An Entrepreneurial American

I spent most of my teenage years in the company of Harry Houdini, or rather, of his paraphernalia: handcuffs, straightjackets, the Water Torture Cell, and scores of posters advertising his exploits. How did that happen? To borrow a trope from the Ethics of the Fathers: Houdini created his illusions and handed them down to his brother Hardeen, Hardeen sold them to the Amazing Dunninger, and Dunninger sold them to—my father. My father and his partners then built the Houdini Magical Hall of Fame in Niagara Falls, Ontario.

My family owned Muller’s Meats, a business located on Centre Street, a half-block from Clifton Hill, the main tourist strip packed with attractions, including Madame Tussaud’s Wax Museum. They were entrepreneurs, and by 1967, the year of my bar mitzvah, the meat business had outgrown its quarters and moved to a location in a more industrial part of town. That left the Centre Street property empty and, from a business perspective, an unused resource.

My bar mitzvah party took place in a hotel on Clifton Hill in June. Shortly thereafter, my father chanced upon an article deep in the interior of the August 27 edition of the New York Times. It reported that Joseph Dunninger, a famed magician and mind reader, was selling his collection of some five thousand items, many from Houdini and other magicians of his era. It occurred to my father that the collection might be turned into a tourist attraction in the space on Centre Street where Muller’s Meats had stood. My mother agreed. Three days later, they bought the collection from Dunninger. After two decades in the meat business, my family was also in the magic business.

Thus was born the Houdini Magical Hall of Fame. It exhibited a score of magic illusions, most used by Houdini, some that he had purchased from other great magicians of his day, as well as the many handcuffs, locks, straightjackets, trunks, and mailbags he had accumulated for use in his acts. Sidney Radner, an amateur magician who owned Houdini’s Water Torture Cell, agreed to loan it to the exhibit—or “the museum,” as we called it. The highlight of the grand opening in 1968 was James “the Amazing” Randi, a magician and escape artist. Blindfolded and with a hood tied over his head, Randi drove the town’s mayor from city hall to the new museum in an open limousine (I remember the mayor looking uncomfortable). Then, on the street in front of the museum, Randi replicated one of Houdini’s most famous feats: tied in a straightjacket, he was hoisted upside down by a crane. High above the crowd in the street, he twisted and writhed until, finally, he liberated himself from the jacket and was lowered to the ground. It was thrilling to watch. (Like Houdini, Randi would later make a name for himself as an exposer of psychics and other hoaxers and was eventually awarded a MacArthur “Genius Grant” Fellowship.)

When visitors exited the exhibit, they entered a gift shop, where magic tricks were for sale. They were pitched by a live magician—sometimes a professional magician, sometimes me or one of my siblings. (My brother David recently wrote a memoir about our somewhat unusual childhood called Growing Up with Houdini.) Lamentably, in 1995, a cigarette butt carelessly tossed in the trash by the person closing up the museum for the night ignited a fire, which destroyed much of the collection.

While it lasted, the museum brought our family into contact with a stream of personalities from the world of magic. From the older generation, there was Dunninger himself, who had performed for American presidents, and Al Flosso (actually Albert Levinson), the owner of the most famous magic shop in the United States. Among the younger generation were the escape artist David Copperfield (David Seth Kotkin) and the master of close-up magic, Ricky Jay (Richard Jay Potash). One couldn’t help but notice that many of them were Jewish. Even James Randi, who was not Jewish, gave off a Yiddish vibe, probably from having consorted with Jews for much of his professional life. That association of Jews with stage magic was even more true in Houdini’s day. Among his colleagues were “The Great Leon” (Leon Harry Levy), a star of vaudeville; the sleight of hand master Nate Leipzig (Nathan Leipziger); Max Malini (Max Katz Breit), who gave a command performance at Buckingham Palace; and “Okito” (Tobias Bamberg), the scion of a family of Dutch Jewish magicians.

Houdini himself was the founder and president of the Rabbis’ Sons Theatrical Benevolent Association, a philanthropical society that brought together the sons of rabbis and cantors in the theatrical world. Its vice president was Al Jolson (Asa Yoelson), its secretary, Irving Berlin (Israel Baline). He was also a member of the Jewish Theatrical Guild, the president of which was the German-born theatrical agent William Morris; the vice president was Eddie Cantor (Isidor Iskowitch). In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, popular entertainment was free of the restrictions and prejudices that kept Jews out of more established industries. At the height of his career, Harry Houdini was among the most famous Jews in the world.

Houdini lived at the intersection of Jews, magic, entertainment, and entrepreneurship, so it is apt that Adam Begley’s biography appears in the Yale Jewish Lives series. The Jewish historical background is not Begley’s forte: he has a vague sense that Houdini’s father, who emigrated from Hungary in 1876, came from “the Old World,” having “escaped the bloody pogroms and the laws that regulated where he could live and what work he could do.” Hungarian Jews had, in fact, achieved full legal equality in 1867; they could live and work wherever they pleased. Nor were there pogroms in Hungary. Houdini’s parents immigrated to America not to escape religious persecution but to improve their material status (an entirely honorable motive).

But if matters Jewish are not Begley’s strong suit, neither, he argues quite rightly, were they Houdini’s. Houdini: The Elusive American has much to recommend it. Begley has digested and made accessible the existing scholarship on his subject and is particularly strong in evoking scenes of the remarkable, death-defying escapes that defined Houdini’s career as an entertainer.

Harry Houdini was born Erik Weisz (soon “Americanized” to Ehrich Weiss) in 1874 in Budapest. His father, a rabbi who seems to have been trained at least in part in Germany, immigrated to the United States in 1876 after he had secured a rabbinic post with the tiny Jewish community of Appleton, Wisconsin. Two years later, his wife and two children joined him. But after four years there, the nascent congregation decided not to renew Rabbi Weiss’s contract, perhaps because of his lack of English. At age fifty-three, he moved his wife and seven children to Milwaukee in search of work. By the time of Ehrich’s bar mitzvah, the family had moved to New York City, where both father and son found work in the garment trade as necktie cutters. Rabbi Mayer Samuel Weiss died a poor man in 1892. His son would move from the rag trade to riches.

Motivated in part by the need to help support his family, in part by his own inclinations, Ehrich left school at about the time of his bar mitzvah. After reading a biography of the greatest magician of the mid-nineteenth century, the Frenchman Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin, he resolved to become a magician and christened himself “Houdini.” By the time of his father’s death, eighteen-year-old Ehrich had boxed, raced, and been a trapeze artist in circuses, picking up a combination of skills that he would soon put to novel use. Working in dime shows and circus sideshows, he studied the techniques of “freaks.” From an armless man, he learned to use his toes in a prehensile way; from a Japanese balancing act, how to swallow objects and regurgitate them at will; from contortionists, how to manipulate his body in confined spaces—skills essential to hiding the lockpicks and keys that would allow him to escape from handcuffs and locks of every kind.

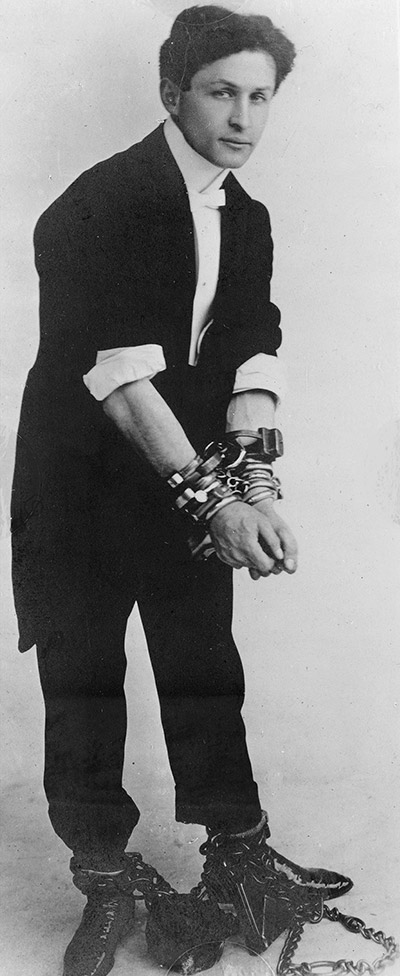

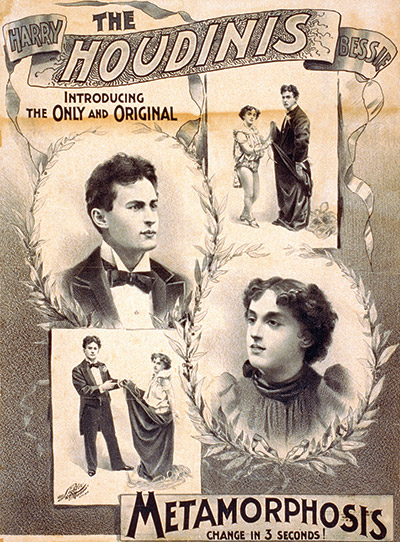

When he was twenty, Houdini married a young dancer, Bess, a nonpracticing Catholic, who assisted him in his act. His devotion to her was surpassed only by his dedication to his mother, Cecilia, whom he supported until the end of her life. His big break came five years later, in 1899, when Martin Beck, a leading theatrical agent (and another Jewish immigrant from Austria-Hungary), saw Houdini perform his handcuff escapes and booked him into the Orpheum circuit of vaudeville theaters. Over the next few years, he honed his escape performances to maximize their dramatic impact, moving from handcuffs to straightjackets to jail cells.

Houdini would go to the local police headquarters and ask to be locked in one of the cells, preferably by a high-ranking officer. He would first be stripped to as close to naked as the most minimal modesty would allow and thoroughly searched from head to foot to ensure that he had no keys, picks, or other tools (though he often did). Then, in minutes, he would liberate himself. Upon visiting Washington, DC, for the first time in 1906, he had the authorities confine him to the jail cell that had held Charles Guiteau, the assassin of President Garfield, which was specially equipped with a customized bulletproof door. As soon as had he liberated himself, he proceeded to open the doors of the other cells on death row and rearrange the prisoners. Astonished reporters wrote of his feats, attracting ever-larger audiences to his theater performances.

In 1900, Houdini and Bess sailed for England, followed by a multiyear tour of the Continent, finding tremendous success in Germany, Holland, and even Russia. In 1903, shortly after the pogrom in Kishinev, he visited the city, where, Begley writes, he “saw firsthand traces of the bloody rampage.”

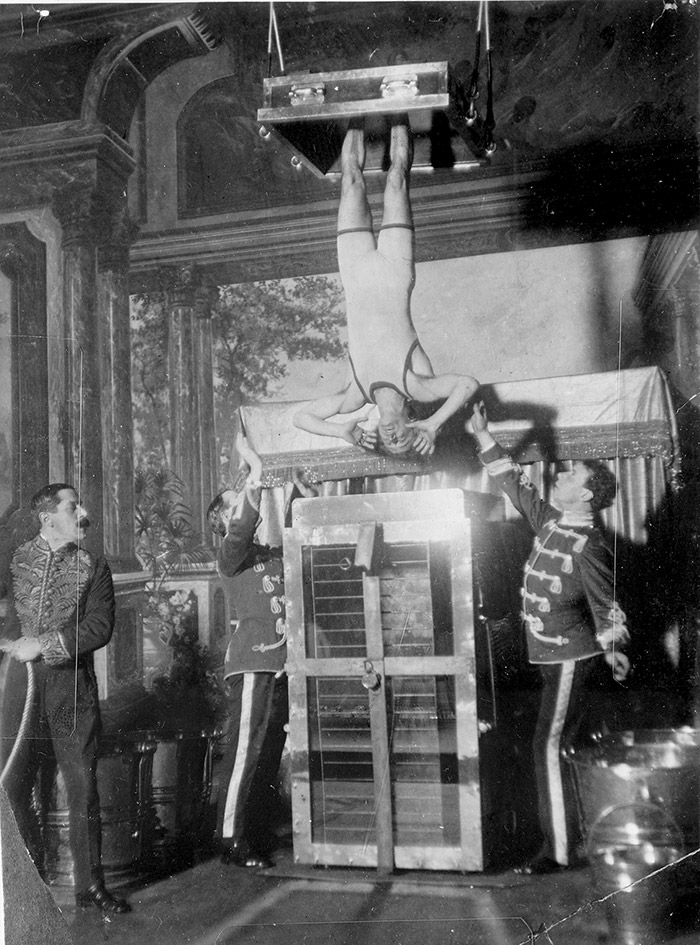

In the two decades that followed, Houdini innovated time and again, straining body and mind for novel challenges that would thrill and astonish his audiences: escaping a large metal milk can that was filled with water and then sealed with multiple locks at the top; jumping off high bridges into ice-cold rivers while manacled and handcuffed; being hoisted upside down from the sides of tall buildings while confined in a straightjacket. In 1912 he introduced the Water Torture Cell:

The gleaming apparatus, made of polished Honduran mahogany, nickel-plated steel, and tempered glass, stood on a tarpaulin spread across the stage. It reeked of menace. . . . The assistants, in brocaded uniforms—which they later covered with shiny black foul-weather gear—looked like acolytes taking part in some sinister sacrifice. . . . The winching up of the victim, the heart-stopping pause before he was lowered headfirst into the water, the sight of him jammed upside down in that glass coffin—torture was the right word. The curtain closed, the excruciating wait began. At the exact moment when the entire audience had become convinced that catastrophe had struck, out he popped, gasping, eyes bloodshot, lips flecked with foam.

Houdini’s fame grew apace. In April 1916, he performed a straightjacket escape in Washington, DC, while suspended high above a crowd of one hundred thousand spectators. President Woodrow Wilson attended his theater performance, and when Houdini visited the Senate, he was invited by Vice President Thomas R. Marshall into his chambers. To publicize an upcoming performance at the Hippodrome in New York City, he again had himself confined to a straightjacket, then hoisted upside down by a subway derrick. High above Seventh Avenue and Broadway, he twisted, struggled, and wriggled his way free, waving the straightjacket in the air to the applause of the throngs below.

In the final, remarkable stage of his career, well captured by Begley, Houdini increasingly devoted himself to attacking the Spiritualist movement and the “mediums” who claimed to be able to contact the dead in their séances. Its most famous advocate was Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. The creator of the rationalistic Sherlock Holmes, Conan Doyle was a marvel of credulity when it came to claims about the supernatural. After trying to dispel Conan Doyle’s illusions, Houdini embarked on a veritable one-man countercrusade. He appeared, unannounced, at Spiritualist demonstrations to debunk their claims, and his stage shows were increasingly devoted to replicating and explaining the trickery by which such mediums attained their effects. Houdini was devoted to astonishing his audiences, but he bridled at those who sought to dupe them by playing upon their longing to be reunited with deceased loved ones.

Writing in the New Republic in 1925, one year before Houdini’s death, the critic Edmund Wilson concluded that “it is characteristic of Houdini that, not content with the ingenuities of illusion and the perfection of sleight of hand, he should have chosen to excel in that branch of magic which was most dangerous, which took him furthest from the theater and which offered most opportunity for the untried.” The key insight here is in that last phrase, and it points to the issue of how Houdini should be understood.

Perhaps the best way to think of Houdini is as an entrepreneur in the sense developed by his contemporary, the Austrian economist Joseph Schumpeter. Usually, when we think of entrepreneurs, we have in mind people like my father: people with an eye for the opportunity to find new or profitable uses for existing resources and a willingness to assume risk. Houdini had those qualities, to be sure. But Schumpeter’s entrepreneur does more. He breaks out of the routine of economic life, in which profits are made by filling the gap between demand and supply by creating a new product that has no rivals (at least in the mind of his customers). In doing so, he creates a monopoly and can rake in much higher gains.

Although Houdini had been a good magician, his talents were not unrivaled. So he created a whole new category of entertainer: the escape artist. The product was himself. His brain he filled with abstruse knowledge of locks and techniques for opening them that surpassed those of the most accomplished burglar. His body he developed time and again to perform feats of dexterity, strength, and contortion. (To prepare himself for his escapes from icy rivers, he immersed himself in his bathtub and had it filled with ice cubes.) He cultivated a dramatic persona and an acute sense of timing. Crucially, he became a master of marketing, closely studying contemporary advertising techniques such as posters and handbills and garnering free publicity through his escapes from public places. Creating demand for the one and only Houdini—that is to say, a monopoly—required not only a huge ego but a good deal of braggadocio.

Intellectuals, who are generally risk averse and tend to value originality in language above all else, are often unsympathetic to entrepreneurs. Begley reminds his readers time and again of Houdini’s lack of schooling and hence his frequent use of ghostwriters to compose his books. He is disturbed by Houdini’s frequent confabulations about his own past (claiming, for example, that he was born in the United States and descended from a long line of locksmiths), as if this was not just show business. Begley calls Houdini “the elusive American,” a play on Houdini’s ability to escape but also on what Begley takes to be the elusive nature of Houdini’s personality. Certainly, his personality was complex, but had Begley seen him as a showbiz entrepreneur in an age when Jews were forging new genres of popular entertainment, he might have found Houdini a little less elusive.

Yet to Begley’s credit, he wisely refuses the temptation to make Houdini’s career an allegory of some larger process or noble purpose. When the Jewish Museum put on a Houdini exhibit a decade ago, the accompanying volume introduced its subject by reminding readers that “liberation from political, racial, or religious oppression was a genuine nineteenth-century aspiration as immigrants traveled via steerage to American harbors and enslaved African Americans made their way to freedom via the Underground Railroad.” Begley, by contrast, avoids such pious pap:

Houdini wasn’t trying to make a case or send a message or save Europe’s Jews. He wasn’t enacting a political or philosophical drama about liberation, let alone liberty. That kind of statement is spectacularly absent from the actual performance and from his own remarks. He liberated only himself. . . . The long list of possible motives behind the escapes and death-defying stunts that made him world famous—a list that stretches from greed and vanity through narcissism and exhibitionism all the way to fear of failure and romantic yearning for transcendence—does not include a desire to improve the lot of his fellow man, or any other altruistic urge.

That is true enough, but it also mirrors the intellectual’s typical propensity to judge the entrepreneur by his motives rather than by the results he produces. And in Houdini’s case, that result was the astonishment and entertainment of hundreds of thousands of people.

Houdini’s fame—what we would now call his “brand”—has outlived him. It was reinforced decades after his death in a 1953 film starring another son of Hungarian Jews, Tony Curtis (born Bernard Schwartz), for which Dunninger served as an adviser. That film scrupulously avoided any mention of Houdini’s Jewishness. Yet if his Jewish practice was thin, his attachments were not. Wherever he was, Houdini made a point of saying Kaddish on his father’s yahrzeit. He purchased a tract at the Machpelah Cemetery in Queens, where he had his mother and father buried, with room for him and some of his siblings (though not for Bess, since she was not Jewish).

Although Ehrich and Bess Weiss had no children to say Kaddish for them, Houdini has had many cultural descendants. Today, the largest collection of Houdini paraphernalia is owned by David Copperfield, the most commercially successful contemporary escape artist, and is headquartered in Las Vegas. There is the House of Houdini in Budapest, run by another Jewish escape artist, David Merlini. One evening, as I took a break from reading Begley’s well-paced biography, I turned on an Israeli cable channel, and there on the television screen was an Israeli escape artist, Hezi Dean, performing a dramatic escape from the Water Torture Cell, with a poster of Houdini in the background. Perhaps the last chapter in the curious saga of Jews, magic, and escape artistry has not been written.

Begley’s account of this curious Jewish life won’t leave his readers improved or morally uplifted, but it will leave them entertained and astonished, and that’s a kind of magic of its own.

Suggested Reading

Jews on the Loose

If fame is when everyone understands it is you when only your first name is mentioned, Groucho (Marx) certainly qualifies.

History of Mel Brooks: Both Parts

On-screen, Mel Brooks was hysterically funny. Off-screen, he could quickly shift to morose or mean.

Super Stan

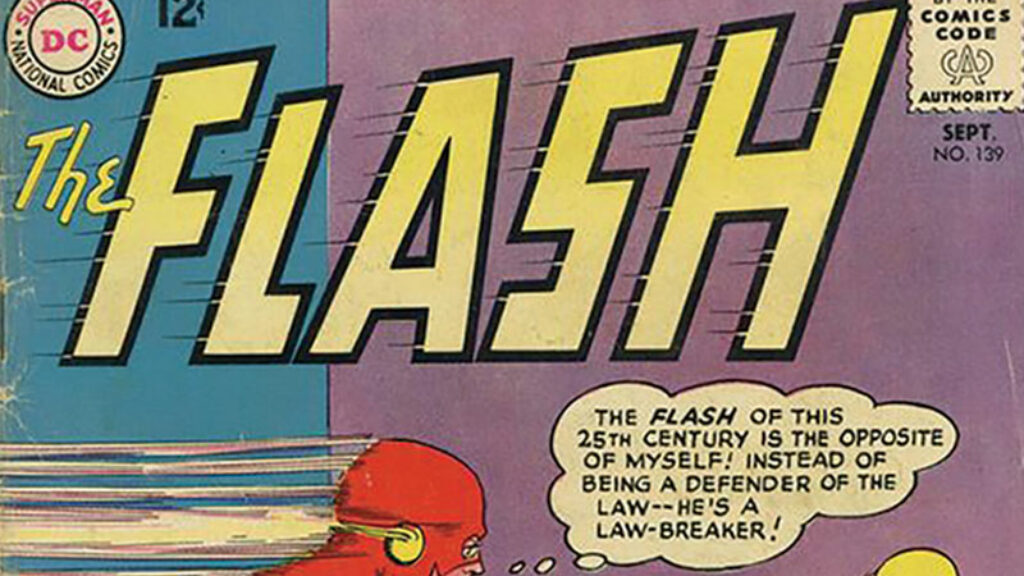

Even in comparison with so many other contributions to American popular culture and entertainment, comic books are an especially Jewish story.

Nothing but Blue Skies

Irving Berlin was generating Tin Pan Alley hits before Ronald Reagan was born and was still writing lyrics when the elderly Reagan occupied the White House.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In