Brotherhood

Every ten years, a five thousand–person village in the Bavarian Alps called Oberammergau hosts the most popular play in the world. It runs five and a half hours, and about half of the town’s residents perform in the event. Recent seasons of the play included over one hundred performances and drew over five hundred thousand people who came from all over the world. The play, which tells the story of Jesus of Nazareth, is known as the Oberammergau Passion Play. According to legend, its first performance took place in Oberammergau in 1634, after many townspeople died from the Bubonic Plague the previous year. Those who escaped the Plague vowed that if God would put an end to their suffering, they would perform a passion play every ten years. Since that time, the town has continued to fulfill its vow.

Until 1990, the play’s portrayal of the Jewish people only varied in the particular details of how their evil nature was displayed. Sometimes the actors playing Jews wore horns, and sometimes their responsibility for the death of Jesus was underscored with added flourishes in the script. In 1900, an American rabbi named Joseph Krauskopf traveled to Oberammergau from Philadelphia to see the play for himself and was appalled. The play, he wrote:

Introduced, and realistically enacted, a mass of falsehoods, of base inventions against the Jews, that obviously never happened, never could have happened, that are flagrantly self-contradictory, that violently outrage the history and law and religion and constitution of the Jew, and that were forced into the Gospel stories.

Among the Oberammergau play’s twentieth-century admirers was Adolf Hitler, who declared that “never has the menace of Jewry been so convincingly portrayed as in this presentation of what happened in the times of the Romans.” Even after church authorities initiated efforts to reconcile with Jews after the Second World War, the play continued to portray Jews as enemies of the good and murderers of God.

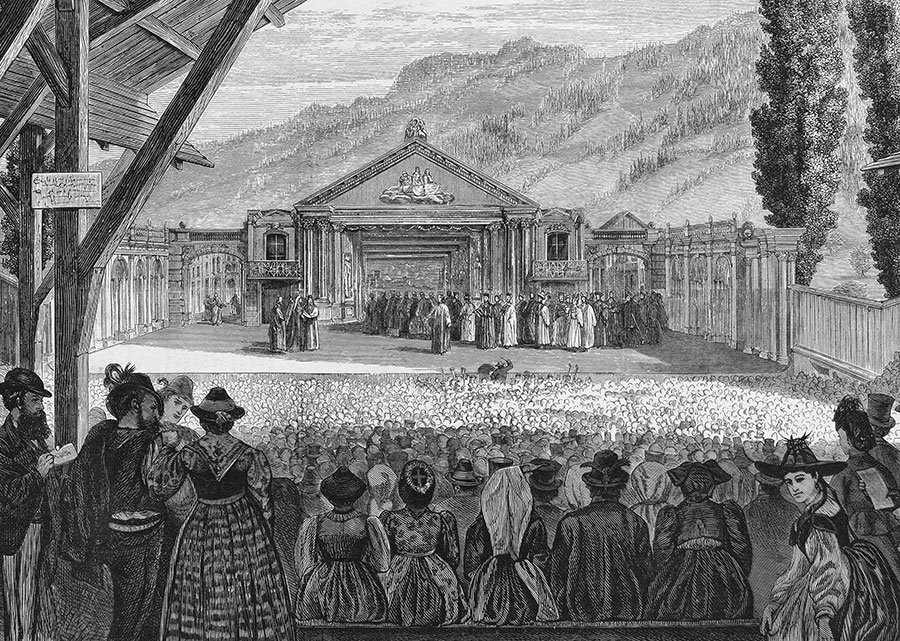

An engraving of a passion play at the nineteenth-century Theatre of the Oberammergau, published by The Graphic, 1870. (Georgios Kollidas / Alamy Stock Photo.)

Jewish complaints over the play’s antisemitism over the centuries pale in comparison to the uproar this summer over changes introduced by a well-known stage director named Christian Stückl. Gone were references to the Pharisees, the Jewish sect derided as snakes and hypocrites in the Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 3:7, 23:27). Gone also was any blame directed against the Jews for the murder of Jesus. There was no reenactment of the famous blood cry of the Jews, who, according to Matthew, declared that “his blood be upon us and on our children” (Matthew 27:25). Rather than wearing devil’s horns, the actors wore kippot, uttered blessings, and transmitted countless visual signals to the audience that Jesus lived and died as an observant Jew.

In light of these and other changes that Stückl has made since he began directing the Oberammergau play in 1990, he has received the American Jewish Committee’s Isaiah Award for Exemplary Interreligious Leadership, the Abraham Geiger Award, and the Buber-Rosenzweig Medal. All of this raises the question: How did the world’s most antisemitic play become an emblem of Jewish-Christian friendship and reconciliation?

The short answer is that Stückl deserves primary credit for this turnaround. Since the time that he was appointed—winning by a single vote—to direct the play, Stückl has been making changes that have systematically exorcised its historic anti-Judaism, with the help of recommendations from Jewish partners at the American Jewish Committee. The longer answer, however, begins in 1965, when the Catholic Church embarked on the most significant religious transformation in history: the renunciation of the idea that the Jewish people are consorts of the devil and guilty of deicide. It was in 1965 that a convening of church leaders known as the Second Vatican Council produced a document known as Nostra Aetate, which stated that “God holds the Jews most dear for the sake of their Fathers; He does not repent of the gifts He makes or of the calls He issues—such is the witness of the Apostle.”Like Stückl’s appointment as director of the Oberammergau Passion Play, Nostra Aetate passed by just a hair.

Karma Ben-Johanan’s remarkable new book, Jacob’s Younger Brother: Christian-Jewish Relations after Vatican II, explores the story of Nostra Aetate and its influence on Jewish-Christian relations. She begins with a brief examination of the church’s historic attitude toward the Jewish people and then provides an in-depth analysis of papal attitudes toward Jews after Nostra Aetate’s publication. The second half of the book reverses the lens and examines Jewish attitudes toward Christianity, beginning with classical rabbinic literature and closing with a study of Jewish attitudes toward Jewish-Christian relations in contemporary times.

Nostra Aetate attracted controversy from the time that it was commissioned by Pope John XXIII in 1960 until its publication (after multiple drafts) under Pope Paul VI in 1965. But Ben-Johanan is less interested in the circumstances surrounding the production of Nostra Aetate than in the half century that followed, when church leaders deliberated over how to interpret and implement the words of the council. Her most incisive analyses are in her chapters about Pope John Paul II (1978–2005) and Pope Benedict XVI (2005–2013), whose attitudes toward the Jewish people have often been interpreted as being opposed to one another, with John Paul II being cast as the conciliator and Benedict XVI as the hard-liner.

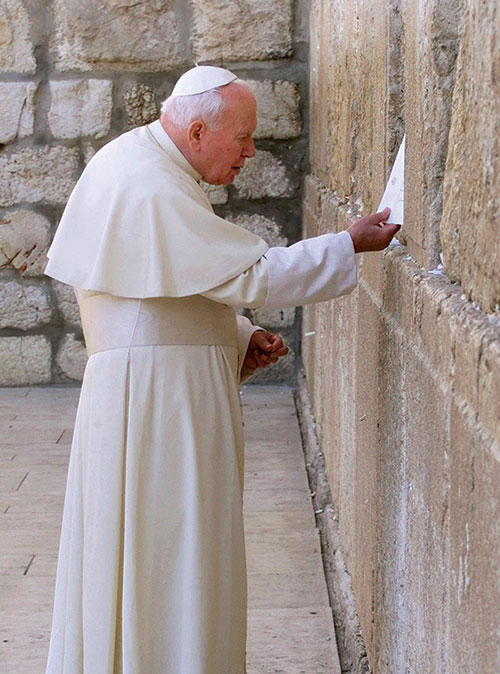

Pope John Paul II places a signed note into a crack in the Western Wall in Jerusalem’s Old City, March 26, 2000. (AP Photo / Jerome Delay.)

Ben-Johanan complicates this common perception. She notes that John Paul II made no major changes to Catholic doctrine. Instead, he preferred to make symbolic public gestures and conciliatory statements. In a 1980 speech to the Jewish community of Mainz, John Paul II cited Paul’s Letter to the Romans and declared that the Jewish covenant had never been revoked. In 1993, the Vatican opened formal diplomatic relations with the State of Israel, and in March 2000, the pope made the first official papal visit to Israel. His visit was viewed as a monumental success and a turning point for Jewish-Catholic relations. He even wrote a heartfelt note that was placed in the Western Wall:

God of our fathers,

you chose Abraham and his descendants

to bring your Name to the Nations:

we are deeply saddened by the behaviour of those

who in the course of history

have caused these children of yours to suffer,

and asking your forgiveness we wish to commit ourselves to genuine brotherhood

with the people of the Covenant.

The pope’s prayer was widely considered to be the most public acknowledgment of the church’s responsibility for the near-destruction of European Jewry. He affirmed this position that same month on the Universal Day of Pardon, when he asked God to forgive the church’s “sins against the people of Israel.” These statements established his reputation as a trailblazer in Jewish-Christian dialogue, but as Ben-Johanan points out, they also obscured the fact that John Paul II did not produce a written policy that developed the meaning of Nostra Aetate. His approach ultimately led to the dwindling of theological work on the relationship between the Jewish people and the church in favor of public shows of dialogue.

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger entered the scene as Pope Benedict XVI in 2005. Ratzinger was a respected theologian who had not cultivated a personal relationship with the Jewish community. Moreover, he oversaw the production of the church declaration Dominus Iesus in 2000, a statement that was widely criticized by liberal Catholics for reasserting the ancient rule that there is no salvation outside the church.

Benedict’s position as a conservative was cemented in 2008, when he issued permission for Catholics to pray for the Jews’ conversion during the Good Friday liturgy. Until 1959, the liturgy included a prayer for the conversion of the “perfidious Jews” (the Latin perfídiam can mean faithless or treacherous). The line had been eliminated by Pope John XXIII, who replaced it with an invitation to “pray for the Jew” but not explicitly for their conversion. Minor changes continued to be made until 1970, when the following version was issued:

Let us pray for the Jewish people, the first to hear the Word of God, that they may continue to grow in the love of his name and in faithfulness to his covenant. Almighty and eternal God, long ago you gave your promise to Abraham and his posterity. Listen to your Church as we pray that the people you first made your own may arrive at the fullness of redemption. We ask this through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

This was a long way from the perfidious Jew, but Pope Benedict’s Good Friday liturgy seemed to turn back the clock, at least partway:

Let us also pray for the Jews that God our Lord should illuminate their hearts, so that they will recognize Jesus Christ, the Savior of all men.

Let us pray. Let us genuflect. Rise.

All-powerful and eternal God, you who wish that all men be saved and come to the recognition of truth, graciously grant that when the fullness of peoples enters your Church all of Israel will be saved.

Through Christ Our Lord, Amen.

Benedict’s changes to the liturgy took center stage in his legacy, but his personal relationships with Jewish intellectuals told a different story. After reading Jacob Neusner’s A Rabbi Talks with Jesus, Benedict contacted him to discuss Jewish and Catholic theology. According to Ben-Johanan, Ratzinger reached out to Neusner precisely because Neusner insisted that Judaism and Christianity had to remain separate and distinct religions.

What are we to make of these two papal legacies? Ben-Johanan concludes that the popes’ divergent legacies were more a product of their differing public styles than their theological positions:

Benedict XVI lacked John Paul II’s charisma, and the public—both in Israel and worldwide—was largely deaf to his theological finesse. As a theologian, Ratzinger sought to promote the relations between the church and the Jewish people on the doctrinal and intellectual plane, in the spirit of the original project of Vatican II . . . [but] Ratzinger’s contributions to the Christian-Jewish discourse came too late, after the sun of theology had already set and both Christians and Jews had turned to other avenues in their efforts to rehabilitate their relations. . . . By the time of Ratzinger’s resignation from the papacy in 2013, not only was doctrine seen as less important than gestures of friendship and face-to-face dialogue, but it was often experienced as downright detrimental.

Ben-Johanan begins her study of Jewish attitudes toward Christianity with rabbinic approaches to its legal status. Was Christianity monotheistic or idolatrous? The question was not merely theoretical. Rabbinic law prohibited various levels of engagement with idolatrous people, including drinking their wine, since the same wine could have been used for idolatrous worship. Yet Jewish authorities did not reach consensus on the question of how to treat the Christian religion.

The twelfth-century legal philosopher Moses Maimonides held that Christianity was idolatrous. At the other extreme was the lesser-known thirteenth-century scholar Menachem Meiri, who claimed that the ethical injunctions at the heart of Christian practice meant that it could not be idolatrous, since idolatry was characterized by moral depravity. Most medieval authorities treated Christians as neither idolaters nor pure monotheists due to their belief in the Trinity.

The dominant Jewish attitude toward Christianity did not substantially change in the twentieth century, even as awareness of the church’s transformation increased. This can partly be traced to an influential essay by the leading Modern Orthodox thinker of the postwar period. In 1964, while discussions of Nostra Aetate were still going on, Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik published an essay called “Confrontation.” Soloveitchik argued that each faith possesses a distinct untranslatable internal vocabulary and self-understanding. He also expressed concern that any dialogue between two faiths, especially when there was a massive power differential between them, would produce theological transactionalism, in which differences were negotiated away. Most of Soloveitchik’s students interpreted “Confrontation” as a warning, or even a prohibition, against Jewish-Christian dialogue on theological issues, though they also interpreted the essay as permitting discussion of politics, social issues, and public policy.

Ben-Johanan, however, highlights an alternate reading of the essay offered by the philosopher Michael Wyschogrod. Wyschogrod notes that for Soloveitchik, the distinction between the theological and the secular is impossible for an observant Jew. Consequently, any sort of dialogue between Jews and Christians had to be of a theological nature. Soloveitchik’s essay thus offered two options: no dialogue at all or a dialogue that was inherently and unavoidably theological. As Wyschogrod wrote:

The option is whether to talk with Christians or not to talk with them. If we refuse to talk with them, we can keep theology and everything else out of the dialogue. If we do not refuse to talk with them, we cannot keep what is most precious to us out of the discussion.

Ultimately, both interpretations of Soloveitchikare less complex than the man himself. In the same year that he wrote “Confrontation,” he also read an early draft of perhaps his most important theological work at an interfaith event at St. John’s Seminary in Brighton, Massachusetts. It was published the following year in the journal Tradition as “The Lonely Man of Faith.”

The influence of Soloveitchik’s position on these matters—whatever that position actually was—has waned over the past twenty years, as many Modern Orthodox Jewish leaders have begun to embrace Jewish-Christian dialogue. Ben-Johanan’s closing chapter explores contemporary Orthodox Jewish dialogue with Catholics as well as with members of the Evangelical community. Modern Orthodox Jews are overrepresented in both of these dialogues, though the conversations tend to attract different kinds of partners: dialogues with Evangelicals tend to be more conservative and political, while those with Catholics tend to be more progressive and theological.

In these discussions, some Jewish theologians, most famously Rabbi Irving “Yitz” Greenberg, have left the door open to the possibility of covenantal truths existing outside of Judaism. Even Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, whose writings are extraordinarily popular in the Modern Orthodox Jewish community, suggested that multiple faiths may bear legitimate covenants in the controversial first edition of The Dignity of Difference. Others, such as Dr. David Berger and Dr. Marc B. Shapiro, have strongly cautioned against this approach.

Ben-Johanan’s focus on Modern Orthodox Jewish approaches to Christianity accentuates the parallels between internal Catholic and Jewish debates about the limits of dialogue. It is in these communities that the tension between the desire to engage with outside religions and the desire to maintain firm religious boundaries is most acute.

It is worth remembering that even after the church extended its hand toward the Jewish people in friendship, the Oberammergau play went on without Jewish input. Moreover, its adoring (and later disappointed) audience might be a more accurate barometer of where things stand between Jews and Christians than the elite world of Jewish-Christian dialogue. Stückl made changes to the play not to accommodate his audience’s religious sensibilities but despite them. Most observant Jews, meanwhile, are uninterested, unaware, or opposed to Jewish-Christian dialogue, especially dialogue of a theological nature.

The relationship between Jews and Christians continuously teeters on the cusp of danger as new generations of Christians and Jews arrive on the scene. Younger generations of Christians in particular are often unaware of how the church has oppressed the Jews, and younger Jews carry the trauma of generations past, often unaware that the church has sought—to a limited degree, and unevenly—to accept its culpability for Jew hatred.

Reverend Dr. Peter Pettit, an academic and Lutheran minister who worked with Rabbi Noam Marans at the American Jewish Committee to provide Stückl with recommendations about how to change the Oberammergau play, is not sure how much they achieved in the long term. In a recent lecture, Pettit argued that Stückl’s changes, and other such developments, cannot guarantee that the next generation of Christians will interpret their scriptures with similar liberality. The future of the Jewish-Christian relationship remains uncertain because it must be written and rewritten in every generation.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Inside-Out

The boundaries between the biblical canon and the Apocrypha have seemed firm for a long time. But what if the walls aren’t that solid?

Michael Wyschogrod and the Challenge of God’s Scandalous Love

The late Michael Wyschogrod may have been the boldest Jewish theologian of the 20th century.

The Mortara Affair, Redux

Bologna, 1857: A six-year old is taken from his Jewish family to be raised a Catholic. Why are we still talking about this case? An archbishop responds.

Maimonides in Ma’ale Adumim

Rabbi Nachum Rabinovitch has been working on his commentary to the Mishneh Torah for the last 41 years. It may be the greatest rabbinic work of the century.

gershon hepner

ST. JOHN’S PASSION AND OBERAMRGAU

J. S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion is contemplative and analytic,

a study in both suffering and transcendence.

treating them as treacherous traitors, transcendentally anti-Semitic,

St. John’s treats Jews as criminal defendants,

“Was ist die Wahreit?” “What’s the truth?” asks Pilate in the version,

of John, quite empty existentially,

that his decision would give rise to of the truth perversion,

less aware than we would be, eventually.

Bach buys the anti-Jewish message of the Gospel John

has written, with his music not redeeming

the Jews who were not betting on a favorite betting on favorite---odd-on!---

whose death the jews allegedly were scheming.

The Jews were blamed for crucifying a good Jew whom Christians came

to think of as the son of God, while Pilate,

by going with the flow, and washing hands, would shift the blame

to Jews, and not with guilt gentile it..

Pilate is in many ways like Melville’s Captain Vere,

so well depicted by a Briton, Britten,

although I have the feeling that he was far less sincere,

absolved of guilt he hoped, while not grief stricken,

his feelngs lacking full regret like people whose

revisions of the passion play at Oberammergau still exclude,

as did Pope Benedict , acceptance of the faith of Jews,

still praying for a world that would be faithlessly unJewed.

I’m afraid that I agree with Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik

that collaboration between faiths is spiritually mistaken,

an approach for which the interfaithful paycheck

is bound to bounce, unfunded not just by those who eat bacon.