Portrait of an Artist “Like Buttah”

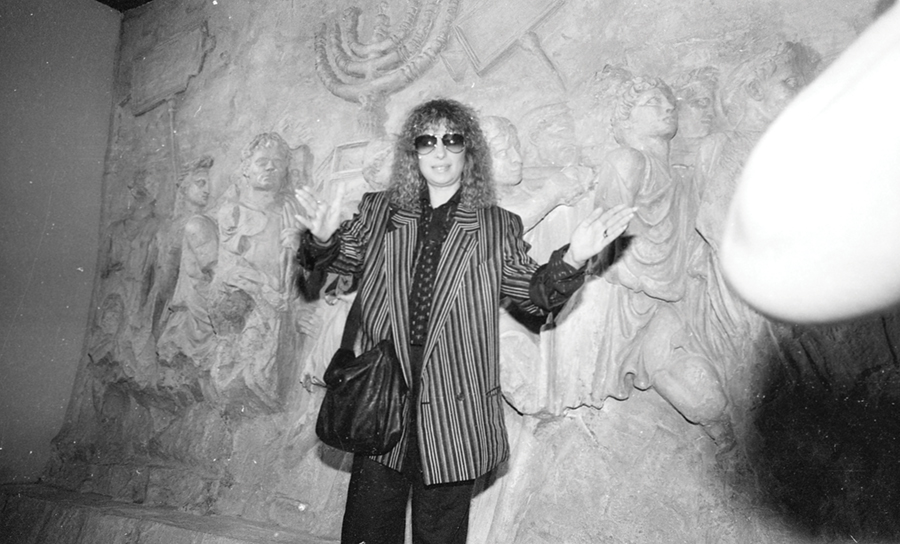

If there is one theme that ties together Barbra Streisand’s new memoir, My Name Is Barbra, it is control. There is the complete creative control she exercised over her albums, from songs to artwork—a feat guaranteed through a deal with Columbia Records in 1962 that sustained Streisand’s music career through six decades and thirty-four number-one albums. She also had complete control over her television performances and live concerts, which she has avoided . . . because they are so hard to control. Add to this the chutzpah to take control over her film projects, even as a fledgling actress working with Hollywood giants, whether they welcomed her input (Funny Girl’s William Wyler, The Way We Were’s Sydney Pollack) or not (Hello Dolly’s Gene Kelly, producer Ray Stark). All of which has led to her trailblazing an unprecedented show business career as a quintuple hyphenate (actress-singer-writer-producer-director). There are even three points in My Name Is Barbra in which Streisand recalls controlling the weather, through prayer, patience, and a will so forceful that it seemingly can part clouds, stop rain, and delay the sunset if it means maintaining her directorial vision.

When one considers the impact that Streisand’s work has had on American popular culture, it’s no wonder she should want creative control over her films, albums, and concerts. By her own recollection, she is almost always right, a judgment that the quality and pervasiveness of her oeuvre tends to reinforce. My Name Is Barbra is, in some ways, her greatest achievement. It is a performance of constructed intimacy and calculated candor in which Streisand takes control of her own narrative for almost one thousand pages, exploring six decades of artistic, philanthropic, sartorial, and culinary triumphs and misty water-colored memories.

In the long-winded but never-tedious forty-eight-hour audiobook version, the memoir is rendered even more accessible and entertaining by Streisand’s fast-talking, Brooklyn-accented reading of her own words. In this way, the book acts as a natural extension of Streisand’s carefully curated persona, further underscored by an easy, conversational writing (and speaking) style that elicits the feeling of catching up with an old friend, perhaps over a pint of coffee ice cream. Streisand beckons to us through the meandering anecdotes, gossip about difficult costars, and ruminations on food that seemingly confirm everything we already knew about her.

At the same time, however, we gain insight into Streisand as an artist who, despite her myriad successes, castigates herself as “lazy” and focuses on the projects she missed out on (The Normal Heart and Gypsy, among others) as much as the ones she completed to critical and popular acclaim. Streisand still smarts over the review of the 1962 show I Can Get It for You Wholesale that described her as an “amiable anteater” and resents the refusal by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to take her seriously as a director decades later, even though her films were acknowledged for their achievements in music, writing, cinematography, and acting. The dichotomy between entertainment icon and working artist, and Streisand’s own oscillation between the two, is ultimately what makes My Name Is Barbra such a fascinating read.

Streisand describes herself as “an actress, who just happens to sing,” but she discusses films as a director, and the bulk of her memoir details her trajectory from actress to producer to writer-director in ways that are both expected and unexpected. Of course, we hear about the hits—Funny Girl; Hello, Dolly!; The Way We Were; Yentl; The Prince of Tides—in effervescent if technically exhaustive detail. There are also behind-the-scenes gems. For instance, when Streisand insisted on singing “My Man” live for the final scene of Funny Girl, director William Wyler had to reopen the set, and Omar Sharif made a special trip to stand in the wings in case Streisand needed “to look at him . . . to trigger [her] emotions.” There is also hot, sometimes retaliatory gossip: Gene Kelly and Walter Matthau (neither of whom Streisand remembers with particular regard) bullied Streisand on the set of Hello, Dolly! in an attempt to get back at her for breaking off an affair with their friend, the Broadway star Sydney Chaplin. She also describes moments of on-set improvisation, such as the scene in The Way We Were when she brushes back Robert Redford’s hair when they reconnect after college. It played so well in the dailies that she brought it back for several later scenes in the film. In short, My Name Is Barbra satisfies even the most fanatical Streisandian’s appetite.

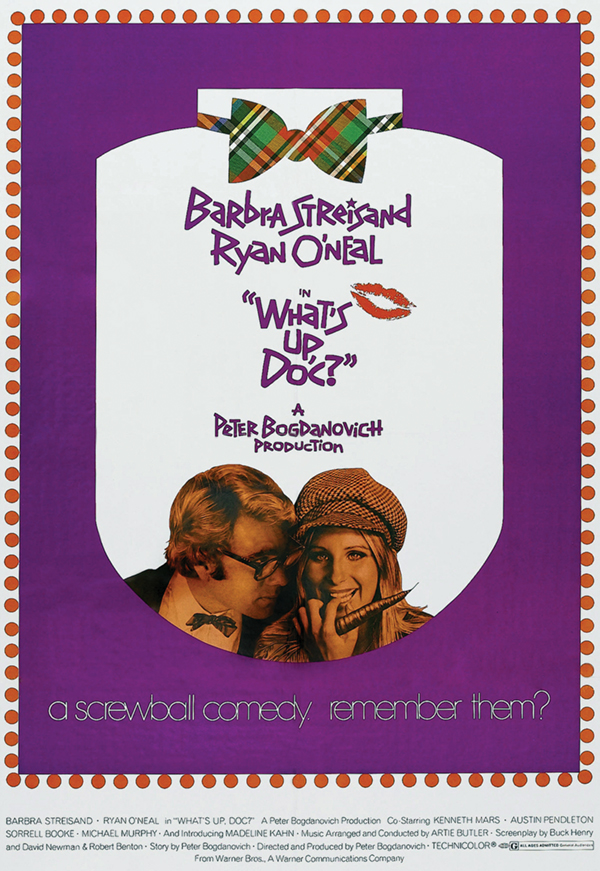

But it’s her ruminations on the flops that provide some of the most compelling insights into Streisand’s artistry. Take, for example, her reflections on 1972’s Up the Sandbox. In 1969, Streisand, Paul Newman, and Sidney Poitier set up First Artists, an artist-controlled production company, and this was her first film produced by First Artists (along with her own production company). Adapted from Anne Roiphe’s best-selling novel and directed by Irvin Kershner, the film tells the story of a young wife and mother who, bogged down and bored by her day-to-day life as a homemaker, daydreams about geopolitical and sexual intrigue (a Castro-like revolutionary dictator makes a memorable appearance). Streisand was drawn to the film by its feminist politics and by the fact that it was “more like a European art film than a Hollywood star vehicle” in the way it blurred the lines between fantasy and reality. However, it was marketed as if it were the follow-up to Streisand’s screwball hit What’s Up, Doc?, which had been released earlier that year. As Streisand explains:

I am so proud of this film . . . even though it was a total flop. I remember taking a friend to see it at a theater in Westwood right after it opened, and there were only four people there. I was so embarrassed. And it really shook me. It felt like audiences didn’t want to see me as an ordinary housewife. They weren’t interested in the unadorned me. This movie had no elaborate sets and no fancy costumes, and they clearly preferred the bigger Barbra, belting out a song or making jokes. . . . People want to put you in a mold. They want you to play the same part over and over again because that’s how they first saw you and liked you. But that can be stifling. And just as I was trying to grow as a person, I was also trying to grow as an actress.

Such moments of honest reflection elevate My Name Is Barbra from the typical celebrity memoir to something that invites a deeper inquiry into how we conceive the relationship between a popular artist, her art, and her audience.

Her ruminations on Up the Sandbox are surprising in their candor: she wallows with the reader in the disappointment of its commercial failure and wistfully revisits Pauline Kael’s positive review (a “joyful mess”) fifty years later. It is tempting to wonder what Streisand’s career might have looked like if she had been able to convince moviegoers to come see her as an “unadorned” housewife in an experimental film and her career had taken a slightly different direction. Four years later, A Star Is Born, the ultimate Streisand star vehicle,became First Artists’s biggest selling picture. And Streisand did it all as star, producer, and proto-director. Although many found the film overwrought (Kael: “sentimental, without being convincing for an instant”), it also marked Streisand’s growing understanding of how to merge the “bigger Barbra” with understated and complex characters who oscillate between vulnerability and strength.

That dichotomy of vulnerability and strength ultimately informs the whole of My Name Is Barbra, even as Streisand tries to fit her life and career into a dramatic linear narrative that, in many ways, mirrors the plots of her most famous films. She is a scrappy underdog written off for her peculiar (“too Jewish”) looks and big personality who triumphs over (mostly male) critics who undervalue her talent, don’t understand her vision, and misconstrue her independence as unfeminine. She, in turn, is romanced by men who are not right for her, and rather than compromise control over the creative, personal, and professional aspects of her life, she goes it alone, maintaining both her dignity and what Letty Cottin Pogrebin has described as “Her Intense Natural Self.”

My Name Is Barbra begins as a bildungsroman: the young artist has a difficult relationship with her controlling, jealous mother, to whom the book is partly dedicated, and an abusive, critical stepfather. Subsequent chapters treat each stage of her career as a signpost on the journey to overcoming her childhood trauma and becoming “Barbra.” Her talent and her refusal to listen to naysayers, in or out of her family, propel her to each stop along the way—first to gigs in small nightclubs, then to a breakout role on Broadway (where she met and eventually married Elliott Gould, the first of the not-quite-right love interests unmanned by her successes), and then to Funny Girl, the role that finally established the place of an “odd, skinny girl from Brooklyn” in Hollywood.

Streisand’s penchant for leaning into her outsider Brooklyn roots, emphasizing her feelings of being an outsider, and highlighting her self-doubt even as she recounts her constant push for more control drives her narrative. Even Streisand’s meeting with her longtime husband, James Brolin, is a subplot of her artistic career. She was in the middle of editing The Mirror Has Two Faces, her final directorial feature, and one of the only major films in which her character actually gets the guy, when, without even looking, she got the guy. Her relationships with other famous friends (Marlon Brando!), enemies (Walter Matthau!), and lovers (Warren Beatty . . . maybe?) are framed similarly. Of course, this is her life, but the telling of it bears the traces of a seasoned filmmaker looking to produce a good story centered on a star performance.

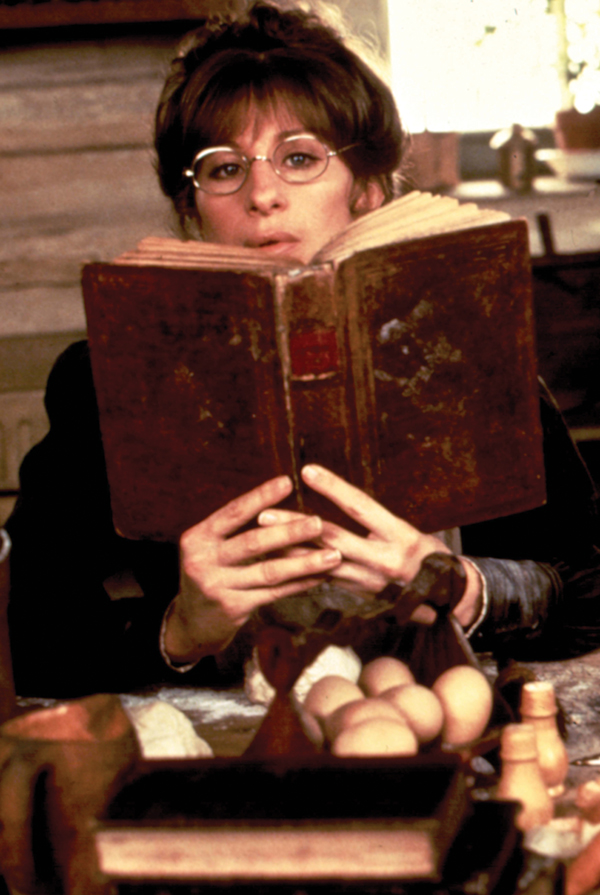

Authenticity, however, can be found amid the artifice. Streisand is at her most real when she is talking about the project that marked her directorial debut. She read Isaac Bashevis Singer’s short story “Yentl the Yeshiva Boy” just before the premiere of Funny Girl in 1968. It took her fifteen years to make it into a movie, and the three meaty chapters that tell her story are at the core of the memoir. Yentl was her most personal (and overtly Jewish) project, and she clearly regards it as her masterpiece. It won Golden Globes for Best Picture and Best Director but was snubbed at the 1984 Academy Awards, winning only for Best Original Song Score.

The story of Yentl is, in many ways, the story of Streisand fighting against her detractors—studio executives who dismissed the script, cast, and subject matter as “too Jewish,” critics who questioned whether Streisand actually directed the film without help, loved ones who tried to convince her to move on from the project, and even Singer himself, who denounced Streisand’s feminist reinterpretation of the original source material. Ultimately, she not only asserted creative control but took ownership of her Jewishness, her femininity, and the power that came from celebrating both:

When the studio executives refused to see beyond the Jewish context of Yentl to the larger theme of gender equality . . . this was about a woman who simply wanted the same opportunities as a man . . . their real concern was unspoken, but I could feel it. They did not want to draw attention to Jews and their world. As I wrote in my journal, Jews were apparently considered too “different, alien, especially now, and again, and it seems always.” . . . I’ve always been proud of my Jewish heritage. I never attempted to hide it when I became an actress. It’s essential to who I am. And I wanted to make this movie about a smart Jewish woman who represented so many qualities I admire.

Over the course of her career, Streisand has been this “smart Jewish woman” for millions of American Jews (and especially American Jewish women) looking to see their own experiences reflected back at them.Her open Jewishness—not just in the context of her films but also in her philanthropy and in her warm relationship to Israel—broke new ground.

Of course Streisand was not the only distinctively Jewish Jew who broke through in the 1960s, but she was the most spectacularly successful. She constructed her career and her persona through sheer force of will to become one of the most successful, most decorated, and most recognizable artists of the past sixty years:

I became a movie star, even though I didn’t fit the conventional image . . . me with my asymmetrical face, my notable nose . . . and my big mouth. I had a dream, and I didn’t listen to the people who tried to stop me. I just kept forging ahead, and who knows? Maybe I did will my vision into reality. . . . It was bashert.

Her memoir—long, yes, but also provocative, compelling, funny, heartbreaking, and, perhaps most importantly, very difficult to put down—is a testament to the virtues of control. The artifice of My Name Is Barbra is, in the end, far less important than its impact: over the course of nearly one thousand pages, Streisand provides a portrait of a Jewish female artist whose chutzpah has carried her across six decades of groundbreaking work and whose name, nose, and canon will live on in American pop culture.

Suggested Reading

Kibitzing in God’s Country

It may come as a surprise that there is an entirely different Catskills, a Catskills that doesn't involve Grossinger's, bungalow colonies, or Jews, in the words of Billy Crystal, eating "like Vikings."

Storytelling, or: Yiddish in America

The basic recipe of Isaac Bashevis Singer’s later novels called for a guy with two wives or lovers who ping-pongs between them for a couple of hundred pages and then runs away. And yet this new collection of Singer’s essays, reminds us that he was not only a great storyteller, but a great champion of the importance of stories for art and for life.

Reprise of the Repressed

So much of American Jewish pop-culture sets out to shame the audience, one wonders why there's such an appetite for it.

Revisiting Hill 24

The first movie I ever saw, not counting Dumbo, was Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer, a landmark black-and-white film about Israel’s War of Independence . . .

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In