Like a Surgeon with a Scalpel, an Archaeologist with a Spade

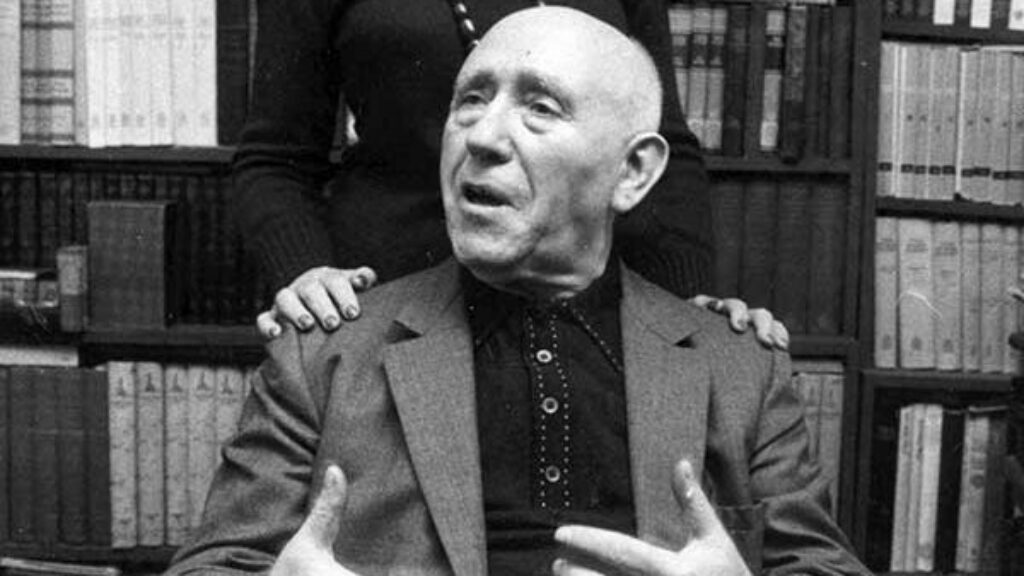

In 1968, a middle-aged Talmud professor named David Weiss Halivni was walking down 116th Street, near the Columbia University campus, when he came across a group of young people caught up in the student revolt. “When they noticed me,” Halivni later recalled, “they stared at me with disdain”:

I was the epitome of non-relevance. I offered them religious texts of two thousand years ago, philological and historical study, with minimal emphasis on social and political events. When they looked at me, they saw a relic, an antiquarian, and had little interest in what I taught.

Halivni may have been projecting his own insecurities onto the protesters, who likely saw him as just another Upper West Side academic going about his business (at the time, Halivni was a professor at the nearby Jewish Theological Seminary who moonlighted at Columbia). Yet the encounter still troubled him, and so he decided to do what he had always done when he faced hardship: “I will take out a Talmud and study. After I score a chiddush, an innovation, after I have discovered some new twist, I will regain my composure.”

There is more to this story, which was first published in a 1977 New York Times profile of Halivni, than meets the eye. At first glance, the professor’s reaction would seem to confirm the students’ criticism of scholars and scholarship as disengaged from the present moment. And yet, Halivni had courageously lived through some of the harshest moments in human history, when he was even younger than the protesters. Moreover, he wasn’t just retreating to the comfort of old books; he was looking for “a chiddush,” literally something new,but more than that, a revolutionary mode of reading a foundational text.

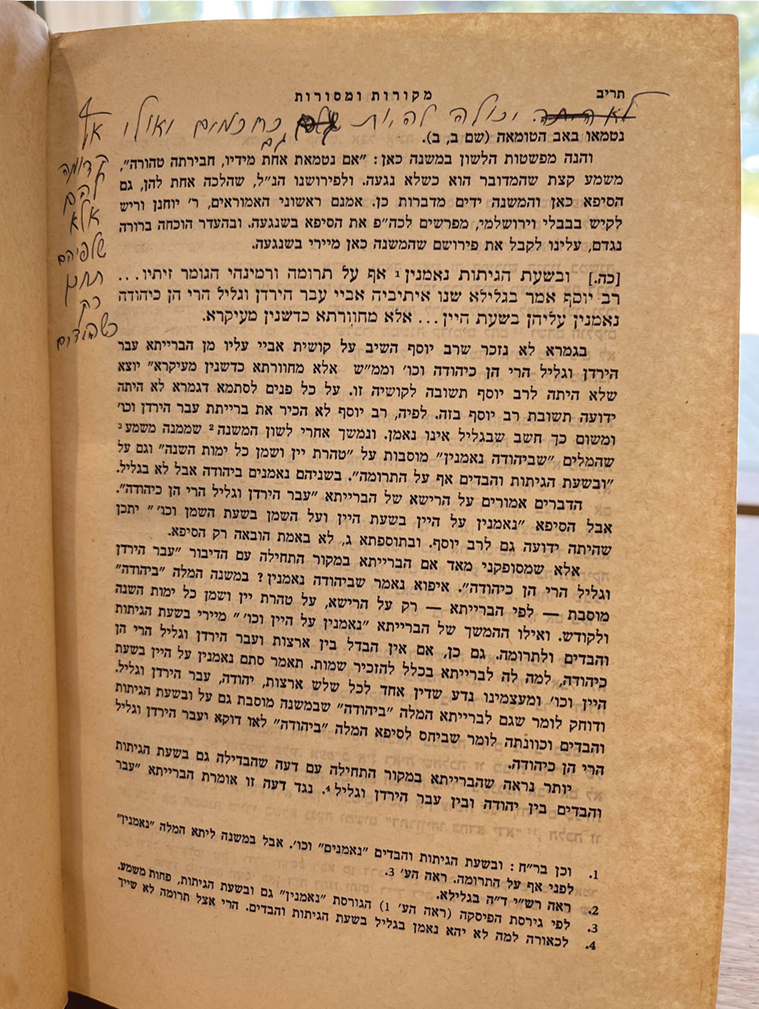

A year later, Halivni published Sources and Traditions: A Source Critical Commentary on Nashim, a Hebrew language commentary on seven tractates of family law in the Babylonian Talmud, one of the most puzzling and difficult texts of late antiquity. Apart from its terse Aramaic and serpentine argumentation, part of what makes the Talmud so challenging is its seemingly outlandish readings of the earlier rabbinic texts (preeminently the Mishnah), which it ostensibly interprets. “In our view,” Halivni wrote in his introduction, “the problem of forced interpretations (dihuqim)in the Talmud is a substantial one. Indeed, it is the fundamental problem of Talmudic research.”

Sources and Traditions would eventually grow to nine volumes, the last of which was published posthumously in 2023, the year after Halivni had passed away in Jerusalem at age ninety-four. In spending more than a half-century trying to answer the question of why talmudic arguments so often turned on unlikely interpretations, Halivni was not merely asking what motivated this or that talmudic passage; he was trying to explain the literary character of the bedrock text of rabbinic Judaism and his life.

David Halivni (a Hebraicized form of Weiss) was born in 1927 in Czechoslovakia but grew up in the Romanian town of Sighet, whose notables include the founder of Satmar Hasidism, Joel Teitelbaum, later an acquaintance of Halivni’s, and the Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel, who became his close friend. Halivni was lovingly raised by his mother and grandfather, a scholarly Belzer Hasid named Shaye Weiss, who was his first Talmud teacher. Soon, Halivni was recognized as an illui, or prodigy, a familiar figure in Eastern European rabbinic culture. Such recognition came with privileges, even cash prizes for stupendous feats of memory, and, of course, expectations. Once, when he was eight or nine, Halivni was out playing with other children in the neighborhood. A rabbi walked by and murmured that a boy who knows “Rabbi Chanina the priestly assistant”—the name of a notoriously difficult talmudic passage—shouldn’t be wasting his time with games. “I threw down the ball and never picked it up again,” Halivni later recalled.

Since the late Middle Ages, Ashkenazi culture had developed a set of scholastic methods, known as pilpul, which attempted to conduct virtually every line of the Talmud into a grand textual orchestra. The method had a reputation for impressive if textually footloose feats of interpretive creativity. Despite the prevalence of pilpul among Hungarian scholars, Halivni always preferred the more modest and reasoned approach taken by his grandfather. He sometimes told his students that as a child he had burst into tears when he couldn’t bring himself to accept the traditional commentators’ interpretation of a passage “because I felt that it was too convoluted, too forced.”

As a teenager, Halivni’s erudition became even more widely recognized, and he was ordained by one of the leading rabbis of Sighet at age sixteen. If this trajectory had continued, it is likely that he would have been swiftly married off and settled into a peaceful life of learning. But neither Halivni’s trajectory nor that of Hungarian Jewry Jewish life would continue. Sighet was utterly destroyed in the spring of 1944 when the Nazis asserted control over Hungary and deported the Jews to the camps.

Halivni was still sixteen when he arrived at the Auschwitz train platform, where Josef Mengele was separating those who would be sent straight to the gas chambers from those who would enter the camp. Like most healthy young men, Halivni entered Auschwitz. His mother and grandfather were murdered that day. Precisely twenty-four years later, he memorialized them in the introduction to the first volume of Sources and Traditions. Halivni’s father, sister, and aunt also died in the camps, along with virtually all of his relatives. “As for me,” Halivni signs off in his brittle, classic Hebrew, “I survived alone to tell, to remind, and to demand.”

Halivni was not only an illui, but a masmid, someone who was constantly studying Talmud. Even in a labor camp in lower Silesia, to which he had been transferred, he managed to teach his fellow inmates Mishnah. Two years after being liberated by the US Army, Halivni arrived in New York, where he ended up in Yeshiva Chaim Berlin, which upheld the traditional Lithuanian approach to Talmud study. After losing everything, Halivni was grateful to return to a life of intense study, but he was intellectually restless and remained bothered by those difficult moments when talmudic interpretation seemed to veer off course.

Despite the efforts of the Satmar Rebbe, Rabbi Aaron Kotler, and others to change his mind, Halivni decided to go to college. His first stops were the philosophy departments of Brooklyn College and New York University, where he hoped to learn how to apply philosophical rigor to the problem of forced readings. As he later wrote, he aimed to prove “that despite its seeming inchoateness, talmudic reasoning is based on objective and sturdy knowledge.”

Later, he moved still further from Rav Kotler and the Satmar Rebbe, who were attempting to reestablish traditional forms of Eastern European Orthodox life in America, and enrolled in the Jewish Theological Seminary. However, he did so principally to study with Saul Lieberman, who was not only the greatest academic Talmud scholar of the twentieth century but one who had himself been an Eastern European illui and was now recognized as a genius, if a problematic one, even within the yeshiva world. Lieberman’s melding of traditional Lithuanian Talmudism and philological rigor was an attractive model for the “illui of Sighet.”

In Halivni’s first book—an edition of an early Ashkenazi medieval Talmud commentary that had survived only in manuscript—he thanks Lieberman for “guiding me in the study of Torah according to its straightforward meaning.” But neither Lieberman’s famous rabbinic omniscience nor his impressive use of Greek and Latin literature to recover the missing literary contexts or lost allusions of rabbinic texts were eventually quite enough for Halivni. Lieberman’s approach left the problem of talmudic interpretation untouched.

Written in a modern rabbinic Hebrew sprinkled with frequent deferential caveats (“if I were not afraid, I would say as follows . . .”), Sources and Traditions is actually a fiercely independent work whose only loyalty is to interpretive truth and the integrity of earlier rabbinic sources. Consider Halivni’s treatment of the following mishnah and its subsequent talmudic interpretation:

A woman whose husband went abroad, and they came and said to her: “Your husband died,” and she married and afterwards her husband arrived—she must go out from this one and that one . . . [and is further sanctioned in a variety of ways]. And if she marries without authority—she is permitted to return to him [her first husband]. (m. Yevamot 10:1).

According to the first clause of the mishnah, if the first husband of a woman who was mistakenly led to believe that he had died returns, she can neither go back to him nor stay with the second husband whom she subsequently married. However, according to the second clause, “if she marries without authority,” she can go back to her first husband.

In explaining this mishnah, the Talmud claims that the key issue is the quality, or really, quantity, of the testimony: In the first scenario, it suggests the woman had relied on a single witness, whereas in the second case, two witnesses testified to her husband’s passing. Although Jewish courts accept the testimony of a single witness in extenuating circumstances, they want to make sure that a woman getting married on the basis of a single witness testifying that her first husband has died will also undertake her own investigation to confirm the report. Thus, the courts threaten to sanction her in the event of the first husband’s return.

This is a classic case of a forced talmudic reading of an earlier rabbinic text. The distinction between one and two witnesses is completely absent from the text of the mishnah. What is more, the mishnah’s first clause, which in the Talmud’s reading refers to remarriage on the basis of a single witness, uses a plural, rather than a singular, pronoun: “They came and said to her: ‘Your husband died.’” What is going on here?

For generations, traditional scholars took such inventive interpretations for granted as part of the Talmud’s unique discourse, or, as Halivni wrote, they perceived “these difficulties as illusory, as if deep study would somehow make them disappear.” Others, including modern opponents of Talmud study such as Jewish Enlightenment critics, “saw the Talmudic sages, especially the Babylonian rabbis, as lacking in simple and straightforward reasoning,” and they pointed to such unfounded interpretations as evidence of their shortcomings. In Sources and Traditions, Halivni showed that, on the contrary, the rabbis often displayed extraordinary interpretive skill. The problem was not that the rabbis were drawn to unlikely interpretations; it was that they were attempting to reconstruct lost traditions and the reasoning behind them.

What Halivni aimed to do in Sources and Traditions was recover original sources and their clear meanings, before they had devolved into that fuzzy category of transmitted wisdom called “traditions.” In the above example, after underlining the unlikeliness of the Talmud’s interpretation, Halivni rereads the mishnaic source and discovers that it isn’t talking about witnesses at all; it is simply distinguishing between a woman who contracted formal marriage with two different men and now must divorce them both, and a woman who thought her husband was dead and took up with a new partner “without authority.” That she subsequently lived together with another man does not impinge on the integrity of the first, and only real, marriage. Thus, Halivni clarifies the original meaning of the mishnah, while the Talmud’s understanding is shown to be a secondary, mistaken tradition, despite its canonical authority.

In Sources and Traditions, Halivni makes a great deal of his mission to recover the primary sense of rabbinic sources against later, defective interpretations. Of course, this was not an entirely new project. Some medieval Talmud commentators, like the towering twelfth-century Ashkenazi glossator, Rabbenu (Jacob ben Meir) Tam, noted alternative manuscript readings and suggested textual emendations. This practice became more pronounced among early modern talmudists, especially in the circle of the Vilna Gaon, who were willing to consider the simple sense of a mishnah against the standard talmudic interpretation. It was more fully developed in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, especially in secular academic settings. And yet, Halivni was unique among commentators in making the identification and untangling of farfetched talmudic readings his principal purpose.

It was this persistent focus on the exegetical misfortune of forced readings that led to Halivni’s theoretical breakthrough. In his second volume, published in 1975, he argued that the authority most responsible for the Talmud’s forced interpretations is what we might call its voice from nowhere—the interpretations, arguments, and remarks that are not attributed to any of the named talmudic rabbis who flourished between the third and fifth centuries, known as amoraim. As he put it in his introduction to volume two:

The work of this book is like that of the previous one . . . yet, in one significant matter I have changed my mind . . . and this is regarding the problem of the unattributed parts (stammot) of the Talmud. . . . See, it is perplexing! Close to half of the Talmud . . . is composed in an unattributed form, without naming who said what. . . . How is this unattributed half different from the other half in which the amoraim are named?!

As Halivni goes on to explain, the Talmud’s unattributed narrative voice is the work of later anonymous authorities who reframed the statements and interpretations of the amoraim.

This insight powers many of the readings in the later volumes of Sources and Traditions—for instance, Halivni’s interpretation of this passage from tractate Rosh Hashanah:

Rabbi Isaac said: Why do we sound the [shofar] blasts (toq‘in) on Rosh Hashana?

Why do we sound the blasts? The Merciful One says, “Sound the shofar blast [tiq‘u]at the new moon!” (Psalms 81:4)?! Rather, why do we blow staccato sounds (meri‘in)? Blow staccato sounds? The Merciful One says, “a memorial proclaimed with the staccato sound [teru‘a]” (Leviticus 23:24)?! Rather, why do we sound shofar blasts and staccato sounds while sitting [before praying the Amidah prayer], and sound shofar blasts and staccato sounds while standing [in the Amidah prayer]?

In order to mix up Satan.

This passage, with its persistent line of questioning and requestioning, its thrust and parry, is perfectly in keeping with the iterative, tennis-like rhythms of talmudic discourse. And yet, one must admit that it makes for an awkward read.

What, one wonders, did Rabbi Isaac really ask regarding shofar blasts on Rosh Hashanah, before the anonymous narrator rewrote his question again and again? And was it Rabbi Isaac or someone else who eventually brought in Satan? And what version of the question does the specter of a confused Satan answer? Finally, notwithstanding the biblical proof texts cited for blowing the different shofar sounds, why can’t we just take Rabbi Isaac as asking for the reason behind the mitzvah of blowing a ram’s horn on Rosh Hashanah?

Like a surgeon with a scalpel or an archeologist with a spade, Halivni summarily cuts away the entire middle section of the text and assigns it to the later, postamoraic period, when he believes the unattributed talmudic material was produced. What remains is a restored and remarkably clear source: Why do we sound the shofar blasts on Rosh Hashanah? In order to mix up Satan.

Rabbi Isaac was, in fact, interested in the reason for blowing the shofar at the New Year, which he explained had to do with confounding the forces of evil. This original question and answer must date to a time when rabbis freely discussed the reasons for the biblical commandments, unlike the postamoraic period, when such questions were less acceptable and Rabbi Isaac’s question was rewritten. Halivni has cracked this difficult passage open to reveal a beautifully simple earlier source, hidden underneath the husks of later rabbinic engagement.

This method led Halivni to a new approach to the Talmud’s formation:

It is upon us to see the Talmud as a compilation comprising two works, an amoraic work, and a work of the unattributed sections (ha-stamot), and they are distinct from one another in terms of language, method, and history.

Even when the attributed and unattributed strands are adjacent or interlaced, Halivni maintains that virtually all of the unattributed material—the stam ha-talmud, or more concisely, the stam—was produced independently by anonymous rabbis living after the amoraic period, whom he calls the “stammaim.”

According to Halivni, the amoraim were committed to transmitting their teachings concisely with as much precision as they could muster, while they saw the inevitably more complex reasoning behind these teachings as unworthy of preservation. It was only centuries later that the stammaim became interested in these dialectical traditions, which they now had to reconstruct on their own.

Thus, the talmudic material that frames, explains, and interrogates the transmitted sources of amoraic teaching was not produced by the named amoraim of the Talmud but by the stammaim, who chose to remain anonymous. In their work, the stammaim were presumably driven by a desire to correctly discern the original talmudic teachings, but, inevitably, they also had agendas and blind spots. Their work was ingenious, but it was also sometimes less than plausible. In a word, it was forced.

Buried toward the end of tractate Bava Metzia, in a brief aside claiming origins in the mysterious “Book of Adam,” is one of the few apparent reflections on the making of talmudic learning: “Rav Ashi and Ravina are the end of instruction.” Since the Middle Ages, this cryptic reference was taken to mean that these two leading amoraim of the late fourth and early fifth centuries were responsible for the editing of the Babylonian Talmud (medieval chronographers also posited that later figures, named savoraim, made additional, albeit minor, changes). By essentially ignoring Ravina and Rav Ashi and inventing a class of postamoraic editors, Halivni’s theory of the stam is wholly novel. Among traditionalists, it was regarded as blasphemy, a kind of documentary hypothesis of the Oral Torah, and almost as dangerous.

It was also controversial among Halivni’s fellow academics. Robert Brody, a Hebrew University professor who wrote a series of articles criticizing the sweeping assignment of the Talmud’s unattributed material to the postamoraic period, confessed in a respectful but critical letter to Halivni that he much preferred the first volume of Sources and Traditions, before the paradigm shift. Others were more biting in their criticism. In a talk delivered in the late 1970s at a conference celebrating Saul Lieberman’s career, the honoree directed some barely veiled criticism at Halivni, who was not only his former student but regarded by some as his successor at the Jewish Theological Seminary:

Do not give yourselves over to those incantations and sorceries aimed at removing all the difficulties with . . . claims that the Later does not understand the Earlier. . . . And pay no heed to those who gorge themselves on chiddush.

Halivni was undeterred. He continued to produce a new volume of Sources and Traditions every few years,in which, apart from the running commentary, he returned to the traditional sources on the formation of the Talmud to confirm, or at least not contradict, his historical model.

Halivni also began to raise up disciples of his own, a number of whom would go on to occupy prominent academic positions and apply their teacher’s approach to rewriting the history of the Talmud and rethinking its literary structure. A school began to take shape, and a workable mode of study, a textual methodology, or what in traditional circles is called a derekh ha-limud (way of learning), began to coalesce.

Early on in the project, Halivni spoke of his intention to write a definitive statement, on the stam and the problem of forced interpretations, when he had completed his commentary and had discussed all thirty-nine tractates of the Babylonian Talmud. However, he was already in his eighties when the seventh volume of Sources and Traditions came out in 2008, and he decided to release his historical findings as they stood. Later translated, annotated, and introduced as The Formation of the Babylonian Talmud by his distinguished student Professor Jeffrey Rubenstein, the book crisply details how Halivni saw things from the mountaintop.

Halivni argued that most of the editorial work of the stammaim did not begin until the eighth century, a full three centuries after Ravina and Rav Ashi. He also classifies the kinds of editorial tasks they took up. Among the stammaim in the Babylonian academies of the time, there were “reciters” who memorized the material, “joiners” who linked amoraic disputes, “gatherers” who assembled longer passages within the tractates, and “transposers” who performed an even greater variety of dynamic redactional work. Moreover, their activities were not coordinated. Not only did Ravina and Rav Ashi not edit the Talmud, as, in truth, had been known at some level even by most traditional scholars, but the Talmud was never really edited as a coherent work at all. As a result, passages produced by one group of stammaim often conflicted with those of another.

In the traditional rabbinic culture in which he grew up, a chiddush generally consisted of the clever reconciliation of apparently conflicting talmudic passages. Halivni’s historical meta-chiddush was that this was generally impossible: even passages that sat next to each other on the same page were sometimes from different hands. His final judgment—one often missed by academics more familiar with his early work—was that the Talmud was even messier than he had originally thought.

Halivni’s last two volumes continued to offer compelling readings of difficult passages. And yet, it must be conceded that these volumes, like the prior ones, suffer from defects in the project that were there from the outset. In particular, Halivni never established an accurate talmudic text upon which to comment. Although Sources and Traditions cites textual variants (mainly by way of Raphael N. N. Rabinovicz’s Dikdukei Sofrim, an important, nineteenth-century collation of such variants), it does so inconsistently. For instance, in treating a passage (Zevahim 18b) in which the chronology of the discussants is scrambled, Halivni solves the problem by reassigning part of an amoraic statement to the later stammaitic layer, without checking the manuscripts. If he had done so, he would have found a clearer version of the passage in a well-regarded medieval manuscript that would have rendered his textual surgery moot. (As it happens, the manuscript is held at Columbia’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library.)

Textual variants are not the only resources Source and Traditions cites with frustrating irregularity. Although Halivni frequently quotes a select group of earlier Talmud critics, like the German rabbi and historian Zecharias Frankel (1801–1875) and the Lithuanian-born founder of the Hebrew University Talmud department, J. N. Epstein (1878–1952), he is generally more interested in communing with classical medieval commentaries and Eastern European yeshiva staples such as the Maharsha, Rabbi Shmuel Eidels (1555–1631), and Jacob Joshua Falk (1680–1756), known in the yeshiva world for his famous work, Pnei Yehoshua.

It was clearly important for Halivni to remain in conversation with traditional rabbinic scholars. In a second edition of volume one, Halivni admonished them, saying that they ignored contemporary scholarship at their religious peril:

This second edition testifies to the fact that there are still Torah scholars who desire to study Talmud according to the critical, scientific method. . . . Today, Providence requires of us to be broader, to be more open. She has opened wide the gates of science . . . all for us to use. And whoever does not use it will have to answer for this.

Unfortunately, Halivni was sometimes himself guilty of the same sin.

In telling the history of talmudic research, Halivni and his erstwhile colleague from the Jewish Theological Seminary, Shamma Friedman, are often yoked together as equally dedicated to understanding the stam and its significance. But this is somewhat misleading. For his part, Friedman periodically refers to Halivni in his meticulous commentaries on three talmudic chapters, though nearly always in short footnotes and usually to make a local exegetical point. Yet in reading Sources and Traditions, which, by contrast, covers almost the entire Talmud, one would hardly know that Friedman’s work existed. Even when their commentaries cover the same ground, as in the first volume of Sources and Traditions, which begins with tractate Yevamot, and Friedman’s 1978 commentary on the tenth chapter of that tractate, they are like two colleagues passing in the night. Thus, the forced talmudic interpretation about a woman inadvertently marrying twice that vexed Halivni is not even commented on by Friedman.

The lack of overlap between the commentaries is telling. Friedman’s work is systematically devoted to the development of the talmudic text and not especially bothered by weird turns in talmudic interpretation. For Halivni, on the other hand, making sense of the Talmud’s forced argumentation is what propels Sources and Traditions across thousands of pages of Talmud.

Perhaps the most important difference between the commentaries of Halivni and Friedman has to do with their respective orientation toward the Talmud’s historical layers, its sources, and its traditions. Friedman is consistently dazzled by the creativity of the stam and clearly believes that its dialectical brilliance created the Talmud. Sources and Traditions is not really about the genius of the stam—it is about finding the pure sources beneath it.

To be sure, Halivni was also impressed with the rabbinic creativity of the stammaim, which he carefully documents. Indeed, in an unpublished letter, he criticizes Gershom Scholem’s belief that creativity in Judaism arises almost exclusively from mystical texts, rather than normative rabbinic ones. Halivni waxes poetic in describing how the rabbis emended earlier texts. “More than wanting to fix the text (which sometimes does not even need fixing),” he wrote, “they wished to shake the very foundations of the pillars of Torah and show their power and strength as partners with God in [creating] the Torah.” Beneath the prodding philology of Sources and Traditions, Halivni aimed to do the same thing.

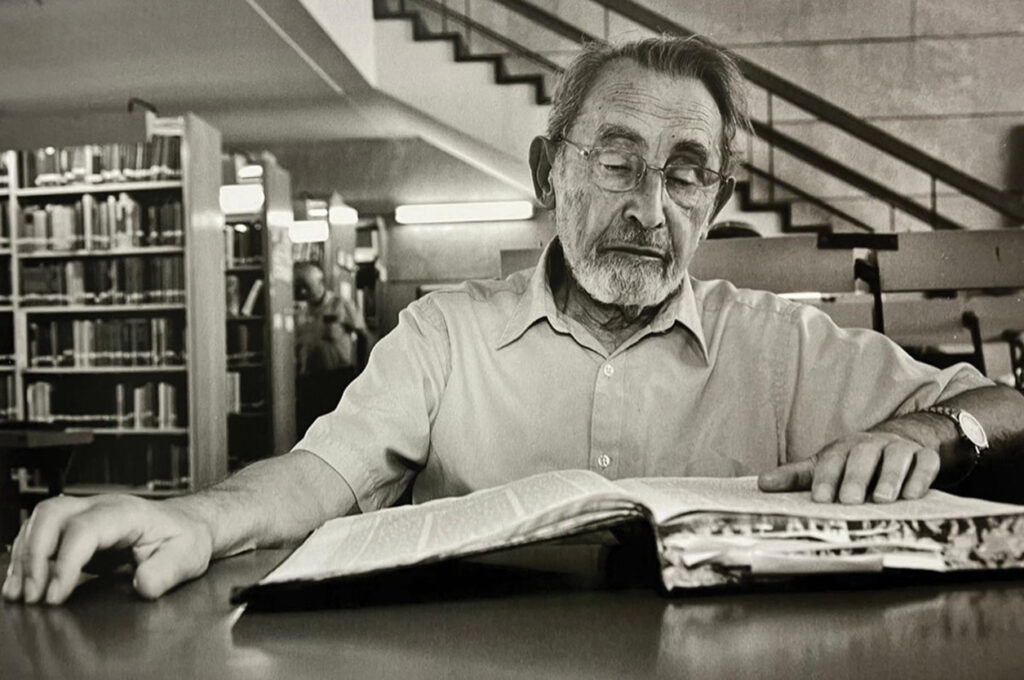

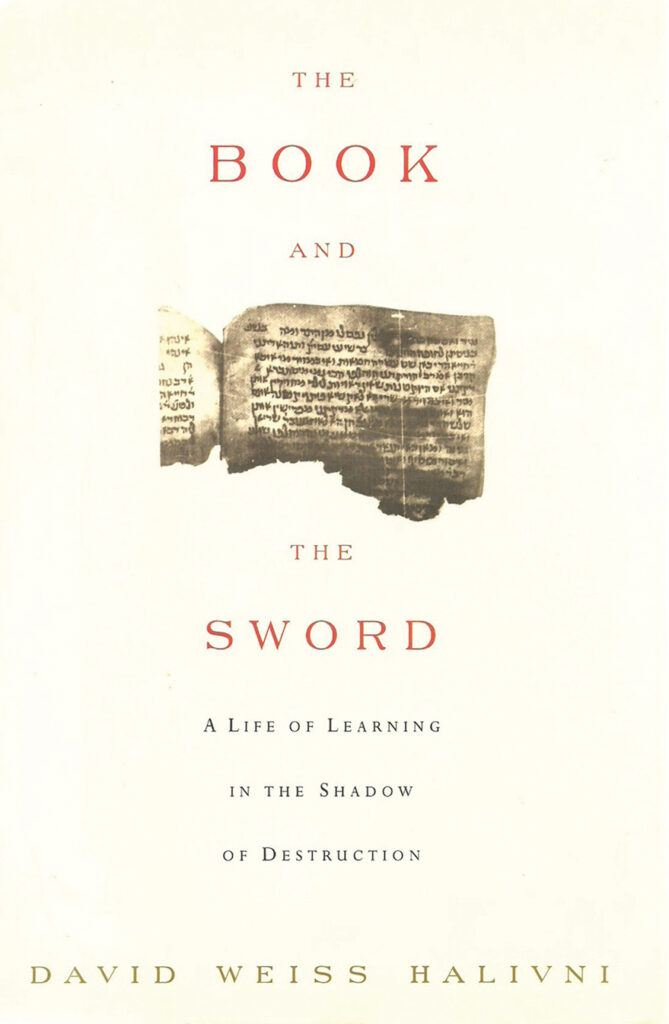

In his searing Holocaust memoir, The Book and the Sword, Halivni tells the story of a bletl, a page, from a good edition of Shulchan Arukh, the classic early modern legal code, which he rescued from the oily sandwich paper of a Nazi guard and shared with his fellow inmates.

The bletl became a rallying point. We looked forward to studying it whenever we had free time, more so even than to the phylacteries. It was the bletl, parts of which had to be deciphered because the grease made some letters illegible, that summoned our attention.

Textual recovery was central not only to Halivni’s life and historical scholarship but to his theology as well.

It would take Halivni decades to write about the Holocaust and its unfathomable losses. The Book and the Sword came out in 1996, and it was soon followed by a series of essays that culminated in Breaking the Tablets: Jewish Theology After the Shoah, published in 2007. Halivni was adamant in rejecting any assimilation of Churban Europa to traditional covenantal theodicy, which explains Jewish suffering as a punishment for Jewish sin. Instead, what Halivni tried to understand was the revelation of God’s absence that he had lived through, during which humans committed unfathomable evil unimpeded.

Part of Halivni’s answer is a dialectical model of Jewish history in which divine revelation briefly flashes into the world and constrains human free will. This is followed by an epoch of forgetting, in which the knowledge vouched by revelation disintegrates and must be restored with great difficulty. The postrevelatory moments are necessary and invigorating because they empower people to think, speak, and act freely. But such human expansiveness is dangerous, often concealing divine truth beneath human rhetoric and even lies. What is needed are talented, honest individuals, leaders like the biblical Ezra and the Mishnah’s Judah the Patriarch, who can recover the divine truth through human reason. In a way, the modern text critic, who comes to restore the canonical work and its original meaning, is their successor in this grand historical myth.

Although Halivni’s method was ignored or dismissed in the study halls of traditional yeshivas, he was, at his core, deeply traditional, not only a conservationist of the original meanings of early rabbinic teachings but a conservative with regard to their bindingness. This was apparent in his role in the controversy over the ordination of women at the Jewish Theological Seminary in the early 1980s. When the faculty voted to ordain women, despite his opposition (as well as that of Lieberman, who was already retired), he left for a position at Columbia.

Of course, Halivni’s halakhic opinions were irrelevant at Columbia, but he was widely esteemed there as a survivor from the lost world of European Jewry, and he worked hard to keep classical texts, particularly rabbinic works, in the university’s famous core curriculum.

Halivni flourished at Columbia. Yet he was not entirely reconciled to the modern American university. In remarks delivered at the convocation of Columbia’s eighteenth president, George Rupp, in 1993, he proclaimed:

May God grant you the wisdom to distinguish between free speech legitimately exercised as an inalienable human right and speech which is inciteful, intended to sow discord. Pander not to popularity, but take to heart public criticism.

Today, these remarks seem almost Delphic. Of course, Halivni could not have foreseen the inciteful speech that has engulfed Columbia and other universities since October 7, 2023. One wonders if he was remembering the student revolt of 1968. Halivni never answered those protesters, but his scholarship, which sought to recover the glow of truth buried beneath sometimes misleading torrents of words, was its own kind of answer.

David Weiss Halivni did not live to see Sources and Traditions to completion, but he came incredibly close. From the first volume produced in the heady 1960s to the ninth published in the tumultuous year of 2023, Sources and Traditions is a testament to what can be achieved in a life of intense textual study.

Of course, Halivni did not believe that he had resolved every forced interpretation in the vast sea of the Babylonian Talmud. The words—or to be more precise, the rabbinic abbreviation—upon which the last volume of Sources and Traditions closes are the classic rabbinic response to an unresolved difficulty: וצ״ע—“and it requires further investigation.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Tradition, Creativity, and Cognitive Dissonance

What are the conditions for a Jewish intellectual renaissance? Disagreement is one, inconsistency might be another; look at the early Zionists.

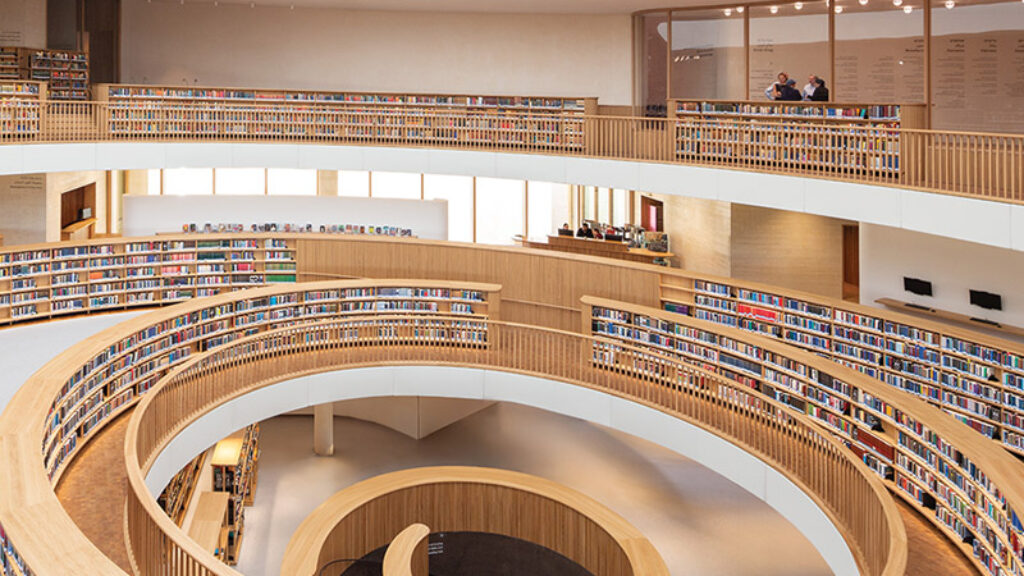

This Great House

Israel's new National Library is the most architecturally exquisite building erected in the history of the Jewish State. Like its predecessor, it’s also an excellent place to “hock” about books and ideas.

Chaim Grade: A Testimony

Toward the end of his life, the talmudist Saul Lieberman published his only Yiddish essay, an appreciation for his friend, the novelist Chaim Grade, the great witness to a lost world. Translated and with an introduction by Allan Nadler.

The People of the Book – Since When?

A new book seeks to overturn everything we know about the history of the Talmud.

gershon hepner

THE QUALITY OF REVELATION ISN’T STRAINED

The quality of revelation isn’t strained:

it droppeth on the gentle earth from heaven.

To say it doesn’t come from there might leave you pained,

and doubled up just like the richest cream from Devon.

About its truth all preachers hate to speculate,

believing it to be self-evident,

so inconsistencies that tend to maculate

the timbers of tradition that are bent

to harmonize its inconsistencies

are bypassed by the people who’re besotted

with old deceptions clothing Emperors

who have no clothes except those that are spotted,

seen only by the man who sense ignores.

Thus revelation’s quality depends

on readers who are forced to make a choice

between respect that till the bitter end

will fight derision, and a skeptic voice,

a process that demands far further

investigation than we generally provide,

though God, while heavenly, from earther

beings does not really hide,

a God who’s One and thus unique,

as we say in Shema each day,

wih us just playing Hide and Seek,

the game He seems to want to play.

Patrick Henry Reardon

Thank you so much for this fine introduction to a scholarly figure I did not know about. This entire essay was enjoyable and spiritually encouraging.

Leon Hoffman

I graduated Columbia College in 1963. I was pre-med with a minor in religion. One of the courses I took was "The Mishnah" with a Mr. Weiss and we used the Danby Mishnah.