All That Is Solid

From Oedipus Rex to Richard III, playwrights have been drawn to tragic downfalls. The failure of a bank doesn’t seem quite as stageworthy—not even when the bank is Lehman Brothers, a century-and-a-half-old institution that collapsed in the space of a week in September 2008. The story is certainly of historic importance; Lehman’s Chapter 11 filing was the biggest in American history, involving more than $600 billion in assets. More, it was the moment when the subprime mortgage meltdown turned into a global financial crisis, whose effects on politics and the economy are still being felt today. The Battle of Bosworth Field, where Shakespeare’s Richard offered “My kingdom for a horse”—a kind of 15th century credit default swap—was a local squabble by comparison.

But it’s far from obvious that the story of Lehman Brothers is material for a play, much less a hit. It took a keen theatrical instinct for the Italian writer Stefano Massini to seize on the story right away, beginning work in late 2008 on what would become The Lehman Trilogy. The project went through several incarnations: first written as a novel in verse, it was adapted for an Italian radio play, which turned into a French stage play, before ending up as a highly acclaimed English stage version, directed by Sam Mendes at the UK’s National Theatre in 2018. That production came to New York for a brief run in 2019 and was scheduled to open on Broadway when COVID-19 canceled the season.

Now Massini’s original novel has been translated into English by Richard Dixon, bringing the career of The Lehman Trilogy full circle. The stage version is long, three and a half hours in English, but the novel is even longer, 720 pages. Fortunately, the length is not owed to detailed explanations such as the collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) the bank used to disguise bad mortgages as good investments. That story has been told in a number of nonfiction books with ominous titles like The Devil’s Casino and A Colossal Failure of Common Sense.

In fact, while the fall of Lehman Brothers inspired Massini, it’s barely depicted in The Lehman Trilogy. That’s because Massini isn’t telling the story of the firm so much as of the family behind it, and the last Lehman to run Lehman Brothers died in 1969. Massini’s book effectively ends with the death of Robert “Bobbie” Lehman—except that in this version he achieves a kind of apotheosis, dancing the twist into eternity:

For Bobbie in the end is convinced:

now he is sure

he is quite certain

he cannot die.

The patriarchs died, yes

but at the age of 500, 600, 700

if not more

which is like saying

they too

were immortal

like the bank

and it is right

so right

since HaShem cannot allow

anyone who leads a Chosen People

to die.

Massini’s conflation of banking with Judaism and Lehman Brothers with the children of Israel can’t be pinned on the actual Robert Lehman. Born in 1891 into the family’s third American generation, he left behind the milieu that the historian Stephen Birmingham called “Our Crowd”—elite German Jewish business dynasties like the Schiffs, Guggenheims, and Strauses, who worshiped at Temple Emanu-El, New York’s first Reform synagogue. Robert Lehman’s lengthy front-page obituary in the New York Times mentions Hotchkiss and Yale, his stable of racehorses, and his world-class art collection, whose Rembrandts and El Grecos are now in the Metropolitan Museum’s Robert Lehman Wing. The word “Jewish” doesn’t appear once.

That obituary tells a story about assimilation and social climbing that could make for a fascinating novel, but it’s not the story Massini wants to tell. The play and still more the novel don’t aim at historical or psychological realism. They are mythic in scale, using three generations of the Lehman family (one per section of the “trilogy”) as characters in a didactic pageant about capitalism, America, modernity—and Jewishness, which plays an unsavory role in the proceedings.

One of the things that makes The Lehman Trilogy distinctive on stage is that there is no dialogue. Rather than enacting scenes, the three actors who make up the entire cast function as a chorus, narrating the story with the assistance of a basic set and a few props. Likewise, the novel eschews traditional dialogue and scene-setting, aiming instead at an epic’s scope and elevation. It’s even written in verse, and while Dixon’s translation reads like prose with arbitrary line breaks, it does capture Massini’s rhetorical and imagistic flights:

To live in America, to live properly,

you need something else.

You need to turn a key in a lock,

you need to push open a door.

And all three—key, lock, and door—

are found not in New York

but inside your brain.

So reflects Heyum Lehmann, who lands in Manhattan in 1844 and promptly has his name changed by a customs official to Henry Lehman. The novel’s opening scenes of a discombobulated immigrant in New York are familiar from many American Jewish stories, but this one soon takes an unusual turn. The third chapter finds Henry behind the counter of a dry goods store in Montgomery, Alabama, selling “seersucker / chintz / flag cloth / beaverteen / doeskin that looks like deer” to nearby planters. Soon he is joined by his brothers Emanuel and Mayer, who leave their father’s house in Rimpar, Bavaria, to start over in the promised land.

Millions of immigrants made similar journeys in the 19th century, but few actually found the streets they walked to be paved with gold. The transformation of the Lehman brothers’ little shop into Lehman Brothers, the financial behemoth, happened in several stages. First the brothers had the idea of taking payment for their goods in cotton, which they sold to factories for processing. Soon they were large-scale cotton brokers, managing to survive the disruption in the cotton trade caused by the Civil War and branching out into other commodities such as sugar, coal, and oil.

By then, Henry was gone—he died in 1855 at the age of 33—and Emanuel and Mayer relocated the firm’s headquarters to New York, already the financial center of the United States. When Emanuel’s son Philip took charge of the firm, in 1901, commodities trading took a back seat to investment banking, with Lehman underwriting the stock issues of some of the defining companies of the American century: Sears Roebuck, RCA, Pan Am. Under his son Robert’s 44-year reign, the firm weathered the Great Depression and emerged even stronger. Only after his death did Lehman Brothers get its first CEO from outside the family—Pete Peterson, who appears in a fanciful cameo in The Lehman Trilogy as a young boy working at his family’s Greek diner in Nebraska.

One way of thinking about the Lehmans’ 120-year run is as a lucky convergence of talent and opportunity. Abraham Lehmann, the father of Henry, Emanuel, and Mayer, was a cattle dealer in Bavaria; maybe he too had a genius for commerce, but he had nothing to trade but cows. His sons came to America just when its industrial economy was being built from scratch—largely on the backs of slaves, whose labor in Alabama’s cotton fields was the ultimate basis of the Lehman family’s fortune. (The Lehmans also owned slaves themselves, though Massini barely mentions it.) The young country had a great need for businessmen who knew how to connect producers with consumers, resources with markets, investors with entrepreneurs. For three generations, the Lehmans showed a genius for making such connections.

The problem for The Lehman Trilogy is that while Massini recognizes this achievement, he also deeply disapproves of it. Early in the book, when Mayer proposes marriage to Babette Newgass, he tries to convince her father that he has a respectable occupation. But he has trouble describing what exactly Lehman Brothers does:

“We’re right in the middle

Mr. Newgass.”

“What sort of job is that

being in the middle?”

“It’s an occupation that doesn’t yet exist

Mr. Newgass:

we’re the ones who are starting it.”

The word “middleman” might be new, but, of course, the role existed long before the Lehmans came along, and it has always inspired suspicion. The slaves who grew the cotton worked hard for nothing, and the factory workers who made it into cloth worked hard for very little, but the Lehmans got rich without seeming to work at all. As Massini writes in the voice of Mayer Lehman: “First: when we were in business / people gave us money / and we gave something in exchange. / Now that we’re a bank / people give us money just the same / but we give nothing in exchange. / At least not for the moment. Then we’ll see.”

Using money to make money—that is, investing—was viewed with suspicion until the fairly recent past; Judaism, Christianity, and Islam all banned usury. Doing away with this taboo was a prerequisite for the emergence of capitalism, which brought unprecedented improvements in the quality of human life. But suspicion of finance has never disappeared. It’s a major fuel for populist movements, as when William Jennings Bryan accused American bankers of crucifying mankind upon a cross of gold. That was in 1896; in 1934, Bryan’s granddaughter Kitty married Robert Lehman, a nice parable of the usual fate of populism in America.

The Lehman Trilogy is particularly informed by the idea that capitalism degrades humanity by turning everything into a commodity with a price. This charge is as old as the Industrial Revolution itself: “Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers,” Wordsworth complained in 1807. Massini’s Lehmans are monomaniacs of profit, devoid of emotion and obsessed with numbers. Several characters are capitalist idiot savants.

Philip Lehman, for instance, considers 12 women as marriage prospects and assigns them each a score out of 200, marrying the one who scores highest. A next-generation Mayer Lehman, distinguished from the founder by the nickname “Dreidel,” spends decades refusing to speak before revealing that he has been preoccupied with counting the words he hears: “The first year I spent in here / there were three words on everyone’s lips: / 21,546 times you said EARNINGS. / 19,765 times I heard INCOME. / 17,983 times RECEIPTS.”

Meanwhile, Dreidel’s cousin Arthur calculates “that every American / owes his bank / a lump sum figure / of somewhere around 7 dollars and 21 cents” (a nonsensical statement) and begins to think of everyone he sees as “a 7.21” in a mathematical formula:

Those 7.21s also go to church

And pray to a God (J) who in moral terms

Is comparable to

—or, at most, one step above—

Lehman Brothers;

He’s the creator of 7.21s, but we are their financiers.

Of course, the characters in The Lehman Trilogy are under no obligation to resemble their real-life namesakes—that’s Massini’s privilege, and no doubt Richard III would have a bone to pick with Shakespeare. But it’s worth noting that the actual Arthur Lehman, who died in 1936, was a founder of the Federation of Jewish Philanthropies, a predecessor of today’s UJA-Federation, and a major benefactor of the New School for Social Research. A charitable, community-minded man, he didn’t walk around thinking that he was God and other human beings were worth $7.21. No one has ever done that, except perhaps in an insane asylum.

But the point of The Lehman Trilogy isn’t to depict actual human beings or even an actual business. It’s to dramatize a thesis about the dehumanizing power of capitalism, which turns relationships into transactions. The most famous statement of this idea was made by Karl Marx in his Communist Manifesto: “All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind.”

Marx was born in Trier, Germany, in 1818, three years before Henry Lehman was born in Rimpar, about 200 miles away. Their contrasting roles exemplify a rift that had enormous consequences for Jews, and for the way the world thinks about them. In 1844, the same year Henry Lehman arrived in America, Marx published his essay “On the Jewish Question,” putting a new Communist spin on an old Christian idea by arguing that the redemption of the world required abolishing Judaism. “What is the worldly religion of the Jew? Huckstering. What is his worldly God? Money. Very well then! Emancipation from huckstering and money, consequently from practical, real Judaism, would be the self-emancipation of our time,” wrote the grandson of two rabbis.

The Lehman Trilogy draws a similar equation between Judaism and capitalism, repeatedly using the imagery and vocabulary of one to describe the other. This tendency was toned down somewhat in Sam Mendes’s version of the play at the National Theatre, but in the novel, it is unavoidable. When Philip Lehman is asked by a journalist what Lehman Brothers’ business really is, he responds: “Normal people, you see, / use money just for buying. / But those—like us—who have a bank / use money / to buy money / to sell money / to loan money / to exchange money.” Massini prefaces this hymn to money with a description of how Philip “raised his voice / and commented on the Scripture / like a young boy at his Bar Mitzvah / about to be received among the adults of the Temple.”

Another Lehman, Sigmund, starts out as weak-willed and ineffectual until his brothers give him a list of 120 maxims to repeat daily as a drill in ruthlessness. These consist of sayings such as “Better to lie than to disappoint,” “Don’t spare your enemy for what he wouldn’t spare you,” and “Honesty is an abstract concept.” The drill works, and Massini writes that Sigmund is “transformed into a cobra / thanks to the mitzvot of a banking Torah.”

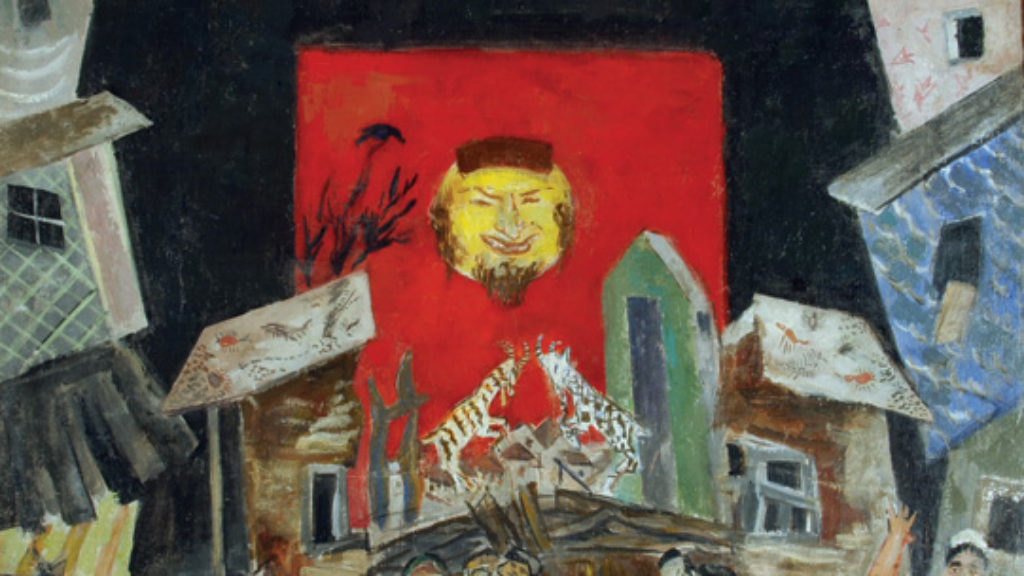

And so on. The New York Stock Exchange is “a synagogue / with ceilings higher than a synagogue.” Lehman Brothers’ publicity strategy is “the bank’s new Talmud.” Business successes are greeted with cries of “Baruch HaShem,” and at the end of the book, the ghosts of Lehmans past gather to recite Kaddish for their dead bank. “This is the famous Wall-Street tribe / bloodthirsty, cruel people / known for their human sacrifices,” says a figure in a dream-scene parody of King Kong, with Bobbie Lehman playing the role of the ape.

Massini seems to intend such conflations of Judaism and capitalism as a critique of the latter rather than the former. In The Lehman Trilogy, Jewish practice is one of the humane things that melts into air under capitalism; for instance, full-fledged mourning in the family’s early years shrinks to a perfunctory moment of silence in the later ones. Massini is a Catholic, but he prides himself on his Jewish knowledge, referring to mourning as “shiva and sheloshim” and giving most chapters Hebrew or Yiddish titles. (The one in which Bobbie Lehman blasphemously calls himself immortal is titled “Egel haZahav,” the golden calf.) But these signs of affection for Judaism strike a discordant note in a story that refurbishes the old tropes of left-wing antisemitism for a new audience.

Suggested Reading

Saladin, a Knight, and a Jew Walk Onto a Stage

Outside of Germany, Nathan the Wise is one of those works more often read than performed, and more often read about than actually read.

Chasing Death

The director of the landmark documentary Shoah, Claude Lanzmann, has written a memoir, which sheds new light on his death-defying life.

Playing the Fool

Of the many varieties of anti-Semitism, or anti-Judaism, that have plagued the Jews over the centuries, two recurrent general patterns can be identified by the holidays that celebrate triumphs over them: Purim and Hanukkah.

A Season of Tzuris: The Shtisels Return

In Season 3 of the hit Netflix show, the Shtisels reckon with an endless procession of trials and tribulations, from the perils of courtship to the strains of fraying marriages.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In