Super Stan

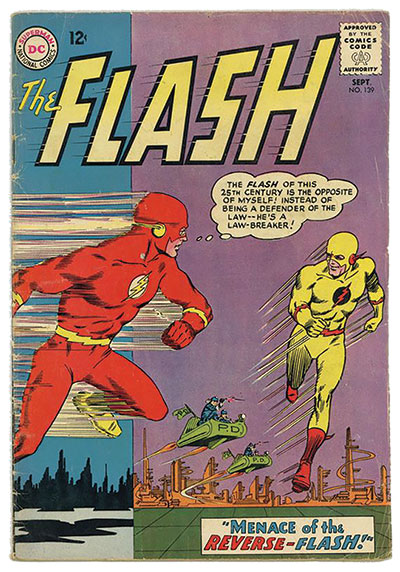

Superheroes have struck deep roots in American culture, and they often spring from deep places in the psyches of their creators. Consider Jerry Siegel, whose father died in 1932 after being attacked by a criminal in his own Cleveland clothing store. A few years later, in collaboration with Joe Shuster, Siegel would create Superman, the icon of American icons and a man of steel who would be impervious to such assaults. I can relate to Siegel’s impulse. My father was murdered when I was three. As a boy, my favorite comic-book character was the Flash, not because he was, as per his tagline, “the fastest man alive,” but rather because of his ability to “vibrate his molecules” (a feat of comic-book science) and pass through solid matter. To be able to move untouchable through a dangerous world seemed like a good idea to me.

It can be hard to assign authorship, though, in the case of the highly collaborative comic-book industry, whose publishers sought to maximize profits and minimize creative rights. Yet if we were to identify the person who has had the most impact on superhero comics, it would have to be Stan Lee, the subject of Liel Leibovitz’s passionate new entry in Yale’s Jewish Lives series. Lee, working with artists and cocreators such as Jack Kirby, created the heroes of the Marvel pantheon that now bestrides the entertainment world.

Lee’s parents were poor Jewish immigrants. His father, a garment cutter, was wiped out in the Depression, and his son, then Stanley Lieber, became a hustler, determined to rise above the financial insecurity of his childhood. Though Lee was an avid reader, college was out of the question. As a teenager, Lee worked as a gofer at Atlas Comics, run by his relative Marvin Goodman. In World War II Lee wrote informational plays about army payroll regulations at a desk next to William Saroyan’s (the small team also included cartoonist Charles Addams, director Frank Capra, and author Theodor Geisel, of Dr. Seuss fame). Other than that hiatus, Lee stuck with the industry even during the 1950s, when Fredric Wertham’s moral crusade against comic books instigated congressional hearings and industry layoffs.

Even in comparison with so many other contributions to American popular culture and entertainment, comic books are an especially Jewish story. In addition to Superman’s creators, Bob Kane (born Kahn) created Batman, and Jack Kirby (Jacob Kurtzberg) and Joe (Hymie) Simon invented Captain America. The comic-book format itself was pioneered by promotional publisher Maxwell Gaines (Ginzberg). Kane and Lee attended the same high school as the great comic-book artist and early graphic novelist Will Eisner. Even René Goscinny, the cocreator of France’s most successful comic-book hero, Astérix, spent the late 1940s sharing a tiny New York City artist studio with MAD magazine creator and fellow Jew Harvey Kurtzman. All this reflected an immense midcentury unleashing of Jewish American creativity—as well as the refusal of many advertising firms to hire Jews.

But Lee took the medium in a new direction. By the end of the 1950s, the threat posed by Fredric Wertham and his supporters had been neutralized by industry self-censorship and a shift away from horror and crime comics to superhero titles. DC Comics especially enjoyed a renaissance in what is now referred to as the “Silver Age” of American comics. Its most popular title was the Justice League of America, which united Superman, Flash, Wonder Woman, Batman, and other DC heroes. Over at Atlas Comics, Lee’s boss Marvin Goodman wanted to copy its success and ordered his team to come up with a Justice League knockoff. Lee and Jack Kirby gave their boss something different. Rather than assembling another roster of lantern-jawed supermen, they invented a squabbling family of flawed human beings who happened to have been granted exceptional powers.

The result, the Fantastic Four—Mister Fantastic, Invisible Woman, Human Torch, and the Thing—was an instant success. And over the next few years, Lee, often in collaboration with Kirby, developed a line of other all-too-human superhumans: Spider-Man, the Hulk, the X-Men, Thor, Iron Man, the Avengers, Black Panther, and more. By the mid-1960s, Lee’s division of Goodman’s publishing house, Marvel Comics, had overtaken DC Comics as the industry leader.

As Leibovitz explains, for all Lee’s corniness as a prose stylist, his heroes were self-reflective, morally complex city dwellers. Often unhappy, their powers caused as many problems as they solved. This sensibility reflected the ebullient pressure cooker of mid-20th-century anxieties and hopes that were simultaneously American, Jewish, and personal. Leibovitz further suggests, but does not quite fully explain, that Marvel’s morally engaged yet unredemptive vision was a vital Jewish end-run around the longstanding Protestant cultural stalemate between fundamentalist and progressive visions of salvation. I am more inclined to think of a favorite Yiddish saying of my grandmother that could stand as the motto of Marvel in contrast to DC: es geyt nit in di kleder (it doesn’t go in the clothes). In other words, it’s not about the costume.

Just as important as the vulnerably invulnerable heroes Lee (and, it must be emphasized, Kirby and Lee’s other cocreators) gave us was the narrative world they inhabited. In his classic 1962 essay, “The Myth of Superman,” Umberto Eco noted how DC Comics tended to present its heroes at the beginning of each new issue unchanged by anything that had happened previously. Their stories were myths, cyclical reenactments that did not allow for the register of time. As Leibovitz puts it, they were “perpetual motion machines that had only one, simple setting: swoop down, save day, repeat, repeat.” In contrast to what Eco saw in DC comic books, Marvel’s heroes inhabited a single soap opera universe in which characters brought their problems and failures from one issue to the next, and even across different titles. “All of them,” scholar Charles Hatfield writes, “heroes and villains, belonged to a great, sprawling, superhuman family whose interweaving, often violent relationships were tangled and confusing, but also compelling.” Lee, who always regretted not being able to go to college, had created a kind of campus populated with superheroes.

While DC would move closer to the Marvel model, this different sense of time and storytelling would have far-reaching consequences for the fortunes of both pantheons in our own day. DC is both blessed and cursed with a collection of icons—Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and company—but has struggled to bridge the narrative gap between its lofty superbeings and the world of human sorrow. In recent decades, the solution of too many writers (and filmmakers) to this problem has been the easy mode of adolescent sacrilege, mocking or subverting the idols of the DC pantheon. Only a very few writers, above all Alan Moore in his gothic reimagining of DC’s horror comic Swamp Thing, have done exciting work in this vein. DC’s recent success with Wonder Woman may be due not only to the preternatural winsomeness of actress Gal Gadot but also because the new Wonder Woman movies tell the story of an immortal figure struggling to engage human history, allowing DC to tackle its basic conundrum head-on.

The brilliance of Marvel film producer Kevin Feige, on the other hand, was to realize that Lee and company (and by “company” I include not only writer-illustrators Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and colleagues but next-generation Marvel creatives like writer-artist Jim Starlin) had already bequeathed all the stories, loss, death, change, and derring-do that he would ever need. As president of production at Marvel Studios since 2007, Feige adopted Lee’s storytelling approach on a billion-dollar scale. Rather than think in terms of mere sequels, let alone stand-alone films, Feige spearheaded the creation of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU)—an interconnected, self-aware set of ongoing melodramas in which heroes turn on each other, mature, grieve, and even die in the line of duty. The MCU now claims the highest-grossing movie of all time (Avengers: Endgame, box office currently at three billion dollars), and nine MCU movies are in the top 25 earners.

Leibovitz treads lightly on the less pleasant stages in Marvel’s long road to the MCU box office. The recriminations between Lee and Kirby about authorial credit, Marvel’s near bankruptcies, poor licensing decisions, and the checkered history of early television and film adaptations are only touched on. Sean Howe’s Marvel Comics: The Untold Story places Lee in a broader chronicle about the interplay between art and business. Similarly, the travails of Lee’s last years before his death in 2018 are summarized tersely. While moviegoers enjoyed the nonagenarian Lee’s regular cameos in the MCU films, Lee, especially after the death of his wife of 70 years, became a victim of financial abuse by business partners, one of whom even stole vials of his blood to stamp his signature on Rise of the Black Panther #1 and other collectible comic books. Leibovitz—in more of a DC than Marvel spirit—tends to set such unsavory episodes aside and celebrate Lee’s achievements.

Like many contributors to American popular culture, Stan Lee’s Jewishness is omnipresent but diffuse; it tends to evaporate if focused on too closely. Although his family attended synagogue and Lee had a bar mitzvah ceremony, Leibovitz admits we should be wary about projecting onto him “any rabbinic-like familiarity with or passion for Judaism’s texts or traditions.” Nevertheless, he tries “to understand Lee’s creations by planting them in a Jewish context and seeing whether they fit.” The result is a series of daring homilies.

Some of these drashot are more plausible than others. I enjoyed Leibovitz’s application to Spider-Man of Rav Soloveitchik’s distinction between the Bible’s two paradigmatic human stances—the striving for mastery, on the one hand, and the experience of spiritual humility, on the other—which really does fit the teenage web-slinger. I’m less convinced when he suggests that the Thing and Mr. Fantastic are like Hillel and Shammai because they “routinely offer up divergent ways of looking at the world.” Nor is it particularly interesting to characterize the physically strong but ugly Thing as “a golem,” since that silent monster owes at least as much to non-Jewish, often antisemitic writers as to Jewish tradition. (And surely no golem ever bellowed “It’s clobberin’ time!”) Leibovitz’s attempt to link Mr. Fantastic to the dybbuk story because he is “possessed by . . . vanity and impudence” seems, like that elastic superhero, a bit of a stretch.

Leibovitz himself cites a Marvel comic from 2002 in which the Jewish identity of Ben Grimm, a.k.a. the Thing, is finally taken up directly. In this issue, not penned by Lee, Grimm returns after many years to his old neighborhood on Yom Kippur and comes to the aid of an impoverished Jewish pawnbroker, who gives him a Magen David necklace after the superhero recites the Shema. Saying the Shema once every few decades is the most Judaism of any explicit sort you’re likely to find in the Marvel universe. Lee’s Jewish spirit is there, but it’s mostly a matter of humane humor, tempered experimentalism, and uneasy hopefulness.

And how fares this spirit today, a year and a half since the passing of the great man of Marvel comics? It is a question as to whether Lee’s patriotic, broadly liberal, Kennedy-era sensibility can withstand the demands of today’s cancel culture, Hollywood political conformity, and woke capitalism. Having built his movie monument to Lee’s vision, Feige may not at this point mind letting the woke left live off some of the capital—consider actress Brie Larson’s petty attack on male fans while she was promoting last year’s Captain Marvel film—but eventually the corrosive effects—including boredom—will become more noticeable. These heirs of Fredric Wertham’s censorious puritanism will suck the life out of popular culture as readily as Lee and Kirby’s archvillain Galactus sucks the life out of planets.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

What . . . Him Worry?

How did Abraham Jaffee, raised in the shtetl of Zarasai, became one of MAD magazine's most prolific and recognizable cartoonists?

Meanwhile, on a Quiet Street in Cleveland

Two Jewish kids from Cleveland created Superman. Why does the Man of Steel still fascinate us?

What They Talk About When They Talk About Golems

On golems and global conspiracy theories.

Brave New Golems

As monsters go, golems are pretty boring. Mute, crudely fashioned household servants and protectors, in essence they’re not much different from the brooms in the “Sorcerer’s Apprentice” story.

Scott Johnson

Wonderful essay.