Common Clay

What do we really know about the Jews who produced the Talmud and, along the way, formed Judaism as we know it today? Seemingly, everything, but maybe not very much at all. The Babylonian Talmud is a gargantuan work of nearly two million words that offers a panoramic view of classical Jewish life, law, and lore. In its distinctively terse but somehow freewheeling style it touches on everything from the intricacies of torts and theology to the charms of Mesopotamian cuisine and Persian plumbing. Yet virtually nothing of Babylonian Jewry of the talmudic period, from the 3rd to the 6th century C.E., has survived beyond the text itself to help contextualize or confirm the many things the Talmud tells its readers. There has not been a single Babylonian synagogue dug up by archaeologists (or at least none reported), and, notwithstanding some early rumors about the now infamous cache of Jewish books confiscated by Saddam Hussein that turned up in the Second Iraq War, there are virtually no ancient Jewish relics from Babylonia to speak of. Scholars of this crucial period of Jewish history can feel trapped in a vicious hermeneutic circle of trying to write the history of the Talmud and its rabbis by closely scrutinizing the words of the rabbis in the Talmud.

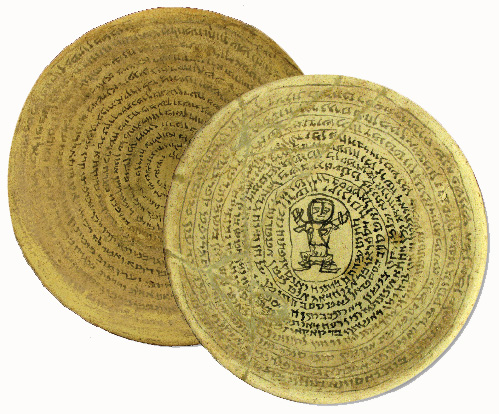

Actually, for over a century historians have had at their disposal one sizable cache of Babylonian Jewish artifacts: over a thousand magic incantation bowls. They were essentially amulets for people seeking health, wealth, and other ordinary objects of human desire, whose magical spells were inscribed, oddly enough, on everyday kitchenware. The typical incantation bowl is earthenware and about the size of a cereal bowl. The magical writing is etched on the inside and spirals from the middle out, though not infrequently the center of the bowl also contains an image. Despite the apparent limitations of the genre, the magic bowls contain a rich treasure trove of Babylonian Jewish culture, including the names of the people who commissioned them, playful etchings of demons shown bound and begging, highly imaginative folktales of seduction and divorce, and a snapshot of the Aramaic dialects spoken by the Jews and their neighbors during late antiquity.

For many years the incantation bowls were the private fiefdom of a small group of specialists—including James Nathan Ford, Dan Levene, Matthew Morgenstern, Christa Müller-Kessler, Shaul Shaked, and others—who sacrificed good years and good eyesight to deciphering them. Their efforts have yielded a substantial uptick in the publication of these artifacts, with the recently released and lusciously illustrated Aramaic Bowl Spells: Jewish Babylonian Aramaic Bowls, the first of a projected nine-volume edition of the 654 bowls in the famous Schøyen Collection, the largest private collection of manuscripts and related antiquities in the world, assembled by Oslo businessman Martin Schøyen.

One might have expected the bowls to have been immediately recognized as a treasured source for writing the history of talmudic Babylonia. Yet they have apparently been deemed by talmudists to be too superstitious, too folksy, or just too un-talmudic (the Babylonian Talmud itself never explicitly describes the bowls, though it does discuss amulets). Remarkably, the first profound appreciation of the bowls as objects useful for conjuring up the lost world of Babylonian Jewry can be found in the domestic confines of a popular novel.

The story of the incantation bowls’ discovery begins as a tale of mild colonialist curiosity that quickly melts into snooty scholarly dismissal. The first finds came in the mid-19th century, when an antiquarian, “ancient Babylonian fever” was sweeping across Europe. Fittingly, an early report of the bowls is tucked deep within Sir Austen Henry Layard’s Discoveries among the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, an 1853 best-seller adorned with a gorgeous frontispiece depicting Sennacherib’s magnificent palace. For someone like Layard, who uncovered the famous cuneiform library of Ashurbanipal and regularly sent priceless objects back to London that would form the core of the British Museum, the incantation bowls were little more than archeological flotsam—late artifacts good for a nicely appointed cabinet of curiosities, perhaps. It took more than half a century to see the first scientific edition of incantation bowls published, and by then most orientalists could hardly be bothered. J. P. Morgan had already invested a considerable fortune in purchasing ancient cuneiform tablets for scholars to study, and, as opposed to the hopeless superstitions found in the incantation bowls, the tablets documented the impressive statecraft and science of a far more ancient—but seemingly more advanced—Mesopotamian society than the Sassanid Empire.

And yet what the spell bowls lack in relative antiquity and apparent sophistication, they more than make up for in quotidian charm. The people who commissioned them sought relief from the slings and arrows of ordinary fortune, hoping that powerful spells might keep the pain and fear at bay. Take Mahdukh, daughter of Newandukh, a woman whose name appears throughout Aramaic Bowl Spells and who is often depicted in the incantations at the threshold of her home alongside her husband Gundasp. The poor woman seems to have suffered from terrible migraines. She experienced searing pain “in her head, in the ear, in the temple, and the eye-sockets” due mainly to the nefarious activities of a demoness named Agag. The goblins of these bowls are not stock figures, but richly drawn characters with extended families, favorite haunts, and identifying characteristics. For her part, Agag enjoys reclining “among the graves and among the roof-tops” (perhaps relating her name with the similar-sounding Semitic word for roof), her lineage is traced back six generations, and she has nicknames like “blinder,” “smiter,” “sightless,” “lame,” and “itchy.” Some bowls are adorned with etchings of demons that could have waddled off the drawing pad of the late Shel Silverstein. Their menace seems a put on, like Smurfs who went over to the dark side.

Their domestic modesty and cartoonish flourishes aside, the bowls are in fact carefully wrought pieces of metaphysical technology. Many of the bowls are written in a professional scribal hand, and they employ precise, technical formulas to magically bind demonic forces and prevent them from inflicting harm. While some bowls indeed contain the senseless sequences that sorcery is infamous for, others achieve a distinctive, almost poetic style. Biblical verses and Jewish prayers are freely invoked, stories that channel the power of talmudic sages like Rabbi Hanina ben Dosa and R. Yehoshua ben Perachia are told (a number of the texts in Aramaic Bowl Spells concern these rabbis), and passages are included that detail halakhically conceived divorces with the threatening unseen demons. Talmudic historians may prefer to think of the bowls as merely reflecting the popular culture of the unlearned hoi polloi, but the picture of Jewish life glimpsed in Aramaic Bowl Spells upends assumed divisions between elite and folk, common and learned, and scholarship and magic.

Purveyors of contemporary culture, on the other hand, have found in the bowls a story too rich and fabulous to ignore. In 2010, American artist Jewlia Eisenberg and her band Charming Hostess produced “The Bowls Project”—a dome-shaped art installation at San Francisco’s Yerba Buena Center for the Arts and an accompanying experimental rock album that set some real bowl incantations to an original score. In 2013, Israeli author Dorit Kedar published Komish Bat Mahlafta: A False Biography of a Real Woman, a novel inspired by the magic bowls. And Maggie Anton, the best-selling author of Rashi’s Daughters, has now published the second volume of a projected trilogy entitled Rav Hisda’s Daughter, which tells the story of a woman in a rabbinic family who takes up an apprenticeship in magic bowl production and goes on to an illustrious career as a sorceress. Correction: Maggie Anton’s Rav Hisda’s Daughter is a two-book series, not a trilogy. The Jewish Review of Books regrets the error.

Rav Hisda’s Daughter opens with the intimate voice of its protagonist:

I have always been blessed with a good memory. This gift from Elohim, which has allowed me to memorize the entire Torah and Mishna, as well as a myriad of incantations and spells, has also given me knowledge of the unseen world . . . But a good memory may also be a curse. I will always carry the burden of seeing the beloved husband of my youth stolen away by the Angel of Death before we’d been married five years. And the agony of losing a cherished child at the tender age of four, a budding blossom never to bear fruit.

Like legal documents, the chapters of Rav Hisda’s Daughter have subtitles that announce the years of the regnant Sasanian Iranian monarch, and there are echoes in the story of the massive wars fought between Rome and Persia during that time. Anton paints a fairly accurate picture of the lightning-fast dialectical give-and-take of the rabbinic study hall, and the sights, sounds, and smells of Babylonian Jewish life in late antiquity.

In the first volume we learn a good deal about the making of Mesopotamian beer, and we see how magic bowls were produced, from writing to home installation. Here is how Anton describes the dramatic preparation before a bowl placement ceremony:

We went inside, where Giloi showed me the lying-in chamber. The slaves, who’d accompanied Rahel on countless installations, set to digging the appropriate holes. As each pit was finished, I turned the corresponding bowl upside down, laid it at the bottom, and covered it with dirt, all while trying to keep my hands from shaking. After the final hole was filled, one slave held out the white linen robe for me to wear and the other helped me with the veil. As I’d seen Rahel do before, I stood tall and lifted my arms to the heavens. My eyes closed, I prayed for fortitude, and also that the Merciful One would hear and grant my request. I could feel my skin tingling, and when I looked down, the slaves were huddled at my feet and I knew the time had come.

While this scene is undoubtedly dramatic, most of the real action of the narrative takes place in the fluttering heart of the main character, Hisdadukh.

Hisdadukh’s name is an exotic-sounding Aramaic-Persian amalgam that simply means “Hisda’s daughter,” the Talmud’s colorless designation for the daughter of the prominent early 4th-century sage, Rav Hisda. Like A. M. Bauld’s Mozart’s Sister and indeed Anton’s Rashi’s Daughters trilogy, this a project that takes its cue from Virginia Woolf’s famous daydream: “Let me imagine, since facts are so hard to come by, what would have happened had Shakespeare had a wonderfully gifted sister, called Judith, let us say . . .” As daydreams go, this one is meticulously researched. Anton has quite remarkably pieced together an entire life from stray talmudic dicta, which, as she cleverly notes in an afterword, were never intended to directly reflect historical truth: “The Talmud is clearly not an historical text; some might go so far as to call it historical fiction.” In Rav Hisda’s Daughter, Anton has produced a historical synthesis that few talmudists could hope to achieve—were they even tempted to do so.

Hisdadukh is who she is, at least initially, by virtue of the men in her life. She is born into one of the Talmud’s most important rabbinic families and ends up marrying not one but two towering sages: When (in an anecdote Anton takes from tractate Bava Batra) her father asks which of his prize students she wants to marry, she replies “both.” Rava, the quicker of the two, says “I’m last” and indeed, Hisdadukh’s first husband, Rami, dies tragically young. And yet she is her own woman, insatiably curious and fiercely independent. She is an active and successful—if unofficial—participant in the home-based yeshiva her father heads. But Hisdadukh ultimately finds her calling beyond the study-hall when she begins to study magic bowl making under her sister-in-law and discovers among other magic “specialists” a vibrant, if competitive, female fellowship.

It is notable that aside from bringing the bowls out of the shadows of antiquity into pop culture’s neon glow, Eisenberg, Kedar, and Anton all share an assumption that the incantation bowls were largely produced by women. The authors of Aramaic Bowl Spells are fairly certain that this is incorrect, but I’m not sure how much it matters. In part, it reflects the ancient idea that magic appears on society’s margins, where women, too, are often confined. This prejudice has been taken variously. Instead of asking the patriarchy to embrace women and their sorcery, Eisenberg and Kedar celebrate women’s outsider status and revel in the bowl’s subversive, occasionally erotic charms. They thus participate in an established Jewish feminist discourse that reclaims peripheral and “dangerous” female figures and unleashes them on (or domesticates them for) an unsuspecting Jewish public, the most prominent example being the re-appropriation of the medieval legends of Adam’s dangerous first wife, Lilith.

Anton’s books, which are published by an imprint of Penguin and designed for Jewish-American book clubs, are a different story. She colors within the lines even if the hues are at times provocative:

As I wrote one incantation and then another, my mind whirled with the import of what I was doing . . . These vessels weren’t regular soup or serving bowls, they were kasa d’charasha, enchanted bowls, which means Rahel was an enchantress, a chareshata, maybe even a kashafa. But how could that be? . . . Rahel couldn’t be a kashafa. Kashafot were wicked.

By imagining the female relatives of prominent talmudic sages publicly producing magic bowls and other sorceries, Anton locates the magical arts at the very center of classical Jewish life. Unlike historical romances in which sex is breathlessly subversive and sorcery shocks, Anton keeps her sex scenes light and playful and marries traditional rabbinic piety with ancient sorcery. This is what makes Rav Hisda’s Daughter so surprising and, one might argue, so compelling. The relentlessly undramatic nature of the series is its genius.

The resurfacing of the magic bowls in contemporary popular culture is a phenomenon worthy of note, not just for book-of-the-month clubs and avant-garde artists. Scholars ought to take heed. Anton is onto something. Rav Hisda’s Daughter raises fascinating questions about what talmudists mean when speaking of “elite” in rabbinic culture, how rabbinic homes functioned simultaneously as both yeshivot and boisterous family estates, and how women and men actually interacted in these close spaces.

Set alongside the scholarship of Aramaic Bowl Spells, Anton’s forthrightly middlebrow novel proves to be an unexpected invitation to think about these questions. Most surprisingly, it suggests a way of re-conceiving the relationship between the Talmud and the magic bowls, and the lost Babylonian world that gave birth to Judaism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Moses and Hellenism

In a provocative new work recently published in German, Bernd Witte proposes nothing less than an “alternative history of German culture,” as the subtitle of his finely wrought work of scholarship tells us. Moses and Homer: Greeks, Jews, Germans is a historical and cultural argument animated by powerful indignation. This history, he insists, has yet to be fully confronted.

Appelfeld in Bloom

Israeli author Aharon Applefeld sifts through memories to understand the traumas of his past.

“Where They Have Burned Books, They Will End Up Burning People”

The surprising source for Heine’s prophetic remark that “where they have burned books, they will end up burning people” is a play about the fate of Muslims in Christian Spain.

Prague Summer: The Altneuschul, Pan Am, and Herbert Marcuse

A mysterious memoir of planes, Marx, and minyans.

Maggie Anton

What a fantastic review! I did find one error, however. "Rav Hisda's Daughter" is NOT a trilogy. The series is complete with "Apprentice" [book 1] and "Enchantress" [book 2]. So readers don't have to wait for a concluding volume.