Revisiting Hill 24

The first movie I ever saw, not counting Dumbo, was Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer, a landmark black-and-white film about Israel’s War of Independence. This was back in 1955, when the Jewish state and I were seven years old. My parents, both Hebrew teachers, took me to the old Vogue Theater on Coney Island Avenue to see it.

Widely forgotten today, Hill 24 was the first Israeli feature film, with a big budget at $400,000. The dialogue is in English with dollops of Hebrew. Directed by British filmmaker Thorold Dickinson, it’s an engaging neorealist melodrama, neatly packed into 101 minutes, with a stirring score by Paul Ben-Haim performed by the IDF Symphony Orchestra and a memorable cameo by Shoshana Damari, the great Yemenite Israeli chanteuse, as a Druze ululating in Arabic. It was well received at the Cannes Film Festival. The film apparently made the requisite impression on me, culminating in my move to Jerusalem three decades later.

I watched it for the umpteenth time on YouTube recently, comfort food in the Year of the Plague. Within the slim genre of English-language films about the War of Independence, Hill 24 holds up the best, certainly better than Otto Preminger’s overlong Exodus or the star-studded Mickey Marcus biopic Cast a Giant Shadow, Hollywood extravaganzas that projected diaspora anxieties onto the State of Israel. Paul Newman’s incongruous Ari Ben Canaan, the blue-eyed sabra superhero of Exodus, was patently constructed to inspire assimilating American Jews. Cast a Giant Shadow, starring Kirk Douglas as the true-life military wizard Marcus (plus John Wayne as an American general), was scripted and directed by Melville Shavelson, a former gag writer for Bob Hope, and filled with nervous one-liners about Noah’s Ark and noodle soup. Unlike Exodus, Cast a Giant Shadow bombed at the box office. Douglas declared in his memoir The Ragman’s Son: “Though Mel was Jewish, he was not Jewish enough. The movie needed to be done by someone with deep conviction, but Mel was cynical about being Jewish. And I think had he not been so, the picture would have been stronger.” Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer was, and is, a different story—and well worth a visit this Yom HaAtzma’ut.

In 2003, director Martin Scorsese told a British interviewer that “Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer is a unique film,” comparing Dickinson’s “rich sense of place” in action sequences to that of Alfred Hitchcock. “Dickinson is never afraid to push the emotion in a scene, and that’s rare in British film-making.” The movie begins with a map of Israel and a quick history lesson on the birth of the state and the 1948 war. Cut to smoke and thunder of artillery shells, four dead Israeli soldiers on a hillside. We see their faces clearly, with quick flashbacks to their living selves, so we begin by knowing how the story will end. I used to think this was a plot spoiler, but this time around, I read it more generously. By opening and closing with a stark tableau of sacrifice on a Judean hill, the film invites the viewer to excavate its strata of myth and midrash.

A diverse quartet of soldiers eagerly reports for duty: the Irish Gentile, the American Jew, the Ashkenazi sabra, and the Yemenite Israeli nurse. Their Jerusalem commander (played by Yossi Yadin, the brother of Yigael, the archeologist and army chief of staff) explains their dangerous nighttime mission. They must seize and claim the strategic Hill 24 before the truce with the Arabs takes effect at 4 a.m. on July 18, 1948. Holding the Judean hills is vital to the fate of Jerusalem and the Jewish people. Cast a Giant Shadow actually rested on the same premise, the same truce, and a similarly tragic ending, but Hill 24 is refreshingly free of movie stars, lame jokes, and belly dancers.

In the back of the army truck that carries them to their destiny, the members of the squad share their backstories, starting with Jim Finnegan (Edward Mulhare, who later starred in The Ghost & Mrs. Muir on TV). As a British policeman serving in Haifa, he had been assigned to capture Holocaust refugees, illegal immigrants to British Mandatory Palestine. In the process, he fell in love with Miriam Mizrahi (Haya Harareet, later the love interest in Ben-Hur), a Jew, who was a supporter of the Zionist underground. Exciting chase scenes in hilly Haifa, which held my boyish interest in 1955, showcase Dickinson’s technical talents. Inevitably, Finnegan, an incurable Irish romantic, switches sides, quits the police, and volunteers for the Haganah, pledging his love for Miriam in Hebrew: “Gam ani ohev otach,” he pronounces gamely.

Philosemitic Finnegan is a forerunner of Kitty Fremont in Exodus, the Presbyterian blonde nurse raised on an Indiana farm, perfectly played by Eva Marie Saint. A young widow keen to explore the world, she fetches up in Cyprus, where we find her drinking whiskey with a British general and his outrageously antisemitic aide, Major Caldwell (Peter Lawford). Kitty admits feeling “strange” among Jews, but when she visits a British detention camp for Jewish refugees, her Zionist journey is launched. In Hill 24, Finnegan quite naturally identifies with the downtrodden Jews, and the maverick British director identifies with Finnegan.

The screenplay of Hill 24 is credited to Peter Frye and Zvi Kolitz, “from the stories by Zvi Kolitz,” with shooting script credits to director Thorold Dickinson and his wife, Joanna. Kolitz, who also coproduced the film, was born in 1912 in Lithuania, the son of a prominent rabbi. He went to Palestine in 1940, joined the Irgun, and was jailed by the British. He later settled in New York, where he coproduced The Deputy, the 1964 Broadway sensation about Vatican complicity with Hitler. His younger brother Yitzhak stayed in Israel and became the chief rabbi of Jerusalem. Thorold Dickinson was the film’s skillful director, but the remarkable Zvi Kolitz was its very Jewish auteur.

Kolitz’s creative legacy was cemented in 1946, when he was living in Buenos Aires as a Revisionist Zionist emissary. The local Jewish paper, Di Yiddishe Tsaytung, published in its Yom Kippur edition a short story by Kolitz, translated as “Yosl Rakover Talks to God.” The fictional premise is that Yosl is a Gerer Hasid who has lost his wife and six children in the Warsaw Ghetto. His last words have been recovered in a glass bottle buried in the ashes of the ghetto. Yosl had three bottles of gasoline in hand—“as precious to me as wine to a drinker”—two to set on fire and hurl at the Nazis, the third to incinerate himself after stuffing his final testament in the bottle.

“God has hidden His face from the world,” Yosl declares. “I believe that when the forces of evil dominate the world, it is, alas, completely natural that the first victims will be those who represent the holy and pure.” How can he retain his faith in God in the midst of the Holocaust? “I believe in His laws even when I cannot justify His deeds,” Yosl writes. “I love Him. But I love His Torah more.” In 1954, a Yiddish journal in Tel Aviv reprinted the story, claiming it was true. Kolitz, who had never set foot in Warsaw, protested that it was fiction but was nonetheless accused over the years of forgery.

The middle episode of Hill 24 is the angry beating Jewish heart of the film and an epilogue of sorts to Yosl Rakover. It’s the story of Alan Goodman, an American Jewish tourist who felt an itch to travel, stuck a pin in a map, and landed randomly, so he says, in Jerusalem. (Goodman was played by Michael Wager, son of the American Zionist leader Meyer Weisgal.) In the waning days of the Mandate, lounging by the King David Hotel pool, Goodman talks politics with two locals, a Brit and an Arab. “Either you push us into the desert, or we push you into the sea,” remarks the latter, shoving Alan into the pool. Cut to the banner headline of the Palestine Post: “STATE OF ISRAEL IS BORN.” Goodman realizes that the Jews must fight to survive, and he, too, joins the Haganah.

Wounded in the losing battle for the Jewish Quarter of the Old City—a gripping sequence—Alan wakes up in a makeshift hospital. His nurse, Esther Hadassi, is the same young Yemenite who now hears his story in the army truck. A kindly gray-bearded rabbi comes to comfort Alan. “I hate your God,” the American exclaims bitterly. “Where is he, every time we need him?” The rabbi, citing the 13th-century Judeo-Spanish sage Ramban, replies in virtually the same words as Yosl Rakover: “This is the heart of the matter: That which is most holy suffers the greatest destruction.” Goodman shoots back: “That sounds pretty cockeyed to me. Why should those who truly believe in God suffer the greatest destruction?” The question remains unanswered as we segue to the mournful exodus from the Jewish Quarter, shot with a documentary feel by Dickinson.

The Holocaust theme of Hill 24 reaches a powerful climax in the desert. David Amiram, a compleat sabra, rude, charming, and brave, is played with relish by Arik Lavie, a popular Israeli singer and actor who looks nothing like Paul Newman. “I speak six languages,” the voluble Amiram boasts to his comrades in the truck. “The time I spoke best, and really best, was when I didn’t say anything at all.” Three weeks earlier, fighting the Egyptians, Amiram had found himself in hand-to-hand combat with a wounded enemy soldier, a foreign mercenary. The enemy soldier pulls the pin from a grenade, and Amiram manages to wrestle it from him and is about to fling it away but instead jerry-rigs a pin and keeps it. “These things cost money,” he says in Hebrew. Under booming artillery fire, Amiram coolly carries the man into a cave, talks to him in English as he tears open the enemy’s shirt to tend to his wounds with antiseptic powder—and sees his swastika tattoo and SS insignia. Amiram utters one word—“Nazi!”—and falls silent.

The German, pleading for his life, can’t stop talking: he was only following orders, what else could he do, the führer was so charismatic. “We had to obey; he could do with us anything he wanted!” As he babbles on, Amiram says nothing. In the presence of the Holocaust, of God’s absence, there are no words.

The Nazi mercenary yammers frantically about Judeo-Christian forgiveness—after all, Jesus was a Jew. He uncorks vicious antisemitic slogans, imagines Amiram as a nebbish in a bowler hat and Jude badge, but Annie Hall this is not. “Give me the gun; I’ll do it for you,” he dares the Jew. “You have the word of a German officer.” Amiram snickers, breaks into a big laugh. The Nazi rises shakily to his feet, barks “Heil Hitler,” keels over, and dies, having talked himself to death. Israeli planes strafe Egyptian tanks as Amiram’s story ends in triumph.

Back in the army truck, Esther (Margalit Oved, born in Aden, principal dancer of the Israeli troupe Inbal) modestly tells the others she was born nearby, in these beautiful Jerusalem hills, and sings a folkloric Yemenite song. No flashback for her, but Esther, the supportive nurse, becomes the heroic soldier who saves the day in the film’s final moments. When UN truce supervisors reach Hill 24 the next morning, they find the four dead soldiers splayed on the hillside and, clutched in Esther’s hand, an Israeli flag, proof that the patrol has claimed the hill for Israel.

The finale includes aerial shots of 1950s Israel, new housing tracts and bustling commerce in the Jewish state. Instead of the words “The End” appearing onscreen, Kolitz and company announce “THE BEGINNING.” Kitschy perhaps, but effective; surely it spoke to me in 1955.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Jewish Pittsburgh in Pictures

There is more to discuss in the coming weeks and months, but today instead of words we offer images.

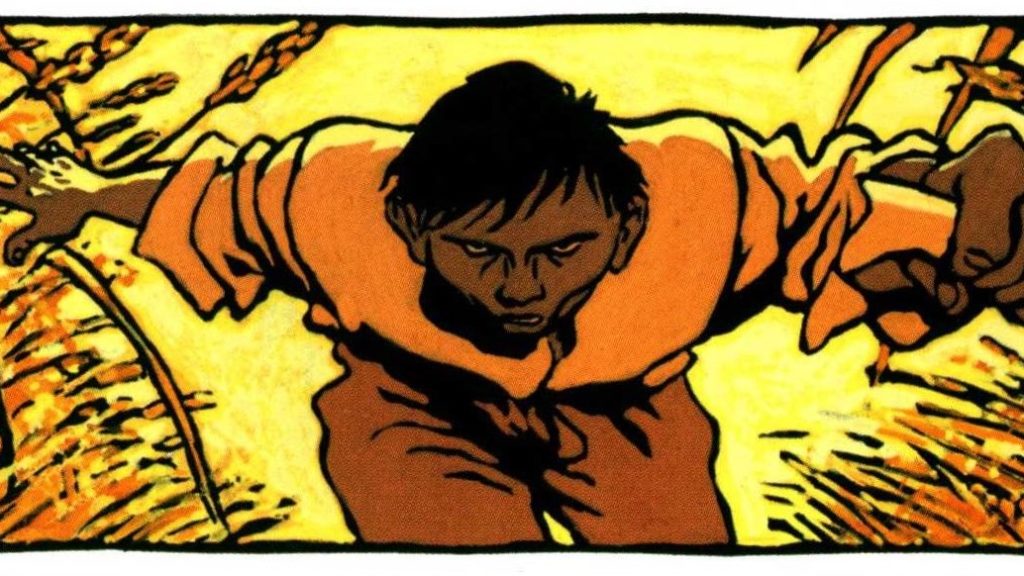

A Golem in Argentina

When an indigenous Argentine woman falls in love with a golem, her grandmother creates a love potion to win the golem’s (perhaps non-existent?) heart. What could possibly go wrong?

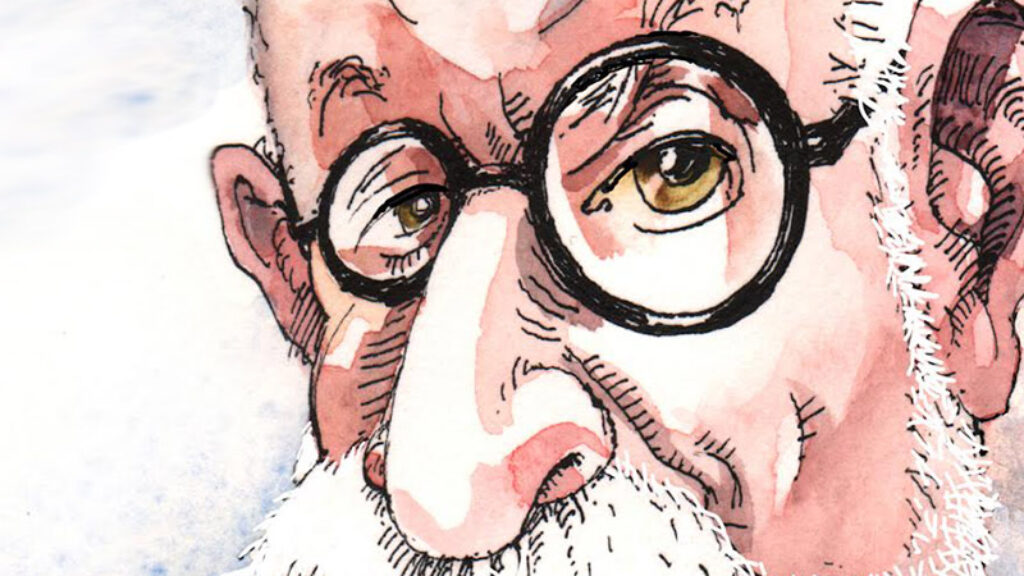

Freud as Talmudist

We now understand Sigmund Freud as an anxious Jewish humanist, not the intrepid scientific investigator he thought himself to be. Does that help explain why his interpretations seem so talmudic?

Starving for Zion

For Chaim Gans, the justification for nationalism in general, and Zionism in particular, lies in the human rights of the individual.

Meshulam Gotlieb

Thanks for this review. I watched the film yesterday and was quite impressed. Schoffman notes that the question of why the true believers suffer the most goes unanswered. Here is the dialogue from the film: “’This is the heart of the matter, that which is most holy suffers the greatest destruction.’ … If you truly believe in God, you have chosen to defend good against evil. The forces of evil are strong. The battle between evil and good is never ending. Those who are at the front of the battle suffer the greatest casualties. It is a choice we have to make it. It is not decided for us… Who cares what choice we make? God cares. If we tolerate evil we are forsaking God and the seed of our own destruction lies in this toleration.... No matter what happens, never be defeated in the chambers of your heart." This sounds like an answer to me.

Marcia Zalev

I am the same age as the reviewer. My older sisters and I have never forgotten seeing this film. I think it was a special showing, because my whole family went to an evening show, which my parents would not normally have chosen for me, where the whole audience was Jewish, united in our love for Israel. What I really remember are the opening and closing shots, knowing from the start that everyone was going to die, and feeling heartbroken as I watched how it came about.

Going to watch it again today on YouTube. Thank you so much for this review and reminder.

ken sutak

Schoffman's analysis of Hill 24 Doesn't Answer is the finest and most perceptive review of this structurally complex film I have ever read. From what I could tell it includes only one (minor) factual error: Hill 24 was the second, not the first, Israeli feature dramatic film to receive international distribution, having been preceded by Faithful City, another film set during the War of Independence (released by RKO in the U.S. on April 7, 1952; Hill 24 was released by Continental in the U.S. on November 2, 1955). Also, although Schoffman's detailed review alludes several times to the many flashbacks utilized by the screenplay, because the film begins the way it does--showing the audience that all four protagonists have been killed in action on that hilltop--this film is a rare example of the use of a triple flashback technique.

David S Levine

One can, if one wishes, watch Hill 24 on YOUTUBE.