Atlas Schlepped

The Russian terrorist Vera Figner, a leader of the group that assassinated Tsar Alexander II in 1881, recalled how she lost respect for her father when he replied to a serious question: “I do not know.” This answer filled the child with “burning shame.” All important questions, Figner knew, have clear answers, and all reasonable people accept them.

Figner didn’t weigh pros and cons. No sooner did she hear some indubitably correct answer than she adopted it. Regardless of counterevidence, she never questioned a belief, just as one never doubts a mathematical proof. Figner was by no means unusual. This way of thinking—this certainty about being absolutely certain—characterized both the prerevolutionary Russian radical intelligentsia and, after the Bolshevik coup, official Soviet thought.

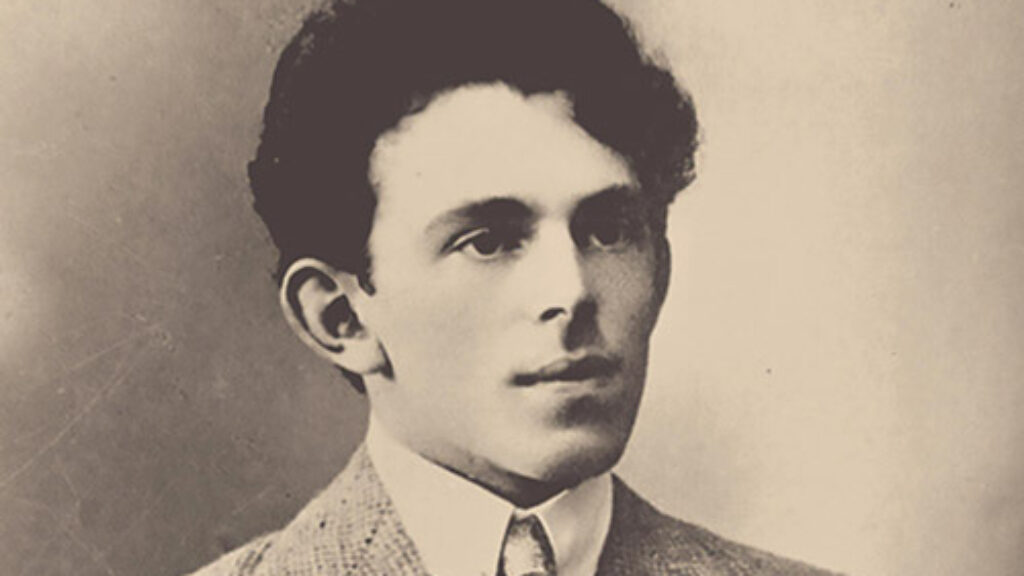

Born and raised in Petersburg, Alisa Rosenbaum—better known as Ayn Rand—shared this mentality. Though Jewish, her thought was Russian to the core. Rand’s fiction closely resembles Soviet socialist realism except for preaching the opposite politics. Call it capitalist realism. In the most perceptive article on Rand I have encountered, Anthony Daniels claimed, without much exaggeration, that “her work properly belongs to the history of Russian, not American, literature.”

In the 1950s and 1960s, Rand’s novels and essays achieved enormous popularity. Ayn Rand clubs sprang up on college campuses; a handful of influential figures, most notably Alan Greenspan, the future chair of the Federal Reserve, were at one time her disciples; and her books have sold tens of millions of copies. Although serious scholars and journals regarded her novels as devoid of literary merit, they felt obliged to argue with them. For a while, there was no escaping Ayn Rand.

Rand’s family was tolerably well-off and well connected; in her prestigious gymnasium, she befriended Vladimir Nabokov’s sister Olga. Rand never identified with Judaism and, after she arrived in America in 1926 assiduously avoided mentioning it. As Alexandra Popoff observes in a new entry to Yale University Press’s Jewish Lives series of short biographies, Rand routinely dismissed all questions about her background and insisted that interviewers discuss only her ideas. She never wrote about Jews. In her first novel, We the Living, set in Soviet Russia, the heroes and heroines all have Russian, rather than Jewish, names, while in her works set in the US, they bear American ones like “Howard Roark” and “John Galt.” As a young man growing up in the Bronx, I, like most other immature intellectuals, read and discussed Rand, but if anyone was aware of her Jewish background, no one mentioned it.

When I became a scholar of Russian literature, I immediately recognized Rand’s debt to the Russian radical intelligentsia. One can divide prerevolutionary Russian thought into two strongly opposed traditions: that of the radicals and that of Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Chekhov, and other great writers. The radical tradition featured ideologues and revolutionaries, including devoted terrorists like Figner and Sergey Nechaev; anarchists Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin; populists Pyotr Lavrov, Nikolai Mikhailovsky, and the leaders of the Socialist Revolutionary Party; Marxists like Stalin, Trotsky, and Lenin; and a host of tendentious literary critics.

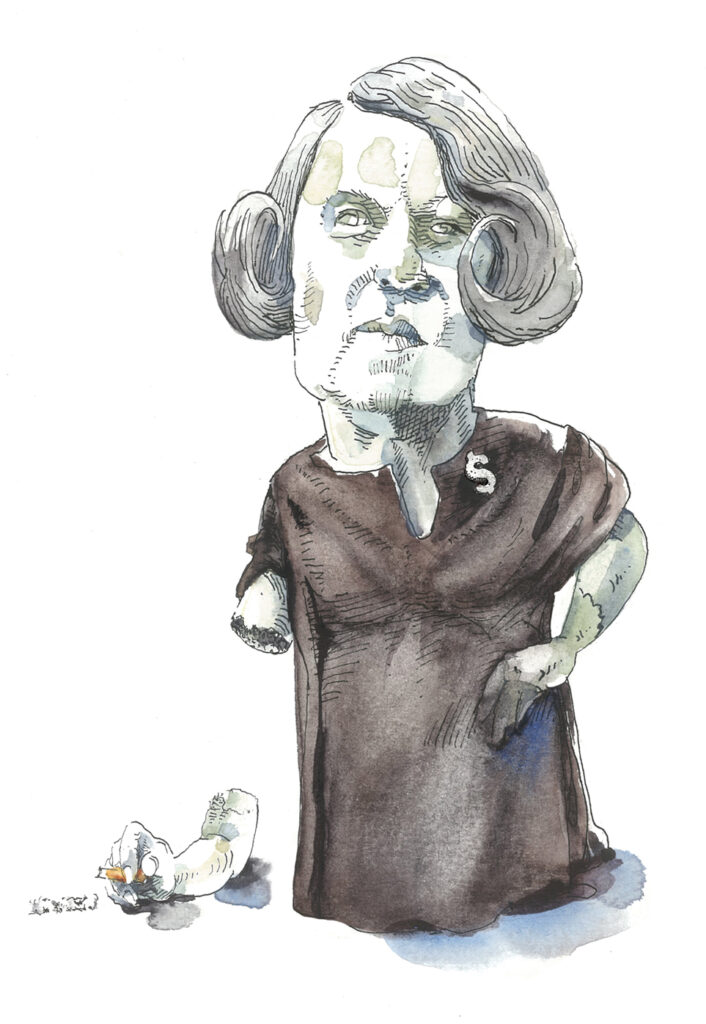

For all their disagreements about how to make a revolution and what should come after it, the radicals shared a reverence for Nikolay Chernyshevsky’s relentlessly didactic utopian novel, What Is to Be Done? The great writers disdained it. Dostoevsky savagely parodied it in Notes from Underground; Turgenev declared that Chernyshevsky’s style “arouses physical repulsion in me”; and Tolstoy dismissed Chernyshevsky as “that gentlemen who stinks of bedbugs.” All the same, What Is to Be Done? was by far the most popular book of the time, which every literate person claimed to have read. Young radicals even modeled their personal lives on the novel’s heroes and heroines, while Lenin deemed any criticism of the book “impermissible.” It became the model for Soviet Socialist Realism. Anyone who knows Chernyshevsky’s book will recognize its enormous influence, direct or indirect, on Rand’s fiction.

Where the radicals found everything simple, the great writers discovered ambiguity. Instead of certainty, they cultivated wonder at the complexity of people and the world. They knew that great art cannot be written to convey ready-made political messages. As the critic Mikhail Gershenzon observed in 1909, “the surest gauge of the greatness of a Russian writer is the extent of his hatred for the [radical] intelligentsia.”

Rand differed from the radicals on one key issue. For them, socialism solved all questions; for her, it was capitalism. In almost all other respects, their views coincided. Both embraced militant atheism and regarded religion as the main source of evil, for Marxist radicals because it was “the opiate of the masses” and for Rand because it preached “irrationalism” and altruism.

In Soviet thinking, radical materialism entailed a centrally planned economy presided over by an omniscient Communist Party. In rejecting government for “pure capitalism,” Rand was closest to the Russian anarchist tradition. There is no government in Galt’s Gulch, the utopian community of industrialists described in Rand’s last novel Atlas Shrugged. “We have no laws in this valley,” Galt explains, “no rules, no formal organization of any kind. . . . But we have certain customs, which we all observe.” The Soviet Union regarded Communism, symbolized by the hammer and sickle, as the ultimate social system. Galt’s Gulch features a dollar sign three feet high, and when Rand died, her body lay in a funeral home beside one twice that size.

Like Chernyshevsky and his Soviet heirs, Rand regarded her ideas as indubitable. As Popoff observes, she attributed all doubt to wickedness, much as Lenin deemed it counterrevolutionary. “Nothing in Marxism is subject to revision,” he insisted. “There is only one answer to revisionism—smash its face in!” Nobody except “bourgeois vermin” and “harmful insects” raised humanitarian objections, which Lenin characterized as “moralizing vomit.” For Rand, altruism was “absolute evil” and an opponent was “a parasite,” “a looting thug,” “a mooching mystic,” or “a metaphysical monstrosity.”

Rand’s abusive rhetoric appalled American philosophers. As Sidney Hook observed in reviewing Rand, “the language of reason does not justify references to economists with whom one disagrees as ‘frantic cowards,’ or to philosophers as ‘intellectual hoodlums who pose as professors.’ This is the way philosophy is written in the Soviet Union.”

The Soviets based their claim to infallibility on “science.” Marxism-Leninism, indeed, was regarded as the science of sciences, so that if theories in physics, chemistry, or biology ran counter to it, then they had to yield. Rand based her certainty on what she called “reason,” which is no more subject to doubt than “science.” Both Rand and her Soviet counterparts failed to grasp that what gives science and reasoned argument their persuasiveness is their openness to testing. They invite questioning and address counterevidence.

Rand’s reasoning was, in fact, remarkably sloppy. She regarded Aristotle as the greatest philosopher because he formulated the law of identity “A is A,” from which she claimed to derive a proof of radical individualism and the morality of selfishness. If A is A, then Man is Man and I am I, which (for Ran d) means that I owe nothing to anyone else. If Man is Man, then man must choose to survive, which means that it is irrational to let oneself be “looted” by unproductive people. If one is to survive, she reasoned, one’s ultimate value must be one’s own life. “The fact that a living entity is determines what it ought to do. So much for Hume’s question of how to derive ‘is’ from ‘ought.’” It is hard to say which is worse, Rand’s failure to understand the positions she dismissed or the shoddy logic she deployed in the name of infallible “reason.”

John Galt, the hero of Atlas Shrugged, deduces the objective morality of selfishness from another tautology, “existence exists.” “My morality, the morality of reason,” Galt argues, “is contained in a single axiom: existence exists—and in a single choice: to live. The rest proceeds from these.” No one could explain to Rand that tautologies can’t be used to prove anything about the real world.

Even more surprising, Rand, the defender of capitalism, seemed to lack even an elementary grasp of market economics. “When a man trades with others,” she declared in The Virtue of Selfishness, “he is counting—explicitly or implicitly—on their rationality, that is, on their ability to recognize the objective value of his work. (A trade based on any other premise is a con game or a fraud.)” But it is in Marxist economics that goods have “objective” value (the amount of labor it took to produce them). In market economics, value depends on preferences, including tastes, which have no objective basis, and on how much of the good one already has.

One reason Rand presumed that economic value must be objective is that in her view, everything valuable is. That is why she called her philosophy “Objectivism.” “Subjective” is for her a curse word, like “mystical.” After all, only what is objective can yield absolute certainty. That is also why she, like Chernyshevsky and the Soviets, insisted on the absolute reliability of our senses. Like Lenin, she seemed unable to distinguish between the claim that the mind shapes what we perceive and the denial of external reality.

Rand utterly rejected the idea that some issues are ambiguous or call for compromise. “One of the most eloquent symptoms of the moral bankruptcy of today’s culture,” she declared, “is a certain fashionable attitude toward moral issues, best summarized as: ‘There are no blacks and whites, there are only grays.’ . . . Just as, in epistemology, the cult of uncertainty is a revolt against reason—so, in ethics, the cult of moral grayness is a revolt against moral values. Both are a revolt against the absolutism of reality.”

Middle-of-the-road thinking is for Rand “the typical product of philosophical default—of the intellectual bankruptcy that has produced irrationalism in epistemology, a moral vacuum in ethics, and a mixed economy in politics. . . . Extremism has become a synonym of ‘evil.’”

Is it any surprise that Rand strongly appealed to bright teenage boys? As comic book writer John Rogers remarked, “There are two novels that can change a bookish fourteen-year old’s life: The Lord of the Rings and Atlas Shrugged. One is a childish fantasy that often engenders a lifelong obsession with its unbelievable heroes, leading to an emotionally stunted, socially crippled adulthood, unable to deal with the real world. The other, of course, involves orcs.”

With ambiguity and compromise characterized as moral treason, Rand’s novels feature principled heroes and dastardly villains, just like socialist realist fiction. In The Romantic Manifesto: A Philosophy of Literature, Rand argued for what Soviet theorists called “the positive hero,” the perfectly virtuous person who speaks the indubitable truth. Rand’s novels all contain such spokesmen, typically male, who display the physique of a Greek god, the nobility of a hero, and the charisma accompanying absolute self-confidence.

Rand distinguished this “romanticism” from its evil opposite, which she called “naturalism.” Naturalists (including those usually referred to as “realists”) describe the blemishes of the existing world. They focus on ordinary, fallible people. Instead of showing that reason and will can accomplish anything, they depict social forces and psychological dispositions limiting us. Such works are as bad as tragedy, which both Rand and the Soviets rejected as a genre based on falsehood.

When the “perpetrators” of naturalism “claim the justification that these things are ‘true,’” she advised, “the answer is that this sort of truth belongs in psychological case histories,” not in novels: “The picture of an infected ruptured appendix . . . does not belong in an art gallery.” The hero of The Fountainhead tells a sculptor: “I think you’re the best sculptor we’ve got. I think it because your figures are not what men are, but what men could be. . . . Because your figures are the heroic in man.” When Rand’s detractors call her work escapism, she contended, they are right only in the sense that medicine is an “escape” from disease. If such criticisms are allowed, “then a hard-core realist is a vermin-eaten brute who sits motionless in a mud puddle, contemplates a pigsty and whines that ‘such is life.’”

Realism, as opposed to Rand’s romanticism, is not just different but evil. As always with Rand, one way is right and all the rest are wrong. “Man’s soul—[the realists] proclaim with self-righteous pride—is a sewer,” Rand concluded:

Well, they ought to know. It is a significant commentary on the present state of our culture that I have become the object of hatred, smears, denunciations, because I am famous as virtually the only novelist who has declared that her soul is not a sewer, and neither are the souls of her characters, and neither is the soul of man.

I quote these passages to show why I experience Rand’s prose the way Turgenev experienced Chernyshevsky’s, as evoking “physical repulsion.” Her sentences are deliberately rebarbative, as if provoking anyone to dare disagree. The arrogant tone in which language stripped of nuance expresses the supposedly infallible truth creates one leaden sentence after another. Rand imagines her romantic prose soars, but it barely schleps along.

The Soviets justified their hostility to naturalism in much the same way. It is sick to focus on deformity. As Gorky explained to Vasily Grossman:

We know that there are two truths and that, in our world, it is the vile and dirty truth of the past that quantitatively preponderates. But this truth is being replaced by another truth that has been born and continues to grow.

The writer, Gorky concluded, must depict not vile reality but the beautiful ideal, not the visible present but the resplendent future.

Depicting the glorious future was supposed to bring it closer by a process that Herbert Marcuse, in his little-known study Soviet Marxism, compared to sympathetic magic. Describing something would bring it about. Literature therefore became an indispensable element in the Soviet project of remaking human nature. As Stalin famously explained, artists are “engineers of human souls.”

I could not help recalling this famous phrase, which Rand must have known, when encountering her defense of essentially the same position. “Why must fiction represent things ‘as they might be and ought to be’?” she asked. Quoting from Atlas Shrugged—Rand had an annoying habit of quoting herself or her fictional heroes as authorities—she answered: “As man is a being of self-made wealth, so he is a being of self-made soul.” In other words, she concluded, “Art is the technology of the soul.”

Both Rand and the Soviets believed that, without the aid of supernatural power, humanity will accomplish what had always been regarded as miraculous. There are no fortresses Bolsheviks cannot storm, declared Stalin, while Rand attributed the same power to unfettered capitalism. Enlightened by the right philosophy, human will can accomplish anything.

Setting aside “requiem Marxism”—patiently waiting for the iron laws of history to bring Communism—Lenin insisted that a “vanguard party” could hasten revolution. Once firmly in power, it could initiate what Engels called “the leap from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom.” Although Bolshevik voluntarism attributed extreme freedom to the collective, Rand ascribed it to heroic individuals. Volition distinguishes human beings from animals, and so, she reasoned, anything limiting the will reduces humans to beasts. History, culture, and tradition therefore exercise no power over true individualists, who entirely make themselves. As Howard Roark, the hero of The Fountainhead, proclaims: “I inherit nothing. I stand at the end of no tradition.”

It followed for Rand that there can be no innate—that is, unchosen—ideas. Neither can there be original sin or any inborn tendencies. John Galt calls such thinking a “monstrous absurdity” because either man is free or he isn’t; if his will is limited in any way, then he “can be neither good nor evil.” Had she read Darwin?

So insistent was Rand that behavior is entirely governed by will that when her long-suffering husband, Frank, developed dementia, she insisted on treating his lapses as voluntary failures. Daniels quoted from an earlier biography of Rand:

She nagged at him continually, to onlookers’ distress. “Don’t humor him,” she [said]. “Make him try to remember.” She insisted that his mental lapses were “psycho-epistemological,” and she gave him long, grueling lessons in how to think and remember. She assigned him papers on aspects of his mental functioning, which he was entirely unable to write.

Daniels, a psychiatrist, deemed Rand’s treatment of her husband “downright cruelty (as well as downright stupidity).”

In his review of Atlas Shrugged, Whittaker Chambers pointed to the remarkable fact that although there is a lot of sex in Rand’s (pre–birth control) novels, it never results in children. As Popoff astutely observes, “In Rand’s fiction families . . . are either not mentioned at all or abandoned. Mothers represent traditional values, which Rand renounced, and for this reason are portrayed as narrow-minded.” Members of Galt’s Gulch “have no families because raising children requires sacrifice at the expense of achievement.” Rand derived her ethics from the desire to survive, but if they were followed, humanity would soon die out.

Children require sacrifice: this obvious fact indicates that people are not, and can never be, fully independent. Rand’s heroes and heroines apparently arrive at adulthood without having gone through childhood, let alone infancy. It is as if she believed that, like Athena springing fully grown from Zeus’s head, people are created by sudden flashes of insight. My point is not just that infants are utterly dependent on another person and that children only gradually learn to take care of themselves. It is also that no one chooses when, where, and to whom to be born. Unlike Howard Roark, people always inherit something they did not choose.

Rand wrote as if poverty always resulted from failure of willpower, as if no one is born into it. She was right to reject the deterministic view that people are wholly the product of heredity and environment; choices that cannot be wholly explained by such factors help make us who we are. But it is no less mistaken to treat people as entirely self-made and utterly responsible for their condition.

Popoff, the author of a fine biography of Vasily Grossman, strains to justify the inclusion of her biography of Rand in a series devoted to “Jewish Lives.” “While it was previously assumed that [Rand] did not pursue Jewish themes,” Popoff explains, “this book will argue otherwise by revealing connections between Rand’s formative years in a traditional Jewish milieu and the stories she told in her books.” Rand may have tried to hide her Jewishness, but “writers cannot hide themselves in a literary text.”

Popoff detects Jewishness in Rand’s support of capitalism (and her dollar sign jewelry) because “when she spoke on behalf of American capitalists, defending ability, profit, and wealth, she was also fighting Jewish stereotypes.” If a Jew defending capitalists is fighting Jewish stereotypes, what would constitute endorsing them? In much the same spirit, Popoff maintains that Rand’s values are “merit-based” because they reflect “the notion of Jewish intellectual prowess.” Couldn’t there be other sources of merit-based values, including American culture itself?

The heroine of Rand’s first novel, We the Living, tells a communist friend: “You see, you and I, we believe in life. But you want to fight for it, to kill for it, even to die—for life. I only want to live it.” For Popoff, this passage shows that “the Jewish theme of choosing life is most perceptible in this novel.” It is true that the book of Deuteronomy advises its readers to “choose life,” but it is doubtful that Rand knew that, or would need to, in order to create a protagonist who was in favor of living.

The “intensely ambitious and uncompromising” protagonist of The Fountainhead, Popoff writes, “resembles the type of the ‘new Jew’ imagined by Zionists, who replaced Jewish powerlessness in the Diaspora with traits necessary to succeed in Palestine.” And he also resembles Henry V, Barry Lyndon, and Lord Jim, who are no less intensely ambitious and uncompromising.

As some reviewers of Rand’s novels recognized, and as Popoff stresses, Rand’s thought draws on Nietzsche’s idea of the superman. Just at this time, Popoff points out, Superman comics also achieved widespread popularity. Since the caped man of steel was created by two young American Jews, who were doubtless inspired by a desire to overcome “perceived Jewish physical inferiority,” Rand’s “attraction to a superhero stemmed from the same psychological craving.” Could Popoff have at least written “perhaps stemmed”?

According to Popoff, a Rand hero’s “remark that he is punished for his success and ability introduces an essentially Jewish theme,” as does “Rand’s 1961 lecture ‘America’s Persecuted Minority: Big Business.’” If persecution and unfair punishment are all it takes to indicate a Jewish theme, it would be hard to say what works don’t qualify.

As far as I am concerned, Jews should be grateful that Rand did everything possible to conceal her background. The less this terrible author of lifeless prose and repellent ideas owes to Judaism, the better.

Assign her instead to the Russian tradition, which features so many repellent thinkers that Rand’s ideas can cause no measurable damage. Neither can her fiction much diminish the glories of Russian literature. A canon including Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Chekhov can hardly be marred by a few puerile novels. Atlas Shrugged, remarked Dorothy Parker, “is not a novel to be tossed aside lightly. It should be thrown with great force.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Problems with Authority

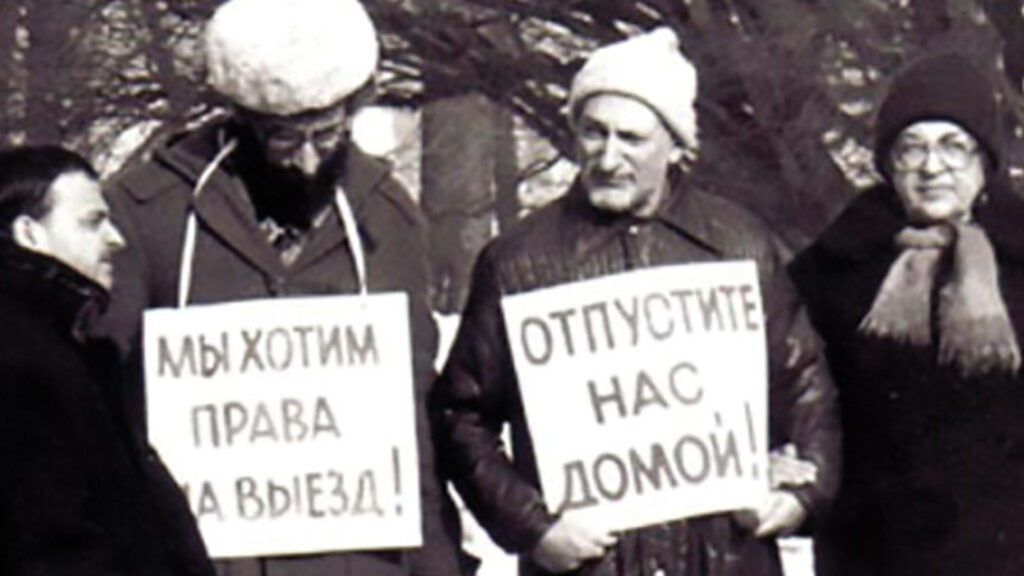

Paul Goldberg’s latest novel, The Dissident, is a narrative tour de force that plays far too fast and loose with the historical facts, leaving its readers deeply misled.

The Russian Joseph

Osip Mandelstam thought being a writer in the Soviet Union was “incompatible with the honorable title of Jew.” Stalin didn’t like Jewish writers in general and disliked the poem about his “cockroach mustache” in particular.

A Perfect Spy?

Was the original James Bond a Jew from Odessa?

From Hasidism to Marxism

The radical publisher Verso has re-issued Isaac Deutscher’s The Non-Jewish Jew: And Other Essays. But what is a “non-Jewish Jew”? And what was Deutscher?

mero

It is surprising that this long and otherwise comprehensive essay omits mention of Rand's infatuation with William Edward Hickman, a child killer who became a national sensation after sadistically killing and dismembering a 12-year-old girl in what Los Angeles police called the "crime of the decade" in the 1920s.

Rand worshipped Hickman's sociopathy: "Other people do not exist for him, and he does not see why they should," she wrote, gushing that Hickman had "no regard whatsoever for all that society holds sacred, and with a consciousness all his own. He has the true, innate psychology of a Superman. He can never realize and feel 'other people.'" This echoes almost word for word Rand's later description of her character Howard Roark, the hero of her novel The Fountainhead: "He was born without the ability to consider others." This contempt for any empathy for others extended to family as well. Rand wrote that feeling concern for family was as irrational and ultimately immoral as concern for persons in need.

Rand also famously despised democracy: "Democracy, in short, is a form of collectivism, which denies individual rights: the majority can do whatever it wants with no restrictions. In principle, the democratic government is all-powerful. Democracy is a totalitarian manifestation; it is not a form of freedom."

It's a wonder anyone still takes Rand seriously. "Objectivism" (which should accurately be named "Unconstrained Selfishness") is at best a study of the sociopathic possibilities of the human psyche. It is certainly not a moral philosophy. Absent the gullibility of college sophomores and its utility for a certain branch of right-wing politics, "Objectivism" would have withered and died as a cranky, immoral artefact of the early twentieth century, along with Stalinism and Nazism.