Hidden Master

In recent years, the movement variously known as Jewish Spirituality, Jewish Renewal, and Neo-Hasidism has surged forth from independent prayer groups and study-based communities into the mainstream liberal synagogues. Along the way, it has helped pry the Holocaust and Israel from their central place in American Jewish identity. A decade ago the philosopher Michael Morgan made an important observation about the movement’s serious commitment to religious experience and traditional ritual practices, and apparent disinterest in theological questions. “These trends point to God, the divine and especially to questions about our access to transcendence or our experience of God,” which “should point to the notion of divine revelation and compel us to a careful reconsideration of it, [but] I do not see much activity of this sort.”

For a while, at least, it apparently sufficed if God was merely hummable. Now Arthur Green, a distinguished scholar of kabbalistic and Hasidic thought, former dean of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, and current rector of the Rabbinical School at Hebrew College, has provided a systematic theology for the movement of which he has as much claim as anybody to be the intellectual leader. In Radical Judaism: Rethinking God and Tradition, Green presents us with a Judaism built on the familiar three pillars of God, Torah, and Israel. But the closer we look, the less familiar they turn out to be.

In his introductory autobiographical remarks, Green briefly relates how his childhood faith in a personal God succumbed to “theodicy and critical history.” By the time he was in college, he realized that he could no longer believe in an all-powerful God who permitted the occurrence of tragedies such as his mother’s early death and the Holocaust. At the same time, the critical study of Jewish sacred texts convinced him that they were man-made. The experience was not entirely disheartening. His reading of Nietzsche inspired him to feel some “joy at the death of my childhood God and liberation from all that authority.”

The loss of this particular God marked not the end but only the beginning of Green’s quest for something that he could still call “God.” He has persisted because he refuses to deny “the possibility and irreducible reality of religious experience.” Green treasures moments when the “mask of ordinariness falls away, our consciousness is left with a moment of nakedness, a confrontation with a reality that we do not know how to put into language.” In Radical Judaism, he aims to provide a theology that makes sense of such experiences without trying to express them.

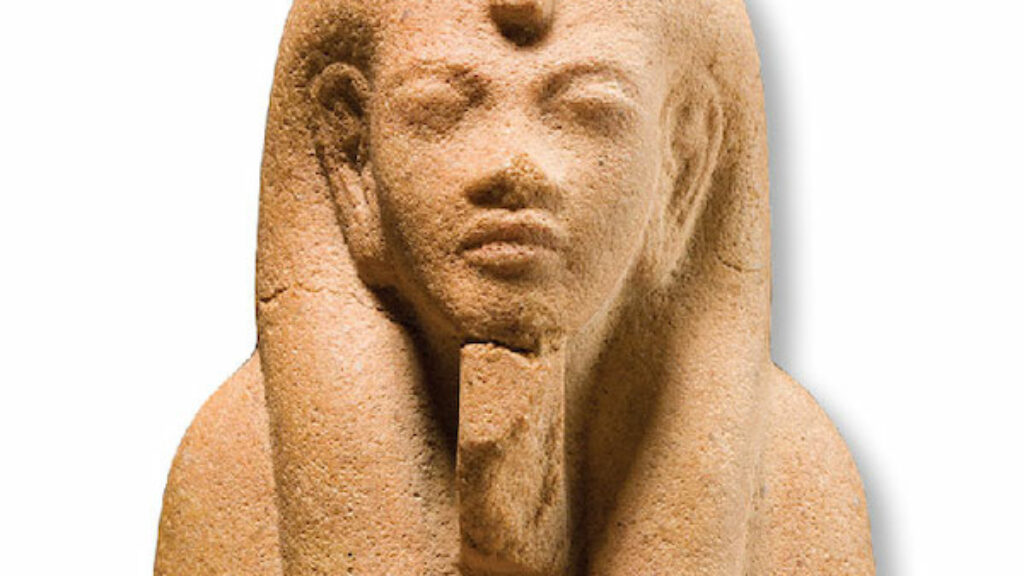

Even a Neo-Hasid needs a “rebbe” for such a quest, and Arthur Green has three: Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter (the Gerrer Rebbe) of the late-nineteenth century; Hillel Zeitlin, a theological journalist and activist who was martyred in the Warsaw Ghetto; and Green’s own teacher, the renowned theologian Abraham Joshua Heschel. Green gratefully recognizes all three and one hears echoes of each in his prose. His serious puns and literary inversions recall Alter’s classic work of Hasidic thought Sefat Emet; his impassioned argument recalls Zeitlin; and, occasionally, he reaches for the soaring poetry of Heschel. However, as we shall see, his theology is really more indebted to a fourth anti-mystical, and almost hidden, master.

To determine what it is that one is undergoing in moments of true religious experience, Green looks not only inward but outward as well. God, for him, is a personification of “the inner force of existence itself, that of which one might say: ‘Being is.‘” He refers to it “as the ‘One’ because it is the single unifying substratum of all that is.” God is the “life force that dwells within the universe and all its forms, rather than a Creator from beyond who forms a world that is ‘other’ and separate from its own Self.” This One “lies within and behind all the diverse forms of being that have existed . . . clothed in each individual being and encompassing them all.” Green’s theological position is, as he aptly describes it, one of “mystical panentheism.”

One cannot, of course, ask of such a God what It wants of us, but one can talk about what knowledge of It ought to elicit from us. This is something that Green explains in the context of a discussion of evolution that has an oddly teleological, almost Hegelian, ring to it. Evolution, for him, is not a process indifferent to our well-being but one that we can perceive to be “meaningful.” God does not direct nature or Being, consciously planning how complex life forms, especially humanity, will evolve. The One, or Being, or “unifying substratum”—Green uses all three, along with “God,” almost interchangeably—is rather “the underlying dynamis of existence striving to be manifest ever more fully in minds that it brings forth and inhabits, through the emergence of increasingly complex and reflective selves.”

We human beings are therefore called upon by “the One manifest within us” to respond to the question God posed to Adam in Eden: “Ayekah?“—”Where are you?” What this question means is: “Are you extending My work of self-manifestation, participating as you should in the ongoing evolutionary process, the eternal reaching toward knowing and fulfilling the One that is all of life’s goal?”

Fully aware of how remote from Judaism his mystical panentheism may seem to his readers, Green devotes an entire chapter of his book to a “Jewish history of ‘God'” designed to demonstrate its indigenous roots. The chapter moves from the Bible through medieval philosophy, Kabbalah, and Hasidism, highlighting theological moves in the direction of panentheism, and culminates in an announcement that “the time has arrived for Jewish panentheism to come out of the closet, as it were.”

That may be so, but Green’s chosen masters would hardly have agreed. His “most revered teacher” Abraham Joshua Heschel was a champion of theological “dualism.” Heschel understood God to be in search of man, relating to him from almost the fullness of His being. “Almost,” because Heschel reserved God’s inner space, His most true being, to Himself. He taught that real relations between God and man can only exist on the basis of dual identities. Indeed, Heschel had the prophets respond to God’s pathos with sympathy for the Divine’s plight in being affected by this concern for man. Green tells us that when he became enamored of Christian radical death of God theology, Heschel suggested that he begin with the Hasidic masters, including the Sefat Emet. But this seems to have been Heschel’s attempt to save a brilliant student from what he termed “blasphemy,” not a suggestion that this was the real endpoint of Hasidic thought.

Hillel Zeitlin did indeed express a Hasidic panentheism in which the world dwells within God. “The light of the unlimited (of whom we know not a thing),” he wrote, “fills and surrounds everything.” But he also wrote that “aside from the world of appearance . . . there are many other worlds more sublime . . . secret and hidden.” For Green, on the other hand, there is only one universe and it, or its substratum, is God.

Green’s hidden master is a bit like his God in that he is hiding in plain sight. Mordecai M. Kaplan, who taught at the Jewish Theological Seminary where Green was ordained, founded the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, which Green later led. In a footnote, Green tells us that he omits any discussion of Kaplan’s work because he was “alienated from the mystical tradition and did not see the earlier roots it might have provided for a different approach to the question of God.” And yet listen to Kaplan in Judaism as a Civilization:

There is only one universe within which both man and God exist. The so-called laws of nature represent the manner of God’s immanent functioning . . . God is not an identifiable being who stands outside the universe. God is the life of the universe, immanent insofar as each part acts upon every other and transcendent insofar as the whole acts upon each part. [emphasis in the original]

The echoes of this are real in Green’s Radical Judaism rather than rhetorical, as they largely are in the cases of Alter, Zeitlin, and Heschel. For Kaplan, as for Green, what is real is the immanent life of the universe. Kaplan’s “transnaturalism” is reconstructed in Green’s panentheism. Kaplan’s God transforms chaos into order, while Green’s allows for the evolution of higher complexity. For both, God is only transcendent in that we don’t see Its presence as well as we should. For both, reality is the Immanent, which means the unity of all reality, with man at its self-conscious peak. For both Kaplan and Green, God is a “what” rather than a “who.” For both, the universe is constructed so that human beings can find “salvation” (Kaplan’s term for man’s self-fulfillment). Both present optimistic theologies that have no sense of the tragic, and tend to ignore evil.

The close similarity between Kaplan’s transnaturalism and Green’s panentheism ought to be a cause for concern on Green’s part. For Kaplan’s doctrine, which was first received with so much excitement, has disappeared. The main reason for this is that it’s boring. There is no actual God with whom one can have a relationship. The God of the Bible and the Rabbis asks, entreats, and demands, and is saddened when His people fall short. And there are times when God doesn’t seem to be fulfilling His part of the covenant. But when things go right and also when we imagine how it will be when things go right—Shabbat and holidays—joy and tranquility are manifest.

The spiritual life of classical Hasidism is arguably even more dramatic. Every action—moral, ritual, trivial—and preparation can provide a moment in which union with God, devekut, is achieved. And not to strive for it is no less than tragic, for then you and the universe are lost and harm is caused on high. And for both those who believe in the demanding God and for those who seek devekut, evil is real enough and has to be fought.

If Green’s God bears little or no real relationship to the God of Israel, the same is true of his Torah. Viewing the Torah, as he does, not as the literal word of God but as a purely human response to “the wordless divine call,” he interprets its text very freely. Consider, for instance, his interpretation of the seventh commandment:

Do not commit adultery. Would-be spiritual teachers . . . always need to be aware of human weakness, their own before that of all others. Sexual energies are always there when we flesh-and-blood humans interact with one another, anywhere this side of Eden. Check yourself always. Be aware; know your boundaries. Precisely because good teaching is an act of love, the teacher is always in danger. Make sure that all your giving is for the sake of those who seek to receive it, not just fulfilling your own unspoken needs, sexual and other.

What we are hearing here is, I think, an effort to counter the problem of sexual mischief that has arisen from time to time in the spiritual precincts of Renewal or Neo-Hasidic Judaism with which Green is well acquainted. And it is in itself unobjectionable. But is this admonition sufficient?

There are dangers lurking in the kind of rhetoric that Green and like-minded thinkers employ. When Green urges, for instance, that we must “let others know that we and they are part of the same One when we treat them like brothers and sisters, or like parts of the same single universal body,” he is perhaps contributing to the arousal of energies that may prove difficult to control. The dismissal of clear legal norms as nothing more than a transitory response to a wordless call, or the replacement of a firm prohibition of adultery with nothing more than self-selected boundaries (“make sure that all your giving is for the sake of those who seek to receive it”), is a failure to reckon with the power of temptation and the function of law, human or divine.

Compared with Green’s God and his Torah, Green’s Israel seems more familiar. It is still the people descended from Abraham. But it exists in some tension with what he calls “my Israel.” The latter consists of the people he describes as “you for whom I write, you whom I teach, you with whom I feel a deep kinship of shared human values and love of this Jewish language.” Green admits, “(partly in sadness!) that it no longer suffices for me to limit my sense of spiritual fellowship to those who fall within the ethnic boundaries that history has given us.” He is, indeed, prepared to say:

I have more in common with seekers and strugglers of other faiths than I do with either the narrowly and triumphally religious as the secular and materialistic elements within my own community.

Thus Green calls for a broader “Israel,” imagining “an extended faith-community of Israel, a large outer courtyard of our spiritual Temple.”

Although Green himself is a person who is clearly attached to the Jewish people, the logic of his position is disturbing. It leads him to privilege people possessing the proper spiritual consciousness, “my Israel,” over the actual people of Israel. When Green lectured a decade ago at the Pardes Institute, where I am the current director, he spoke beautifully of Yehudah Aryeh Leib Alter’s ahavat Yisrael (his love of Israel, or solidarity with fellow Jews), but I find no doctrine of ahavat Yisrael in Green’s radical theology.

Where does the State of Israel fit in this picture? Green acknowledges that it is necessary for Jewish survival, both now and for the foreseeable future, but it has no real place in his Judaism. Green defines himself as a secular Zionist, which is astonishing, because nothing else in his book is secular. Every mosquito, rock, indigenous religious practice, every person, place, or thing, is given a spiritual status. The “Jews of the Diaspora” (Green proclaims the “Exile” to be over) have the spiritual dignity of meeting God out “in the field” and of gathering the “divine sparks” as their moral voice continues to shatter idols. But Israel is presented as an abstract entity, lifeless, as if there are no “Jews of Israel.” Green does not share in his teacher Heschel’s notion of Israel as “an echo of eternity.”

The State of Israel is, for Green, something of a problem, probably because Israel is always also about survival, making messy choices, taking risks (above all, for peace) and sometimes not (for the downside is the abyss). Thematically, all this runs counter to Green’s hopeful evolutionary narrative, and to where he believes the evolution of Jewish consciousness in particular should take us. Israel exposes ruptures in “the unity of reality” in ways stark (we have enemies), necessary (we need to survive), and human (sometimes we do well and sometimes we don’t). It just doesn’t fit into his sunny evolutionary spiritualism, so he calls it “secular” (read: virtually non-existent).

Green’s God of Evolution is a jealous God. It devours the personal God of the Bible and the Rabbis, and spits out all parts of the Torah that are not conducive to the worship of “the unity of being.” It denies the election of Israel and denies the spiritual significance of the people of Israel’s resurrection and first experience of autonomy in two millennia. Pursuing the logic of its insatiable appetite for “Oneness,” it may even consume Green’s own platform of radical Neo-Hasidic Jewish mystical learning and practice as being too particularistic. After all, there may be faster and more direct approaches to the Source available in the constant hum of the universe. And what is a Jew to do then?

Suggested Reading

Killer Backdrop: A Rejoinder

Amy Newman Smith clarifies her position.

Moses, Murder, and the Jewish Psyche

Sigmund Freud had always identified with Moses. At the end of his life, as the Nazis rose to power, he returned to the Bible and the origins of the Jewish psyche. We all know his scandalous theory—or do we?

The Many Dybbuks of Romain Gary

Romain Gary—a Lithuanian Jew who regarded himself a Frenchman par excellence—emerges in a recent memoir as a master of self-invention and (just as immoderate) verbal invention, a chameleon of pseudonyms, a man of irreconcilable contradictions, divided against himself.

Screwball Tragedy

Picture a Jewish town, located deep in a Polish forest, that hasn’t received so much as a postcard from the outside world in more than a century. Max Gross conjured it up The Lost Shtetl: A Novel, and the result is both screwball and serious.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In