An Israelite with Egyptian Principles

Judah Philip Benjamin could have been the first Jew to serve on the United States Supreme Court, but in 1852 he made clear his lack of interest in the honor that President Millard Fillmore was prepared to offer him. This was not because he was wary of holding high office; he became a senator from Louisiana in 1853. Benjamin was not, however, as James Traub maintains, “the first, or second, Jew to go to Congress.” Even if one does not count David Yulee of Florida as a Jew (and Traub does count him), one can’t overlook Lewis Charles Levin of Philadelphia, who served in Congress from 1845 to 1851, and Emanuel Hart from New York, who was elected in 1850. Moreover, Philip Phillips of Alabama entered Congress on March 4, 1853, the same day that Benjamin did. That means Benjamin is tied for fourth with Phillips.

Wherever he stands on the list of Jewish members of Congress, however, Benjamin was indisputably the first American Jew to serve in a president’s cabinet. Unfortunately, that president was Jefferson Davis. Benjamin served as the attorney general, secretary of war, and, from 1862 to 1865, as secretary of state of the Confederacy. He was a leading figure in the Confederate government from start to finish. Known during the Civil War as the “brains of the Confederacy,” a nickname he deserved (although it was not particularly high praise), Benjamin was Davis’s most loyal supporter in his cabinet—until he chose to flee to England rather than remain in the South as it was collapsing.

Always identified or marked as “the Jew” by friends and foes alike, there is little about Benjamin’s career or life that was Jewish. Born in 1811 into a Sephardi family in Saint Croix, Benjamin grew up in Charleston, South Carolina, where he attended Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim, an Orthodox Sephardi synagogue that later became America’s first Reform congregation. Traub anachronistically calls it a “temple”; more inexplicably, it is also how he describes Bevis Marks, the oldest synagogue in London and one that remains Orthodox.

Benjamin would eventually live in five other cities with substantial Jewish communities (New Orleans, Washington, Richmond, London, and Paris), but he never affiliated with any of them. He probably never entered a synagogue after the age of sixteen, and, as Traub notes, despite his “erudition,” Benjamin “knew little of Jewish law or scripture.”

The great unanswered question is why he

remained Jewish at all. Traub speculates that the combination of his name and

his “dark curls and dark skin” would have continued to mark him as a Jew, even

if he had converted. Perhaps, but we should also note that in both Charleston and

New Orleans, the main fault lines of social acceptance were racial, not

religious. Both cities, unlike Richmond, had Catholic communities and prominent

residents who traced their families to France, Spain, and other places on the

Continent. Benjamin’s Sephardi heritage did not seem to be an impediment to

success. He may even have seen it as an advantage, making him slightly exotic

in New Orleans, a city in which the exotic has always been prized. Moreover,

Jews were seen as scholarly—the people of the book—and Benjamin prospered as

“the smart

Jewish lawyer.”

Benjamin was certainly frighteningly smart. He entered Yale College as a precocious fourteen-year-old, subsidized by a Jewish leader in Charleston. Although he was a poor Jewish kid swimming in a Protestant sea, the star student ingratiated himself with his older, wealthier, sophisticated, and socially connected classmates. But two and a half years later, he was expelled for “ungentlemanly conduct.” Benjamin always claimed he was forced to leave because of a small unpaid bill to the college, though that seems unlikely. The real story may have involved petty theft from his classmates, perhaps to cover gambling debts.

In 1827, the sixteen-year-old Benjamin arrived in New Orleans, a large, bustling port city. Five years later, he was admitted to the bar, had mastered French, and married Natalie St. Martin, the strikingly beautiful sixteen-year-old daughter of a well-to-do planter. It would be an unhappy union, marked by Natalie’s not-so-discreet liaisons with other men. After their daughter was born, Natalie abandoned Benjamin and moved to Paris. He tried to visit them once a year.

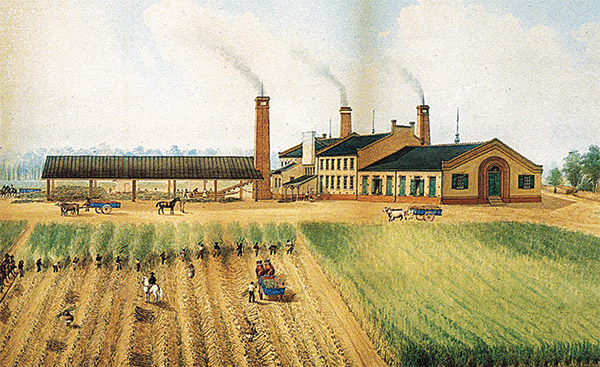

Brilliant and charming, with an enormous capacity for very hard work, Benjamin soon became one of the leading attorneys in the state. His Digest of the Reported Decisions of the Superior Court of the Late Territory of Orleans and of the Supreme Court of the State of Louisiana (1834) quickly became an indispensable treatise for local lawyers. He was the go-to man for insurance companies, shippers, and planters. In the 1840s, he bought a sugar plantation, Bellechasse, and became the owner of some 140 slaves, more than any other Jew in the country.

Owning a large plantation turned Benjamin into a Southern gentleman, increased his wealth, and reinforced his lifelong commitment to slavery. That he embraced the South’s “peculiar institution” enthusiastically has created a problem for almost all of his biographers. Traub, for his part, seems to search for evidence that Benjamin was not really committed to slavery. He notes, for instance, that in defending an insurance company for the loss of slaves due to a shipboard revolt, Benjamin described the revolt as a natural one because slavery “is against the law of nature.” Traub admits that Benjamin was cynically deploying this argument to win his case, but he hedges a little, suggesting it may illustrate his discomfort with slavery. Trying to put his subject in a better light, he notes “the inner recesses of Benjamin’s soul remain a mystery.” He states of Benjamin that “only rarely would he insist on the sub-human nature of black people that served as moral justification for slavery.” But most white slave owners considered blacks fully human. They baptized them, took them to church, sometimes even paid ministers to marry them. Many, including Jefferson Davis, had children with them. The defense of slavery was based on arguments that blacks were “inferior” to whites and the claim that the Bible sanctioned it because they were descendants of Noah’s cursed grandson Canaan, not because they were less than human.

Indeed, throughout his life, Benjamin defended slavery in his writings, arguments in court, speeches in the Senate, and as a leading official of the Confederacy. He bought and sold people without qualms. He was a leader and founder of a political regime, as Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens put it, whose “corner-stone rests . . . upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition.” Benjamin agreed with all of this.

Traub writes that in the slave markets of New Orleans, “Benjamin could have come to know something . . . that perhaps he would rather not know: that children were torn from the arms of their mothers, and husbands taken from their wives.” But Benjamin was surrounded by slavery in Charleston. He saw it every day. If he had moral qualms about slavery, he could have moved north at age sixteen, when he left Yale, not further south. Many Southerners (most famously the family of Abraham Lincoln) did this. Or he might have left the South in 1861, like Rabbi David Einhorn, who had publicly denounced slavery, or officially sided with the United States in 1861 like the slaveholding Virginian generals Winfield Scott and George H. Thomas (later called the Rock of Chickamauga) and Senator Andrew Johnson. He did none of these things because he evidently liked slavery, believed in it, profited from it, and defended it, as Traub points out, even after the war, when he was in England. In this way, Benjamin was little different than many, perhaps most, Southern Jews, who embraced this society and participated in it alongside their white Christian neighbors.

In the Senate, Benjamin vigorously defended slavery. He turned down a seat on the US Supreme Court in part because he loved the verbal combat with antislavery northerners, which made him a hero of the South. He was Jefferson Davis’s most loyal supporter because, as Traub writes, “like Davis, he felt absolutely certain of the South’s moral as of its martial superiority.” He condemned Northern mistreatment of Southerners but supported Davis’s use of martial law across the South, the total suppression of free speech in the South, and summary executions for civilians accused of disloyalty. He had no problem when the Confederate army murdered surrendering black US troops or kidnapped free blacks in the North and dragged them South as slaves. Like so many other Southern leaders, Benjamin had no use for international law, civil liberties, or the rule of law if they got in the way of supporting slavery and white supremacy. “In the midst of a debate over the extension of slavery,” Traub tells us, “Senator Benjamin Wade of Ohio . . . unforgettably captured Benjamin as one of the ‘Israelites with Egyptian principles.’” Wade was clearly correct.

Despite his incredible, almost fawning, loyalty to Jefferson Davis, Benjamin was a realist, and his ultimate loyalty was always to himself. When the slaveocracy’s experiment in high treason was clearly failing, he secretly shipped cotton to England and planned his escape. He was the only Confederate cabinet member to evade capture. Benjamin made his way first to the Caribbean and then to England. In London, he remade himself as a hugely successful barrister and legal scholar. His last treatise, The Law of Sale of Personal Property; With References to the American Decisions, and to the French Code and Civil Law (1868)—known then and now as “Benjamin on Sales”—is, amazingly, still in print.

After the Civil War, many former Confederates would level antisemitic attacks at Benjamin for abandoning his country at the end of the war, shipping assets to England during the war, and making off for London with Confederate gold. In truth, he had already abandoned his country four years earlier, in 1861.

Traub’s biography is lively, well written, and engaging. There are superb vignettes of political leaders and vivid descriptions of Benjamin’s oratorical and forensic skills. Unfortunately, it is also often inaccurate. Traub tells us, for instance, that in 1828, when Benjamin moved to New Orleans, the Mississippi River was “America’s western boundary,” and New Orleans was “a remote outpost of a nation still gathered along the Eastern Seaboard.” This would have surprised everyone living in New Orleans, which is west of the Mississippi, not to speak of all of the other Americans living west of the Mississippi in most of the rest of Louisiana, Saint Louis and the rest of Missouri, and what is today Arkansas, Iowa, and Minnesota. Mapmakers at the time showed the United States extending as far west as the Pacific Ocean. Nor was New Orleans a “remote outpost”—it was the fifth-largest city in the nation.

Traub asserts that General Henry Wise (who reported to Secretary of War Benjamin) was a former US senator from Virginia, implying that they had been senatorial colleagues, but Wise never served in the Senate. He served in the House of Representatives but left that office a decade before Benjamin arrived in the Senate. He tells us that George Mason (the grandfather of the Confederate diplomat James Mason) had been a “hero of the Continental Congress,” but Mason never served in the Congress; he was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. He asserts that in the Dred Scott case, the Supreme Court should have “confirmed the constitutionality of the fugitive slave laws.” Although Dred Scott did find that slaves traveling to free states remained enslaved, Dred Scott was never a fugitive slave, the case was not about the fugitive slave laws, and none of the lawyers or justices involved thought it was.

Despite the many such errors, Traub has written a vivid portrait of Judah Benjamin, who led an utterly fascinating (and marginally Jewish) life. It is not always pretty, but history often isn’t.

Suggested Reading

Inventing American Judaism

Unlike the Jews of Venice, whose charter was anxiously renegotiated every decade or so, American Jews participated in civic life, confidently building themselves a future.

Lincoln and the Jews

Lincoln encountered a surprising number of Jews in his life. Throughout, he seems to have treated them with the benevolence and absence of prejudice one would expect from the Great Emancipator.

Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh Walk into a Bar: Passover in the Union Army

Yankee ingenuity at Passover: how one regiment made a Seder in the midst of the Civil War.

Samson Raphael Hirsch’s Attack on Liberal Christian Bigotry and American Slavery

In 1841, Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch leapt into a raging debate between liberal and orthodox Protestants, declaring, “It is high time for the non-Jewish thinker to set aside convenient pre-judgements and to begin to construct Christendom without having to destroy Judaism.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In