Valhalla in Flames

In his fascinating 1996 book, Beethoven in German Politics, 1870–1989, the historian David B. Dennis described the way that Beethoven came to serve every ideology in German political culture. The brief-lived revolutionary republic in Bavaria was inaugurated with orchestral performances of the Leonore and Egmont overtures. A few years later, Beethoven’s symphonies would serve as the introductory music when the German radio announced the birthday of Adolf Hitler. It is a depressing history with a depressing lesson: Culture can be made to serve any end, even the most barbaric.

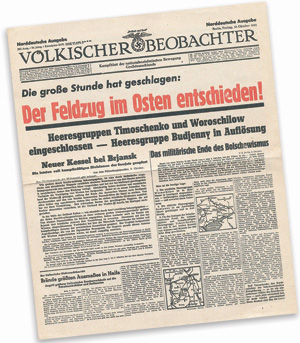

In his new book, Inhumanities: Nazi Interpretations of Western Culture, Dennis has now broadened his field of vision to address the way that the Nazis constructed a general canon of the German past. His historical task would be impossibly large were it not for his decision to confine himself to an historical summary of a single newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter (which translates, somewhat awkwardly, as “The Folkish Observer”). The paper began as an unremarkable biweekly until, bought by the Nazis in 1920, it eventually became a daily and swelled in circulation, reaching 30,000 copies in 1929 and over one million copies upon the eve of World War II. It was, Dennis reminds us, “the most widely circulated newspaper in Nazi Germany.”

Although the Völkischer Beobachter was aimed at the masses, it devoted a considerable share of its attention to matters of culture and specifically to Germany’s cultural heritage. In his book Dennis documents the various themes and conceits by which the Nazis sought to dignify their political ideology by constructing a cultural prehistory in its pages. In the words of the great German-Jewish émigré historian George Mosse (whose work clearly served as a model for Dennis), “building myths and heroes was an integral part of the Nazi cultural drive.” They knew they would encounter resistance, and they accordingly committed themselves to the project of redefining Nazism as the organic culmination of Germany’s cultural past. Most of all (as one writer put it), “to win over to our movement spiritual leaders who think they see something distasteful in anti-Semitism, it is extremely important to present more and more evidence that great, recognized spirits shared our hatred of Jewry.”

Few writers, poets, and musicians of the past were safe from this project. In the pages of the Völkischer Beobachter readers could find commentaries on nearly all the great figures of both the German and the European canons, including Michelangelo, Machiavelli, Shakespeare, Goethe, and Schiller, along with the great composers, including Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert, and Wagner. In fact, it is a bit distressing to see just how closely the Nazi canon resembles the syllabi of Western Civilization courses at, say, Reed College or Columbia University. (You can find most of these names cut in stone on the exterior frieze of Columbia’s Butler Library.)

Canons, then as now, have always helped to establish present legitimacy on the basis of past accomplishments. The Nazis, after all, began as upstarts, revolutionaries who sought to challenge the traditional political system of the Weimar Republic, and they had to manufacture not only their party symbols and uniforms but also their bond to the German past. Anti-traditionalists who craved tradition, they created the illusion of cultural continuity through constant appeals to the literary, philosophical, and musical greats. As Dennis observes, the Völkischer Beobachter “repeated the main themes of Nazi culture with liturgical regularity.”

If repetition is an effective strategy for ideological indoctrination, it is also an effective way for the historian to convey the mind-numbing suasion of Nazi propaganda. The aptly titled Inhumanities is not a small book. In its concluding pages, Dennis offers an unusual admission: “[I]t is possible,” he writes, “that in the process of reviewing every page of a daily newspaper over a twenty-five year run, mostly on microfilm, I may have missed some relevant content.” Possible, but unlikely. His book is so comprehensive, and its summaries so exhaustive, that one would be surprised to learn of any serious omission. A great deal of the book consists of quotations from the Völkischer Beobachter, and Dennis organizes these quotations into different chapters, each devoted to a major theme (attitudes toward romanticism, criticism of the Enlightenment, music after Wagner, patriotic Germans, and so forth). The overall effect is that of a catalog of Nazi cultural ideology.

Unfortunately, this is not the most fruitful method for historical analysis. Dennis’ exercise in content summary has the effect of portraying Nazi ideology as a more or less static phenomenon that remained unchanged, despite the transformation of the party from its early years of minority rebellion to its final decade of totalitarian control, when nearly all signs of cultural diversity had been eliminated. Did the Völkischer Beobachter modify its portrait of Germany’s cultural heritage over the course of 25 years? Dennis quotes indiscriminately, sometimes on a single page, from essays separated by more than a decade. It may be that Nazi ideology aspired to a kind of eternity, but it is a defining characteristic of fascism that it functioned more as a party movement than a stabilized regime. Whether this restless dynamism also meant changes in cultural politics is a question that deserves further exploration.

Cultural history calls for interpretation as well as collection. But Dennis’ book, though long on evidence, is rather unforthcoming on matters of significance that other scholars have addressed with greater theoretical acumen and with the conceptual resources borrowed from many disciplines. Dennis occasionally cites Eric Michaud’s The Cult of Art in Nazi Germany, which builds upon earlier claims by Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe and Jean-Luc Nancy regarding “the Nazi myth,” but he does not adequately address the questions these scholars and others have attempted to answer. What was the deeper meaning of the Nazi appeal to a cultural heritage? Was Nazism an “aestheticization of politics,” as Walter Benjamin suggested, or is Dennis right to object that Nazism achieved a “politicization of aesthetics”? Does the latter rule out the former or should one (more plausibly, perhaps) see them as complementary strategies of fascist culture? And what distinguishes such strategies from those known to us from the history of the Eastern-bloc communist tyrannies or from the numerous attempts at cultural-religious consolidation in contemporary authoritarian movements across the globe? The reader closes Inhumanities exhausted by the harangues of Nazi ideologues, though grateful to the author for translating and organizing the material into an accessible form. But a nagging sense of dissatisfaction will linger, a feeling that very few of these questions have been explored.

The self-reflexive question historians ought to ask themselves is how we should understand the relationship between the Nazis’ genealogies of culture and our own efforts to uncover the cultural roots of National Socialism. It should unsettle us, I think, that the Nazis’ own narratives bear such a striking resemblance to the cultural-historical studies of Nazism that rose to prominence after the war. Take, for example, the 1964 work by George Mosse, The Crisis of German Ideology: The Intellectual Origins of the Third Reich. Synthetic, broad-ranging, erudite, Mosse’s was the book to read if one wished to comprehend how the delicate canons of German high culture could lend their prestige to the brutality of a modern political regime. What Mosse and distinguished colleagues such as Leonard Krieger and Georg Iggers took for granted was the conviction that National Socialism, despite all of its modern trappings and mass-media apparatus (the techniques it shared with slick advertising campaigns, its self-promotional slogans, its use of the radio) was best understood as the spawn of a distinctively German cultural inheritance. Germany, after all, was the land of Dichter und Denker, poets and thinkers, not to mention musicians. It should not surprise us that the learned refugee children of the German or German-Jewish cultured class (Bildungsbürgertum) who had fled the Nazi plague would go hunting in their own libraries for the sources of the disease. And why not? This was the evidence nearest to hand. For a scholar of erudition such as Mosse, it was tempting to see in Nazism a pathology born from the same world of letters in which he had been schooled and which had betrayed him so shamefully.

However, notwithstanding the power of this interpretative method, a new generation of historians eventually turned against Mosse and the method he helped to pioneer. By the 1970s and 1980s, a neo-Marxist trend in German historiography challenged the older paradigm according to which there was something distinctively and even exclusively “German” about Nazism, and instead they sought to revive the older conception of Nazism as a variant of fascism continuous with the politics and social-structural pathologies of modern capitalism. This was especially true of the 1984 work, The Peculiarities of German History: Bourgeois Society and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Germany, co-authored by two brilliant British historians, David Blackbourn and Geoff Eley. It would be hard to exaggerate the achievement of this revisionist school. Above all, it challenged the view of Nazism as a uniquely German phenomenon that had come into view when the German middle class, their revolutionary hopes defeated in 1848, had strayed from the safe path of development in the liberal-democratic West. For the revisionists, it was not hard to see that this idea of a German Sonderweg, or special path, had served an ideological purpose: In blaming Germany alone for fascism’s rise, it granted a badge of innocence to capitalism and the cold-war West.

For Blackbourn and Eley however, there was no such Sonderweg (a term, ironically, that in earlier times German nationalists had embraced). In fact, in the 19th century the various territories from which Bismarck would forge the unified German Empire began to hum and thrive. Indeed, this was a bourgeois society no less vibrant and promising than that of France or England, from whom Germany’s path had supposedly diverged.

But the revisionist argument cut two ways: If Germany was no less bourgeois than other European lands, then those other lands were no less susceptible to fascism. It therefore seemed far more plausible to seek the origins of fascism in those features shared by all modern commercial societies, with the implication (often unstated) that fascism was the final stage in the crisis of capitalist modernity. Echoing a theme that had already been developed by Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer (especially in their monumental Dialectic of Enlightenment) the revisionist historiography was both depathologizing and pathologizing: Germany no longer stood alone under the dark shadow of its fascist past; instead, that shadow loomed as an ever-present possibility across all of modernity.

From the historian’s perspective, what makes Inhumanities such a perplexing contribution to the literature on the Third Reich is that it serves as a powerful reminder that the Nazis themselves believed in a cultural Sonderweg. Laboriously, proudly, in essay after essay, their historians, literary scholars, and musicologists helped to construct a vision of the past that explained how Nazism had emerged organically out of Germany’s unique cultural inheritance. (Dennis does not clearly indicate where he stands on the Sonderweg, but at one point he asserts that the mindset of “eliminationist” anti-Semitism was already in place as early as 1923, a claim that would support a thesis of longer-term ideological continuity.)

There are, to be sure, obvious differences between the postwar cultural histories of the Sonderweg and the crude, tendentious articles that appeared in the pages of the Völkischer Beobachter. The postwar cultural historians were doing their very best to determine the actual origins of National Socialist ideology, and we cannot fault them if their efforts sometimes read a bit too much into the diverse intellectual and cultural currents of the previous century. (Was “Turnvater Jahn,” the nationalist gymnastics guru of the early 19th century, really a source for the German ideology of the 20th century? Was Herder really a proto-totalitarian?) The contributors to the Völkischer Beobachter were, in contrast, crude ideologues, constructing a useable past even when usability demanded the most absurd historical and cultural distortions. Still, there is an uncomfortable similarity here that Dennis does not consider. Much like the writers for the Völkischer Beobachter, the postwar cultural historians assumed that the ultimate significance of culture is political.

The risk in this brand of cultural history is that it confirms a conventional prejudice that remains deeply rooted among historians: History is always and must remain the history of politics, and in the final analysis “culture” is always a cipher for power. The message is clear: Genuine history is political history, the history of states and international relations, economics, and ideologies, and if one studies culture it is only legitimate because culture can be exposed in the final analysis as politics by other means. What makes the cultural histories of the Sonderweg so distressing when one reads them today is that they had the unfortunate effect of reproducing, despite their own humane purposes, the culture-as-politics conceit that has held sway amongst cultural nationalists of every variety—not only during the Third Reich and not only in Germany.

It is hardly surprising to read that of all the heroes in the National Socialist pantheon, Richard Wagner stood supreme. Famous for his anti-Semitism and especially for the notorious screed Judaism in Music, Wagner remained (in the words of Joseph Goebbels) the “most German of all Germans.” But here, too, the Völkischer Beobachter faced serious difficulties. A well-known story has it that Wagner was the illegitimate son of an actor, Ludwig Geyer, a man Richard’s mother married after her first husband had died. Geyer was rumored to be a Jew, and it seems that Richard himself may have believed the story of his Jewish ancestry. A writer for the Völkischer Beobachter set out to vanquish this calumny once and for all by arguing in the alternative: First of all, Ludwig Geyer and Wagner’s mother had refrained from sexual relations until their marriage, so Richard could not have been Geyer’s son; moreover, Geyer wasn’t Jewish. It’s like the old joke about the borrowed kettle, which had the hole in it from the beginning, and wasn’t borrowed anyway.

The case of Wagner is illustrative of a general premise that underlay all of the writings in the Völkischer Beobachter: the belief that culture is essentially the property of a people. Those of us who enjoy listening to Wagner’s music recognize the falsity of this conceit, even if Wagner himself, in his moments of nationalist chauvinism, betrayed the higher truth that can be heard in his musical work. Against every nationalist who boasts a bit too loudly that culture is a “heritage” and something that belongs to his own people alone, it merits repeating that aesthetic creation defies the logic of belonging.

Culture may be used as a vessel for power, but it also itself possesses another kind of power, and this powerless power—call it beauty—poses an eternal challenge to all powers that claim political supremacy. This is why the passages Dennis quotes from the Völkischer Beobachter can still provoke such head-shaking disbelief in the reader. That Beethoven harbored sympathies for the French Revolution was, for instance, a source of embarrassment that the newspaper tried to minimize. Though Beethoven “suffered from revolutionary fervor,” one essay explains, “his heart remained with his German Heimat.”

It is true, as the musicologist Scott Burnham has shown, that one hears strains of the “heroic” especially in the middle period in Beethoven’s career, but it is a humanistic heroism that has nothing to do with the inhumanities of the Third Reich. And, in the fragmented, broken style of his late period (as beautifully analyzed by Adorno) the composer offered the strongest retort to the barbarians of the future who would try to enlist him as a hero in their nationalist pantheon. This is a humanity stronger than the heroism ascribed to him by his “folkish observers” and stronger, even, than ideology itself.

So, too, Schubert: His music (in the words of a Bavarian cultural minister) stood as a “monument to the German soul and mind,” whereas the musicologist Susan McClary has detected in his music “feminine endings,” or cadences of deceptive beauty, which, in their pure aestheticism, defeat all gestures of monumental aggression. The same, finally, might even be said of Wagner’s Ring des Niebelungen: When Brünnhilde rides into the flames and the ring is at last restored to the maidens of the Rhine, the orchestra, concluding on a D-flat chord (a whole step below the key of E-flat with which the tetralogy began), permits the violins to come to rest on a delicate and sustained note of high A-flat, and Siegfried’s heroism, a heroism that was never free of brutality, is forgotten.

Suggested Reading

Hidden Master

The closer we look at Green's theology, the more radical it turns out to be.

The Symbol Catcher

My friends and I took for granted that the connection between the cards and the players they represented wasn’t just arbitrary.

Palestine Portrayed

The 1948 War and the problems it left unresolved have returned to the top of the agenda for both diplomats and historians.

Tradition and Imagination

Jewish fiction’s long memory.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In