Some Kind of Genius

“Christ, I’m tired,” Ben Hecht grumbled to his wife Rose in 1931. Stuck in Hollywood, Hecht was writing Scarface and complaining mightily. “Oh how tired I am!” he continued, gathering strength with every groan. “Aches, neck, back, eyes, heart—oh so tired.”

This is the sound of a man enjoying his misery; a master at the Jewish art of recreational kvetching. With Hecht, the line between pain and pleasure was vanishingly thin. In Hollywood, he wrote seemingly effortless dialogue until he collapsed (“I love a good honest pain, as you know”). Blurred lines abounded in Hecht’s life. When writing The Front Page, his great collaboration with Charles MacArthur, he set out to skewer journalism but produced a love letter. “Our contempt . . . was a bogus attitude,” he later confessed.

Little was ever straightforward with Hecht, the playwright, journalist, and screenwriter-savant of Hollywood’s first golden era. Did he single-handedly rescue Gone with the Wind? Could he, or anyone else, have written Scarface in 11 days? Legends aside, there was something inscrutable about the man. “Hecht is a rather difficult man to pin down,” Saul Bellow once wrote. The poet Doug Fetherling, who wrote a shrewd 1977 appreciation of Hecht, admitted that “no one is quite certain who Hecht was.”

Hecht’s life should come with a warning label: Biographer, beware. A trickster, a prankster, a cool Wildean ironist, he was always a fast-moving target. When reporters quizzed him, they got the runaround: evasion, omission, deflection. “I have always had a distaste for telling the truth about myself,” he confided to H. L. Mencken. Indeed, mischief—getting away with things—supplied life’s greatest pleasure for Hecht, along with writing rapidly and well. No wonder so many Hechtian legends survive, with some dust on them, 55 years after his death. In common memory, he is still the speed writer, the one-draft wonder, the Hollywood-bashing iconoclast, the swashbuckling social critic.

Inevitably, the legend takes a beating under Adina Hoffman’s scrutiny. In her compact new biography, she attempts to recover Hecht from legend, refraction, obfuscation. It’s a valiant attempt, but in the end, she falls victim to Hecht’s expertly set traps. In a way, this book is like its subject: charming, never dull, and something less than trustworthy.

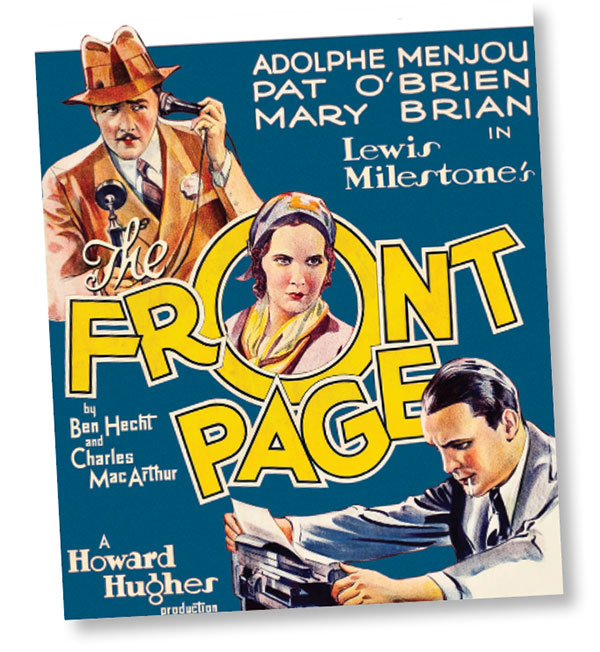

Hoffman begins confidently, asserting Hecht’s status as a towering Hollywood scriptwriter. Working with great directors—Hitchcock, Hawks, Preminger—Hecht penned a half-dozen bona fide classics. The Front Page, based on Hecht’s antic newspaper play, invented the screwball comedy. Underworld, the ur-gangster drama, paved the way for later bloodbaths. No Hecht, no Goodfellas—and maybe no Sopranos, either. Hecht’s films “helped create Hollywood as we know it,” Hoffman writes, but beyond that, they’re simply great fun—“among the most delightful ever made.”

Then the chronological march forward begins, and things get shaky. Hoffman renders Hecht’s early years in broad, colorful strokes, jumping from New York City (“the ghetto,” Hecht boasted) to Racine, Wisconsin. Young Hecht is carefree and mischievous, a talented thief, marksman, and saboteur of railroad tracks. A young Lothario, he scores with Racine’s willing daughters, whose irate fathers chase him over fences. For Hecht, youth is a carefree, uninterrupted idyll, with the added bonus of benign, encouraging parents.

So far, this resembles no childhood—certainly no writer’s childhood—that ever existed; yet it extends long past puberty. Hecht goes off to college, drops out, and lands on his feet in Chicago. With his uncle’s help, he inveigles a newspaper job at the Chicago Daily Journal. Soon, he is hoodwinking editors, who print his fabulous stories about river pirates and earthquakes. Somehow, he parlays these pranks into a “star” position at the paper. When Hecht leaves Chicago, it’s front-page news; a rival paper declares it a tragedy: flags lowered to half-staff!

How much of this actually happened? Some, perhaps. Serious Hecht fans will recognize these fables—they’re cribbed from Hecht’s highly unreliable memoirs. Some poking around in Hecht’s archives reveals more pedestrian truths. The newspaper job? In one account, Hecht’s mother got it for him; in another, he used a chain of connections. As for college, there’s no proof Hecht came anywhere near the University of Wisconsin campus. A letter from a university staffer, recently deposited in the Hecht archives, exposes the fiction. Hecht wasn’t a “star reporter” for the Chicago Daily Journal, nor did he cover “crime and corruption in their most sensational form.” For the most part, Hecht was an ordinary court reporter, covering unsexy stories in Chicago’s byzantine court system. Most of his articles were brief and unbylined.

All kinds of dubious stories are foisted on the reader in these chapters. Hecht never hoaxed his editors; that story was itself a hoax. He almost certainly never lived in “the city’s most notorious bordello.” He lived with, or across from, his doting parents. In Hoffman’s telling, the writer Sherwood Anderson “was enraged” over Hecht’s portrait of him in a novel. He wasn’t. In letters to friends, Anderson praised Hecht’s novel, saying nothing about his cameo. When Hecht left Chicago, a flattering story appeared by his friend Ashton Stevens, but it was a squib, buried on page nine, not “front-page” news. And on and on.

(The Jabotinsky Institute and PikiWiki.)

What’s curious about all this is that Hoffman seems to know better. In wiser moments, she notes how slippery Hecht can be: Hecht’s stories “have the gusty air of legend”; some sound like “sheer make-believe”; others like “vivid hyperbole.” Yet she ignores her own warnings. At some point she seems to have made the fateful decision simply to repeat Hecht’s gusty legends without any disclaimers. The result is a steady stream of Hechtian whoppers. Ben Hecht: Fighting Words, Moving Pictures is briskly paced, stylishly written, and clearly the product of serious effort and research. But that research is hopelessly interlaced with fiction and quasi fiction—Hecht’s wild, self-dramatizing lies. They slip in everywhere, insidiously. Even a doctored photograph of the ship Hecht funded to smuggle Holocaust survivors into Palestine sneaks in. As a crew member wrote to Hecht in the 1950s, “the photo . . . is a fake. The name SS BEN HECHT was never painted on the bow . . . We should advertise to the British Navy and Air Reconnaissance what we were doing?”

Ben Hecht was born in 1893, the favorite son of young, newly married Russian immigrants. His father, an ambitious but feckless clothing designer, and his sober, practical mother, managed two impressive feats: escaping dire poverty and imbuing their son with supreme confidence. From the start, Hecht recognized his own talents. In an early autobiographical novel, Hecht projected himself forward, into the bright future, and took stock of his achievements. There would be stories, novels, plays—“Triumph after triumph.”

In 1910, the budding littérateur landed in Chicago, where in some sense, his life began. Young Hecht—or “Bennie,” as he was affectionately known—discovered bohemia, where literature was the rage. “I worked in Chicago, but I lived, a little madly, between book covers,” he later wrote. He was fortunate to meet Sherwood Anderson, then unknown, unpublished, and somewhat illiterate, as Hecht later recalled. A close, rivalrous friendship soon developed, the older Anderson playing mentor and sage, a role Hecht accepted and resented in equal measure.

By 1918, Hecht’s star was indeed rising: he’d cracked Mencken’s magazine, The Smart Set, and the Best Short Stories anthology; at parties, he seemed to cast a spell over people. “There is only one intelligent man in the whole United States to talk to—Ben Hecht,” crowed Ezra Pound, an early admirer. Though these were, by most accounts, happy, secure years for Hecht, there were already signs of chaos and tumult. Hecht’s marriage to Marie Armstrong, a charming reporter at the Chicago Daily Journal, was turbulent from the start. They were marvelously ill matched: Hecht felt bored and trapped; Marie felt ignored and bullied. His Girl Friday it wasn’t. It didn’t help that journalism supplied the fun and excitement Hecht craved. By this point, he was flourishing, producing stories rich with humor and storytelling and vivid characters.

Journalism occupied Hecht’s days, but daily deadlines didn’t exhaust his astounding energies. Nothing did, apparently—Hecht worked with restless, manic energy. “I feared idleness as some men fear a contagious disease,” he recalled. “Without a task to do, I became convinced I would expire of ennui.” A second compulsion was to entertain—to always impress and dazzle. “I need an audience, even in my sleep,” the hero of an early, unpublished novel says. “It is difficult to be amusing, always,” another character sighs.

Who, though, was behind the performance? Many young writers construct a self out of books, but few have done so as avidly and publicly as Hecht. In his twenties, Hecht was variously a cynic, a Decadent, a dandy, a poète maudit. (“There were always a surprising number of me’s in operation,” he later recalled.) It seemed Hecht borrowed promiscuously, but, in fact, he chose his influences carefully. Nietzsche’s gospel of superiority and boldness suited him well. So did H. L. Mencken’s swashbuckling style and amused contempt for phoniness and cant. By his late twenties, Hecht was phenomenally well read, and, it seems, equally well armored with cynicism, snobbery, and humor—the young male writer’s classic arsenal.

A census of Hecht’s poses in the 1920s reveals one striking absence: There was no Jewish version of Hecht. Of course, few people flaunted their Jewishness back then. Even so, Hecht’s “passing” seems extreme. Years later, in crafting his life story, Hecht insisted he had no Jewish past to speak of. “I had not been a Jew in Chicago and I continued in New York not to be one,” he wrote. His life was one of “pleasant Jewish anesthesia,” untouched by anti-Semitism. “I repeat,” he wrote, “all my activities, all my writing and living had been since my childhood as unJewish as the doings of a Martian.”

The irony, of course, was that concealing his Jewishness only drew attention to it. To Ezra Pound, he was “Rabi Ben Hechtenberg”; to H. L. Mencken, a political radical with “Jew-like” proclivities. Even a benign figure like Carl Sandburg, the heartland poet, took notice, dubbing Hecht “a Jewish Huck Finn” who never stopped reading. Sandburg, a generous soul, wasn’t being hostile. Yet, at the same time, he refused to ignore the obvious, even if Hecht might have wished him to.

Hecht’s Jewishness—present everywhere, concealed everywhere—is, not surprisingly, a major theme of Hoffman’s biography. What makes a book Jewish, Philip Roth says, isn’t its subject, but that it won’t shut up.By that measure, Hecht’s loquacious novel Erik Dorn (1921) belongs in every Jewish library. The book was Hecht’s breakthrough: All at once, dozens of reviewers were singing his praises. A year later, Hecht’s remarkable journalism was collected in 1001 Afternoons in Chicago, a book so marvelously strange and cleverly written that it’s still assigned in journalism schools.

In quick succession came a Broadway play, several audacious novels, and the inevitable move to New York City. There, Hecht’s Jewish circle included Herman Mankiewicz, who would soon leave for Hollywood (“Eretz DeMille”). “Millions are to be grabbed out here and your only competition is idiots,” he famously wired Hecht—a note that surely appealed to Hecht’s snobbery, money-lust, and thirst for adventure all at once.

Lighting out for Hollywood proved the best and worst decision Hecht ever made. Until then, writing had been his vocation. Now it was a commercial enterprise. Hecht’s immediate success with Underworld ensured more lucrative assignments. It also primed him for an even bigger breakthrough: the grand success of The Front Page in 1928–1929. The play, a valentine to youth and irresponsibility set among Chicago’s crime reporters, made Hecht a genuine celebrity. Success begat success. As the country’s fortunes sank, Hecht’s continued to rise, with screenwriting offers pouring in. Suddenly flush, he acquired a kingly lifestyle, with an entourage of servants, chauffeurs, and secretaries attending to him. Hollywood needed Hecht, and Hecht needed Hollywood’s huge paychecks. Each new contract from Samuel Goldwyn and David Selznick was an offer he couldn’t refuse. For the next decade, he veered between passion projects—novels, stories, and plays of varying quality—and well-paid “hackwork” (as he called it): classic films like Nothing Sacred, Viva Villa!, and Gunga Din.

That might have been it—a hectic life shuttling between coasts and careers—had German fascism not seized Hecht’s attention. In 1939, he underwent a startling public transformation: Gone, suddenly, was the preening Hollywood showman. Gone, too, was the arch individualist. In their place roared an earnest, committed activist, proudly declaring “My Tribe Is Called Israel” and exhorting American Jews—especially his wealthy, secular brethren—to express Jewish pride and vent Jewish outrage.

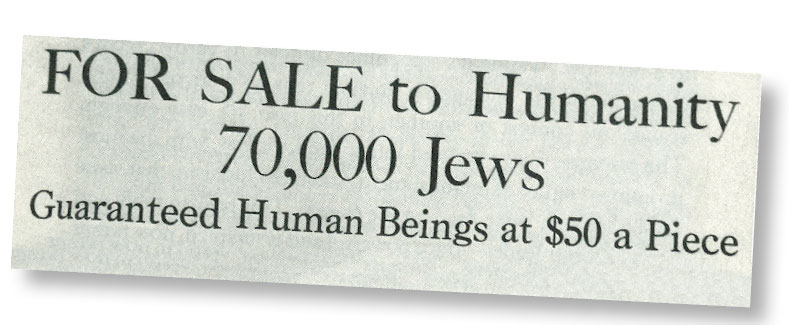

That was only the beginning. In 1941, Hecht “bumped into history” when Peter Bergson, a passionate activist from British Mandate Palestine (there he was Hillel Kook, Rav Kook’s nephew), recruited Hecht into his American operation. Soon Hecht was writing ferocious advertisements that mixed humor with moral outrage. “FOR SALE to Humanity: 70,000 Jews,” one ad proclaimed during the Holocaust, when rescue still seemed possible. “Guaranteed Human Beings at $50 a Piece.” In his most incendiary ad, Hecht saluted “My Brave Friends” of the Irgun underground. “The Jews of America,” he added, “make a little holiday in their hearts” after each successful attack. That bit of poetry—10 soft syllables, as hummable as a nursery rhyme—detonated across Jewish America.

This chapter of Hecht’s life makes for exciting, if confounding, reading. For seven years, he wrote speeches, mobilized friends (who marveled at his newfound passion), and defended the Bergson campaigns, which faced intense resistance from mainstream Jewish organizations.

In 1946, his Zionist pageant A Flag Is Born raised enough money to purchase a ship, dubbed the SS Ben Hecht, which sailed incognito toward Palestine with 600 DPs on board. The Bergson group’s courage, boldness, and integrity seemed to bring out the best in Hecht. Had they indeed awakened his Jewish self? Or did Hecht have a secret Jewish life long before he met Peter Bergson?

Here, Hoffman’s research is illuminating. Her book’s main revelation is that Jewish issues had always preoccupied Hecht. Slowly, a portrait emerges: Hecht wasn’t a believer, wouldn’t have recognized the inside of a shul, and didn’t keep kosher; yet he felt profoundly Jewish. Sifting through archives, Hoffman locates Hecht’s Yiddish-inflected poetry in a self-published magazine. She finds plans for a “peculiarly Jewish novel” (Hecht’s words) to be published in two volumes. The teenage Hecht, asked why he concealed his Jewishness, replied that he “did not wish to boast,” a detail quarried from an obscure memoir.

A conventional Jewish upbringing was the foundation for Hecht’s Jewish attachments. As a boy, he suffered through Hebrew lessons, the misery ending with his confirmation. In late 1925, Hecht surprised his friends by moving to the Henry Street settlement, near his childhood home. The sound of spoken Yiddish, the comforting density of Jewish communal life on that bustling shtetl block, called out to him. Even Hecht’s 1931 novel A Jew in Love, with its noxious Jewish stereotypes, suggests something more than indifference. Hoffman finds the book “perverse” but also revealing, proof of Hecht’s “deeply divided sense of Jewish self.”

So much for Hecht’s claims to a belated Jewish awakening. Hoffman laughs: “He’d been a Jew from the get-go.” Taking Hecht’s testimony “with a grain of kosher salt” makes perfect sense, here and elsewhere. What about Hollywood, then? “While he claimed loudly to loathe the movies and all they stood for, he also quietly adored them.” That might be stretching it, but at least Hoffman is reading against the grain. Pondering Hecht’s 1937 play To Quito and Back, she senses a writer at sea, craving a purpose. She’s certainly on to something, yet her fast-paced narrative speeds ahead, with Hechtian velocity, never looking back.

Hoffman solves half the mystery of Hecht’s Jewish rebirth and conversion to militant Zionism. Still, one senses a larger, more complicated story unfolding. In 1935, his mother died, a devastating loss that haunted him for decades. In the aftermath, he embarked on a (predictable) affair, sneaking off to Quito, Ecuador, with a young socialite. He returned in 1937, his marriage to Rose miraculously intact, and promptly suffered a setback: the failure of his comeback play. The New York Times called To Quito and Back “a sham battle of words and fine phrases.”

Turbulent though that period was, it seems continuous, in some ways, with Hecht’s earlier life. To read Hecht’s letters from the 1920s is to behold a troubled soul, who, when he’s not playing the Superior Man, is profoundly stuck. He’s tired of constantly performing and feels trapped inside his many masks. “You have not a pose that is more important than your soul,” he writes plaintively to Rose. “I have. Artists usually have.” Moreover, he’s split down the middle: “A rueful truth—the contradictory desires of humans who want always to be free and at the same time to be servants of something,” he later wrote. Hecht gave that dilemma to his fictional stand-ins, tortured writers all. They fear failure, these anxious, well-defended young men, but even more than that, they fear hollowness and solipsism.

Generally, one shouldn’t conflate an author and his creations. But with Hecht, you might as well. (“He is me,” Hecht wrote of one protagonist, a troubled Chicago journalist.) What’s clear from Hecht’s writing—but not terribly clear from Hoffman’s biography—is how greatly Hecht suffered, and how that suffering forged the person—and the Jew—he later became. By 1938, Hecht was a changed man. “Compassion came to me,” he later wrote, “compassion even for the stupid, the hypocritical and the ugly.” The old Nietzsche-Mencken mask fell away. When German mobs began targeting Jews, Hecht faced a stark choice: stoic silence or raucous hellraising. The first wasn’t his style at all. The second most definitely was.

Watching Hecht pinwheel through life, one senses the scale of Hoffman’s challenge. Biography imposes order on life’s chaos, but Hecht’s unruly life and vague, contradictory personality resist sense making. He could be frank or cunning, boisterous or shy, harsh or tender, and the exact balance of those qualities was never quite clear. Hoffman’s attempt to unravel “the puzzle that was Ben Hecht” yields few deep insights. At a loss, she labels him “perverse”—a biographer’s shrug.

That shrug alternates, here and there, with a wince. Hecht’s Holocaust pageant, We Will Never Die, was “relentlessly lugubrious” and “almost bullying in its high-minded mawkishness.” Hoffman groans at the “ad hominem assaults” in Hecht’s book on anti-Semitism, A Guide for the Bedevilled, finding it “exhausting.” These are strange reactions—surely “mawkishness” about the murder of European Jewry was a lesser crime in 1943 than silence.

Hoffman is harsher still on Hecht’s 1961 j’accuse, Perfidy, a contentious account of the Kastner affair, which divided Israel over the question of wartime collaboration. To Hoffman, it reads like a clumsy western: “a flamboyant rhetorical shoot ’em up.” Writing about Israel, a country he never visited, Hecht was “out of his element and less self-aware than ever.” Going further, Hoffman finds “something grotesque about the way he leaned back in his Nyack lawn chair and accused the likes of Weizmann and Ben-Gurion” of betrayal during the Holocaust. Perhaps, she suggests, Hecht wasn’t really angry, just acting out: “arguing for argument’s sake.” But any careful reader of the book (let alone Hecht’s notebooks) can see that Hecht was full of righteous fury. Turning away from Hecht’s anger, here and elsewhere, suggests a larger problem of biographical understanding.

All his life, Hecht was recklessly, noisily excessive, a man for whom too much was never enough. But for Hoffman, this too-muchness seems to be just a headache. Unlike Hecht’s movies, with their cleverness and pizzazz, Hecht’s novels teem with unseemly angers, vanities, doubts, insecurities. That, too, was a side of Hecht, though not a side Hoffman has much patience for. One pictures her slogging through novel after novel, wishing they were DVDs. Therein lies the problem. We never meet the author of these many vexing books. Hoffman all but ignores him, as if afraid to confront something messy, murky, and human. What spurred his attention seeking? Why was he so angry? Clearly, some of the answers must lie in Hecht’s childhood—his actual one, not the happy picaresque one Hoffman writes about.

The question looming over any account of Hecht’s life is whether he wasted it, artistically speaking. In the early 1920s, he was one of America’s most promising young novelists, “The whirlwind prose hope of Chicago,” as Ezra Pound put it. Then came Hollywood, several fortunes, and fame. What if Hecht hadn’t been lured westward—if, instead, he had channeled his considerable talent and energy into serious writing? Every author has a shelf of unwritten books. It’s tantalizing to imagine Hecht’s. Or perhaps not. “Hecht was among the very worst judges of his own talents,” Hoffman states confidently. “Screenwriting was Hecht’s calling, whether he liked it or not.” Well, yes—it’s hard to argue with success. Hecht’s movies are cherished; his best plays, especially The Front Page, stand as classics, but his novels and memoirs are largely forgotten.

Could those works be rediscovered today? Hecht was, in fact, a superlative writer, a graceful, confident prose stylist of A. J. Liebling’s or Joseph Mitchell’s caliber. He could do hardboiled, slapstick, lyrical—you name it. He was a master of the simple sentence that snaps at the end, inducing whiplash. “The Jews have the greatest unity in the world—as a target,” he once wrote. “They were for lucidity and laughter, when sober,” he wrote of his old newspaper chums. Writing on deadline, he produced gem after gem, some while risking his life in Berlin after World War I. “Yet the cabarets go on,” he wrote in one dispatch. “Whirling couples dance among the round-topped tables.” In addition to his appallingly good sentences, Hecht was one of those writers with an invisible stopwatch in his head telling him exactly when paragraphs should end.

Predictably, Hecht’s phenomenal speed and productivity tend to obscure everything else. Hoffman describes a force of nature: Hecht’s copy “splashed into his daily columns,” then it “erupted into a second novel”; later, it “gushed forth in impassioned geysers.” Some of that liquid was froth, it’s true, but some was extraordinary. 1001 Afternoons in Chicago, Hecht’s 1922 portrait of his adopted city, is a marvel, as close to time travel as journalism gets. Then there’s A Child of the Century, Hecht’s 1954 autobiography—really, Hecht’s song of himself, his greatest work.

These remarkable bookends—one a work of precocious brilliance, the other a capstone—contain Hecht’s multitudes, his various public selves. And yet, as Hecht’s letters reveal, the real drama of his life was internal: a person struggling against his darker, destructive impulses and trying to cultivate the gentler, more generous side of his character. It was the struggle to abandon the false selves he acquired in his twenties and become who he really was—or wanted to be, at any rate.

That story is largely lost on Hoffman, which is too bad, since there’s pathos in Hecht’s efforts to embrace his better angels. The final decades of his life—a reckless, courageous, in some ways tragic life—were filled with nostalgia, melancholy, and humble attempts at self-betterment. As quippy dialogue became passé, and Americans turned to television for distraction, Hecht’s screenwriting career wound down. He returned to his youth in several charming memoirs and embraced a kind of mindfulness.

“And what is joy?” Hecht wrote in his final years. “Existing out of myself. Responding to life with my senses and not my prejudices.Seeing others with amusement rather than fretting over being seen.” He began each morning with a prayer to the deity he never believed in, pleading for the strength not to harm anyone. That private battle didn’t make headlines, but it was as dramatic, and perhaps as heroic, as his more famous battles and triumphs.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Happy Is the People Who Knows the Blast

Rabbi Moshe Hayim Efrayim of Sudilkov learned Torah with his grandfather the Ba’al Shem Tov, who later visited him in dreams. In the Degel Machaneh Efrayim, he gave the shofar blast a radical Hasidic meaning.

Words, Words, Words

The super sad truth about Gary Shteyngart's new novel.

Between New York and Jerusalem

For twenty-five years, Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt, two of the most gifted, influential, and opinionated Jewish intellectuals of the 20th century, maintained a remarkable correspondence. Recently published, these illuminating letters provide a rare glimpse into a relationship that has too often been described as adverserial.

Black Hats, Green Fatigues

They don't like the Z-word, but new haredi IDF soldiers sound a lot like the old Zionists.

Jay D Homnick

A friend in Israel exhorted me to read the Hoffman book, but Tisch's review is as close as I have gotten. I don't know if Tisch is right about Hoffman but he certainly seems right about Hecht...

In the end, his daughter's line, which he quotes lovingly in A Child Of The Century, tells you all you need to know about who he was at home. She said: "My father is the author of my person and other dubious works..."