History of Mel Brooks: Both Parts

In the 1940s, when Mel Brooks launched himself into comedy, he invented a persona: “Crazy Mel.” Perhaps you remember Crazy Mel: He was exuberant, reckless, loud—a wild, comedic id. Carson loved him. So did his audience. When Crazy Mel wasn’t vamping on TV, he was mugging in photos, including one gloriously zany shot in which he appears wild-eyed and open-mouthed, like a zoo animal hit with a tranquilizer dart. Silently, he conveys shock, fear, and aggression. “Tragedy is when I cut my finger,” Brooks once said. “Comedy is when you fall into an open sewer and die.”

That crazy photo appears, fittingly, on the cover of Funny Man, a rich and revealing biography of Brooks by Patrick McGilligan. It’s an ancient human truth that comedians get away with murder, and here’s proof, 640 pages of it. Consider Brooks’s films, which serve up whatever comic mischief your inner teenager craves. For schlock, Spaceballs. For sheer chutzpah, The Producers. For cheeky homage, Young Frankenstein, High Anxiety, and Silent Movie. For inspired, juvenile hokum—well, pretty much all of them.

If you love Brooks’s comic anarchy, you might hope for an appreciative biography. But McGilligan, a seasoned chronicler of Hollywood lives, is a cool, methodical narrator with a well-hidden ruthless streak. In Brooks, he has a fine subject, a well-known but not terribly well-understood creative genius. Brooks’s exuberance is legendary; his colossal egotism can be inferred—you don’t conquer Hollywood and Broadway without a healthy self-regard. But the rest of Brooks’s character may come as a harsh surprise. That he slavishly pursued wealth and fame, and was often selfish, spiteful, and cruel—Crazy Mel, minus the impish charm—is the main revelation here, served in huge, unsavory spoonfuls.

Funny Man tells the improbable story of how Melvin Kaminsky, the short, unbookish, unhandsome son of Kitty Kaminsky, became a comedy icon, an Emmy, Grammy, Tony, and Oscar winner. He was Kitty’s fourth son, supremely coddled and cared for. “I’d had such a happy childhood,” Brooks claimed, and maybe so, though its outlines were Dickensian. The Brooklyn Kaminskys were poor (“so poor, we do not even have a language—just a stupid accent!” wails a woman in History of the World: Part I). The family was grieving a tragedy—the death of Brooks’s father when Brooks was two. The main absence-presence in Brooks’s life, his father haunts this biography, as he apparently haunted Brooks long into adulthood.

Brooks’s school years were no easier, and McGilligan presents a far darker portrait than a previous biography, It’s Good to Be the King. School was misery—you had to sit still and be quiet—and stifled Melvin’s creative urges. He courted the jocks, becoming their jester and mascot. “Pretty soon, I came to hate them all,” he later recalled. “I really hated them for what they made me be.” Perhaps it was survival instinct. A small, sensitive child who wasn’t smart or athletic but sang “Toot, Toot, Tootsie” and “If You Knew Susie” with crack timing and crowd-pleasing gusto, he must have been a magnet for bullies.

As McGilligan has it, Brooks’s defining qualities—exuberance, charm, anger, and a deep insecurity—were all present in his teenage years. Brooks was “always on,” his classmates recalled; he was “the class shmendrik.” Brooks’s own judgments were just as harsh: He considered himself “short and ugly,” a mincing “Hebrew chipmunk.” At some point, Brooks realized that insecurity could serve his comedy. “Here I am, I’m Melvin Brooks!” he sang to Catskills crowds, as if daring them to ignore him. His routine ended with a naked plea: “Out of my mind, Won’t you be kind? / And please love Melvin Brooks!” He finished kneeling, arms outstretched, as if ready to hug or be hugged.

Brooks wasn’t book smart, but he possessed a kind of primitive wisdom, knowing in his kishkes that status and respectability—the normal blandishments of middle-class life—weren’t for him. Good instincts. He was, as Funny Man shows, a born comedian. He had quick reflexes, a wonderfully malleable face, and could think seriously about utter silliness. And he possessed an innate self-confidence. The flip side of his insecurity was a stunning grandiosity: Brooks would proclaim his genius loudly. (“Is the genius awake yet?” Moss Hart would ask, years later, on the phone.) On confident days, Brooks called himself “a tough Jew from Brooklyn” and apparently meant it. Once, during his army stint, a soldier called Brooks a “dirty Jew.” Brooks swung his steel mess kit at the man’s face.

Brooks was an incorrigible goofball, but he was fundamentally serious about comedy in a way that mirrored the seriousness of the times. In early 1944, just before D-Day, Brooks enlisted in the army and shipped out to France. Like so many soldiers, he returned scarred, damaged, prone to mood swings and depressions. He’d seen devastated French villages, streets strewn with fresh corpses. The experience “added a layer of outer shell to his personality,” McGilligan writes, insulating him from his own emotions and from other people’s.

Brooks may have been a mess, but he was a charming mess, and a surprising number of attractive women fell under his spell. One of them was a lithe young dancer whom he married in 1953, Florence Baum. Around that time came Brooks’s first big break: befriending Sid Caesar, a brilliant TV comedian whose Jewishness, like Brooks’s, was obvious yet hidden. The attraction to Caesar was powerful. “There’s something big, you know, emotionally missing from my life,” Brooks once said. “[Making] alliances with father figures was always very important to me.” Brooks cultivated Caesar, becoming a “sort of groupie”—really, a stalker—who shadowed Caesar everywhere, pitching sketch ideas. His persistence worked: By the early 1950s, Brooks was writing for Your Show of Shows, a Jewish-in-everything-but-name comedy revue hosted by Caesar.

The Brooks who charmed and bullied his way into Caesar’s writing room left an impression on everyone. Brooks was bumptious, crass, effusive, disruptive, chronically late, and wholly undisciplined. He was also very, very funny and ferociously driven. Funny Man is, among other things, a rather ugly portrait of ambition as a deranging and disfiguring force. Brooks stole jokes, jeered at his fellow writers, and dynamited their work. “I needed a success,” he later said. “I wanted to be famous.” That might explain why, when a senior writer threw lit cigars at his face while yelling “You’re fired!” Brooks didn’t think of quitting.

In the competitive hothouse of the writing room, Brooks was “evasive, unapologetic, belligerent,” McGilligan writes. Often, he was erratic and hostile. “He used to bare his teeth like a rodent if you crossed him,” said a cowriter who recalled his “towering” rages. “That’s not funny!” Brooks would shout during joke sessions. “You don’t know what’s funny!” In more tranquil moods, he delivered his verdict quietly: “All shit.” Serene or volcanic, Brooks radiated anger. Friends withdrew; coworkers urged therapy.

McGilligan shapes his narrative around these episodes; a coy biographer, he withholds insights, revealing character through action and anecdote, like a novelist. As Funny Man makes clear, there were two Mel Brookses: one cruel and peremptory, the other charming and jocular. The second Brooks drew people to him; he was energetic, funny, avid, joyful. He banished boredom from his life and other people’s. (“Oh good! The party’s about to begin,” Brooks’s second wife, Anne Bancroft, would think when Brooks came home at night.) Most of all, he seemed grandly, enviably free saying, doing, and making whatever he wanted. People loved sharing that freedom. They felt more alive in his presence.

The delightful Brooks, such grand company, gets short shrift in Funny Man, elbowed aside by the angry, belligerent Brooks. Beneath anger, there’s usually pain, and in Brooks’s case, there were reservoirs of it. In the 1950s, while writing Your Show of Shows, Brooks suffered frequent nervous breakdowns. There were bursts of hypomania; sudden, acute bouts of mourning; and at least one episode of paranoid psychosis. Finally, Brooks submitted to therapy. “All I did was cry,” he recalled of his psychoanalytic sessions. “For two years. I did nothing but sob.” Brooks’s dark night of the soul lasted six years.

By all accounts, Brooks learned much about himself, trading misery for ordinary unhappiness. What all that therapy didn’t do was change Brooks. He seems to have suffered from a looming sense of emptiness, an affliction not to be therapized away. In the showbiz mindset he carried with him, attention is oxygen; wealth is validation; prizes and praise are sustaining. The problem, McGilligan makes clear, is that no amount of applause could satisfy Brooks; his needs were bottomless. Even after he won an Academy Award for his short film The Critic, Brooks often felt neglected and unappreciated.

By that point, he’d pulled his life more or less together, leaving his wife for the actress Anne Bancroft, a showbiz pairing that somehow worked. With Carl Reiner, whom he had met when they both worked on Your Show of Shows, he created the 2000 Year Old Man, a kvetchy, old Jew based on Brooks’s real-life uncle. In 1968, he filmed The Producers, conscripting Zero Mostel for the Max Bialystock part. At first, Mostel was appalled: How could he, a Jewish actor, play a scheming, vulturous Jew—an antisemitic stereotype? Eventually, though, he yielded to Brooks’s importunate charm. “Mel has great craziness,” he later said, “which is the greatest praise I can have for anybody.”

McGilligan is a shrewd biographer, if somewhat immune to Brooks’s screwball charm. Too bad. A more appreciative approach might have better captured Brooks’s comedy. Brooks called his humor “big city, Jewish” and “energetic, nervous, crazy.” The critic Vincent Canby praised its “lunatic highs”—its speed, volume, risk-taking. Of course, not everyone enjoyed the carnival ride. “He has been conducting a vocal reign of terror,” Pauline Kael, a chatterbox herself, once complained. There was a bullying quality—“laugh, or else!”—to Brooks’s comedy, Kael wrote. It was pushy and excessive. She was gagging on all the gags.

But with Brooks, excess was always the point. An enemy of solemnness, of piety and cant, of repression and restraint, he was built for overflow. Just as surely, Brooks has a counterphobic streak, veering toward danger, accident, and death. Consider the 2000 Year Old Man, whose antic chatter about lion attacks and fried food (equally lethal, he implies) seems like an amulet against anxiety. Long before Seinfeld, it brought a distinctively Jewish voice to mainstream America. At first, Brooks worried it was too Jewish—how would it play in Peoria? Pretty well, actually: The album sold a million copies. To Gentile ears, it didn’t sound Jewish or ethnic. It merely sounded funny.

By that point, he had become “Mel Brooks,” having abandoned Melvin Kaminsky somewhere along the Palisades Parkway en route to the Catskills. This act of self-creation was also, of course, an act of distancing, a farewell to Jewish Brooklyn. It was, per McGilligan, a brief, ambivalent farewell; Brooks, in classic Jewish fashion, gradually returned home to his ethnic roots. After the 50s, Brooks never assimilated or concealed his Jewishness. He was proudly, emphatically Jewish. America assimilated him.

Brooks’s Jewish voice could rise into a Jewish roar. On a dozen memorable evenings, Brooks hijacked the Tonight Show, upstaging Carson with his inspired meshuggene act. Next to Carson—amiable, unruffled, WASPishly suave—Brooks seemed drawn toward self-caricature, the Jewishness turned up to 11. “Gentiles! They’ll drink anything!” he’d yell at Ed McMahon, seizing his coffee mug and spraying its contents at the audience. On another night, Brooks heckles the announcer—“Why don’t you put on a tie, shmendrik!”—and buries him in insults. “We’re going to come right back,” Carson smiles, but Brooks ignores him, refusing to go quietly into that good commercial break. Playing the loud, disruptive Jew seemed a compulsion for Brooks, an act of defiance. “I am a Jew. What about it?” Brooks once said on 60 Minutes. “What so wrong? What’s the matter with being a Jew? I think there’s a lot of that way deep down beneath all the quick Jewish jokes I do.”

The great puzzle of Brooks’s life is his anger, the intense, hair-trigger temper that sent actors scurrying for cover. It’s a riddle McGilligan can’t quite solve, only chronicle, exhaustively, with survivor stories from various writers’ rooms and film sets. Here, Brooks’s battered colleagues get their revenge, recalling tantrums, meltdowns, and 100 varieties of rude, unmenschy behavior. The stories are myriad, yet all alike. As a director, Brooks tyrannized crews, belittled writers, sent actors into therapy, and behaved like he had in Caesar’s writing room. His sets resembled a family where the father had gone crazy.

The roots of Brooks’s anger are surely complex, yet clues are scattered throughout his interviews. “I always felt it was my job to amuse those around me,” Brooks once said. “Don’t ask why.” You don’t need to be a Freudian to see how such a burden could stir up intense resentment, even rage, at an audience. Brooks’s response to critics—those professional withholders of approval and gratitude—often went beyond annoyance into fury. “I have a body of work!” Brooks once screamed at Roger Ebert. “You only have a body.” Deprived of affection, he turned from “Good Mel” into “Rude Crude Mel,” as McGilligan pithily puts it.

Brooks’s serious side, such as it is, came through in his directing. (Brooks wasn’t a writer, strictly speaking, but a talker, a human geyser of dialogue who relied on stenographers.) He certainly was a perfectionist, an exacting editor, a fanatic about casting. Actors earned their roles through intense, exhausting auditions that included long interviews. (“It lasted hours. I felt like I was at the Mayo Clinic,” Madeline Kahn recalled.) Once scripts were prepared, Brooks tolerated no meddling by big-shot producers. Universal’s Lew Wasserman balked at Springtime for Hitler and offered a compromise: Springtime for Mussolini. How would that have worked out? Thankfully, we’ll never know: Brooks refused, dumping the producer. He would mock Hitler into oblivion, he later said.

Brooks seems to have countered every rebuff with similar stubbornness. McGilligan quotes Anne Bancroft: “No man had ever approached me with that kind of aggression.” And: “The man never left me alone.” How might that courtship have gone in 2019, we wonder. Brooks seemed to interpret the word “no” to mean “maybe” or “convince me” and then coaxed, pressured, and hectored until he got his way. Of the Brooks–Bancroft union, McGilligan says little—like all marriages, it is mysterious from the outside—though he implies that Bancroft was a civilizing force, quite a task for any wife, but especially Mel Brooks’s.

Of Brooks’s first marriage, we learn slightly more, none of it pretty. Brooks gave his account in a screenplay, Marriage Is a Dirty Rotten Fraud, written in the messy aftermath. McGilligan portrays a jealous, resentful husband who found marriage stifling (“I needed more attention from the world, and less attention from a wife,” Brooks once said). Though the marriage was a quagmire, divorce freed neither party, certainly not Baum. In McGilligan’s account, Brooks never stopped punishing her, shirking alimony while stashing his millions in dodgy shell corporations. The couple had three children; Brooks maintained an aloof interest in their lives after moving to Hollywood.

Politically, Brooks was a liberal—or so people assumed after Blazing Saddles. In fact, Brooks’s films reveal something else. Brooks’s instincts—his “curious inner compass,” as the critic Kenneth Tynan put it—were mainly comedic: If a joke landed, he used it. On a deeper level, he gravitated toward risk, mischief, transgression—in a word, excitement. At the deepest level was a ferocious need for self-expression. “I’ve got to get this stuff out of my system,” Brooks once said. It was perhaps that simple. His talent needed a vehicle; his manic energy needed an outlet. Lord knows what might have happened had it remained bottled up.

With The Producers (1967), he unbottled it, gleefully tossing every rude, raucous, just plain wrong joke he could think of into the mixture. McGilligan’s account of that film, which gave Brooks his foothold in Hollywood, is wonderful. Arriving on set, Brooks was so nervous he yelled “Cut!” instead of “Action!” on his first take. The entire film seemed doomed, but soon enough, the crew was swept up in Brooks’s reckless audacity. “Oh my god, are we allowed to show this?” the choreographer wondered. Brooks, by being his wild, anarchic self, answered yes, everything is allowed, for me and for you. By most accounts, Brooks was a madman on set, yet even that worked for him. “Brooks’s craziness charged the atmosphere, ramped up excitement on the set,” an actor recalled.

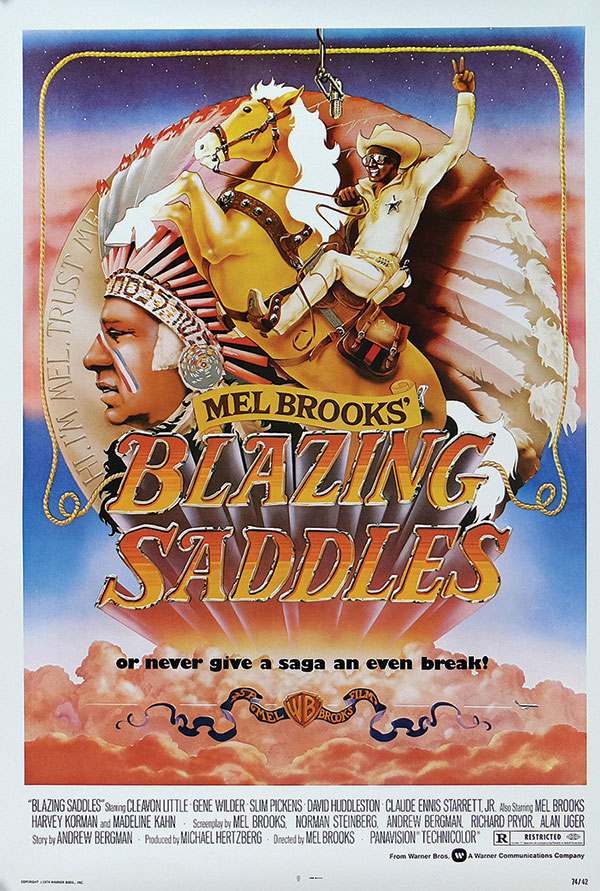

A more confident Brooks began working on Blazing Saddles in 1972. The film skewers Westerns, and with them, the entire mythology of the American West. The writing process was unusually intense. Brooks described it as therapy, but it was more like an exorcism: “It just got everything out of me: all of my furor, my frenzy, my insanity, my love of life and hatred of death.” Though some critics griped—“He can be vicious and get away with it because he is Mel Brooks,” Kael complained—Blazing Saddles was a smash success and a turning point in his career. Brooks had flirted with seriousness in an earlier film, The Twelve Chairs, but from Blazing Saddles onward, he aimed for mass appeal. “I’m just becoming a crowd-pleaser,” he shrugged. “What have I got to say?”

The answer was 1977’s High Anxiety, his parody/homage to Alfred Hitchcock. “I don’t want to sacrifice a single laugh,” Brooks told critics, and in the spirit of excess, he crammed it with crude gags and clever allusions. It didn’t quite work. Both Mel Brookses were present, the needy, love-starved child—“Please love Melvin Brooks!”—and the angry, bellicose teenager. “He wants to offend, and he also wants to be loved for being offensive,” Kael griped. Overall, the response was mixed, but Brooks was pierced, falling into a depression surely made worse by his high expectations. As he told Kenneth Tynan before the film’s premiere, “When people see this, I want them to say, ‘He may be just a small Jew, but I love him. A short little Hebrew man, but I’d follow him to the ends of the earth.’”

For all its liveliness, Funny Man can feel somewhat dutiful. What it doesn’t do—it would have been a tall order—is capture the sheer manic vitality of Brooks’s best comedy. For that, you’ll need Amazon Prime or YouTube, or your own memory reel. It’s easy enough to imagine a theater filled with Brooks’s inspired creations: the flatulent cowboys; the Yiddish-speaking Indians; campy, singing Nazis; the wan inmates of The Psycho-Neurotic Institute for the Very, Very Nervous. Nearby, a clumsy, bewildered Moses drops the 15, make that 10, commandments. And, talking over them all, is the 2000 Year Old Man, oozing ire and venting shpilkes.

Even second-rate Brooks has its goofy delights. I’ll never stop laughing at Brooks’s cameo as a Rabbi Tuckman—“purveyor of sacramental wine and mohel extraordinaire!”—in the harmlessly nutty Robin Hood: Men in Tights. Entering Sherwood Forest, his mule ambles along in a loose zigzag. “You’re fershnikit!” he taunts the creature, wagging a rabbinical finger. “You drunken mule, you!” To the Merry Men, he explains what mohels do, using a tiny guillotine as a prop. They become suddenly less merry.

If Funny Man neglects Brooks’s comedy, it also sidesteps its many meanings. True, explaining humor is almost always a bad idea. Still, a little analysis wouldn’t have killed McGilligan (or his readers). Brooks’s comedy raises serious questions, or perhaps varieties of the same question. Who deserves mockery? Should comedy have a moral center? Are some subjects so serious they shouldn’t be turned into a joke? Is anything off limits? These issues never bothered Brooks, and Funny Man is similarly untroubled by them.

If Funny Man feels slight despite its heft, then in a curious way, it mirrors its subject. For nearly 500 pages, we’re in the company of a tireless showman, always performing. The real Brooks, whoever he is, doesn’t get much stage time apart from his meltdowns and rages; there is little sense of who he might be in quiet moments, alone with himself. Then comes a singularly revealing moment that also suggests why this biography must have been almost impossible to write. On page 482, Brooks’s former publicist notes that

In private, Mel turned off. No personality, deadpan, sullen. It wasn’t rude. But without an audience, he just turned miserably blank, which no one who saw him publicly would believe.

Quite clearly, Brooks was incapable of seeing himself in those moments; he could only see himself through other people, through their adoring gaze. It’s equally obvious that, in some fundamental way, Brooks never fully developed; in his lifelong rush toward success and applause, he never cultivated the parts of himself that would have added depth to his personality. Indeed, you can’t help notice how woefully narrow Brooks’s life seems, how empty of commitments, convictions, and compassion. McGilligan, losing his patience, labels this “solipsistic”—a painfully accurate term for Brooks’s self-enclosed universe.

A bit of that rubs off. What this long biography lacks, finally, is the quality of human sympathy. Brooks offers none—it isn’t in his character—and he elicits none, not from friends, fellow writers, or his biographer. McGilligan is unimpressed: Having seen too much of Bad Mel, he won’t be charmed by Good Mel. Some readers may muster more compassion for the adult Brooks—like the child, growing up fatherless, with an apprehension of death, he surely deserves our sympathy. And yet, Brooks, selfish and self-concealing, is a hard man to sympathize with.

By the 1980s, Brooks’s long career was winding down, his firecracker talent fizzing out. It seemed spent by the 1990s, then rebounded dramatically in 2001, when The Producers conquered Broadway. By then, Brooks had achieved comedic sainthood and Emmy, Oscar, and Grammy awards. “I never leave show business. It’s in everything I do,” Brooks once said, and he kept his word, though, in a way, Brooks had made himself redundant. His 70-year war against decorum was over; everything crude, vulgar, and offensive was now mainstream; Brooks’s juvenile gags now seemed positively wholesome compared to the gross-out shenanigans of younger comedians. The culture was more Brooksian, yet, somehow, it was no place for an aging vaudevillian.

Brooks is 93, alive and quipping, still popping up on stage. “As far as anyone can tell, he is unaltered,” David Denby observed last winter. Brooks may be a genius as H. L. Mencken defined it—someone who holds onto childhood. But genius is sometimes boring on the page, grey and inert. Still, McGilligan deserves credit for writing a smart, clear-eyed, revealing biography, devoid of unearned sympathy. He resists charisma. He isn’t charmed by charm. Sound of mind, he’s cool, not kind, and won’t love Melvin Brooks.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Jews on the Loose

If fame is when everyone understands it is you when only your first name is mentioned, Groucho (Marx) certainly qualifies.

The Great Whitefish Way

Larry David baked an anything-you-can-do-I-can-do-meta stance into Fish in the Dark from the get-go.

Jokes: A Genre of Thought

Three people are required to perfect a joke: one to tell it, one to get it, and a third not to get it.

No Joke

Sigmund Freud loved Jewish jokes and for many years collected material for the study that would appear in 1905 as Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious. An excerpt from Ruth Wisse's new book No Joke: Making Jewish Humor.

Ahad Haamoratsim

One of my favorite gags in Blazing Saddles appears only on the lobby card, where the beadwork on Indian headdress spells out Kasher l’Pesach (“Kosher for Passover”) in Hebrew letters.

asmith

Thanks for pointing that out!