Diminished Light?

Kabbalistic literature presents its teachings as simultaneously original and ancient—milin hadatin atikin, in the Zohar’s memorable idiom. Those who embrace Kabbalah often do so in the belief that all contemporary mysteries and problems can be resolved, or at least understood, through the ancient wisdom it conveys.

In 1690 this belief was given expression in the posthumous publication of a slim tract by the English philosopher Anne Conway: The Principles of the Most Ancient and Modern Philosophy. Conway wielded pronouncements by “the Ancient Cabbalists” regarding such things as “the Ein Sof” (the Infinite) and “Adam Kadmon” (primordial Man) to resolve “all those Problems or Difficulties, which neither by the School nor Common Modern Philosophy, nor by the Cartesian, Hobbesian, or Spinosian, could be discussed.”

For Conway, the most crucial kabbalistic idea was that creation depends on the diminishment of God. As “the chiefest Good,” she explained, God desired to “make Creatures to whom he might Communicate himself: But these could in no wise bear the exceeding greatness of his Light. . . . He diminished therefore . . . the highest Degree of his most intense Light, that there might be room for his Creatures.” Although the original Hebrew term is not transliterated here, Conway’s book was the first to introduce the doctrine of zimzum (also spelled tzimtzum, tsimtsum, or imum) to the English reading public.

Of course, “diminishment” is just one of many options available to translators and interpreters of zimzum. The choices listed by Christoph Schulte in the opening sentence of his recent book, Zimzum: God and the Origin of the World, are “contraction,” “retraction,” “demarcation,” “restraint,” and “concentration.” The futility of reducing the meaning of zimzum to any one of these words attests to the conceptual ambiguity that envelops this doctrine in a veil of tantalizing mystery, much as zimzum itself simultaneously conceals and reveals the divine.

Conway regarded zimzum as an “Ancient Hypothesis of the Hebrews.” But Schulte locates the “origins” of this doctrine at the dawn of modernity, with Isaac Luria (1534–1572), the influential kabbalist known as the Ari. Although scholars continue to debate the pre-Lurianic history of zimzum, there is no doubt that it came to be seen as one of modern Kabbalah’s most emblematic ideas. Schulte ignores these debates and takes the attribution of zimzum to Luria as his axiomatic point of departure. From the Lurianic circle of mystics in Safed, Schulte follows the diffusion of zimzum as a key theological and cultural trope, circulating throughout Europe and eventually arriving in the United States.

Responsibility for Conway’s exposure to Kabbalah lies with Franciscus Mercurius van Helmont, a Flemish alchemist and Hebraist who collaborated with Christian Knorr von Rosenroth to publish Kabbala Denudata (Sulzbach, 1677–1678), a three-volume anthology of kabbalistic texts in Latin translation. Among these texts is another version of a book known to traditional kabbalists as Shaar Hashamayim, originally written in Spanish as Puerta del Cielo by Abraham Cohen de Herrera, a philosophical Jewish kabbalist from a Converso family.

Herrera led an adventurous life. In 1596, while serving as an emissary of the sultan of Morocco, he was captured by the English and released only after an exchange of letters between Queen Elizabeth I and the sultan. Earlier in the decade, Herrera was living in the port city of Ragusa (today Dubrovnik, Croatia), where he was schooled in Kabbalah by Israel Sarug, a direct student of Luria himself. In Puerta del Cielo, Herrera elucidates Lurianic Kabbalah in distinctly Neoplatonic terms, turning its mythical and anthropomorphic tenor toward a more rationalistic or philosophical mode of discourse.

There is no single authoritative account of what exactly Luria imparted to his disciples about God and creation. From the very outset, Schulte notes, zimzum was mediated via the competing “testimonials of his students”—most prominently, Chaim Vital, Joseph ibn Tabūl, and Moses Yonah, in addition to the aforementioned Sarug—who “not only transmitted but also simultaneously interpreted what their teacher had taught.” If Luria ever wrote something about zimzum in his own hand, it either hasn’t survived or hasn’t yet been discovered.

This very lacuna, the lack of an original text, may be one of the elements that has made zimzum such a generative site of speculation and argument. Indeed, Schulte’s colorful patchwork history shows that zimzum has been a constant conceptual preoccupation far beyond the networks of rabbinic scholars and pietists who considered themselves direct heirs to the kabbalistic tradition.

Zimzum’s cast of characters includes the celebrated scientist Leibniz in the seventeenth century, the philosophers Hegel and Schelling a hundred years later, and the Jewish “enlighteners” (maskilim) Isaac Satanow and Salomon Maimon. Closer to our own time, we encounter the Nobel laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer, the literary critic Harold Bloom, the actress and writer Ulla Berkéwicz, and artists such as Barnett Newman and Anselm Kiefer. Schulte also notes that a boat named Tsimtsum features prominently in Life of Pi (2001), a best-selling novel by Yann Martel later made into a blockbuster 3D film (2012). Along the way, we also meet Jewish scholars and mystics such as Shabbetai Sheftel Horowitz of Prague (the first to publish a version of the Lurianic zimzum in a printed book), the influential Italian kabbalist Immanuel Chai Ricchi, and the early Hasidic luminaries Shneur Zalman of Liadi and Nachman of Bratslav.

This is not an exhaustive list, but it gives some sense of the diversity and scope represented in Schulte’s Zimzum. Many significant gaps nevertheless remain. Most glaringly, there is no mention of Shalom Sharabi (known as “Rashash,” 1720–1777), who was born in Yemen; headed the Bet El Yeshiva in Jerusalem; and gave his name to an entire tradition of kabbalistic interpretation, literature, and practice that continues to flourish in the twenty-first century. The school of Eastern European Kabbalah originating at the end of the eighteenth century with Eliyahu, the famed Vilna Gaon (1720–1797), is also not discussed.

In addition to these lacunae, Schulte’s account often suffers from conceptual oversimplification and elision. His fleeting discussion of Conway is illustrative. In speaking of zimzum as a mere diminishment of God’s “Light,” she was emphatic that the space of the cosmos is “not a mere Privation” but a “real Position of Light,” albeit “diminutively.” Schulte quotes the relevant passage but makes no comment about the substance of Conway’s interpretation, which is deeply indebted to her reading of Herrera. Instead, he characterizes it as a “typical” example of Christian appropriation of zimzum to reconceptualize the doctrine of the trinity and the incarnation of the divine in Jesus. Rather than moving on so swiftly to other iterations of Christian engagement with Lurianic Kabbalah in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Schulte would have done better to linger a little longer on the theological, cosmological, and religious significance of Conway’s intervention. Failing that, he at least could have cited existing scholarship on her incisive contributions.

A 2004 biography by Sarah Hutton frames Conway’s understanding of zimzum as both a “barrier” and a “bridge” between the infinite God and the finite world. Atypically, this conception undermines the binary contrast between literal and metaphorical interpretations of zimzum, which Schulte often invokes but never probes. Amos Funkenstein once noted that the debate between Conway and her teacher Henry More over the “new” Lurianic Kabbalah was deeply bound up with the concurrent debate over the “new” Cartesian philosophy. He also points out that the differences between Conway and More partly anticipated the great debate between the early Hasidim and Eliyahu of Vilna over the meaning of zimzum and its consequences.

More recently, in A History of Kabbalah: From the Early Modern Period to the Present Day, Jonathan Garb argued that Eliyahu of Vilna’s reservations about divine immanence are reflected in his attack on the Hasidic insistence that divine vitality is found in “everything.” For Eliyahu of Vilna, like Immanuel Chai Ricchi before him, it is “divine providence” rather than “divine presence” that “can be found in the world.” Crucially, the origin of Hasidism as an autonomous school of Kabbalah can’t properly be accounted for without reference to this interpretive parting of ways with Eliyahu of Vilna, which ultimately hinges on the meaning of zimzum. If zimzum is a literal withdrawal, God has indeed vacated the space of the cosmos but providentially supervises it from beyond. If zimzum is a metaphorical concealment, God’s veiled presence simultaneously transcends and pervades all of created reality.

The theological and cosmological debate over the presence of God within the world has clear psychological and devotional dimensions too. On this score, Schulte insightfully highlights Hasidism’s interpretation of zimzum as a gesture of divine love, which invites a reciprocal response on the part of humanity. This encapsulates two key elements of Hasidism’s “innovative” reformulation of zimzum: First, “the anthropomorphic introduction of God’s [loving] joy over Israel as the impetus and motivation behind zimzum.” Second, the “humanization” of zimzum, as “a psychological, mental, spiritual act” manifest in “practical behaviors of self-retraction” and “acts of asceticism . . . which allow the pious both time and space for intensive study and prayer.”

Schulte has many fresh and illuminating things to say about zimzum’s role in the emergence of Hasidism. Disappointingly, however, he has nothing to say about any Hasidic thinker born in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He excuses himself by repeating the outdated claim that later masters owe their “charismatic authority” only to “hereditary lineage,” contributing nothing new.

“An in-depth examination of the notion of zimzum,”Schulte writes, “is not the place for personal entreaties.” Yet depth is precisely the price of his attempt to show no “favor” to one interpretation of zimzum or another. His account is formed through a series of snapshots that are accessible and interesting, but I often found myself wondering if a clear historical arc or argument would ever emerge. Such guileless narration comes, too often, at the expense of critical insight. Schulte’s unwillingness to take a stance leaves his Zimzum without an interpretive backbone, and the reader is carried forward only by the indefinite force of fascination.

Toward the end of the book, however, Schulte’s personal voice does begin to surface, and his historical view from nowhere is transformed into a rather generic twenty-first-century viewpoint: zimzum is a recipe for self-help and a metaphor for ecological restraint. Schulte calls this “the anthropology of zimzum,” arguing that “if we take [it] seriously, we will find that we ought to abandon the conception of creativity and productivity that seeks endless, permanent increase in performance.” He warns that such a path, “without breaks and without zimzum, ends in burnout and in the sterility of ideas.” Admitting that arguments in favor of ecological responsibility stand on their own merits, he nonetheless suggests that “zimzum as a conception of both cosmic and human restraint . . . can, but needn’t, culminate in the organic grocery store.”

For Schulte, the diminishment of zimzum’s enchanting vitality begins with a eulogy Gershom Scholem delivered for the philosopher Franz Rosenzweig in 1930. “The last zimzum,” he lamented, is the retreat of theology and its replacement with a set of secular theories. “The throne of justice,” he said, has now been handed “to dialectical materialism, and the seat of mercy to psychoanalysis.” In Schulte’s account, the association of zimzum with the “disenchantment of the world” was intensified by the philosopher Hans Jonas. In the aftermath of the Holocaust, Jonas argued, belief in God can be upheld only if zimzum is not only understood as a withdrawal of God’s presence but also as a withdrawal of God’s power: “The Infinite ceded his power to the finite [i.e., humanity] and thereby wholly delivered his cause into its hands.”

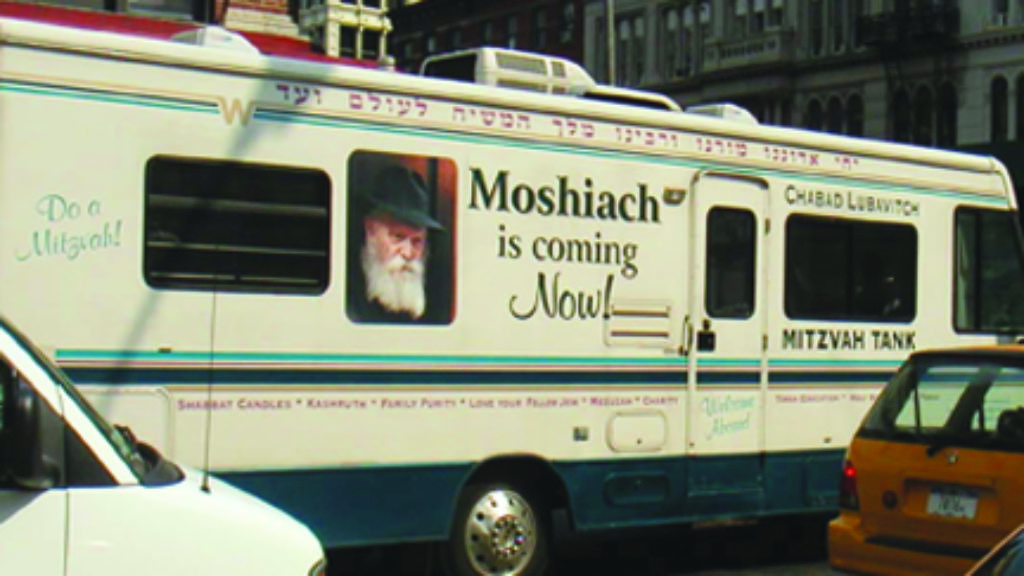

This is a familiar scholarly narrative in which the arc of history bends toward secularism. But zimzum was employed in the same period by very different thinkers to very different ends. Take, for instance, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the seventh rebbe of Chabad-Lubavitch. Schneerson taught that zimzum opened up the possibility of sin. In a turn that might be shocking to those unfamiliar with the radical rhetoric of Kabbalah, this locates the origin, or primordial root, of all evil in an act of God. Like Conway, however, Schneerson also subscribed to the belief that God is “the chiefest Good.” Accordingly, even a descent into evil must hold the key to an inconceivably greater ascent, which will somehow transform the darkness of zimzum into a manifestation of divine luminosity. As Gershon Greenberg has shown, Schneerson’s theory does not vacate God from history but instead grounds history in its redemptive divine potential.

As described by Schulte, another trajectory of kabbalistic disenchantment begins with Yehuda Leib Ashlag (1885–1954), who was born in Lodz and moved to Jerusalem in 1922. His fusion of “altruistic communism” with “Lurianic religious principles” interpreted zimzum as the divine “will to bestow,” which humanity is called to emulate, thus overcoming the “zeal for profit.” In a savage turn of history, Ashlag’s student Philip S. Berg (1927–2013) would later scrub all such “socialist political ideals” to create what Schulte aptly calls a “worldwide esoteric corporation.” This, of course, is the Kabbalah Centre, which “generates income . . . through merchandising, course fees, the sale of blessed Kabbalah water . . . candles, books on astrology . . . and even a Kabbalah energy drink!” Schulte places such “McMysticism” within a broader trend away from the “kabbalistic ghetto of esoteric rabbinical scholarship” and “in the direction of universal spirituality.” Similarly, he notes, the literary criticism of Harold Bloom (1930–2019) turns zimzum into an “ironic trope” and moves “out of theosophy into poetry.” In Ulla Berkéwicz’s short story Zimzum, the motif inscribed in its title stands only for the “emptiness” that pervades a “world of affluence devoid of meaning.”

Strangely enough, Schulte doesn’t seem interested in why these writers find this kabbalistic relic such an irresistible symbol of modernity. Even when cultural processes of disenchantment, materialism, and secularization empty zimzum of theological meaning, it somehow maintains its compelling power as a literary motif whose very emptiness gestures ironically, or perhaps mournfully, at the lost poetry of religion. Why?

Something like an answer can be found in the art and writings of Barnett Newman (1905–1970), a pioneer of abstract expressionism born in New York to Jewish immigrants from Łomża. Newman’s final sculpture, the monumental Zim Zum II, originated as an architectural synagogue design. Nevertheless, for Schulte it “is not a work of art with sacral connotations,” and its modernist minimalism can “only hint at the transcendent in its irrepresentability.” Yet Newman’s essays on the nature of art, and the notes he scrawled while working on his synagogue design, show that he understood zimzum as the crucial artistic element without which an “aesthetic object” can never be “subjectively” experienced as art. “Out of ZimZum,” he wrote, “was the world created. Only out in subjectivity can come the sense of exaltation.”

The “insane drive of man to be painter and poet,” Newman wrote, is nothing less than a drive to “return to the Adam of the Garden of Eden.” In this context, he explicitly cited Rashi’s comment that Adam wished to become “a creator of worlds,” just like God. The creative originality of art, according to Newman, occurs in the subjective experience of a divine exaltedness that is as new as it is old. To move out of theosophy, accordingly, would be to move out of poetry as well.

In a letter to the Hasidic painter Hendel Lieberman (1900–1976), Schneerson made a similar point: the artist and the religious worshiper are both trying to expose the “true light,” which zimzum hides beneath the surface of reality.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

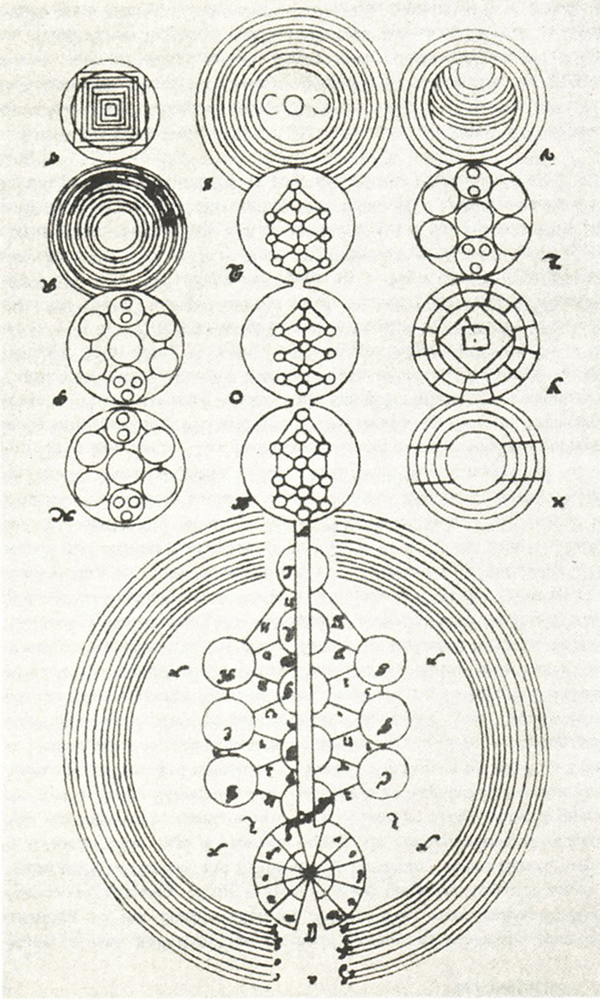

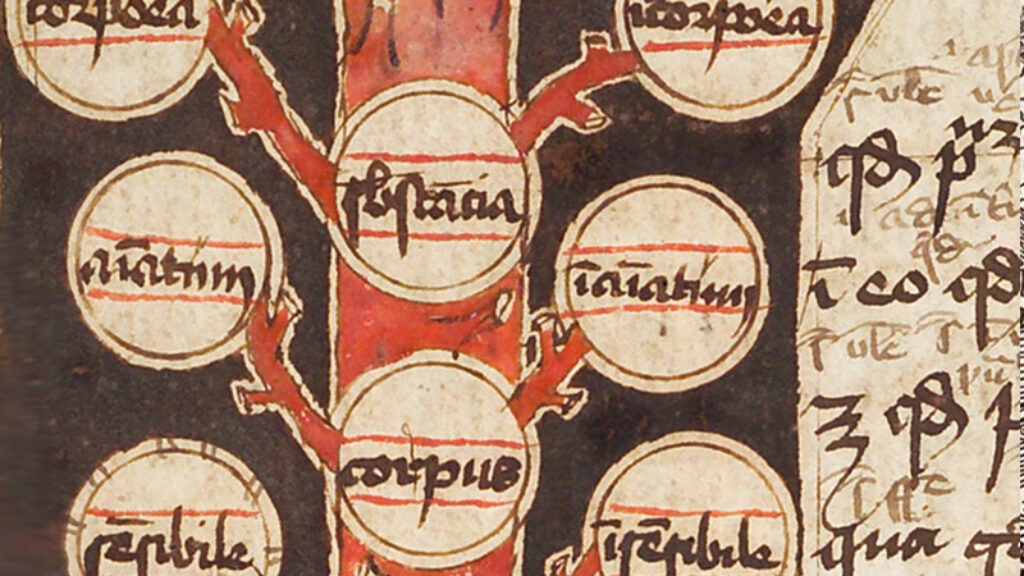

Roots in Heaven, Branches on Earth

Nothing sounds more idolatrous than drawing God. But that is just what a diverse bunch of medieval Jewish visionaries and scribblers set out to do.

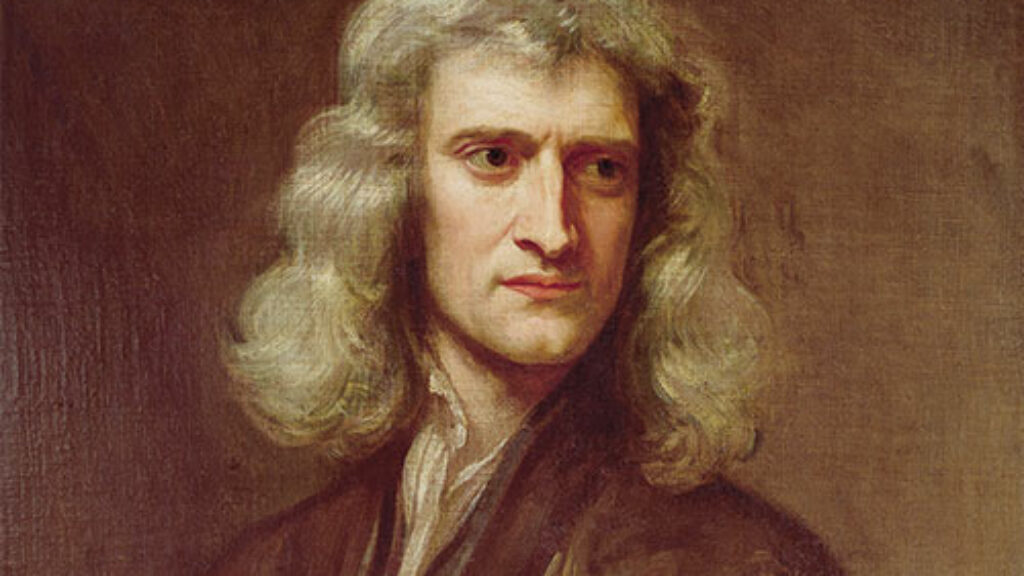

Maimonides, Stonehenge, and Newton’s Obsessions

It takes a bit of a genius to successfully study a genius, and in this case one must first master the millions of words Isaac Newton wrote about natural theology, doctrine, prophecy, and church history.

The Chabad Paradox

Despite its tiny numbers, the Hasidic group known as Chabad or Lubavitch has transformed the Jewish world. Not only the most successful contemporary Hasidic sect, it might be the most successful Jewish religious movement of the second half of the twentieth century. But two new books raise provocative questions about it.

Quarried in Air

Sefer Yeṣirah is the most influential Jewish book you never heard of. Indeed, it has been argued that early commentaries written on the book tilled the gnostic soil out of which sprouted the tree of Kabbalah.

gershon hepner

PARADOXICAL ORIGIN OF REALITY

Humankind, said Eliot, can’t bear much too much reality,

which surely is the reason why it focuses

on inanities, whose hocus-pocuses

circumlocute loquaciously this most inane locality.

Paul Celan expressed this by implying that life is a poem,

shrunk into nothingness, just like the German word Gedicht

reduced by means of Lurianic tsimtsum, to Genicht,

an irreality neologized to nothing as a noem.

Concept conceived by a creative kabbalistic curia,

tstimtsum’s program is enlightenment, the goal

of creativity a metaphor, black hole

the artistic product paradoxically proposed by Isaac Luria.