Persia, Libya, and the Horn of Africa—Germany’s attempt to muster jihad floundered. Outmatched by British naval boats and baksheesh at nearly every turn, the Germans made few inroads in these far-flung outposts of Islam. The forces that they could assemble did not stir the expected mutinies among Muslim troops fighting for Britain.

By sharing the Germans’ faith in the mass appeal of an Islamic religious figure, the British found themselves ensnared in the jihad trap as well, heavily subsidizing Hussein’s underwhelming rebellion. As Schneer relates, Bedouin soldiers besieging Medina in the fall of 1916 abandoned their posts in the wake of a Turkish attack. Hussein’s son Feisal, in command of the operation, rushed to the scene with his own forces, only to witness the left wing of his army suddenly retreat for no apparent reason. Bedouin leaders, writes Schneer, explained to Feisal that “they had retired . . . not from cowardice but only because they wished to brew their coffee undisturbed!” Hussein’s call to jihad failed to stem similar desertions and military gaffes over the course of the rebellion. Unable to amass a sizeable and disciplined army, the Hashemites resorted to guerilla strikes on Turkish forces and the railroad from Damascus to Medina. However much Lawrence of Arabia romanticized this hit-and-run campaign, it proved a mere nuisance to Ottoman armies. British soldiers would proceed to win Hussein’s Arab revolt for him.

Yet of all the blunders caused by the German and British jihad-fetish, the empires’ proclivity to issue empty promises spawned the most discord and future conflict. In that sense, the accounts provided by McMeekin and Schneer document more than just the influence of theology and ideas—they address the lasting impact of unmet expectations.

Germany’s failed jihad can be traced back to its inception: the Berlin-to-Baghdad railroad. Originally scheduled for completion in 1908, the line suffered a slew of delays, yet it muddled through the first years of World War I and received a massive infusion of German funding in 1915. In a grisly twist, however, the railroad—once a beacon for progress—became a path to ruin. In prodding the Ottomans to unleash an ill-directed jihad, McMeekin argues, Berlin invited confusion as to whom the holy war should target and why. Unable to conduct their appointed jihad against the British and French directly, the Turks turned to the closest viable target: the Armenians. Turkish expulsions of Armenian citizens in late 1915 threatened to clog the railway with refugees, choking desperately needed supply lines. The deportations also halted further construction of the Berlin-Baghdad railway by exiling the Armenian skilled workers so necessary to the effort. Germany’s two-pronged revolutionary offensive—one part railroad, the other part jihad—had committed fratricide.

The railway’s death, according to McMeekin, prevented Berlin from delivering much-needed supplies to its jihad agents from the Red Sea coast to Arabia and Afghanistan. Bereft of the resources that the train could have provided, German agents could not fulfill their promises to potential anti-British patrons. In killing the railway, the Turko-German jihad ultimately killed itself.

Britain’s accord with Hussein, on the other hand, allowed it to revolutionize the Middle East far more successfully than its German rival. To establish this partnership, Britain and Hussein had engaged in elaborate negotiations over the course of two years, careful to couch their pledges in artful obscurity. But, as Schneer shows, the festering ambiguities underlying the accord between them that would soon poison Britain’s relationship with the Arab revolt. Negotiations over the extent of Hussein’s kingdom, encapsulated in the infamous Hussein-McMahon correspondence, led the Hashemites to understand that their sovereignty would reach from the Hejaz to the northern Mediterranean port of Alexandretta, down the coast to Jaffa and into Palestine. Yet the British never formally acceded to this demand. In fact, even as they conferred with Hussein, they pledged parts of that same territory to the French in the Sykes-Picot Agreement, which remained secret until 1917. The British endorsed yet another aspirant to some of the territory in question by approving the Balfour Declaration, which declared that the British government would use its “best endeavors” to facilitate “the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” By 1917, the British had triple-promised much of the land to which Hussein laid claim.

However skillfully it conducted its diplomacy, Britain did not have the means to meet its overlapping obligations. As arrangements secret and public became known, Schneer writes, British duplicity triggered profound and unrelenting distrust “of all parties by all parties.” Hussein’s family—feeling robbed of its inheritance—found itself expelled from both Syria and the Hejaz within six years of the war’s end. And the Zionists eventually saw their promised territory whittled away by successive British White Papers. Britain’s Arab revolt may have broken the seat of the Sultan-Caliph and its supposed potential to spearhead pan-Islamic jihad, but it laid the ground for countless future problems.

Germany and Britain’s respective missteps were rooted more than anything else in their projection of their own self-regard onto Arabia. Germany’s plan to build a railroad from Berlin to Baghdad represented, according to McMeekin, “just the kind of half-mad imperial enterprise fin de siècle Europeans excelled in.” Britain’s attempt to outfox its interlocutors emanated from a faith that it could remain one step ahead of any diplomatic trouble, no matter how many promises it distributed. Seen in this light, the Germans and British may have viewed jihad as an extension of their own arrogance: If we can unite to construct technological wonders and reshape the globe, why is the Islamic world incapable of summoning jihad? As Germany and Britain imagined their own limitless capacities, they demanded the same mythic potential—and desire to carry out that potential—from others as well.

McMeekin argues that Britain and Germany’s follies in the Arab world spawned a Frankenstein-like jihad that, once awoken, turned on its progenitors. While a strategic failure during World War I, McMeekin writes in his epilogue, “the Kaiser’s promotion of pan-Islam . . . threw up the flames of revolutionary jihadism as far afield as Libya, Sudan, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, Iran, and Afghanistan, which never entirely died down after the war.” By promoting an “atavistic version of pan-Islam,” Oppenheim and the Kaiser committed a “breathtaking error in judgment, and we are all living with the consequences today.” In the same way, Schneer believes that Britain’s actions “sowed dragon’s teeth” that would later come to haunt it.

Yet in locating the origin of today’s jihadi threat in early-20th-century Western gamesmanship, McMeekin overstates his case. Modern-day Islamic extremism emerged from an entirely different and complex set of circumstances—most notably, as a violent reaction to the tyranny of secular Arab dictators themselves. And in passing over these vital fluctuations, McMeekin subverts the true lesson of his work: that Muslims, from jihadis to liberals, have their own desires that they, regardless of Western meddling, will continue to pursue.

That is a lesson worth remembering today. If the Western powers were tempted a century ago to harness jihad for their own purposes, they now face the opposite temptation: to see in the rebellious young men and women in Western clothing, the bloggers and Google executives of Tahrir Square, as their potential allies in the war against contemporary jihadis. But as the United States considers and reconsiders its approach to the people of Tahrir—in Egypt and across the Arab and Islamic world—it would do well to remember that the protesters are neither strategic proxies nor avatars of the American dream.

Suggested Reading

Big Tent

The American religious landscape that Uzi Rebhun sketches out in his new book, Jews and the American Religious Landscape, is marked by virtually boundless freedom and pluralism, as well as increasing fragmentation, due to the growth of “self-searching and religiosity by choice.”

Those Days Are Gone Forever

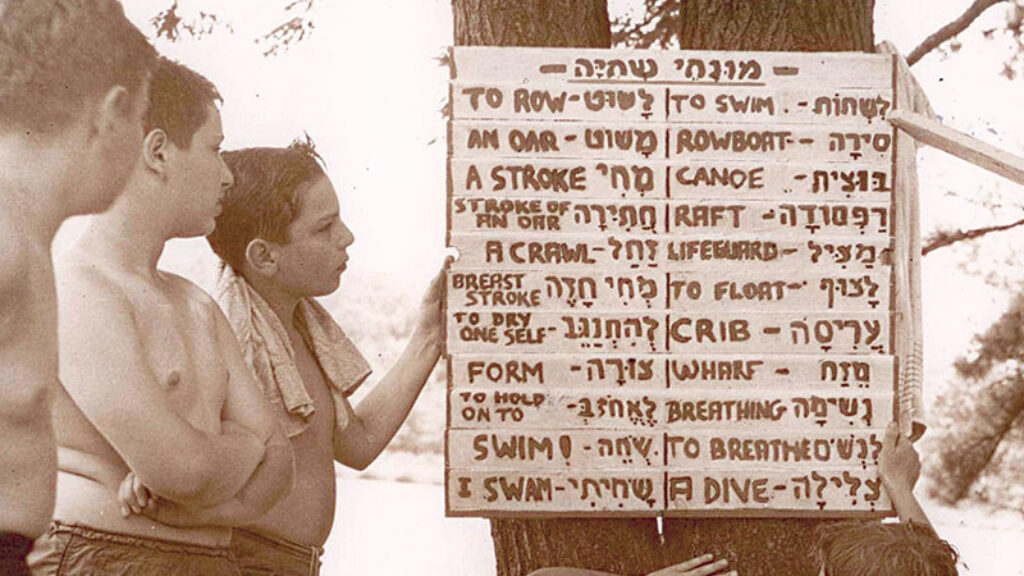

What, exactly, is camp spirit?

Manufacturing Falsehoods

An immense echo-chamber has been built, and the line is always the same: Israel is not allowed to be a country like any other.

Two Poems

Two untitled poems by Avraham Halfi, translated by Leon Wieseltier.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In