Michael Wyschogrod and the Challenge of God’s Scandalous Love

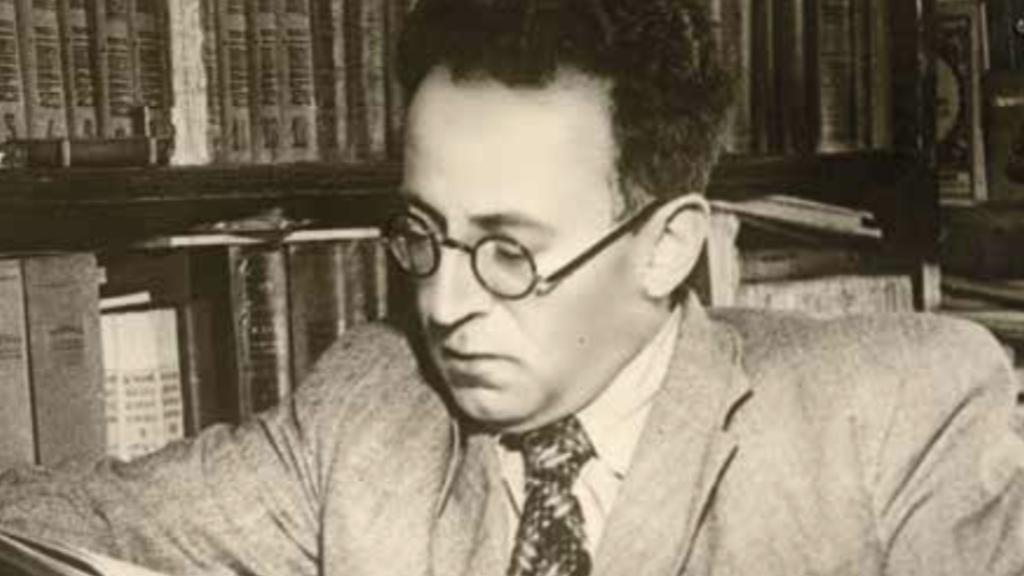

Michael Wyschogrod, perhaps the boldest Jewish theologian of 20th-century America, died at the age of 87 this past December. More than any other 20th-century Jewish theologian, Wyschogrod went against the grain of the dominant trends of modern Jewish thought that emphasized Judaism’s rationality and fundamental confluence with ethical universalism. In doing so, he also rejected the entire tradition of Jewish philosophical rationalism, running from Maimonides to his own teacher Joseph B. Soloveitchik.

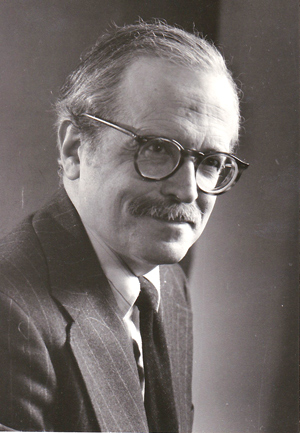

Much like his older contemporary Martin Buber, though for different reasons, Wyschogrod has, at least so far, had his profoundest influence not on Jews but on Christians. Whereas liberal Protestants found in Buber an important and moving account of Christian grace, post-liberal Protestant theologians have found in Wyschogrod a deep articulation of the idea of incarnation and its relevance for rethinking Christianity’s claim to have superseded Judaism. The respective Christian receptions of Buber and Wyschogrod may also reveal what many, though certainly not all, Jews have found less appealing about the two theologians: Buber’s well-known rejection of the authority of Jewish law and Wyschogrod’s almost exclusive focus on the Bible as opposed to rabbinic literature. Yet while Buber self-consciously rejected not just Jewish observance but also traditional Judaism as it came to be practiced in the modern world, Wyschogrod understood himself as a traditional Jew. This apparent disconnect is part of what makes Wyschogrod’s thought so interesting and challenging for our present moment.

Born in Berlin, Wyschogrod escaped Nazi Germany as a young boy in 1939 and immigrated to the United States. He studied at City College, Yeshiva University, and Columbia and went on to a long career as a professor of philosophy, first in the City University of New York system and then at the University of Houston. From the beginning of his intellectual life, Wyschogrod never shied away from intellectual controversy. In 1954, he published the first book-length study of Martin Heidegger’s philosophy in English, Kierkegaard and Heidegger: The Ontology of Existence. In a 2010 essay published in First Things, he continued to insist on Heidegger’s philosophical greatness, despite the fact that, as he put it, Heidegger was “a committed Nazi and a liar.” Strikingly, Wyschogrod contended that aspects of Heidegger’s thought could be saved because, despite a traditional Catholic upbringing in which the Bible was not central, Heidegger was “a thinker whose spiritual life was largely determined by Hölderlin and Rilke [and therefore] could not break with the religious power of the Hebrew Bible.” Despite Wyschogrod’s own philosophical training and acumen, it was an engagement with what he regarded as the anti-philosophical essence of the Hebrew Bible that stands at the center of his Jewish thought.

Wyschogrod announced his central theological claim and its reliance on a kind of biblical literalism in his now classic book of 1983, The Body of Faith. The motivating impulse of the book was his contention that God, Judaism, and the Jewish people are “not grounded in some alleged eternal verities of reason or on some noble and profound religious sensibility that is shared by all people or by a spiritual elite, but on a movement of God toward man as witnessed in scripture.” For Wyschogrod, the Jewish people are the body of faith because God literally dwells within the bodies of Jewish people:

It is of course necessary to mumble a formula of philosophic correction. No space can contain God, he is above space, etc., etc. But this mumbled formula, while required, must not be overdone. It must not transform the God of Israel into a spatial and meta-temporal Absolute . . . With all the philosophic difficulties duly noted, the God of Israel is a God who enters space and time . . . God dwells not only in the spirit of Israel . . . he also dwells in their bodies.

The philosopher in Wyschogrod was not after consistency but rather, like Heidegger, provocation. Just as Heidegger lamented the forgetfulness of being, Wyschogrod bemoaned the forgetfulness of faith in God, which he regarded as the root of Jewish being. In this, Wyschogrod, once again, finds company in Buber, who also sought to revive Jewish faith, albeit through a humanistic interpretation of the Bible and Hasidism. Faith, for Buber and Wyschogrod, is existential, not cognitive. As Buber points out, the Hebrew word most often translated as faith, “emuna,” refers to a trusting relationship with God and not propositional knowledge about God. Buber and Franz Rosenzweig’s translation of Exodus 3:14 is relevant here for appreciating what Wyschogrod means by the body of faith. While a number of Greek, Latin, German, and French translations of the Bible (such as Luther’s and Calvin’s) render “I am that I am” (eheye asher eheye) as a statement about God’s being and God’s eternity, Buber and Rosenzweig insist that this misunderstands the Hebrew, which is not about God’s essence but about God’s presence. Buber and Rosenzweig translate Exodus 3:14 as Ich werde dasein, als der ich dasein werde (I will be there, howsoever I will be there). Like Heidegger, Buber and Wyschogrod prioritize existential presence, or being-there (Dasein), over ontological essence (Sein).

Put another way, God’s presentation of God’s self to Moses is not, as Maimonides and Hermann Cohen thought, for the sake of clarifying philosophically what kind of being God is or is not. Instead, God presents God’s self to Moses to let him know that God is literally there with him and the children of Israel. Wyschogrod parts with Buber in making the perhaps astonishing claim that God is not just present with the people of Israel but that God is literally present, incarnated, in the people of Israel.

The Jewish God, for Wyschogrod, is a personal God who loves his chosen people passionately and, indeed, erotically. In describing God’s special love of the Jewish people, Wyschogrod is at great pains to distinguish between what he calls Jewish eros and Christian agape, that is between a joyful, romantic love and one that is selfless and sacrificial. In doing so, Wyschogrod inverts centuries of Christian criticisms of Jewish particularism and carnality by arguing that Christian agape is not ultimately love:

Undifferentiated love, love that is dispensed equally to all, must be love that does not meet the individual in his individuality but sees him as a member of a species, whether that species be the working class, the poor, those created in the image of God, or what not.

To be sure, a God who loves some people more than others is a difficult concept for modern people to swallow. Yet Wyschogrod insists that far from limiting God’s love for all of humanity, God’s special love for the people of Israel actually makes it possible for God truly to love all people: “When we grasp that the election of Israel flows from the fatherhood that extends to all created in God’s image, we find ourselves tied to all men in brotherhood, as Joseph, favored by his human father, ultimately found himself tied to his brothers.”

Despite Wyschogrod’s sharp contrast between Judaism and Christianity, the connection between “the body of faith” and a Christian conception of incarnation is obvious, and Wyschogrod acknowledges as much:

[T]he Christian proclamation that God became flesh in the person of Jesus of Nazareth is but a development of the basic thrust of the Hebrew Bible, God’s movement toward humankind . . . [A]t least in this respect, the difference between Judaism and Christianity is one of degree rather than kind.

The similarity and the difference between Judaism and Christianity, then, come down to their respective commitments to scripture. For Jews, the Hebrew Bible alone is scripture. For Christians, the Hebrew Bible (or as they call it, the Old Testament) and the New Testament together are scripture. Jews do not reject Christ, according to Wyschogrod, for philosophical or theological reasons. Rather, Jews reject Jesus because no such story appears in the Hebrew Bible. In Wyschogrod’s words, Judaism “does not hear this [Christian] story, because the Word of God as it hears it does not tell it and because Jewish faith does not testify to it.”

The connection between Wyschogrod’s claims and what Jews today often think of as a Christian notion of incarnation is not incidental. As Wyschogrod tells his readers, The Body of Faith is a testament to what he learned from Karl Barth, the most important Protestant theologian of the 20th century. Following Barth, Wyschogrod declares that faith consists in “obedient listening to the Word of God,” which is found in scripture. This theological starting point makes sense of Wyschogrod’s rejection of the Jewish philosophical tradition. As Barth insisted, revelation ought never be confused with, and cannot be mediated by, human reason. Yet as a number of Wyschogrod’s critics have rightly noted, “obedient listening to the Word of God” is not an especially Jewish view.

In fact, as Barth emphasized, “obedient listening to the Word of God” is nothing other than Luther’s notion of sola scriptura (by scripture alone). The irony of an Orthodox Jewish theologian approaching the Bible in this way should be clear. Even if we leave aside any defense of Jewish philosophical rationalism, traditional Jews have never read the scripture “alone” but always as mediated by the history of rabbinic exegesis. It is simply a truism that for Judaism the written Torah (scripture) always stands alongside the oral Torah; indeed, it is clear that, for rabbinic Judaism, written Torah is only authoritative through the medium of the oral interpretive tradition. In following Barth (and Luther) in his approach to scripture, Wyschogrod would seem to be rejecting rabbinic Judaism. Yet, again, the fascinating and indeed important thing about Wyschogrod’s theology is that he claims not to be.

There can be no doubt that Wyschogrod was well aware of this tension, if not contradiction, in his thought. After all, he obviously knew that his Orthodox biblicism was anomalous, and, in many ways, closer to non-traditionalist Jewish thinkers, such as Buber, with whom he was otherwise at odds. But before trying to figure out what Wyschogrod was after in making these claims as a self-consciously traditionalist Jew, it is necessary to appreciate the inherent tension between his theology and his traditionalism in his conception of Jewish election as well. For Wyschogrod, “the body of faith,” that is to say the Jewish people, is not only a testament to God’s revelation but God’s revelation itself. As such, the people is the source of its own salvation. In a striking formulation, he writes that, “Separated from the Jewish people, nothing is Judaism. If anything, it is the Jewish people that is Judaism.”

In understanding this extraordinary claim, it is helpful to consider briefly Barth’s extension of John Calvin’s notion of election. For Barth and Calvin, Christ remains separate from the believer. This is the basis of faith: To have faith in Jesus is precisely not to believe in oneself. Here Wyschogrod parts from Barth and Calvin: The body of faith believes in itself. Jewish faith is, at least in crucial part, the Jewish people’s belief in the very being of the Jewish people. This is where Wyschogrod’s Protestant hermeneutic, i.e., his implicit affirmation of sola scriptura, converges with his definition of the body of faith. The biblical narrative, in Wyschogrod’s reading, allows only one meaning: A personal God with human qualities and human emotions falls in love with Abraham, who (literally) fathers the body of faith.

According to Wyschogrod, there is simply no room for any other interpretation—rabbinic, mystical, philosophical, or otherwise. Ironically, by equating the Jewish people with Judaism, Wyschogrod’s theology, which aims to fully acknowledge God’s scandalous love, ends up removing both God and Torah (oral as well as written) from the conversation. Such theological reductions are not new. We may be reminded here of the Zohar’s famous statement that “Israel, the Torah, and God are one,” a seemingly pantheistic claim that in the 20th century would be turned around and adopted by humanists and nationalists. Yet such a conception would seem to be almost self-refuting for Wyschogrod, given that the central impetus for his claims is refusal to trade the real presence of the biblical God for any form of pantheism or humanism.

As Wyschogrod himself acknowledges, Barth, rather than rabbinic, kabbalistic, or medieval rationalist theology, is his primary influence. I mention this again not to suggest that this influence is, in and of itself, by definition not authentically Jewish but instead to point out the contradiction that it produces: a theology of election premised on God’s absolute sovereignty that makes the Jewish people, and not the Torah, into Judaism. While Wyschogrod is at pains to avoid these implications, it is difficult not to conclude that he has cut God out of the conversation either by presenting a kind of Jewish humanism in the vein of Mordecai Kaplan’s Reconstructionism or Ahad Ha-Am’s Cultural Zionism or, far more problematically, that he has divinized the Jewish people.

We might be tempted to attribute Wyschogrod’s single-minded focus on Jewish election to the influence of Barth’s hyper-Calvinism. But there are Jewish precedents for Wyschogrod’s contentions. Most obviously, the medieval Jewish philosopher and poet Judah Halevi along with Franz Rosenzweig—who considered himself Halevi’s 20th-century incarnation—made such claims about Jewish election. In light of God’s election of the Jewish people, Halevi famously (or infamously) declared Jews biologically and spiritually superior to non-Jews, even going so far as to claim that “Any gentile who joins us [as proselytes] unconditionally shares our good fortune, without, however, being quite equal to us.” (Kuzari 1:27) And Rosenzweig came pretty close to describing the Jewish people and Judaism as “the body of faith” in maintaining that:

While every other community that lays claim to eternity must take measures to pass the torch of the present on to the future, the blood-community [i.e., the Jewish people] does not have to resort to such measures. It does not have to hire the services of the spirit; the natural propagation of the body guarantees it eternity.

Yet for all of his resonance with Halevi and Rosenzweig, the context and timing of Wyschogrod’s arguments are deeply puzzling. Whatever one makes of Halevi and Rosenzweig, it is necessary to recognize that they made their hyperbolic claims about Jewish election in contexts in which Jews were deeply hated and often persecuted. We need but note the subtitle of Halevi’s Kuzari, “In Defense of the Despised Faith” as well as Rosenzweig’s repeated musings on Christian anti-Semitism to see this:

This existence of the Jew constantly subjects Christianity to the idea that it is not attaining the goal, the truth, that it ever remains—on the way. That is the profoundest reason for the Christian hatred of the Jew.

In contrast to Halevi and Rosenzweig’s historical circumstances, Wyschogrod made his arguments about Jewish election in late 20th–century America, when, arguably, Jews had never had it better. To be sure, Wyschogrod’s claims about the body of faith are a response to the Holocaust. Indeed, Wyschogrod implies that far from repudiating Jewish faith, the attempted Nazi genocide of the Jewish people only confirms the Jews’ special status:

[S]in does not drive Hashem [God] out of the world completely. Only the destruction of the Jewish people does. Hitler understood that. He knew that it was insufficient to cancel the teachings of the Jewish morality and to substitute for it the new moral order of the superman. It was not only Jewish values that needed to be eradicated but Jews had to be murdered.

Yet Wyschogrod’s Jewish triumphalism still seems especially jarring in a time in which Jews, as one recent Pew survey has it, are the most popular religious group in America.

But perhaps it is precisely the timing of Wyschogrod’s theology that offers us a clue to what he was largely after, as well as to his enduring relevance. Toward the end of The Body of Faith, he mournfully observes, “That Orthodox Judaism is more easily compatible with a career in nuclear physics, medicine, or law than with being a novelist, composer, or poet is an alarming development.” This, he writes, “bespeaks an ossification in its spirituality of the most serious sort.” Wyschogrod was a traditionalist, but he was also deeply disturbed by the lack of theological, indeed spiritual, engagement within modern Jewish Orthodoxy. His provocative theological claims were, in part, attempts to awaken Jews, and especially traditional Jews, from their spiritual slumber to the joy of their unique relationship with God. Wyschogrod’s contemporary, Abraham Joshua Heschel, similarly sought to awaken traditional Jews from what he called “pan-halachism,” which he described as “a tendency toward legalism…which regards halacha as the only authentic source of Jewish thinking and living.” Heschel, like Wyschogrod, never denied the centrality of Jewish law for traditional Jewish life, but he also, like Wyschogrod, despaired over its myopic effects on the Jewish spirit. Heschel, like Buber, believed that the universalism he associated with Hasidism offered the best chance for reawakening the Jewish people, and the rest of the world, to the joyful love of God. In contrast, Wyschogrod insisted that the vitality of Judaism depends upon God’s special love for the Jewish people and the continued proclamation to the world of God’s scandalous love for them. But is theological triumphalism the best means for reawakening the Jewish spirit?

It is important to reiterate that Wyschogrod’s theological triumphalism has been more appreciated by Christian theologians than by his Jewish contemporaries. Wyschogrod may, in fact, have engaged in deeper theological dialogue with Christians than any other major 20th-century Jewish thinker. He sought out Barth personally, and his work seems to have been important both to John Paul II and Pope Benedict. Perhaps this is precisely because he returned Jewish-Christian dialogue to its most classical and most primitive terms: Which child does God love more? The question that has to be asked, however, is whether this is the right question—not for Christians but for Jews and Judaism today.

In my own view, developments in the Jewish world, especially in Israel, since Wyschogrod published The Body of Faith in the early 1980s strongly suggest that Halevi-like claims about Jewish election are not only theologically disturbing but politically dangerous. Such rhetoric may have made historical sense in contexts in which Jews were politically weak and continually beleaguered, but it is hard to see what good such claims can do for Judaism today, as well as for the relation between Jews and non-Jews. This doesn’t mean that election is not an important theme of Jewish theology, but it is not the only theme.

It also doesn’t mean that Wyschogrod’s theology has nothing to teach us today. Judaism and Jewishness are particularist and collectivist. And it is a deep point that human love, as we actually know it, is particular and directed at unique individuals. Moreover, as Wyschogrod emphasizes, it is only through such particular loves that justice and love for all of humanity can emerge. God’s promise to Abraham encapsulates the complex dialectic between the particular and the universal that is found throughout the Jewish tradition and of course in the Hebrew Bible as well: “I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you; I will make your name great, and you shall be a blessing.” (Gen. 12:2)

Michael Wyschogrod’s theology is a testament to the tension between the particular and the universal in Judaism. Finding the right balance, or perhaps even simply recognizing that such a balance is necessary, remains the challenge facing all Jews today, religious and non-religious alike, as well as much of the rest of the world. In challenging, even provoking, us to rethink this balance Wyschogrod was, and remains, a thinker for our times.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Searching for Ancient Passover in Samaria and Ethiopia

Bloody bucket brigades and white galoshes: Not everyone celebrates Passover with four cups and four questions. Rachel Scheinerman on Passover in Samaria and Ethiopia.

Playing the Fool

Of the many varieties of anti-Semitism, or anti-Judaism, that have plagued the Jews over the centuries, two recurrent general patterns can be identified by the holidays that celebrate triumphs over them: Purim and Hanukkah.

The Bible Scholar Who Didn’t Know Hebrew

The surprising story of Elias Bickerman and his scholarship.

Spiritual Survival

In 1960, the novelist Vasily Grossman wrote to then-premier Nikita Khrushchev with an unusual intention. He wished, he wrote, to “candidly share my thoughts” with the most powerful man in a country that often murdered bearers of candor.

kalman.neuman50

The statement that “Israel, the Torah, and God are one" may indeed be famous (I remember singing the words in day camp) but it does not originate in the Zohar but rather in the writings of M.H. Lutzatto , as shown by Tishbi in Kiryat Sefer 50 (1975) 480-492

ericlinuskaplan

Rather, Jews reject Jesus because no such story appears in the Hebrew Bible. In Wyschogrod’s words, Judaism “does not hear this [Christian] story, because the Word of God as it hears it does not tell it and because Jewish faith does testify to it.”

Is this missing a "not"? i.e. the Word of God does not tell it and Jewish faith does not testify to it?

If it's correct, I don't understand -- how does Jewish faith testify to it?

asmith

Mr. Kaplan,

That is indeed a typo. We are correcting it in the online versions and will print a correction in the next issue. Thank you for bringing this to our attention.

Amy Newman Smith

Managing Editor