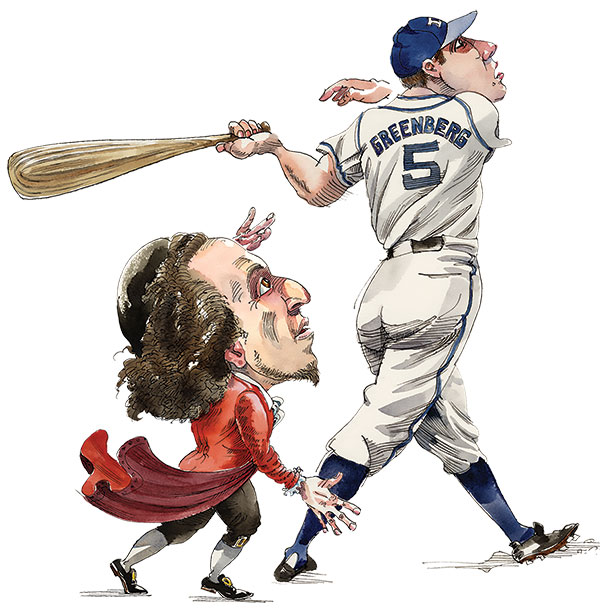

The Symbol Catcher

One of my favorite JRB covers features Hank Greenberg following through on a home run swing as he and the catcher, Moses Mendelssohn, watch the ball leave the park. The 18th-century philosopher and the 20th-century first baseman were both icons of breakthrough Jewish achievement and newfound, if incomplete, social acceptance. (They called Mendelssohn the “circumcised philosopher,” and it was received wisdom among sportswriters in the 1930s that Greenberg wasn’t “a natural.”)

That was the point of the cover—well, that and it was funny. But what our artist Mark Anderson and I talked about most was the specific baseball card feel we wanted to capture: Mendelssohn should look like Roy Campanella on the 1951 Bowman card, jumping out of his crouch, or, even better, like the catcher behind Carl Yastrzemski—was it Thurman Munson?—on the 1972 “in action” card as Yaz hits one down the line.

My best friends, Demian and Tom, and I started collecting baseball cards in the spring of 1975. The Topps company’s flat little wax paper packs had 10 cards inside and a thin, virulently pink, virtually unchewable slab of gum. Suddenly, we found ourselves involved in fine discriminations of value: Hank Aaron was an all-time great who had just broken Babe Ruth’s home run record (“Oh Henry!” went the television commercials), but Reggie Jackson was in his prime, plus he was on our team. We used the stats on the back of the card and whatever facts we knew or made up to argue and outsmart each other in trades, just like junior general managers.

In doing so, we took for granted that the connection between the cards and the players they represented wasn’t just arbitrary. A 1975 Hank Aaron card—which we would just call “a Hank Aaron”—was worth at least half a dozen Richie Zisks or Frank Tananas, but it was more—one might almost say deeper—than that. Baseball cards were, we knew, just little pieces of colored cardboard, but if you had an Aaron, a Jackson, or even a Zisk, you somehow had that player in a way that mattered. To what can the experience be compared? It was more like an art collector who shares in the artist’s genius by owning an original canvas than like a stockholder who owns an abstract share of a company. But it was even more like a religious experience, the purposeful channeling of a distant power.

If an authentic souvenir or player’s signature was like a holy relic, a baseball card was like an icon or an idol. That 1975 Reggie Jackson, which had a closeup of him, somehow participated in his Jacksonian essence (swinging, always swinging); it tapped into his unique Reggieness. In representing the god, the idol becomes a conduit for its power. We were, I think, as much little idolaters as we were junior GMs or future fantasy-league players. Indeed the cards, mere cheap cardboard and ink as a prophet of the game might have reminded us, became more important than the players themselves. We felt the pull and pleasure of an ancient temptation.

Moses Mendelssohn wasn’t an athlete (unless you count chess) and wouldn’t have been much of a catcher. He used to tell people that the curvature of his spine came from sitting bent over Maimonides’s Guide for the Perplexed as a teenager. However, he did have a theory of idolatry that helps explain something of the mystery of our childish intuitions about baseball cards. Drawing upon Maimonides’s account of the origins of idolatry as a conceptual error in the Mishneh Torah and Bishop William Warburton’s theory of Egyptian religion and hieroglyphics, among others, Mendelssohn told an Enlightenment story in which the evolution of written language led to regression in religion.

In my friend and editorial colleague Allan Arkush’s translation of the 1783 classic Jerusalem, or On Religious Power in Judaism, Mendelssohn posits a primitive ur-language:

The first visible signs which men used to designate their abstract concepts were presumably the things themselves. . . . Thus, the lion may have become a sign of courage, the dog, of faithfulness, the peacock of proud beauty, and thus did the first physicians carry live snakes with them as a sign that they knew how to render the harmful harmless.

This is obviously fanciful (though the rod of Asclepius as a symbol of healing, not to speak of Moses’s bronze serpent, clearly has something like this harmless snake idea at its origin). Mendelssohn’s real point is conceptual. Whether such a primitive state of affairs ever existed, “in the course of time” there was a process of abstraction: first “images of the things” replaced the things themselves, then “for the sake of brevity” came rapidly sketched outlines and, finally, further stylized hieroglyphics. Such abstraction made knowledge and its transmission possible, but “as always happens in things human, what wisdom builds up in one place, folly readily seeks to tear down in another.” In its progress from the thing itself to the abstract symbol, the sign became opaque, and this led to a new kind of religious error.

“The great multitude,” Mendelssohn writes, “was either not at all or only half instructed in the notions which were to be associated with these perceptible signs. They saw the signs not as mere signs, but believed them to be the things themselves.” Hieroglyphics made this both better and worse. They were plainly not faithful images of the thing they represented. On the other hand, the very mystery of an abstract glyph which could almost magically summon up its referent led to “all sorts of inventions and fables,” which were then, according to Mendelssohn, encouraged by the Enlightenment’s favorite villains, manipulative priests. “At all events,” he concludes, “one sees how this could have given rise to the worship of animals and images, the worship of idols and human beings, as well as fables and fairy tales.”

An idol, then, is a symbol whose referential function has been lost, misunderstood, or deliberately mystified. In an excellent book, the Tel Aviv University philosopher Gideon Freudenthal recently showed how this insight is at the center of Mendelssohn’s surprisingly sophisticated and powerful theory of religion.

In their combination of vivid imagery and abstract statistics, baseball cards were excellent little idols of heroic figures in the big-league pantheon, at least for a time. With the 21st-century advent of portable glowing screens, these little cardboard rectangles have become less and less popular with children, while becoming an even bigger business with adult collectors, who obsess over the quality of the card itself. Indeed, in a scandal that broke this summer, collectors alleged that a 1952 Mickey Mantle (one of the holy grails of baseball card collecting) had been fraudulently altered, essentially trimmed, to sharpen its edges. It turns out that the practice may be more widespread, and the FBI is investigating.

I doubt that such meticulous big-time collectors have retained the childish, mystical sense of possessing, or partaking in, the player himself in possessing his card. Baseball cards have become closer to commodities in themselves, or souvenirs (relics really) of a once innocently pagan childhood. Still, I’d love to have a 1934 Goudey Hank Greenberg.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

An Indian Play in Warsaw

Janusz Korczak couldn’t save any of his beloved orphans from the Nazis. Jai Chakrabarti imagines one, and sends him to India. It’s a great premise, but does it work as a novel?

Wandering Jews

Jews have been travelers since God told Abraham to get up and go. How deeply has this constant motion been imprinted on the Jewish psyche?

One Nation, Two Disraelis

In locating Disraeli within modern Jewish history, the late David Cesarani engages with a tradition that he traces back to Hannah Arendt and Isaiah Berlin, who placed Disraeli’s Jewishness at the heart of his private life, his novels, his political thought, and his career as a politician.

Nothing New Under the Sun

Elliot N. Dorff argues that numbers don’t dictate the strength of a movement, the power of its ideas do.

aaron bergman

As a lifelong Detroit sports fan, I can share with you one of the reasons we wanted cards from our own team was in order to give them strength, so maybe they would win occasionally. Maybe this is the same with idols. Idolaters wanted to give strength to their gods to beat the out of town gods.

Great article. Brought back a lot of memories of childhood and rabbinical school.