Stuck in the Middle

To many of those who have been alarmed over the past few months by all of the antisemitism emerging from the American Left, Pierre Birnbaum may seem inordinately worried about what is being said about the Jews out in right field. For in this new book, first published in French in 2022, the eye of France’s most distinguished Jewish historian is not focused on the ball that is actually heading our way. But it would be unfair to blame him for failing to anticipate what no one quite foresaw. And it would be unwise to think that we need only to concern ourselves with one adversary at a time.

The right-wing antisemitism that most concerns Birnbaum did not show up in America’s early history. Remarkably, Birnbaum writes, “it seems no Jew was ever killed as a result of antisemitism before the first decade of the twentieth century.” And even then, America witnessed nothing like the “deadly acts of violence and innumerable pogroms” that afflicted many European countries in modern times. The Leo Frank affair, which extended from 1913 to 1915 and which Birnbaum discusses at greater length than would seem necessary for his purposes, was bad enough, but Frank’s lynching did not, he insists, mark the beginning, as many have supposed, of “a cycle of antisemitic hate.” Only in the 1930s was there a transposition onto the American scene of “a political antisemitism that emerged out of the French counterrevolutionary tradition, an antisemitism previously so foreign and unknown to the United States.”

Had Tears of History been originally composed for an American audience, it probably would have included a much more substantial discussion of this counterrevolutionary tradition and its ringleader, Édouard Drumont, whom Birnbaum discusses at length in The Anti-Semitic Moment: A Tour of France in 1898. As it is, he has only a few words to say about political antisemitism before its importation into the United States: it was, he explains in his preface, “born in France as a reaction to the admission of Jews into the higher administration of the republic, itself a response against reactionary movements that refused the secularization of public spaces—which was deemed destructive to Christian society.”

This kind of antisemitism first made its way to America, Birnbaum explains, in reaction to Franklin Roosevelt’s appointment of numerous Jews to high positions in his administration. He approvingly cites the analysis of a 1941 report concluding that “the more Jews in political positions . . . the more probably will Jews be used as scapegoats for whatever difficulties the country encounters.” The authors of this report no doubt had in mind the antisemitic attack on the “Jew Deal,” launched by Father Charles Coughlin and some of his less infamous contemporaries. Birnbaum himself also points to Coughlin’s heirs at a later date, when Jews were not so visibly close to the pinnacle of power, including George Lincoln Rockwell’s American Nazi Party and the like-minded white supremacist movement that began to take root in the late 1970s.

Birnbaum makes little attempt to connect the persistence of this menace with allegations concerning the role of Jews in national politics through the immediate post-Roosevelt years. The administrations from Eisenhower’s to George W. Bush’s go almost completely unmentioned in his book, despite the fact that powerful positions were held by Jews in a few of them. The relationship between the political prominence of American Jews and the prevalence of antisemitism preoccupies him again only with the arrival of the Obama administration. Because Obama “decided to commit himself to implementing a welfare state,” he writes, there were many who “pointed out, as was the case under the New Deal, the presence of numerous Jewish advisers at the heart of his political entourage.”

Birnbaum describes how “the Obama Deal replaced the Jew Deal, and ‘Roosevelt, the first Jewish president’ logically became ‘Obama, the first Jewish president,’ a phrase that he himself boasted about, almost in provocation.” The result was, Birnbaum argues, a deluge of antisemitism:

In the name of “America, a Christian nation,” the Tea Party disseminated a satanic view of Jews, denied the Shoah, accused Rothschild of dominating the United States, spread racist propaganda in favor of white domination, and forged ties with supremacists and national organizations that were hostile to Obama and organizing into armed militias.

In short, he writes, “from Roosevelt to Obama, the same reasoning provoked a populist and

antisemitic crisis in identity politics.”

The surge in political antisemitism during the Trump administration is something Birnbaum has to explain somewhat differently. He does not attribute it (nor should he) to the appointment of, say, Gary Cohn as the director of the National Economic Council or Stephen Miller as a White House senior adviser or the highly publicized roles played by the president’s Jewish daughter and son-in-law. At this time, the right-wing political antisemites were not assailing the administration but in tune with it and sometimes supported by it. Already during his campaign for the presidency, Birnbaum writes, Trump “identified with the demands of the Tea Party,” a faction that he too hastily brands as antisemitic, and gave speeches “interspersed with antisemitic allusions.” And as president he did worse.

Trump’s goal was, according to Birnbaum, to remain in tune with some of his radical right-wing supporters, who had given a new twist to political antisemitism. Drawing on the ideology (once again imported from France) of the “Great Replacement,” they accused American Jews of engineering the downfall of white hegemony in America. After their notorious torchlight parade in Charlottesville, Virginia in 2017 led to deadly violence, President Trump was still capable of declaring, infamously, that “very fine people, on both sides” were present on this occasion. The following year there was the murderous attack on the Tree of Life synagogue in Pittsburgh, perpetrated by a man who blamed the Jews for planning the genocide of white people in America. Trump responded very inadequately to this atrocity, according to Birnbaum, and subsequently persisted in casting aspersions on liberal Jews in ways that fueled further eruptions of antisemitic hatred.

The election of Joe Biden and his appointment of an unprecedentedly high number of Jews to cabinet positions, including the most important, occurred only shortly before the publication of the original French version of the book, and Birnbaum could only speculate about the effect this might have. Will these developments, he asks, help to rejuvenate the “myth of the Jewish Republic” that “emerged in the United States in the 1930s with Franklin Roosevelt, and then again in 2000 with Barack Obama?” Writing in 2022, Birnbaum didn’t pretend to know. But he could not conceal his pessimism. In his book’s conclusion, he muses darkly about “a populist mobilization infused by radical alt-right currents.”

How bad, though, does he fear things might become? In assessing current conditions in the United States, Birnbaum is by no means blind to positive signs, but he is prone to focus on the worst. The attack on the synagogue in Pittsburgh, he writes, turned “the long history of American Jews” into “a nightmare.” And in order “to protect themselves from any further large-scale attacks in 2021 . . . a number of American Jews have decided to arm themselves.” In the end, however, Birnbaum doesn’t explicitly anticipate a descent into even worse violence. He sketches, instead, the current situation of the Jews in his own country, France, where in the face of mounting antisemitism many have chosen to “withdraw into their communities and turn their hopes, as though by substitution, to the Jewish state as an imagined home.”

Birnbaum’s fears are the product not only of observation of the current scene but of deep reflection on the work of leading modern Jewish historians. A learned reconsideration in the first part of his book of some of the writings of Salo Baron and his “most brilliant student,” Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi, leads him to conclude that, “consciously or not,” they were in agreement with the view expressed by the Austrian Jewish writer Stefan Zweig in the 1930s: “There is nothing that has stirred the anti-Semitic movement as much as the fact that the Jews made themselves too visible in various countries, in various aspects of political life, and all too often as leaders.” To remain safe, the Jews, Baron and his student thought, should “stay on the sidelines.” Birnbaum apparently shares this opinion.

I do not by any means wish to make light of Birnbaum’s fears with respect to antisemitism stemming from the right. But I doubt that the situation is now as dire as he, from a considerable distance, perceives it to be.

That the right wing of the 2010s branded Obama’s administration as a tool of the Jews just as thoroughly as its predecessors had branded FDR’s is, it seems to me, something that Birnbaum asserts but fails to substantiate. He does not really engage in a detailed comparison that would warrant such a conclusion, and the evidence he does provide is sometimes dubious. Take, for instance, his treatment of the Tea Party, which he depicts as a movement riddled with political antisemitism. The idea that some Tea Party groups on occasion provided a platform for antisemites is amply supported by Devin Burghart and Leonard Zeskind’s 2010 book Tea Party Nationalism, on which Birnbaum relies. Saying, however, that the Tea Party, as such, was antisemitic is a huge oversimplification. More focused studies, such as Chip Berlet’s 2010 article “Taking Tea Partiers Seriously,” which investigated the Tea Party’s stance toward “liberals, people of color, immigrants, and other targets,” and a 2018 article by Kristin Haltinner, “Right-Wing Ideologies and Ideological Diversity in the Tea Party” (both of which are also cited by Birnbaum), barely mention Tea Party attitudes toward the Jews at all.

When Trump claimed, therefore, in 2011 to represent what he called “ingredients of the Tea Party,” he was not, as Birnbaum suggests, clearly endorsing or even winking at political antisemitism. It probably didn’t even occur to him. Since then, he has, to be sure, often flirted with or piggybacked on antisemitism but not of the variety that Birnbaum traces back to the Roosevelt administration and, ultimately, to turn-of-the-century France. The antisemitism of the Trump era was of a different kind. It was not animated, as Birnbaum himself makes clear, by hostility toward “state Jews.”

Enough time has now passed to answer Birnbaum’s question as to whether Biden’s appointment of many Jews to high positions in his administration would rejuvenate an American version of Édouard Drumont’s antisemitic and antidemocratic “myth of the Jewish Republic.” It has not. I’m sure, of course, that if I chased down neo-Nazi sources on the Internet, I would come up with more crude, half-erroneous lists of Jews who were sitting in seats of power and using them to the benefit of their people and to America’s detriment. But the vast majority of even the most vociferous right-wing despisers of the current administration strike no such note. For the more or less open antisemites among them, it’s not Ron Klain or his Jewish replacement as the president’s chief of staff, Jeff Zients, or Antony Blinken or Janet Yellen who most ominously represents the Jewish threat; it’s a man who holds no public office at all: George Soros. Even if, as Pierre Birnbaum appears to wish, American Jews were to evacuate public life, the leading financiers among them would supply antisemites with all the targets they need.

Staying on the political sidelines, therefore, wouldn’t solve any Jewish problems. Speaking for myself, I am glad that I live in a country where a leader of the majority party could make a speech like the one Chuck Schumer delivered on the Senate floor in November. Many of the new antisemites in America, he declared in his remarkable address, “aren’t neo-Nazis, or card-carrying Klan members, or Islamist extremists.” They were, instead, leftists whom liberal Jews such as himself had generally regarded as political allies:

Not long ago, many of us marched together for Black and Brown lives, we stood against anti-Asian hatred, we protested bigotry against the LGBTQ community, we fought for reproductive justice out of the recognition that injustice against one oppressed group is injustice against all. But apparently, in the eyes of some, that principle does not extend to the Jewish people.

But it should, Schumer insisted. “All Americans share a responsibility and an obligation to fight back whenever we see the rise of prejudice of any type in our midst.” If taking part in the democratic system on all levels entails certain risks-and I don’t think that they are by any means as great as Birnbaum supposes-then our leaders, like Senator Schumer, will have to ignore the message of Stefan Zweig and continue to take them.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Emancipation Terminable and Interminable

The modern "emancipation of the Jews" can be said to have begun a lot earlier than historians used to think, but has it really not come to its end?

Montefiore and the Politics of Emancipation

More than a shtadlan.

Jews on the Loose

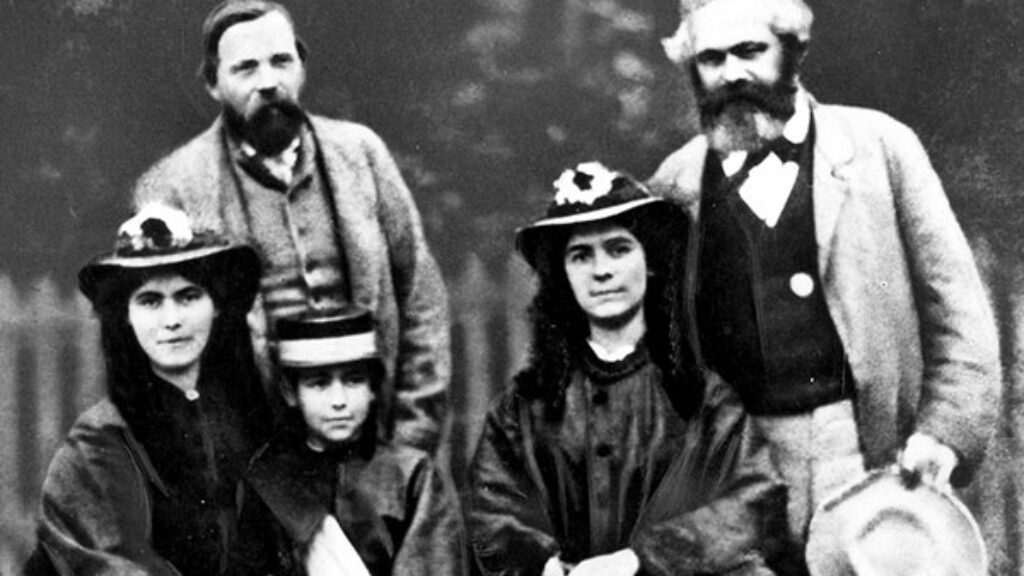

If fame is when everyone understands it is you when only your first name is mentioned, Groucho (Marx) certainly qualifies.

Marx and the Jewish Fingerprint Question

Are there hints about Marx’s thoughts on Judaism in his writing, and if so, what do they say?

gershon hepner

WHAT STEFAN ZWEIG REFUSED TO ADMIT

Refusing to accept the passing of the world of yesterday, like far too many Austrian and German Jews,

imagining he still inhabited the world from which he’d been expelled,

Stefan Zweig became a paradigm for all those who----not just in that era but today as well---refuse

to admit that by a shock they have not just been shocked, shocked, but have been shelled.