Tradition and Imagination

“You were like really always into being Jewish weren’t you?’” an old classmate asks the narrator of “Tales of My Great-Grandfathers,” one of the two new autobiographical additions to Johanna Kaplan’s recently reissued story collection. “‘I guess so.’ I said this with reluctance, immediately feeling defensive. Because in a time of so much ferment and ecstatic disruption, who could believe it? Hear about Johanna? Pathetic, really—still into her same old boring Jewish trip.”

Like most of the stories in Loss of Memory Is Only Temporary, “Tales of My Great-Grandfathers” is set in New York in the decades after World War II. But the sentiment with which it opens isn’t bound by time or place. It’s one that’s familiar to just about anyone who has spent both her youth and professional life immersed in the Jewish world—studying, writing about, or soliciting money on behalf of, Jews. The enduring question is: am I ever going to outgrow this?

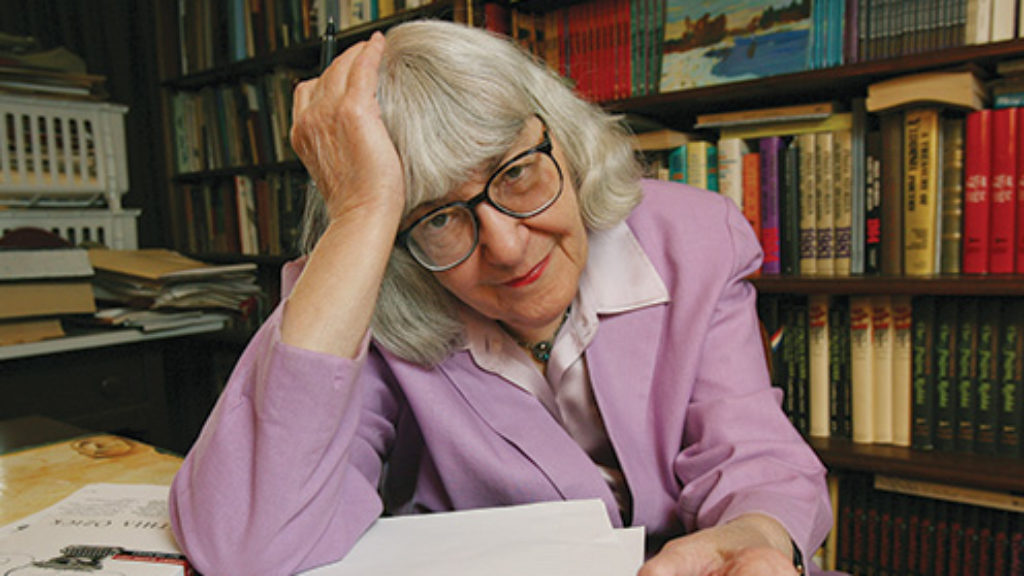

Kaplan’s work, scrupulously attentive portraits of postwar American Jewry, offers her answer. Originally published as Other People’s Lives, this collection was a 1976 finalist for the National Book Award for Fiction. It was soon followed by a novel, O My America!, which tells the story of an enigmatic, chaotic Jewish radical as seen through the eyes of his daughter. A new Jewish novel, tentatively titled Forbidden, is in progress after more than forty years of silence.

As for Kaplan’s reissued story collection, the focus of the expanded edition is unchanged: the artful stories explore the day-to-day circumstances of characters so richly drawn that they need little in the way of manufactured drama. Thus the workaday settings of most of the stories: a gone-to-seed Upper West Side apartment, a girl’s sickbed, a Zionist summer camp, the coffee shop at a psychiatric clinic.

Accompanying every story is another presence—the past—which exerts a pull so strong on Kaplan’s characters that it could almost be said to be an agent of its own. How to come to a grudging truce with history is the central question of her stories. (A more contemporary way to put this might replace “history” with “trauma,” but it would miss a point that Kaplan’s characters feel deeply: it’s not only past pain that’s hard to live with.) And though this struggle is heightened at a certain age—most of the poignant contests are dramatized through young female protagonists—Kaplan’s work suggests that this is an abiding conflict in a Jewish American life.

Kaplan, whose distinguished fans include Cynthia Ozick, Francine Prose (who introduces the volume), and Ruth Wisse, is sometimes called a “writer’s writer.” But this label, often code for “technically accomplished and overly subtle,” doesn’t do justice to the pleasure of reading her work. With Kaplan, there’s none of that anxiety that sometimes marks the experience of reading contemporary fiction—waiting for the unbelievable phrase or character to break the spell. Her facility with language, her pitch-perfect dialogue, her restraintin matters both of explanation and moralizing, frees the reader to, well, enjoy. Take this wonderful image from “Babysitting”: “I looked at Pietro, the older one, and then at Sascha, a round-faced little girl with wild blonde curls; when she leaned back in her crib, flushed and overtired, she looked like a confused, unkempt grandmother.” Or Kaplan’s description of a folk-dance instructor in “Sour or Suntanned, It Makes No Difference”:

With her tiny, tight dark features and black, curly hair, she flew around the room like a strange but very beautiful insect, the kind of insect a crazy scientist would let loose in a room and sit up watching till he no longer knew whether it was beautiful or ugly, human or a bug.

Kaplan also has a dry wit. In a story set in a Zionist summer camp, the reluctant Miriam is cast in a play about the Warsaw Ghetto partisans, in which she must warn the ghetto residents of Nazi plans. “‘So the whole thing is that you copy Paul Revere,’” her bunkmate says. Miriam answers, “‘The only kind of Paul Revere it could be is a Jewish kind. Everyone dies and there are no horses.’”

Kaplan’s young women listen more than they speak, and they think perhaps more than is helpful. But if these girls and young women are characterized by anything, it’s by what they lack: a firm boundary between their outer and inner worlds. Like all adolescents, Kaplan’s characters are struggling to individuate, but they’re trying to do so while carrying a cultural and historical inheritance that threatens to overwhelm them.

For Miriam, who is laid up at home in “Sickness,” that psychic porousness is dramatized through feverish narrative interludes, in which Jewish history invades her reality. One moment, she’s eavesdropping on her mother and neighbor as they defame Jewish doctors—“‘Let’s face it, Manya,’ she tells my mother. ‘You’ll never get satisfaction. A Jewish doctor is a Jewish prince,’”—the next, she’s transported into a dream or reverie about Joseph Nasi, a figure in the Ottoman court of sultans Suleiman the Magnificent and Selim II. (In Miriam’s dream, he is also a skilled physician—though in real life, that role belonged to Joseph’s father.)

And Miriam is not the only one prone to fantasies; sensitive Louise Weil, the protagonist of the novella-length “Other People’s Lives,” is similarly held captive. The daughter of divorced Viennese refugees, college-age Louise is prematurely released from a mental hospital and finds herself a boarder in the home of Maria Tobey. Maria is a German immigrant in whose Upper West Side home pots are always banging, someone is always talking, and the neighbors stream in and out of the house “as if it were an extension of their own.”

Louise, like all of Kaplan’s young heroines, is a good listener. Often, she is the only one: in Kaplan’s marvelous dialogue, other people’s observations are merely a hook on which a character can hang her own monologue. But for Louise, that listening state seems almost pathological, a form of escapism rivaled only by her intrusive fantasies about her neglectful, far-off family: her mother, who moved to London when she was first hospitalized; her father, who has made a new family in the Dominican Republic; a sister who moved to Sweden, jettisoned her past, and ignores Louise’s letters.

Like most of Kaplan’s young protagonists—but more so—Louise is held captive by the past, existing in a no-man’s-land between sickness and health, between real life and reverie. “‘I hate history,’” she tells her psychiatrist at one point and is “surprised at her own vehemence, and knew that what she meant was that she hated her own.”

Louise’s story concludes hopefully, with the suggestion that she might at last be able to find her way into some kind of real life, one in which her personal history does not seal up the future. Perhaps unexpectedly, it’s the Gentile, former Hitler Youth Maria who offers the model: “‘You think every time: This is my life. But it’s not. You don’t know. You know only always that it can change, be different.’” But it’s not clear that what worked for Maria will work fully for Louise or for Kaplan’s other young protagonists, because if there’s one thing that these stories suggest, it is that to be Jewish—and particularly to be Jewish in New York in the 60s and 70s—is to accept that the future, while not sealed up by the past, is formed by it. In the words of the narrator in “Tales of My Great-Grandfathers”: “the past, and with it the force of external events not only shapes the arc of lives, but also infiltrates even the most private spaces of the imagination.”

It’s this view of the past that lies at the heart of “Loss of Memory Is Only Temporary,” the collection’s most perfect story. It features Naomi, a medical resident at a psychiatric clinic, who is visited by her fretful aunt, the woman who raised Naomi after her parents were killed in an accident. The aunt, convinced that Naomi has cut ties with her past entirely (“‘to you it doesn’t matter what you forget’”), makes every attempt to drag her back into it: “‘Naomi, how do you know where you’re going? You—who could get lost on your way to the corner to get a loaf of bread. It drove your mother crazy. Remember?’” and “‘Anyway, since when do you eat lunch?’” and “‘Since when are you interested in hats?’”

In one exchange, the aunt (who thinks of Naomi as “the stone”) frets over the fate of a patient to whom Naomi is to administer electroconvulsive therapy:

“But she’ll forget things. I know what happened to Schreibman’s sister-in-law. She woke up in the morning and didn’t know what day it was, she went to the bakery and couldn’t remember a single salesgirl.”

“Loss of memory is only temporary,” the stone said.

“There are conditions in which ECT is indicated. Involutional depression, for instance.” . . .

“How do you know if that’s what she had? You don’t even know who I’m talking about.”

“Severe depression associated with menopause You know what that is—change of life.”

It’s difficult not to feel sympathy for the aunt who desperately wants to connect with Naomi over their shared loss of a sister and a mother. But her insistence that not forgetting means not changing is harder to swallow. For despite what her aunt believes, Naomi has real ties to her past: a childhood friend she keeps in touch with, vivid memories, knowledge of her ancestors. Whatever forgetting she’s done has not been out of disinterest in the past but out of necessity for survival.

And yet, the joke is on Naomi too. One of the most remarkable features of Kaplan’s collection is the uncanny way that the past comes looping back around, the same characters and images recurring in different times and stories: kidnapped children, Polish-born mothers, oranges, psychiatry. Near the end of the story, we learn that Naomi’s chosen professional path—so different from that of her cousin’s suburban motherhood—is perhaps not the radical expression of autonomy that it seems to be. Naomi’s Great-aunt Masha was a doctor too. The past, Kaplan shows us, infiltrates even the most private spaces of the imagination.

Suggested Reading

Miami Vices

As it is, The Orchard reads more like Days of Our Lives than Daniel Deronda.

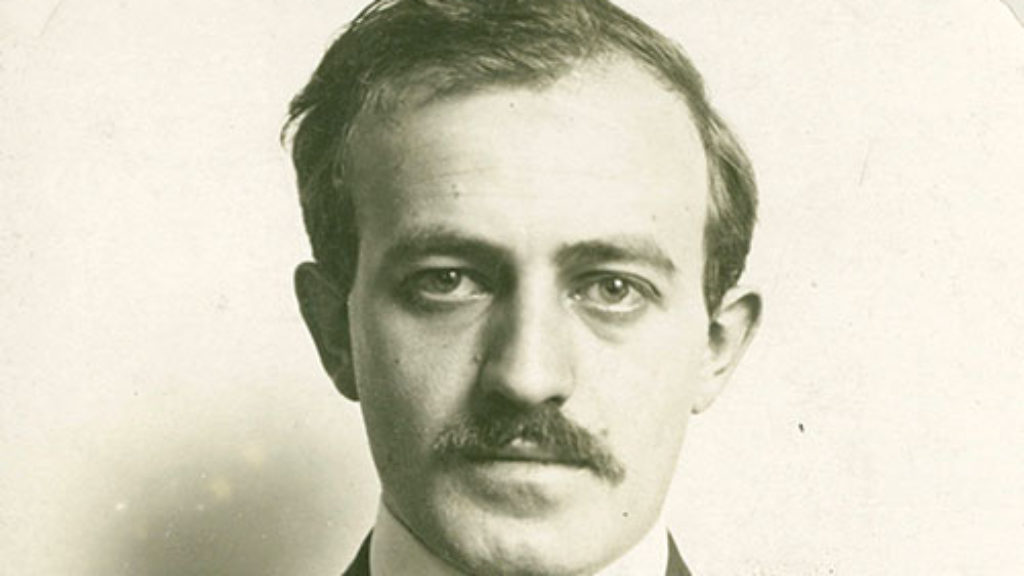

Some Kind of Genius

Ben Hecht’s life should come with a warning label: Biographer, beware. A trickster, a prankster, a cool Wildean ironist, he was always a fast-moving target.

Fiction and Forgiveness

Dara Horn’s novel goes down to Egypt to guide its perplexed characters through a Joseph story.

Cynthia Ozick: Or, Immortality

Ozick is as marvelously demanding, harrumphing, and uncompromising as she has always been.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In