The Witness

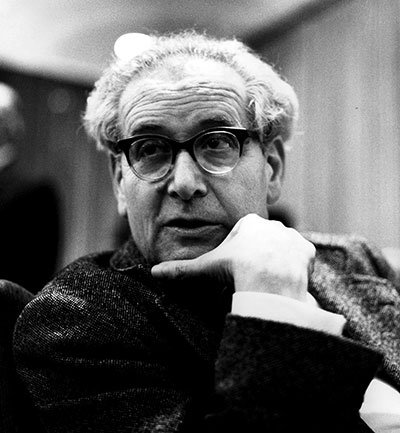

On July 3, 1943, a 33-year-old inmate of Theresienstadt gave a talk about Franz Kafka. Decades later, invited to write a “living obituary,” he would introduce himself thus: “H. G. Adler was born in 1910 in Prague in the last years of the Habsburg Empire as Franz Kafka began to forge his unique art.”

Raised in an assimilated German-speaking family and baptized as a Protestant at age 12 (he later called the conversion a “charade”), Adler had seemed destined for a stellar literary career as an heir to the Prague Circle, a group of German-language writers that included Kafka, Max Brod, and the philosopher Hugo Bergmann. As Adler’s longtime friend and rival Elias Canetti remarked in 1937: “Even in Germany it would have been hard to find a man more dominated by German literary tradition.”

Unlike Brod and Bergmann, Adler did not make it to Palestine. “Although I could see what was happening,” he recalled, “for some strange reason I didn’t leave, even though I made some attempts to do so in 1938 and 1939.” Trapped in Nazi-occupied Prague, Adler had been assigned in late 1941 to “shattering” work in the city’s Jewish book depository, which in his description “soon turned into a center for the liquidation of possessions stolen from Jewish apartments.” While he was there, “Kafka’s library (taken from his sister’s apartment) passed through my hands.”

On that summer Saturday afternoon in the Theresienstadt barracks, on what would have been Kafka’s sixtieth birthday, Adler spoke of his literary predecessor with somber nobility as a “symbol of the suffering human of these times for whom no way out exists.” At the conclusion of the lecture, Kafka’s youngest sister, Ottla, thanked him on behalf of her family. Three months later, she was deported to Auschwitz, never to return.

Within weeks of his arrival in Theresienstadt, Adler commanded himself: “You must observe life in this society as soberly and objectively as a scientist studying an obscure tribe.” Adler did not expect to survive. If he did, however, he resolved to encompass the experience of the camps “in two different ways. I will research it in a scholarly manner and so separate it from myself completely, and I will also describe it in a poetic manner.”

Theresienstadt, the so-called model camp—previously a prison and then a garrison for the Czech army—featured its own pseudopostage and currency, but no gas chambers: It served instead as a depot for transports to the east. Adler called it a Totenmühle, or death-mill. The SS deported some 88,000 people from Theresienstadt; of these, 3,500 survived. An additional 35,088 perished in the unbearably cramped confines of the camp itself. “For the few who managed to live through it,” Adler wrote, “Theresienstadt held a grip on their lives forever. . . . It was the most hellish ritual mask that death ever wore.”

In October 1944, after 32 months in what he called a “bottomless abyss of coercion,” Adler and his wife Gertrud, head of Theresienstadt’s medical lab, were crammed onto a freight car and deported to Auschwitz along with her 64-year-old mother. The mother and daughter were gassed on arrival.

Adler survived not only Auschwitz but also Langenstein, an underground forced-labor subcamp of Buchenwald. Describing the latter, he wrote:

Just imagine, you are yourself half-starved, crawling with lice and filthy, tired and feeling faint, and all around you can be heard the cries of the most pathetic misery as each day masses of people die over whose bodies you trip, as you notice how they have been literally beaten and also desecrated, as well as robbed, and how they have been forced to do deadly work that even a healthy and well-fed person could not stand to do, while you have to look on and can do nothing at all.

Adler was liberated by American soldiers in April 1945; although he had never considered himself much of a Prague patriot, he returned to his native city in June. Eighteen members of his family had been murdered, including his mother and father. “Neither Dante nor Dostoevsky,” he noted the next month, “could have dreamed up such an unreal Hell, though Kafka could, for he has become a prophet, a realistic prophet of these horrors.”

Before his deportation from Theresienstadt, Adler had handed Rabbi Leo Baeck a black leather briefcase for safe keeping. Besides a hundred poems he wrote in the camp, the first draft of a novel, and notes for his lectures, it held papers Adler and Gertrud had collected on the camp. “Many people stole bread, I stole documents!” he said.

After liberation, Adler returned to Theresienstadt to retrieve the briefcase. Determined to bear witness to the destruction and desecration, he began almost compulsively to transform its contents into a book. “I felt that I couldn’t go on,” he said, “that the pain of what had happened would leave within me an abyss of despair, a gaping emptiness, if I didn’t try, in this way, to overcome the monstrosity both intellectually and emotionally; and so I had no other option but to begin my research.”

In a single 10-page serpentine sentence at the climax of W. G. Sebald’s final novel, Austerlitz, the title character burrows through a “heavy tome, running to almost eight hundred close-printed pages, which H. G. Adler, a name previously unknown to me, had written between 1945 and 1947 in the most difficult of circumstances, partly in Prague and partly in London, on the subject of the setting up, development, and internal organization of the Theresienstadt ghetto.” Jacques Austerlitz, a Czech Jew who lost his mother to the Theresienstadt death-mill, reads the book “down to the last footnote,” afterwards lamenting “that now it is too late for me to seek out Adler.”

In 1947, before the imminent Communist takeover that would once again rob Czechoslovakia of its independence, Adler fled from Prague to England. “I celebrate as my day of liberation that of my arrival in England,” he said, “rather than the day in April 1945 on which I was rescued from the power of Nazi Germany.” He was met on arrival by Elias Canetti; the anthropologist Franz Baermann Steiner, his closest friend; and Bettina Gross, a Prague-born artist soon to become his second wife.

Adler carried with him the bulky first draft of what would become one of the first scholarly studies of the Holocaust: his comprehensive study of Theresienstadt. Completed the next year, its understated but tactile prose offered a detailed anatomy of every aspect of the camp: the adulterated “wordscape” of the German camp jargon; the daily caloric intake for malnourished children; the varieties of work details; the cynical charade that duped inspectors from the International Red Cross during their visit in June 1944; and the psychology of Judenrat elders such as Benjamin Murmelstein, whom Adler describes as “well armed against compassion” (and who sued the publisher for damages). In the only personal words in the volume, Adler dedicated it to Gertrud, who “for thirty-two months did all she could for her family, up to the limits of her strength.”

Adler’s friend, the Vienna-born novelist Hermann Broch, praised the book’s “cool and precise method” and “the vivid immediacy of the writing.” Even burdened by bureaucratic detail, the narrative collage reads like a novel. In fact, Adler described his book as “a Kafka novel with the terms reversed, transcribed according to reality.” His only son, Jeremy Adler, professor emeritus of German at King’s College London, told me in a telephone conversation: “The world of Terezín struck him throughout as Kafkaesque.”

The book struck many readers as miraculous. “It’s hard to imagine that such a gentle and sensible person remained so mindfully present and capable of objectivity amid such an organized Hell,” Theodor W. Adorno wrote, “. . . and for this he deserves not only the thanks of those on whose behalf he wrote, but the undiminished admiration of all the rest of us who believe that they could never equal him.”

And yet only in 1955—and only with Adorno’s intervention in raising funds to cover printing costs—did Adler succeed in publishing the book in Germany, where it has remained a fixed point of reference ever since. In the meantime, failing to secure an academic post, Adler lived in penury. (He succeeded in getting full reparations from Germany only in 1960.)

Attempting to find an American publisher, Hermann Broch enlisted the help of Hannah Arendt of Schocken Books and Elliot Cohen, founding editor of Commentary magazine—to no avail. It would be 62 years before Theresienstadt 1941–1945: The Face of a Coerced Community would appear in Belinda Cooper’s faithful and fluent rendering into English (edited by Amy Lowenhaar Blauweiss). “[I]t seems inconceivable today how difficult a task it was,” Jeremy Adler noted, “how little moral support he received—there was no question of financial aid!—and how much opposition he encountered. . . . [T]he scholarly establishment proved at best indifferent and at worst hostile.”

That Adler—author of 26 books of history, fiction, poetry (his volume of collected poems runs to 980 pages), and what he called “experimental theology”—has remained so unknown to English readers for so long is a dereliction. Peter Demetz, the Czech-born scholar of German at Yale, called it “one of the great intellectual scandals of our time,” given that Adler rightfully belongs “on the very heights of world literature.”

In H. G. Adler: A Life in Many Worlds, a fascinating and scrupulously researched authorized biography of Adler, Peter Filkins, a professor at Bard College at Simon’s Rock, cites “the critical neglect that hung like a veil over his achievement,” especially his six novels. “Neither Germany nor the world was ready for novels about the Holocaust in the 1950s,” Filkins writes elsewhere. At the same time, drawing on Adler’s extensive literary estate kept at the German Literature Archive in Marbach, Germany (Oxford’s Bodleian wasn’t interested), Filkins unveils the lambent artistry of that achievement.

Other survivors wrote memoirs. According to Filkins, however, Adler was “the first Jew writing in German to publish a novel about his ordeal [in the camps].” A trilogy of his novels has in the last decade belatedly come out in Filkins’s finely wrought English translations.

Panorama, a first novel “soaked in autobiography,” as Adler put it, was written in 1948, but it took 20 years to find a publisher courageous enough to bring it out. In 10 vignettes, its gradually coagulating language tells Josef Kramer’s coming-of-age story in Bohemia, affording us glimpses of him as a suffocated boarding-school student (he calls the school “The Box”), a 20-something staffer at a Prague cultural center mired in Marx Brothers absurdity, a forced laborer imprisoned in “a deep hole of horror” and “robbed of the justification for existence,” and an unmoored exile in Britain who retreats into philosophical ruminations. Adler no doubt intended his character’s name to evoke Josef K., Kafka’s most well-known protagonist.

The Journey, with its intentionally disorienting shifts of tense and voice, was written in 1950 and published by a small press in Bonn in 1962. Elias Canetti called it a “masterpiece.” Despite his aversion to Holocaust fiction, Harold Bloom would declare that “this book helps redeem an all-but-impossible genre.” Not everyone agreed. Rejecting the novel, an editor at the British publishing house Secker & Warburg advised Adler that “he would have more success if he wrote a book on the death camps in the style of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and The Dead.”

The Wall, a modernist meditation on survivor’s guilt, was completed in 1956, though not published in Germany until 1989, a year after Adler’s death. Its main character, Arthur Landau, is divided by an invisible wall of incomprehension from his past and present both. “I soon appreciated that there was one too many people in the world, and that was me.” In a poignant passage, Adler’s narrator compares Landau to a signpost,

scorned by disaster in a deadly snowstorm; when the storm had moved on, all his companions had been frozen to death, the signpost is shattered, no destinations can be deciphered on its fragments, and the paths themselves have ceased to exist.

Landau, unbowed, is given the first and last word: “You have to be able to feel broken and yet not damn the world.”

Timely and untimely, each of Adler’s novels inhabits the borderland of reverie and reality. They hardly mention the words “Nazis,” “Jews,” or “camps.” In The Journey, for example, Adler calls Jews “the forbidden,” and in Panorama “the lost ones.” He refers not to the gas chamber but to the Mordtempel (temple of murder); not to Hitler but to “the Conqueror.” He names Prague only as “over there.” “Adler’s mix of allusions to the past, present, and future,” Filkins observes, “taps the ability of montage to link seemingly disparate times and places such that, again as in Kafka, one place is interchangeable with another amid the nightmare of a seemingly inescapable labyrinth.”

Adler returned in his last decades to the documentary mode. Drawing on his extensive research in Gestapo files, he submitted a 41-page affidavit to the Israeli prosecutors in the trial of Adolf Eichmann. Awaiting trial, Eichmann read parts of Adler’s Theresienstadt study in his cell. Arendt relied on it heavily in her reporting on the trial in Eichmann in Jerusalem.

At a time when interest in such things was still scant, Adler meanwhile coedited a 400-page collection of documents and eyewitness accounts called Auschwitz: Testimonies and Reports (1962). Filkins calls it “the first major documentary account of Auschwitz in any language and the first time that experience of the victims was told from ‘the inside’ rather than only from the perspective of the perpetrators.”

Finally, Adler labored on The Administered Man, an encyclopedic account of the deportation of German Jews and of the administrative apparatus and abuse of state power that made it possible, which he published in German in 1974. Adler considered it his “greatest scholarly achievement.” It is still untranslated.

In assessing that achievement, Jeremy Adler remarked of his father: “The prisoner became an observer, the observer a theorist, the theorist a witness, and the witness an admonisher.” What binds those roles together, he added, was his father’s conviction, “ultimately grounded in his Jewish faith, that a system of beliefs, ethical values, and the basic political concepts of human rights and democracy do make sense. Their abuse, however terrible, did not destroy them.” In the first essay he wrote after the war, H. G. Adler expressed the hope “that something can be formed out of this last darkness that may indeed become light.” Contrary to his own lecture on Kafka, Adler embodied that hope: Even where the labyrinth’s signposts are shattered, a way out toward the light exists.

Suggested Reading

Jewish Destiny in a Cheek Swab

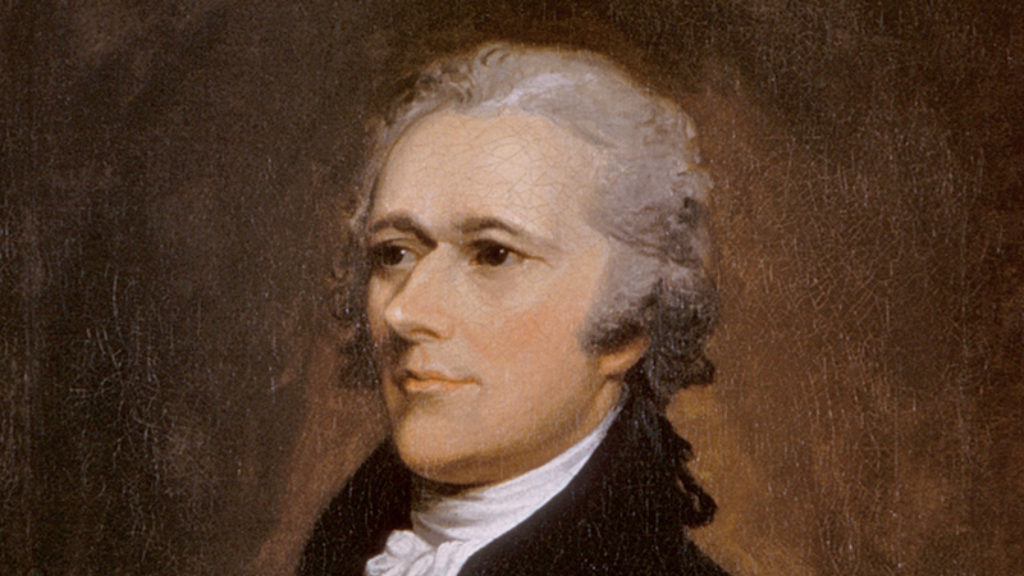

Possible Jewish ancestry has fascinated both Jews and non-Jews when it comes to American historical figures, reaching as far back as Alexander Hamilton.

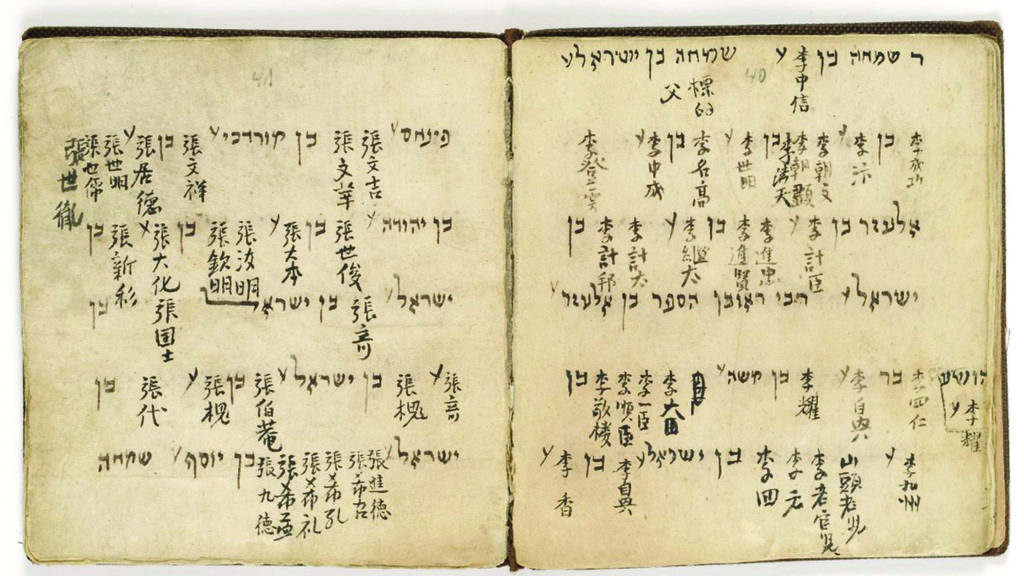

Why Is This Haggadah Different?

The Haggadah of China's Kaifeng Jews is not all that dissimilar from your Maxwell House version—but it speaks volumes about the community that produced it.

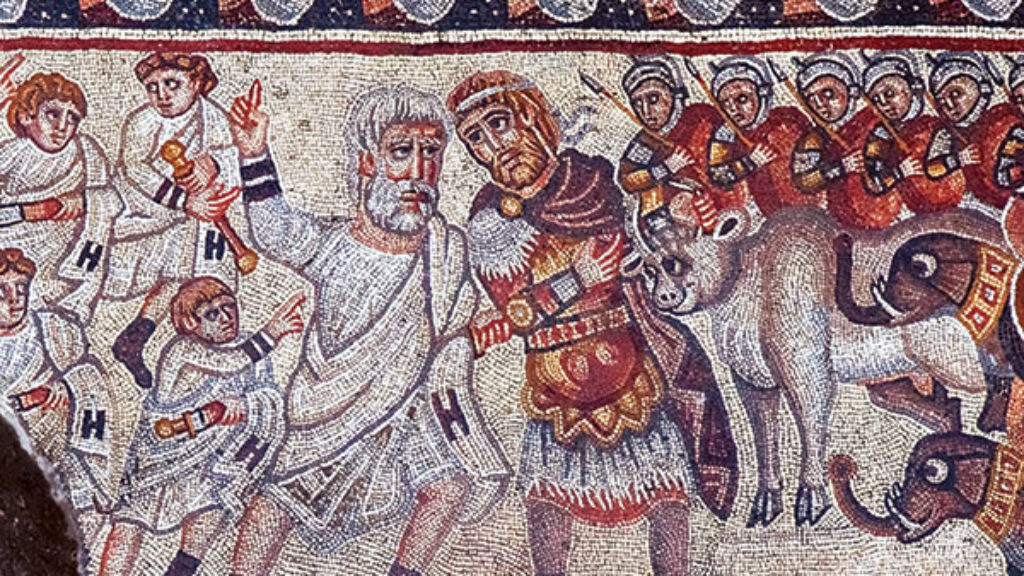

God’s Law in Human Hands

A Judean, a Stoic, a Jewish philosopher, a Jesus follower, and a rabbi walk into a seminar room at Yale, and Professor Christine Hayes asks them, “What do you mean when you say divine law?”

Common Clay

Virtually nothing of Babylonian Jewry of the talmudic period, from the 3rd to the 6th century C.E., has survived beyond the Babylonian Talmud itself to help contextualize or confirm the many things the text tells its readers.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In