Quarried in Air

Friday afternoons in Sabbath-observant homes are a frenzy of cooking and cleaning. As the old adage goes, whoever prepares for the Sabbath eats on the Sabbath. Yet the Talmud tells of a pair of rabbis who regularly spent Fridays outside of the kitchen studying a mysterious work about creation. Luckily, these sessions also produced succulent meat, saving the good rabbis from hunger and, one would imagine, domestic discord. The identity of the rabbis’ magical text, known in medieval talmudic manuscripts as either “The Laws of Creation” or “The Book of Creation,” is unknown, but a text bearing the latter name—Sefer Yeṣirah in Hebrew—has circulated since the Middle Ages, and it is even more wondrous than any alchemist’s cookbook.

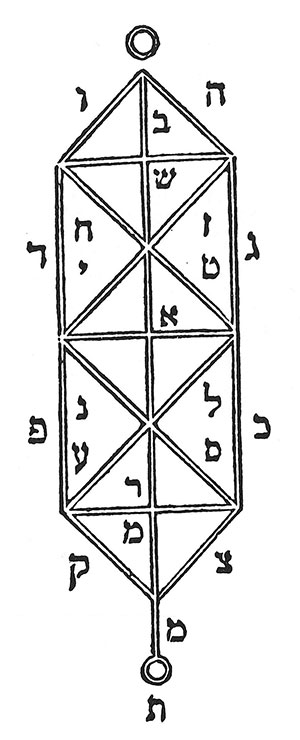

Sefer Yeṣirah is the most influential Jewish book you never heard of. Its many references to the decimal counting system, which it calls sefirot, gave us the central icon of Jewish mysticism—the 10 interlocking facets of the Godhead, which also came to be known as sefirot. Indeed, it has been argued that early commentaries written on the book tilled the gnostic soil out of which sprouted the tree of Kabbalah. At the same time, the text was creatively read against the grain by determined rationalists such as the 10th-century Babylonian rabbi Saadia Gaon, who understood it as disciplined cosmological speculation. And it inspired Gentiles, too, from Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz to Jorge Luis Borges and Umberto Eco.

What attracted this readership of kabbalists, philosophers, writers, and dreamers? For one, it was the book’s arresting thesis that the basic components of mathematical and verbal language, the letters and numbers that make up human speech and equations, are the very elements through which God fashioned the universe. At least as important is Sefer Yeṣirah’s idiom, which helped this obscure and extremely concise text—it weighs in at just a couple thousand words—secure a permanent place in the canon of Hebrew literature.

Indeed, what is most striking about it is its precise yet allusive prose, which somehow comes across as both scientific and sorcerous. This is apparent from the book’s opening lines, rendered here by the poet and translator Peter Cole:

Through thirty-two hidden paths of wisdom,

YAH, the Lord of hosts, engraved

His name—the Lord of Israel,

Living God and King of the world,

merciful, gracious God almighty,

on high and dwelling in eternity,

His name is holy

and He is sublime

and created His world

out of three words

sefer, sfar, sippur—

letter, limit, and tale.

Ten spheres of restraint,

Ten ciphers of Nothing—

And twenty-two letters at the foundation.

Scholars have demonstrated that SeferYeṣirah comprises two shorter works: a passage about the 10 generative numbers and another, more substantial treatise about the 22 procreative letters. These two courses in arithmetic and grammar conjure up a chiding homeroom instructor possessed of a poetic soul:

Ten spheres of restraint

ten, not nine or eleven—

fathom through wisdom,

be wise through knowing;

judge through them and with them search,

set a word straight

and restore the Creator to His place.

. . .

Twenty-two letters

carved through voice,

quarried in air,

and fixed in the mouth

in five positions:

certain sounds in the throat,

certain sounds on the lips,

certain sounds against the palate

and certain sounds against the teeth,

and others along the tongue.

As the book proceeds, it becomes clear that these Hebrew discourses on phonology and numerology have only the veneer of rationality. The text reveals one handbreadth while concealing another, urging its readers to “consider what a mouth cannot utter and what the ear cannot hear.” The prevailing image is of immensity and solidity emerging from a great void—“tremendous columns out of air that cannot be grasped”—which shimmers with peril:

Bridle your mouth and keep it from speaking,

your heart from wondering,

and if it wanders, return to the place.

In the introduction to his Sefer Yeṣirah and Its Contexts: Other Jewish Voices, Tzahi Weiss quips that after a century and a half of research, we know almost everything there is to know about Sefer Yeṣirah except the identity of its author, the time and place of its writing, the shape of the original text, and, also, its meaning.

The book is, in fact, devoid of identifiable markers. It appears suddenly in the historical record of the 10th century, and, unlike most surviving classical Hebrew literature, there are no rabbis named in the text. Tradition may attribute Sefer Yeṣirah to the patriarch Abraham, based on the book’s bizarre coda that describes how God set Abraham “in his lap, and kissed him upon his head . . . He made with him a covenant between the ten fingers of his hands . . . bound twenty-two letters into his language, and the Holy One revealed to him the secret,” but for philologists, that is neither here nor there. Many conceivable contexts have been proposed, ranging from 1st-century Jerusalem to the 9th-century Islamic world, but nothing near a scholarly consensus has emerged.

Weiss acknowledges his debt to the scholars who preceded him, those who edited the text from the medieval manuscripts, teased out its layers, and drew connections with other works. But he is still confident that he has something new and important to say. Like his subject, his monograph is brief, and Weiss gets swiftly to work by disclosing his chief hermeneutical assumption, which is that, “We have no reason to assume that it tries to conceal its context.” For Weiss, Sefer Yeṣirah’s lack of identifiers and its exclusion of named rabbis from the text are neither frustrating accidents of omission nor deliberate occlusions, they are clues that alert us to the text’s nonrabbinic origins.

It is true that the rabbis of late antiquity were passionate about the Hebrew letters, whether tallying their value and forging connections between numerically equivalent words in a still-popular language game known as gematria, or probing the shape of the aleph-bet for metaphysical meaning. Some rabbinic texts even ascribe creative power to the four letters of God’s ineffable name—the Tetragrammaton. Yet, as Weiss demonstrates, classical rabbinic literature does not share this text’s alphabetology, where all of the letters, from aleph to tav, make up a kind of divine periodic table. In the religious writings of late antiquity, this really can only be found in the Syriac Christian literature of northern Mesopotamia, where an ancient interest in the generative powers of the divine alphabet flourished, having overcome earlier opposition by Neoplatonists and Church Fathers.

Weiss contends that Sefer Yeṣirah applies the Syriac Christian alphabetology to the singular language of Hebrew. He argues that the text emerged from a barely known northern Mesopotamian Jewish community at some remove from rabbinic Babylonia, located to the south. If this is right, then Weiss has done more than locate the true origins of Sefer Yeṣirah, he has recovered the “Other Jewish Voices” of his monograph’s subtitle, voices that had been drowned out by the rolling waters and gasping wind of the talmudic sea.

Weiss includes the usual scholarly caveats that his theory is a theory and more research needs to be conducted. The thesis seems compelling, and Weiss may indeed have finally solved the problem of Sefer Yeṣirah’s original context. Yet, one cannot avoid the sense that Weiss’s straightforward scholarly detective work is a poor interpretive fit for a text that revels in mystery, repeatedly invoking its “ciphers of restraint” and “substance from Nothing.” It seems almost as if the author (or authors) knew that many centuries after the book’s creation, scholars would be disputing its original context and wanted to have some fun. Perhaps the text’s originators, who had incredible facility in an unusually sophisticated Hebrew, were not so distant from their playful scholarly rabbinic cousins after all?

A study of a book’s contexts looks not only for origins, but also at subsequent settings of reception, and Weiss does an admirable job retrieving the scattered evidence for how Sefer Yeṣirah was read in the first centuries of its existence. He reexamines late midrashim that mention the work, early commentaries that try to explain it, and explanatory glosses lodged in the text. He also considers Islamic parallels and a tantalizing reference in a 9th-century Latin epistle to Jews who “believe that the letters of their alphabet exist eternally and that before the beginning of the world they received different tasks.” For Weiss, all of this proves that the rationalist readings, which begin with Saadia, were thoroughly apologetic, rear-guard attempts at denying the book’s original mythic view of the world.

A lengthier book might have continued its review of Sefer Yeṣirah’s later contexts and considered the book’s appearance in Hasidic thought and in the writings of Christian Hebraists, early modern philosophers, and modern and postmodern writers. As is to be expected of a work written in exquisite Hebrew, Sefer Yeṣirah has had a fascinating afterlife in modern Hebrew literature. For one, Israel’s founding novelist, S. Y. Agnon, alluded to the book several times and, arguably, named the protagonist of his beloved A Simple Story Blumah after its great “nothingness”—blimah. The lovesick young man smitten by Blumah is so dumbstruck that the narrator, riffing on Sefer Yeṣirah, insists that we “consider not what his mouth utters . . . as the heart knows more than the mouth, and the ear hears what the mouth cannot say.”

Of the countless uses and abuses of this text over the past millennium or more, perhaps the most faithful adaptation has been achieved just recently. The self-titled album of the Israeli vocal artist Victoria Hanna includes lyrics taken from Sefer Yeṣirah, and its aesthetics realize the book’s embodied and evanescent view of language. Here, from the liner notes, is a translation of the beginning of the second track, appropriately called “22 Letters”:

Twenty-two foundation letters / Engraved in voice / hewn in wind / fixed in mouth in five places / In throat / In palate in tongue / In teeth in lips / Twenty-two letters he tied in his tongue / and revealed his secret / He drew them up in water ignited them in fire sounded them in wind set them on fire in seven / Led them in twelve constellations / Twenty-two letters / He engraved them / hewed them / weighed them / exchanged them / permutated them / And created with them the soul of all created / and of all future creation / He created substance from chaos / Made no-thing some-thing / Hewed great stones / From air that cannot be conceived.

Victoria Hanna is a stage name combining the names of the artist’s paternal and maternal grandmothers. The album Victoria Hanna, like Sefer Yeṣirah, is actually two works fused together, the first dedicated to her Egyptian grandmother Victoria’s holy and sensuous rebellion against her childhood marriage, and the other inspired by her Persian grandmother Hanna’s pious response to similar travails. (The artist herself was raised in what her website describes as an “ultra-Orthodox” Mizrahi community in Jerusalem.)

The “Hanna” section of the album is a collection of haunting melodies with lyrics mainly taken from the Bible and Jewish mystical literature, and the instrumentation soothingly frames Hanna’s incantation-like utterances. The “Victoria” collection pulsates with the frenzy of creation. Punctuating rap-like renditions of passages from Song of Songs, the Zohar, the Hoshanah prayers recited on Sukkot, and, of course, Sefer Yeṣirah are drums, horns, and strings, including zither and oud. Yet the most versatile instrument is the artist herself, not only her voice, which ranges across “oriental” scales, and her tongue and teeth, which hiss and click rhythmically, but also her entire body, which reverberates with Sefer Yeṣirah’s vision of simultaneously carnal and other-worldly language.

Victoria Hanna was released in 2017, after many years in which the artist toiled away in relative obscurity. She had spent time in New York, in association with the saxophonist and new Jewish music impresario John Zorn’s downtown scene, but she also traveled to the four corners of the earth, often performing for audiences who had never heard Hebrew before, let alone considered it the Adamic language of creation. Throughout this period, she experimented intensely with the language, breaking it down into its smallest particles and recombining them. Like the talmudic rabbis’ Friday afternoon study sessions, it was an arduous process of creation.

A few years before the album’s release, the first two tracks went viral and launched the artist’s now meteoric career. Of course, the popstar Madonna had already produced songs incorporating kabbalistic ideas and imagery, but there is no comparison between the profound depths of Victoria Hanna’s work and Madonna’s New Agey adaptation of third-hand mysticism imbibed at the Kabbalah Centre.

In “The Alphabet Song,” Hanna brilliantly embodies the instructive voice of Sefer Yeṣirah, teaching Orthodox schoolgirls the aleph-bet and its honeyed mysteries. The song “22 Letters” is also an act of instruction, though more for mystics in training than elementary-school students. Dressed in a dark and demure dress, the artist uses her hands to count, point, and mime the ways in which the Hebrew letters are grouped, where they can be found in the body, and how God “engraved them / hewed them / weighed them / exchanged them / permutated them.”

With her eyes wide open in awe, and her mouth working sonorous wonders, it occurs to me that in our generation, Sefer Yeṣirah resides nowhere more than in the person of Victoria Hanna.

Suggested Reading

Are We all Kahanists Now?

Shaul Magid attempts to show us how much contemporary Jews have inherited from a man most have tried to forget.

The Rebbe and the Yak

What do you do when your ancestor appears to you in a dream saying that he is trapped inside the body of a Tibetan yak? If you're the Ustiler Rebbe in Haim Be'er's new novel, you go to Tibet to find him, of course.

Samson Raphael Hirsch’s Attack on Liberal Christian Bigotry and American Slavery

In 1841, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch leapt into a raging debate between liberal and orthodox Protestants, declaring, “It is high time for the non-Jewish thinker to set aside convenient pre-judgements and to begin to construct Christendom without having to destroy Judaism.”

Everything Is PR

Peter Pomerantsev’s narrative of “the surreal heart of the new Russia” features pink heels, private helicopters, and fantastical Midsummer Night’s Dream parties with trapeze artists and synchronized swimmers dressed as mermaids.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In