A Need for Roots

In the French edition of Simone Weil’s collected works published by Gallimard, a volume is devoted to “Family Correspondence,” consisting of letters Weil wrote to her parents, Bernard and Selma, and her older brother, André, a brilliant mathematician. These have now been translated into English under the title A Life in Letters, but what is most interesting and important about Weil’s life can be deduced from these letters only by omission.

Take the very last letter, dated August 16, 1943, eight days before Weil’s death, which her parents received after learning she had died. Writing from London, where she had gone to join the Free French movement, to New York, where her parents had found asylum after fleeing Vichy France, Weil actively concealed the truth about her dire situation. “Very little time and inspiration available for letters now. They will be short, spaced far apart, irregular,” she says, keeping up the pretense that she was still performing demanding but unspecified tasks for Charles de Gaulle’s government in exile.

In fact, since April, Weil had been dying of pneumonia, moving from hospital to hospice while telling her parents, “I’m still living nice and quietly in my room,” and assuring them, “Darlings—everything perfectly all right—nothing new.” Her death was so unexpected that André, who was also in America, decided to break it to their parents with a further ruse. He had a friend call Bernard and Selma to relay “worrisome rumors” about Simone, then delivered the news in person once the ground was prepared.

It was a fitting end for a correspondence sustained by affectionate dishonesty. In practical matters, Weil placed complete trust in her parents. In the 1930s, as she was drawn into radical left-wing activism, she peppered them with requests to send money to comrades, subscribe to party newspapers, and succor political refugees. “Could you, in the spirit of brotherhood, take care of this buddy—a real German worker, a qualified metal worker . . . who escaped from a concentration camp? . . . See if there are housing possibilities,” she wrote in March 1934.

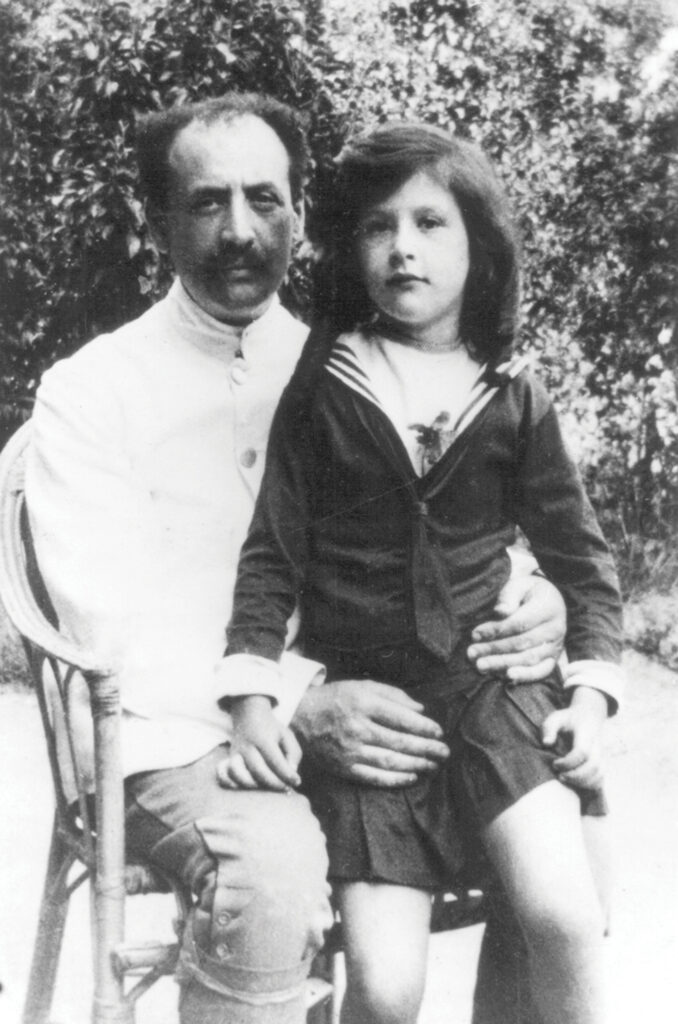

The Weils were a respectable bourgeois family—Bernard was a prosperous doctor, Selma an anxiously protective mother—but they seem to have carried out such orders without demur. Perhaps they saw them as not much different from Simone’s periodic requests to be sent coffee filters or a swimsuit, which she could presumably have found a way to buy herself. After all, Weil was a genius—when she took the entrance examination for the École Normale Supérieure in 1928, she received the highest marks in philosophy in the entire country—and had the genius’s traditional privilege of practical incompetence.

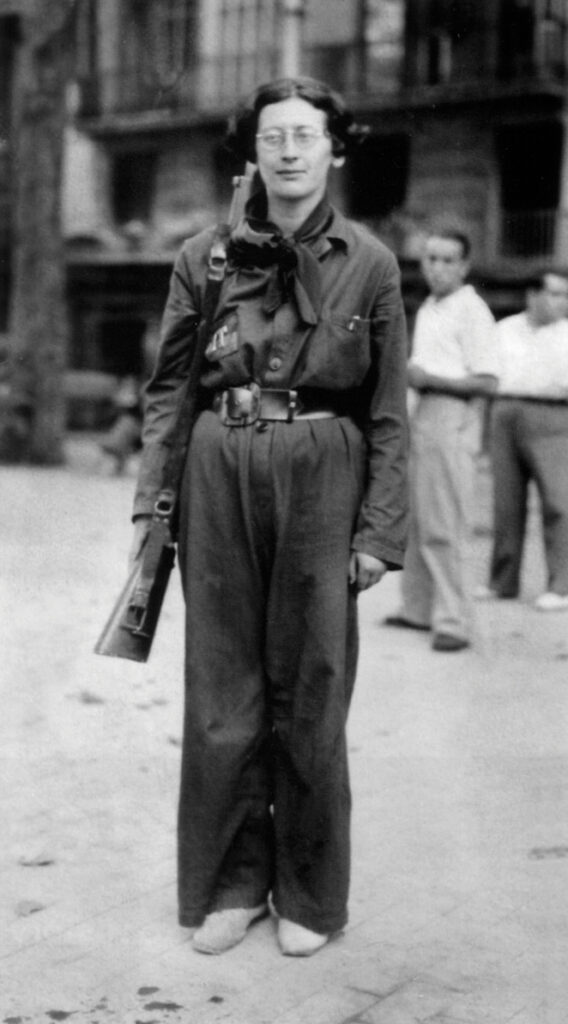

When Weil volunteered to serve with a frontline anarchist brigade in the Spanish Civil War, she was seriously injured—not in combat, but by stepping into a vat of hot cooking oil. Bernard and Selma were already waiting at the Franco-Spanish border to take her home; they had moved to Perpignan to be as close as they could get to their incomprehensible daughter, who kept sending reassuring notes: “It’s interesting, and there is absolutely no danger. . . . Everything is going really well. . . . Don’t be worried, all right?” When Weil visited Germany in 1932, six months before the Nazis took over, she was equally sunny: “Honestly, I feel completely safe, and that would be true even if Hitler were to take power.”

Such expressions of loving concern make Weil’s letters home often quietly moving, even when the substance is businesslike. But it is clear that her love for her parents went along with an iron refusal to admit them to her inner life. Perhaps the risk of being smothered was too great. “I had a funny dream this morning,” Weil wrote her mother in spring 1934. “I dreamed that you said to me: I love you too much, I can’t love anyone else anymore—And it was dreadfully painful.” It is the only time in the correspondence Weil appears so emotionally unguarded, but a few lines later she is back to issuing orders: “You should (1) invite Schwartz—(2) ask him if he sees de Monzie . . . (3) casually talk to him about Boris, and sing his praises.”

The experience Weil kept most completely hidden was her religious journey. Happy to tell her parents about her participation in labor strikes and political demonstrations, she turned secretive once Christianity began to engross her life in the late 1930s. In June 1937, Weil was on a tour of Italy when she visited a small chapel associated with St. Francis of Assisi. “You really came close to losing me forever,” she writes jokingly to her parents, suggesting that the place was “so pleasant, so serene” that she wished she could stay there. Five years later, Weil wrote to Father Joseph-Marie Perrin, a Catholic priest with whom she discussed conversion, that this chapel was the site of her first Christian mystical experience: “Where Saint Francis often used to pray, something stronger than I was compelled me for the first time in my life to go down on my knees.”

Weil kept this experience from her parents just as she concealed the reality of combat in Spain and her mortal illness in London, and for the same reason: She knew it would hurt them. But why, exactly? Not because Bernard and Selma Weil were believing or observant Jews, though they had been raised in traditional households. “I do not know the definition of the word, ‘Jew’; that subject was not included in my education,” Weil wrote in 1940. “The Hebraic tradition is alien to me.”

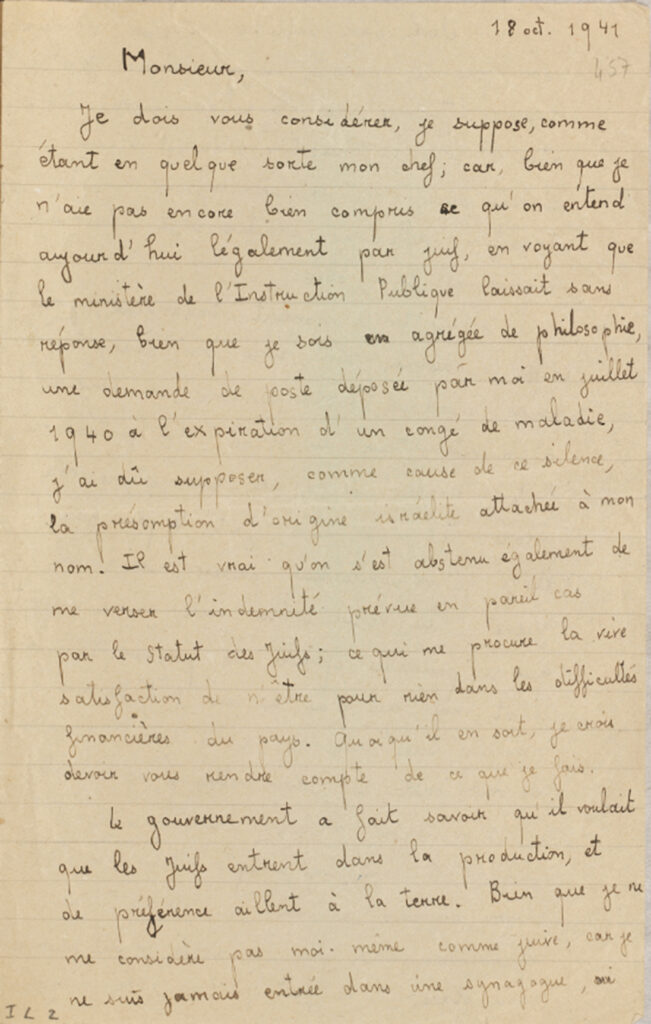

She could have been speaking for many European Jewish intellectuals of her generation. What makes Weil’s disavowal uniquely troubling is that she made it in a letter to the minister of education of Vichy France, complaining that she had been forbidden to teach under the Nazi puppet state’s anti-Jewish laws. Rather than complaining that the anti-Jewish law was unjust (which she also certainly believed), she argued that it should not apply to her because she was not really a Jew.

Perhaps it is this rejection of solidarity that Simone Weil wanted to conceal from her parents, more than her Christian beliefs. After all, this is the sin of the wicked son in the Haggadah, who responds to the Seder by asking: “What is this worship to you?” In saying “to you” and not “to him,” the Haggadah explains, he separates himself from the community, thus denying “the very core of our beliefs.” Indeed, in the modern Jewish world, lack of religious faith has become far less objectionable than lack of communal loyalty.

Weil’s rejection of solidarity, at the moment of maximum danger for the Jewish people, is responsible for the markedly different reception of her work among Jews and Christians—a gulf that is perhaps wider in her case than with any other twentieth-century thinker, even a professed Nazi like Martin Heidegger. When Weil’s books began to appear in the late 1940s, several years after her death, her exigent, paradoxical understanding of Christian faith struck a deep chord among Christian intellectuals. In his introduction to the first English edition of her magnum opus, The Need for Roots, T. S. Eliot wrote that “Simone Weil was one who might have become a saint.” Czesław Miłosz, who translated her work into Polish, wrote that “she has instilled a new leaven into the life of believers.”

Ironically, part of Weil’s authority as a Christian thinker came from her refusal to be baptized. While she embraced Catholicism in principle, she would not enter the Catholic Church, in part because she rejected the association of faith with institutional power. Waiting for God, a posthumous anthology of her writing published in 1950, includes a series of letters to Father Perrin in which she explains that she is called to remain at “the point where I have been since my birth, at the intersection of Christianity and everything that is not Christianity.” After the war, when the church had been tarnished by its accommodation with fascism and nationalism, Weil was able to speak for the faith all the more effectively because she remained outside it.

Less often acknowledged, though unmistakable, is the way Weil’s Jewishness made her a uniquely acceptable representative of Christianity after the Holocaust. Six million Jews had been murdered in Europe, often with the approval or connivance of Christian believers and institutions. Yet here was a Jew who, in the midst of the slaughter, affirmed the moral authority of Christianity. In May 1942, Weil wrote of the need for “a new saintliness,” which would expose “a large portion of truth and beauty hitherto concealed under a thick layer of dust,” and after her death she became just such a saint for many Christians.

Jews have tended to feel differently. In 2021, Robert Chenavier, one of the editors of A Life in Letters and the president of the Association for the Study of the Thought of Simone Weil, published a short book titled Simone Weil: Une Juive antisémite? In the book, which has not yet been translated into English, Chenavier takes issue with a number of Jewish writers—mostly unknown in the US, with the exception of George Steiner—who have argued that Weil was motivated by a pathological hatred of Jews and Judaism. Chenavier rebuts these critics by showing that they have often taken passages of her writing out of context and misinterpreted them, sometimes grossly.

For instance, in an essay on Weil, Steiner wrote that she made “approbatory comments” about Hitler, praising his “Roman grandeur,” because she believed “anything was preferable to the unctuous hypocrisies, corruptions, and facile materialism of bourgeois capitalist democracy.” Chenavier wonders if Steiner’s characterization of Weil is a case of “ignorance, bad reading, or a lack of intellectual honesty,” and indeed it is hard to imagine that anyone could read even a few pages of her work and come away with the impression that she considered “Roman greatness” a compliment.

At the heart of Weil’s political thought is a historical fable in which ancient Greece represents the best of humanity and Rome the worst. “The Romans really were an atheistic and idolatrous people; not idolatrous with regard to images made of stone or bronze, but idolatrous with regard to themselves,” she writes in The Need for Roots. “It is this idolatry of self which they have bequeathed to us in the form of patriotism.” When Weil looked at Nazi Germany, she saw imperial Rome, and vice versa. Far from praising Hitler, calling him Roman was her supreme condemnation.

When it comes to explaining why Simone Weil inspires such hostility that her critics are led into inaccuracy and exaggeration, Chenavier is less convincing. Another of his targets is the French Jewish writer Paul Giniewski, who suggested that if Weil had lived to see the liberation of France, she ought to have been shot alongside fascist intellectual collaborators like Robert Brasillach. Of course, Weil was as far from being a collaborator as she was from admiring Hitler, and Chenavier scoffs at Giniewski’s assertion that Weil’s way of thinking about Judaism was no different from that of the “gurus of fascism.”

Yet although he correctly objects that Weil “did not call for murder of individuals or the extermination of a people,” there is no doubt that she harbored a ferocious hostility to Judaism. In the notebooks she kept from 1940 to 1942, while living as a refugee in Vichy France, Weil expanded her historical fable to include Israel, which she placed alongside Rome as the source of evil in Western civilization. When selections from these notebooks were published after her death in the book Gravity and Grace, alongside her insights into Christian self-abnegation there were observations like these, in the chapter titled “Israel”:

It is not astonishing that there should be so much evil in a civilization—ours—contaminated to the core, in its very inspiration, by this terrible lie. The curse of Israel rests on Christendom. Israel meant atrocities, the Inquisition, the extermination of heretics and infidels. Israel meant (and to a certain extent still does . . . ) capitalism. Israel means totalitarianism, especially with regard to its worst enemies.

In writing such things, Weil did not intend to contribute to the persecution of Jews. She was writing in the privacy of her notebook, and if she had lived, these lines might never have been published. That fact alone separates her from the antisemitic writers Giniewski compared her to. But the way Weil writes about Judaism, here and elsewhere, isn’t merely offensive. It is ignorant and thoughtless in ways that ought to pose a serious problem for her standing as a religious thinker.

Weil’s idea that ancient Israel, like ancient Rome, was a protototalitarian state and that the Jewish people worshiped a bloodthirsty God was based on her reading of the passages in the Torah calling for the extermination of the Canaanites. Of the rest of the Hebrew Bible, she had little to say, and of the ways Jews themselves have interpreted it over the last 2,500 years, she knew nothing at all; as she said, the subject was not included in her education. A product of France’s most elite educational institutions, Weil was steeped in an intellectual tradition that, in both its Christian and post-Christian forms, habitually used Judaism as a symbol for everything it hated in itself. For an assimilated Jew to resist that tradition, to think about Judaism from the inside, required a determination even rarer than genius.

Had Weil thought more deeply about the Hebrew Bible, she would not have been able to commit the moral and historical absurdity of conflating the Jewish idea of chosenness with Roman imperialism—as when she complained that France is “corrupted . . . by the dual Roman-Hebrew tradition, which all too often carries the day with us as against pure Christian inspiration.” In fact, the Jewish belief in a Promised Land is the opposite of the Roman ambition for unlimited expansion. What is novel and unique to Judaism isn’t the idea of claiming divine sanction for war; Egyptian and Babylonian kings had been doing that for thousands of years before Moses. Rather, it was that the Israelites’ claim on their (small, strictly delimited) territory came from a covenant with God, which meant living up to God’s ethical commandments. The distinctively Jewish idea is not conquest but exile—the belief that the Jewish people will forfeit their land if they do not continue to deserve it.

What is infuriating about Weil’s thought, from a Jewish perspective, is that all the values she exalts as distinctively Greek, Christian, and French, and castigates Judaism for lacking, can in fact be seen as emphatically Jewish. When Weil writes that Israel’s “God, even though immaterial, was a temporal sovereign on a par with the [Roman] Emperor,” she forgets that the first critique of temporal sovereignty ever made was Samuel’s, when he warned the Israelites not to ask for a king so that they could be “like all other nations.” Later, the prophets spoke for God against the kings of Israel and Judah, calling for the destruction of their own country in the name of justice. This much Weil could have seen simply by reading the Bible. If she had explored rabbinic literature, she would have discovered its profound mistrust of secular power: “Shemaiah used to say: love work, hate acting the superior, and do not attempt to draw near to the ruling authority.”

As for the central concept of Weil’s political thought—the importance of rootedness, enracinement, for human flourishing—it is Judaic through and through. In her last months, Weil was tasked by the Free French leadership with writing a memorandum on how to reconstruct France after the liberation. This assignment grew into The Need for Roots, which quickly leaves practicalities behind to become a philosophical meditation on what makes a good society.

While completing the book in July 1943, Weil wrote to her mother about her “growing inner certainty that there is a repository of pure gold in me that must be passed down. Except that experience and the observation of my contemporaries make me more and more convinced that there is no one to receive it.” Indeed, Weil’s text was of no use to the Free French authorities in their postwar planning; they must have been baffled by many of her suggestions, such as teaching French peasants about the dignity of labor by having them read Hesiod and “Piers Plowman.”

But when The Need for Roots was published in 1949, Weil’s vision of a patriotism based on compassion and humility, rather than national self-idolatry, struck a deep chord in postwar Europe. She argued that one should be attached to one’s people not because it is better than all the others, but because living in community is a spiritual necessity. “To be rooted is perhaps the most important and least recognized need of the human soul,” she writes:

A human being has roots by virtue of his real, active and natural participation in the life of a community which preserves in living shape certain particular treasures of the past and certain particular expectations for the future.

Weil argues that modern society tends to deprive human beings of community and history, creating “uprooted” people easily swayed by political ideology. “Totalitarianism’s idolatrous course can only be arrested by coming up against a genuinely spiritual way of life,” she writes. It follows that, for Weil, the key to postwar reconstruction was not more emphasis on democracy and human rights but a more genuine connection to history and community. “Loss of the past, whether it be collectively or individually, is the supreme human tragedy, and we have thrown ours away just like a child picking off the petals of a rose,” Weil concludes.

This image describes the attitude of assimilated Jews like the Weils toward Judaism so perfectly that Simone Weil’s refusal to acknowledge it feels almost Freudian. In Judaism, if anywhere, she could have found a belief system that places community and history at its core, that sees ritual as a tool of continuity, that clings to its specificity against enormous pressure. How many Jews in the modern world have felt about Judaism in exactly the way that Weil recommends to the French: “This poignantly tender feeling for some beautiful, precious, fragile and perishable object has a warmth about it which the sentiment of national grandeur altogether lacks.”

Far from acknowledging the congruity between what she needs and what Jewish tradition offers, however, Weil repeatedly blames Jews and Judaism for the “uprooting” of the modern world. The ancient Israelites, she writes in The Need for Roots, were not a people but “escaped slaves,” deracinated from the start, and she warns that “whoever is uprooted himself uproots others.” In Gravity and Grace, she makes the point more explicitly: “The Jews, that handful of uprooted people, have caused the uprootedness of the whole terrestrial globe.”

At such moments, Giniewski’s charge that Weil’s understanding of Judaism overlaps with Nazism’s starts to sound less irrational. The idea that rootless Jews acted as corrosive agents in European society was at the core of modern political antisemitism. Weil would have heard such language all her life from French antisemites; now she was endorsing these ideas, at the very moment when they had blossomed into mass murder.

In this context, Weil’s praise of rootedness can be seen as a way of exempting herself from the charge of deracination. By attacking Judaism in the same terms used by the French right since the Dreyfus Affair, she confirmed that her place was among the rooted French Catholics, not the rootless Jews. It was all the more necessary to insist on this point because, in fact, Weil belonged to the first generation of her family to be born in France. Her mother, who was born in Rostov and moved to Belgium before settling in Paris, had much in common with the Eastern European Jewish refugees whom the Vichy government was deporting to Auschwitz at the very moment Weil was writing The Need for Roots. Indeed, that is why she agreed to leave France with her parents in 1942; it was as Jews, not as French citizens, that they were in mortal danger.

But in subsequent letters to her brother, Weil bitterly upbraided herself for leaving. “I am more and more cruelly torn day after day by regret and remorse for having been weak enough to follow your advice a year ago,” she wrote in April 1943. Her insistence on returning from America to London was self-imposed penitence, but it wasn’t enough. Her goal in joining the Free French was to sell them on a plan to parachute herself and other female volunteers into occupied France to serve as nurses. The fact that she would almost certainly be captured or killed was not a drawback, from Weil’s point of view, but the chief selling point.

In a letter to André, written in September 1941 while she was still living in Vichy France, she remarks that the idea was inspired by “certain passages of Tacitus on the combat methods of the barbarian and semi-nomadic peoples of the 1st century.” The editor’s note explains that Tacitus wrote that the ancient Germanic tribes, when going into combat, put a young girl in the front line to inspire the warriors’ morale. In other words, Weil wanted to die to inspire the French resistance.

When this proposal was rejected as useless and suicidal, Weil refused to eat any more than the official rations prescribed in occupied France. In fact, she had always disliked food and had to be coaxed to eat; Weil’s biographer Francine du Plessix Gray suggests she would now be called anorexic. This radical deprivation made it impossible for her to fight off the pneumonia infection that killed her. On her death certificate, a British doctor gave the cause of death as suicide: “The deceased did kill and slay herself by refusing to eat whilst the balance of her mind was disturbed.”

Weil’s rationale for self-starvation was based on an error. The official rations in occupied France were too low to sustain health, but the country did not see widespread starvation, because almost everyone got their food supplies on the black market. The only places in France where people did die of malnutrition were in jails and mental asylums, because those were the only places where rationing was strictly enforced. Weil probably knew as much, but she was determined to die for France and chose this way to justify it.

Starvation served another purpose as well. Simone Weil left France in July 1942; four months later, Nazi Germany did away with the Vichy regime and occupied the southern part of the country. Had Weil stayed behind, she would almost certainly have died in a gas chamber. But that would have meant dying as a Jew, along with millions of other victims of the Holocaust. By escaping and then starving herself to death, Weil ensured that her death would be what she wished her life had been: simply and exclusively French.

Suggested Reading

Drawing Conclusions: Joann Sfar and the Jews of France

The great French comic artist is now working at the height of his considerable powers, and he is obsessed with questions of Jewish identity and life in Europe.

“I Am Impossible”: An Exchange Between Jacob Taubes and Arthur A. Cohen

In the summer of 1977, two old friends ran into each other in front of a Paris bookstore and found themselves arguing about Simone Weil, Judaism, and their lives.

Pancho Villa and the Star of David Men

When the Young Men's Christian Association began offering wholesome recreation to soldiers in 1916, Jewish leaders were as as worried about evangelism as they were about bars and bordellos.

Spy vs. Spy

Beginning in 1940 the French and the Zionists had a common enemy—the British.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In