Chaim Grade: A Testimony

In his deeply personal introduction to Saul Lieberman (1898–1983), Talmudic Scholar and Classicist, a rich memorial collection of essays about the great Jewish Theological Seminary scholar by students, family, and friends, Eli Wiesel recalled flying to Israel with Lieberman for the funeral of his wife, Judith:

He talked and talked, and I listened while he relived some episodes of his youth, Moteleh [the White Russian shtetl near Pinsk where Lieberman was born and raised] and Jerusalem, Nice and New York . . . this or that yeshiva . . . the various methods of [the yeshivot of] Volozhin and Novorodok, his stormy friendship with Gershom Scholem and his serene friendships with Chaim Grade, Louis Finkelstein, and Louis Ginzberg.

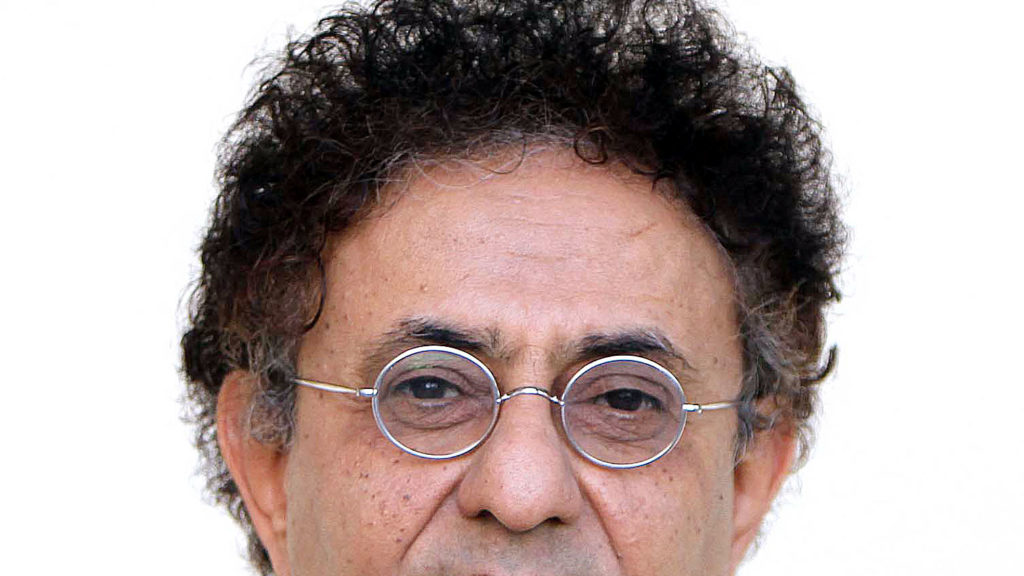

Both my eyebrows were raised after I first read this passage, 15 years ago: the left, because it was unimaginable to me that the great Yiddish writer Chaim Grade—as intense, prickly, and stormy a Litvak as I have ever known—was capable of serenity; the right, because, having myself been blessed with a lovingly turbulent relationship with Grade during the last five years of his life, I had only heard him mention Lieberman once. This was when I was chauffeuring him from his favorite Brookline hotel to Harvard, where he was giving an intimate seminar for a few Jewish studies doctoral students who were interested in Yiddish literature and culture. He remarked that he had two incentives to visit with Lieberman and his wife: First, of course, was Lieberman’s brilliance, and the “bonus,” as he put it, was the chance to enjoy a respite, however brief, from his wife, Inna. Often when I arrived to pick him up, he would rush into the lobby to prevent me from coming to their room, whispering, “Zogt ir az men geyt koyfen bikher” (tell her that we’re going to shop for books) since he knew she would have no interest in such an adventure.

Lieberman’s relationships with his academic colleagues are well known, but there is almost nothing published on his relationship with Grade, so I began to suspect Wiesel, unfairly as it turned out, of embellishment. But then, while thumbing my way through Grade’s books on my shelves, I saw the dedication in his collection of four novellas about the relationships between the rabbinical elite and the common Jews of der Litte (Jewish Lithuania), especially beggars and petty criminals, titled Di Kloyz un di Gass. (The English version contains three of the original four novellas and was published under the title Rabbis and Wives.)

This book is dedicated to Our Master, Professor Shaul Lieberman, for his deep friendship to the author, from a vanished world, filled with love of Torah.

It was not until my friend Yossi Newfield sent me a copy of a corrected typescript of Lieberman’s essay, which I have translated here, that I gave any more thought to the friendship between Lieberman and Grade.

Before leaving the traditional Litvak yeshiva world, Grade had spent a decade studying in the famous Novaredoker Yeshivas Beis Yosef, in which a demanding and austere form of ethics (mussar) was taught. He then went on to become the prized personal student of one of the greatest Lithuanian sages of the 20th century, Rabbi Abraham Isaiah Karelitz, who was known as the Hazon Ish, a figure he later fictionalized in his great yeshiva novel, Tsemakh Atlas (translated into English as The Yeshiva), as the Makhzeh-Avrohom. Lieberman was a product of the fabled, mussar-oriented talmudic academy of Slobodka, and the Hazon Ish was his maternal cousin. They were, in the deepest sense of the word, brothers from a vanished world, neither of whom ever ceased to be filled with love for that world’s Torah.

Most of the effusive praise that Lieberman heaps upon Grade has to do with how historically accurate his descriptions were. This stringent fidelity to historical accuracy was seen by many secular Yiddish literary critics as Grade’s most serious limitation. Lieberman recognizes his own friends and family, not least the Hazon Ish, among Grade’s fictional, but very realistic, characters. As one of the greatest and most demanding textual and philological historians of Greco-Roman-era Jewish Palestine, he regards Grade as a remarkably reliable narrator—more than equal to the finest historians—of the Jewish world of the Litvaks, especially its rabbis and yeshivot.

A word is in order regarding the climax of Lieberman’s effusive testimony. Despite the impression that Lieberman quite deliberately leaves about the circumstances of the American Academy for Jewish Research’s “unanimous decision to honor Grade in 1967, with a ‘citation,’” and a generous monetary prize, it is abundantly clear that Lieberman was the sole initiator of this effort, and it was he himself who wrote that encomium, or “citation,” which he quotes. (As Ruth Wisse amusingly put it to me recently: “Well, it certainly was not Salo Baron!”)

In the final two paragraphs of the essay, Lieberman compares Grade’s precise but decorous prose to that of other unnamed Yiddish writers who are tempted by the “cheap perfumes” emanating from sexual situations and ends with the suggestion that his friend remained a musernik. Here, Lieberman is clearly contrasting his friend with his rival, Isaac Bashevis Singer. Although it is unlikely that the editor of Di Goldene Keyt, Grade’s friend, the great poet Avrohom Sutzkever, would have allowed such sniping in his pages, it would appear from the orthography on the corrected document that it was Chaim Grade himself who struck the material from his friend Lieberman’s typescript.

This is, as far as I know, Lieberman’s only publication in Yiddish. It was published in Di Goldene Keyt under the title “An Eydus,” in 1980, and was translated and published in the American Hebrew magazine Bitzaron in the following year. This is its first appearance in English.

I understand that critics will challenge me with this question: “How dare a ‘dry scholar’ who examines ancient texts, documents, manuscripts, and other such archaic materials, presume to present himself as competent to offer an assessment of one of the greatest poets of our generation?”

So, I concede from the very outset that I do not present myself as a judge qualified to adjudicate, but merely as a witness who testifies simply by presenting the forensic data [he has] gathered. Moreover, a “dry” and honest scholar’s testimony might in fact be [even more] believable, because he will soberly declare all that is known, without resorting to fables and exaggerations. And, may I add, it seems to me that it might actually prove quite interesting to see how a man entirely free of any pretensions to being a literary critic will, in the end, evaluate Chaim Grade.

In 1946, while in Jerusalem, my brother, Meir, handed me a published little pamphlet [kuntres’l] of yellowed and frayed pages and said to me, “Read!” I thumbed through some of it and thought, “Nu? A poem. My brother knows that I will not while away my time only in order to read more mere poetry.” On the one hand however, the title, Musernikes, strongly interested me; a poem about the Novardiker musernikes? Really? On the other hand, it evoked in me a simultaneous sense of distrust. I could certainly understand an essay, a sober study, a “tragedy or a comedy,” or, of course, a satire. But who would write poetry about such a theme?

My brother was however adamant: “Do me a favor, and just read!” Nu? How can one deny a Jew a favor? Especially if the Jew is your own brother! And so, I picked up this little pamphlet and began to read with a smile. However, I very quickly sensed that the smile was beginning to escape my lips, just as I was becoming increasingly serious. I felt as if a dark cloud was enveloping me. Needless to say, I read it from beginning to end.

“Who is this character, Grade? And where is he now?” I then asked.

My brother, the longtime resident of Jerusalem, informed me that he had studied together with this very same Chaim Grade in Vilna, under the Hazon Ish.

“I have heard that his bones are scattered somewhere in Central Asia, to which he escaped at the outbreak of the German-Russian War, where he subsequently wandered” is how my brother Meir ended.

I felt a calling to perform an act of true grace [khesed shel emes, namely a proper burial] for this martyred poet. I certainly cannot follow his funeral procession; at the same time I can certainly eulogize him. The question however was before whom could I deliver such a eulogy? To whom could I even tell his story? My circle in Jerusalem consisted of scholars and professors, of the German cut, for whom all belletristic writing is akin to chametz during Pesach for a frum Jew. My entire life as a scholar consisted in, above all else, knowledge.

Moreover, as a scholar who only very long ago once indulged himself a bit in Russian, French, and English literature, I would have to bury myself deeply in this matter, were I to expect anyone to trust my research; this would be the very least prerequisite for me to expect readers to rely on my even being capable of such a sober investigation, without the smallest crumb of fantasy.

And so, I put aside and relegated this difficult matter, entrusting its secret to my wife, of blessed memory. I shared with her my uplifting experiences when reading Chaim Grade’s ballad. She clearly remembered this very well, as a full three years later, back in New York, my wife Judith approached me with a glowing smile on her face—“He’s alive! He has undergone a resurrection of the dead,” she proclaimed. “Who lives? Who has arisen?” I inquired, and she responded, “That very same Chaim Grade, of the musernikes, is alive! I just read in a Yiddish newspaper that in a few days there will be a literary evening honoring the publication of his latest book of songs and poems, Der Mameh’s Tzavo’eh “[a never-translated collection of post-Holocaust poetry published in 1949].”

A short while later we invited Grade to visit with us at home. At that time, he handed over to me a heavy pile of a half-dozen or so of his own books along with several large and thick, bound volumes consisting of selections from various Yiddish journals in which many of his other original writings had been published. The latter consisted exclusively of poetry, and so I immediately immersed myself in his verse and poems, which moved me deeply. Through his rich, lyrical depictions, Grade led me back, possessed and dreamily, to the villages of my childhood years, and through his poetic eyes I beheld them in their subsequent anguish and destruction. If, as the poets of antiquity instruct, the very finest aspect of any poetry consists in the muse’s lies, there has never in the world been any greater truth than in these very lies.

“Do you know,” my wife, of blessed memory told me, “that Grade’s prose doesn’t fall short, in any respect, of his poetry. Each week, he publishes either a short story or a chapter of a novel-in-progress in a newspaper. You must read them.” So, I began to read Grade’s prose in the weekly paper, and from that time on, I never skipped a single week. I was always eager to discover how every story would evolve and what would be the end of each tale. And I must confess that I never once guessed [the end] correctly, a sensation with which I was never comfortable, given all of my successful and scholarly forensic works and textual studies.

Such a gift, filled with all kinds of personalities and characters, with never a single one even remotely resembling any of the others! Such weird types, such as Vova Barbitoler in Tsemakh Atlas [translated into English as The Yeshiva], or the blind beggar Muraviev in Der Shulhoyf [The Synagogue Courtyard, untranslated] original characters that never once, even by coincidence, in any other of Grade’s works, are reproduced. And even when, if only superficially, they seem to resemble one another, say Mende the Cow of Der Shulhoyf and Elyokem the Shnit of Der Shtumer Minyen [The Silent Minyan, untranslated], they are fundamentally different one from the other. So too, the depictions of the women, say Rebbetsin Baggadeh in Der Brunem [translated as The Well] and

Di Graypeveh Rebbetsin, Pereleh, of Di Kloyz un Di Gass [translated as Rabbis and Wives], who in fact do not resemble one another at all, and neither of whom have any real equivalent or parallel in the world literature with which I am familiar. By contrast, even as each of the major figures in Grade’s work is so strongly unique, so are all the various masses, that he dubs “the street,” utterly undistinguishable from one another. This goes without saying; this is the essential nature of all “masses.”

Grade is adamant about this: The masses consist of small people, possessed with petty jealousies and hatreds, who love nothing more than to persecute and cause pain, deep pain, right to the marrow of the bone. Grade demonstrates the ruthlessness of these very same masses, who relentlessly move from one extreme to the next. And yet, whenever an innocent victim is plunged thereby into times of trouble, these masses suddenly become wrought with painful remorse; one accusing the other of having generated the suffering of this innocent, as the consequence of his wildly irresponsible rhetoric. One sees this theme overtly, over and again, in many of Grade’s tales; particularly in the constant battle between the “street” and the rabbinical elite portrayed most vividly in the novel, Di Aguneh [The Agunah].

By the time I got around to reading Tsemakh Atlas, I had already been stunned by the accuracy of Grade’s depictions. But in this work, aside from the central figure, Tsemakh Atlas, who is a literary creation forged by melding a variety of personalities, each consisting of numerous dispositions, I personally knew almost every one of the major “participants” in Grade’s yeshiva novel; [among others] Khaykl Vilner [Chaim Grade] and his rebbe in Tsemakh Atlas, the Makhzeh-Avrohom. The same is equally true of each and every one of the rabbis in Di Aguneh, who were all just like cousins of mine. I recognized all those family members whom in life I knew very well. And the same is no less true of the various yeshives with their numerous students that Grade vividly depicts. There is no one who could ever have possibly painted a finer portrait of them all!

Many volumes have already appeared about the muser movement and its proponents, the ba’alei-muser. You can choose to believe, or not to accept, these works. But once having read Grade’s depictions of these yeshives, you will know everything as if you had actually been there. Well before the full novel Tsemakh Atlas appeared in book form, I read one Friday a certain chapter in the paper Der Tog-Morgn Szhurnal a depiction of various young scholars from a variety of yeshives who are travelling during the summer vacation to a certain shtetl. I brought the newspaper with me to Dr. Louis Finkelstein, the chancellor of the Jewish Theological in New York City, who had a strong interest in life in the Lithuanian yeshives. “Take this and read. Take and read!” I declared to him. “And once you have read this over and again, and understood it, you will yourself have been there, in those very yeshives.”

Grade also describes the Jewish “street” of thieves and underworld characters. And I feel that Grade is not in the least less accurate and on-point in these portraits; above all, how characters of this sordid sort do remain, despite everything, Jews. Thus, in the novel Tsemakh Atlas there is this real character, Sroleyzer [a Yiddish conflation of the two Hebrew names, Yisrael and Eliezer], who is not just any ganef, but the “Rebbe of the Ganovim,” who was embroiled in a bitter conflict with the aforementioned Vova Barbitoler, at a time that Vova was the far richer of these two. However, after he fell into destitution, and began wandering around, publicly begging for petty donations, Sroleyzer—in the beis-medresh no less—publicly proclaimed that “even were Vova to have approached me and suddenly, with a steely fist, punched me right in the face, it would have been less shocking than seeing him in this degraded, sad state.” Sroleyzer ended up begging before his downfallen former enemy “R. Vova! Eat by me, sleep by me, and I will treat you as if you were my own, living brother.”

This ganef seemed to have forgotten that he was considered a rebbe only among the ganovim, and, at that very moment, he suddenly remembered, that he was also a descendent of Avrohom Avinu.

In 1967, the American Academy for Jewish Research decided, in a unanimous vote, to recognize Grade’s contribution to Jewish studies by honoring him with an official letter of commendation, or a “citation,” as it is known in the language of the foreign nations, together with a prize, in fact the largest monetary prize that had ever been awarded by the AAJR. Normally, the status of being a historical-critical academician does not entitle one to get involved in matters having to do with purely belletristic works. She [i.e., the Academy] limits her authority to scientific, scholarly works. And yet, in this case, “she,” namely these experts in history, had adjudicated and they decided that Grade’s works are of unmatched historical worth, as they considered them to be the most distinguished monuments to a vanished world.

And who really knows if this is not, in the end, what is most important about his work? For I speak not only of a poet and a novelist, but also of a man and a personality. One can, to be sure, find in Grade’s work some erotic themes. To cite just one example: in a “scene” from Tsemakh Atlas, a modest, young Jewish woman, Ronya, daughter of the shoykhet, is on the brink of demise; hardly a prostitute, Heaven forgive, nor a seductress, but rather a young, married, and most unfortunate woman, who happened, sadly, to fall in love—and become obsessed—with a man from her neighborhood, who happened also to be the director of the local muser-yeshiva. She was on the brink of suicide. But Tsemakh Atlas managed to emerge from this crisis tempted but unscathed.

Similarly, Chaim Grade does not tolerate pornography; at the same time, however, he is a master of detecting any hint, from subtle to secretive, of even the most esoteric erotica. He has a sensitive and sober appreciation for the subtle, flirtatious scent emoting from the daintiest of winks, and who detests the vulgar, overtly strong stench of cheap perfumes. He could very easily have found great worldly success taking advantage of his talents by depicting the most naked and raw elements of anguished human experience. Yet he resisted the seductions of, and the cravings for, all that cash that might come from translating his works and spreading his fame to the Gentiles. And so, one wonders, who overcame the greater test of will, Tsemakh Atlas or Chaim Grade?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Lost in Translation: Song of Songs and Passover

Why is this Targum different from all other Targums?

Brave New Golems

As monsters go, golems are pretty boring. Mute, crudely fashioned household servants and protectors, in essence they’re not much different from the brooms in the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” story.

Minyan 2.0

The next big thing in prayer.

Manufacturing Falsehoods

An immense echo-chamber has been built, and the line is always the same: Israel is not allowed to be a country like any other.

Michael Silber

Thanks Allan for once again recalling Chaim Grade's legacy. On the spur of the moment, I turned to Book Depository and then Amazon to order all his books in English translation only to discover that almost all are out of print. It would be a mitzva to undertake to have his works reissued.

gwhepner

MAKING THE GRADE IN YENNE VELT

The details of the Talmud often are fantastic,

and sexual passages may be explicit.

Though Singer's prose to it is paraphrastic,

he made what it condemned appear quite licit.

His characters live close to yenne velt,

where goblins, imps and devils set their traps,

resembling billiard balls that roll on felt,

regarding all the pockets as mishaps.

Asmodeus, Lilith, Machalath,

are dreaded by them far more than a wife,

yenne yenta who attacks with wrath,

with threats like: “Choose this world, or loose your life!”

Chaim Grade interestingly evaded

the strong stench of this Singer's cheap perfumes.

Although some passages of the Talmud are X-graded,

he fumigated all its sexual fumes.

[email protected]

ynew23

Saul Lieberman delivered the following tribute to Chaim Grade in 1970, in Israel, at the last session of the Eighth International Convention of the World Council of Synagogues.

The following is the full text of the tribute.

"I do not pretend to be a literary critic, but I do pretend to be a great reader, so I will present Mr. Grade to you as I, a reader, see him.

Mr. Grade began his literary career as a poet, and has written a great deal of poetry. I have read only a part of his poetry, for a very simple reason. When you begin to read his poetry, you become so excited sometimes that your heart comes to a standstill. So I have stopped reading poetry! On the other hand, I have read almost all his prose works.

Here again, I can only talk as a reader. The American Academy for Jewish Research, which is not a wealthy institution, gave Grade an award of $6,000, the largest grant given to a Yiddish writer. This Academy, according to its statutes, cannot give awards to writers of belles lettres, but they found that Grade's books have immense historical value. He writes about the past—not the far-removed past, but about the past that many of us still remember.

When you begin to read Grade's works, it is hard to stop. You feel that you are reading a masterpiece of genius. At the same time, it is so true and correct; it is a genuine picture of life in Eastern Europe. He describes almost all the layers of Jewish society: the underworld, the people's struggles, their relationship to the clergy—the importance of the rabbis, the people's complaints against and at the same time their reverence toward the rabbis.

Unfortunately, only people who know Yiddish well can appreciate the flavor of his language and through it savor the period of which he writes. While I do not pretend to be a prophet, I venture to predict that there will be a time when people will study Yiddish only for the purpose of reading Chaim Grade's works."