Jonah: The Sequels

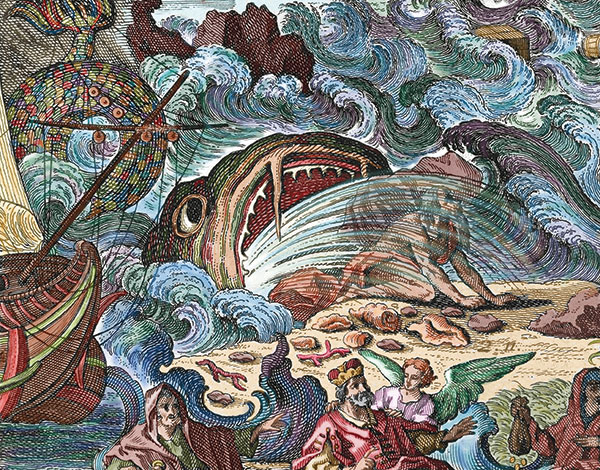

In 1896, the New York Times, citing the October 1891 issue of the British South Yarmouth Mercury, told the fantastic tale of a sailor on the whaling ship Star of the East who was amodern-day Jonah:

One morning the lookout sighted a whale about three miles away on the starboard quarter. Two boats were manned. In a short time, one of the boats was near enough to enable the harpooner to send a spear into the whale, which proved to be an exceedingly large one. . . . [It] beat about with its tail in the maddest fashion. The boats attempted to get beyond the reach of the animal, which was apparently in its death agonies, and one of them succeeded, but the other was less fortunate. . . . The men were thrown into the water, and, before the crew of the other boat could pick them up, one man drowned and James Bartley had disappeared.

Though the whale succumbed to its wounds, a search for the missing sailor turned up empty-handed. That is, until, with their “axes and spades,” the men cut open their defeated prey and were startled to find Bartley, folded over and unconscious. He was “treated to a bath of sea-water” and revived. His skin, having been subjected to his temporary host’s gastric juices, “underwent a striking change.” His hands and face “were bleached to a deadly whiteness and his skin was wrinkled, giving the man the appearance of having been parboiled.”

In a learned, entertaining 1991 article, Edward Davis traced the fascinating afterlife of the story of Bartley’s whale-intestinal adventure, which had been used as proof of the Jonah story’s plausibility in the Princeton Theological Review and elsewhere. He also showed that the South Yarmouth Mercury never existed.

Over the last two millennia, Jonah’s tale has been retold for various purposes. In his Antiquities of the Jews, the first-century turncoat Josephus promised his Roman readers that he would tell the story as he had found it “written down in the Hebrew books.” He then proceeded to offer, like poor Bartley’s skin, something barely recognizable.

While the first chapter of Jonah does not yet give the exact message Jonah was meant to deliver to the sinful Ninevites, Josephus spells it out for us: Jonah was “to publish it in that city, how it should lose the dominion it had over the nations.” Josephus explains Jonah’s flight from this mission, which has bewildered exegetes for ages, as the result of Jonah’s fear of harm at the hands of the Ninevites angered by the prediction of their downfall. Josephus’s account of the storm that affected only the boat on which Jonah fled, and the subsequent lottery by the panicking passengers to divine the storm’s cause, is relatively faithful. Jonah’s speech about the Lord who “created the sea and land” is toned down, and the sailors’ vows to give offerings to Jonah’s God after they toss him overboard are dropped. Louis Feldman, the late scholar of all things Josephus, suggested that these tweaks were a result of political caution. Josephus was wary of giving his pagan readership even a whiff of Jewish proselytizing. (As Feldman used to quip to decades of students at Yeshiva University, “Josephus was a smart man, but I would never have wanted to buy a used car from him.”)

Chapter Two is retold somewhat faithfully, although Josephus omits Jonah’s prayer from the fish’s belly and credits him with obtaining a forgiveness he never asked for. It’s when Josephus sails on to the second half of the book that he jumps the shark. The book’s last two chapters are reduced to three sentences: Jonah delivers his message of impending downfall, “and when he had published this, he returned.” “Now,” says Josephus as he rests his stylus, “I have given this account about him as I found it written.” The repentance of the people (and animals) of Nineveh, arguably the book’s climax, is missing. Nor is there any hint of Jonah’s sulking response to their teshuvah. In Josephus’s account, the kikayon, the short-lived, shade-providing plant for the sweltering Jonah, never grew, let alone shriveled. And God’s great rhetorical question, “And shall I not care about Nineveh, that great city, in which there are more than one hundred and twenty thousand persons who do not yet know their right hand from their left, and many beasts as well?” was never posed.

Feldman offered a series of explanations for these elisions. The notion of a world power repenting after a warning from Israel’s God was to be avoided (me, proselytize? Never). And Jonah’s disappointment over the survival of a pagan city probably wouldn’t have gone over well with readers in a pagan city. What of God’s resonant last speech about mercy? How could Josephus justify cutting it? As Yitzhak Berger observed in Jonah in the Shadows of Eden, although the last sentence of the book has been read by the Jewish tradition as a rhetorical question, it can also be read declaratively: “And I shall not have mercy on Nineveh.” Maybe Josephus read it that way. Thus, Jonah had overcome his fears (with a little help from a fish) and delivered the message, which God’s speech merely confirmed, and Nineveh had eventually fallen. After all, Josephus was working on his rewrite from a Roman estate, not an Assyrian estate.

Such a calculated rewriting of the Bible may offend modern readers, but the ancient Rabbis also rewrote Jonah’s last scene, as Robert Gregg has noted. When the book of Jonah is read aloud on Yom Kippur, it doesn’t end with God’s caustic moral rebuke to the prophet, either. It ends this way:

Who is a God like You, forgiving iniquity and remitting transgression; Who has not maintained His wrath forever against the remnant of His own people, because He loves graciousness! He will take us back in love; He will cover up our iniquities, You will hurl all our sins into the depths of the sea. You will keep faith with Jacob, loyalty to Abraham, as You promised on oath to our fathers in days gone by.

These verses about God’s loving-kindness are actually from the seventh chapter of another “minor prophet,” Micah. Placed there by the Rabbis, they become Jonah’s response to God. “Shall I not have mercy on Nineveh?” God had asked. And the Yom Kippur response is delivered, “Who is a God like You, forgiving iniquity and remitting transgression . . .”

The Rabbis, as James Kugel has shown, read the Torah as a unified, self-glossing canon. Thus, Micah’s words could very well have been, on some level, Jonah’s, or at least about him, especially since they speak of hurling “all our sins into the depths of the sea.” Yom Kippur, the Rabbis saw, was not a day for rhetorical questions, so they copied and pasted the answer from Micah. On this day, even the pouting prophet must speak of God’s gracious response to His people’s repentance.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Sitting with Shylock on Yom Kippur

The poet Heinrich Heine imagined the merchant of Venice attending Neilah, the final service of Yom Kippur, but I find him earlier in the day, at Mincha, and we are listening together to the story of another Jew among Gentiles, bitter at being compelled to show mercy.

“Repent, Repent”

In his new book, How Repentance Became Biblical: Judaism, Christianity, and the Interpretation of Scripture, David A. Lambert argues that repentance, as we understand it today, is absent from the Hebrew Bible.

Is Repentance Possible?

And should we add a confession on Yom Kippur “for the sin of opening browser windows of distraction”? On Aristotle’s akrasia and Maimonides’s teshuvah.

Biblical Start-Ups

A prominent Israeli novelist on novelties in the Bible.

Samuel Heilman

I like Halpern's fine article, but since he mentions Kugel, I would add the Kugel has argued Josephus is a gloss on the Biblical text. It is quite possible that what Josephus writes was what many Jews at the time believed was the true story of Jonah. Just we have learned to take Rashi and other commentators as a key to how to understand the Bible, we can probably see in Josephus , as Kugel persuasively argues, as how his contemporaries or immediate predecessors read the Jonah text.