Storytelling, or: Yiddish in America

Television writers have a concept called “Flanderization,” which ought to make any writer shudder in horror. The term comes from the character Ned Flanders in The Simpsons. At first, Flanders was a conventional churchgoing neighbor, the straight-man foil for the title family’s chaos. But over many seasons, he devolved into a fundamentalist Bible-thumper—a hyperexaggerated, one-dimensional stereotype of the original figure. This is what happens when writers get successful and lazy, playing to the crowd and letting even their fictional characters deteriorate into pathetic versions of themselves.

Something similar often befalls literary writers whose works achieve popular success, especially when that success transcends language and culture. Such writers respond to a broad audience demanding more of the same by producing not merely more of the same (already a creative loss) but unintentionally exaggerated versions of the same. The cartoonist Grant Snider once illustrated this problem with a “Haruki Murakami Bingo Card”—each square contains one of the powerhouse Japanese writer’s go-to tropes (e.g., “mysterious woman,” “historical flashback,” “precocious teenager,” “urban ennui”).

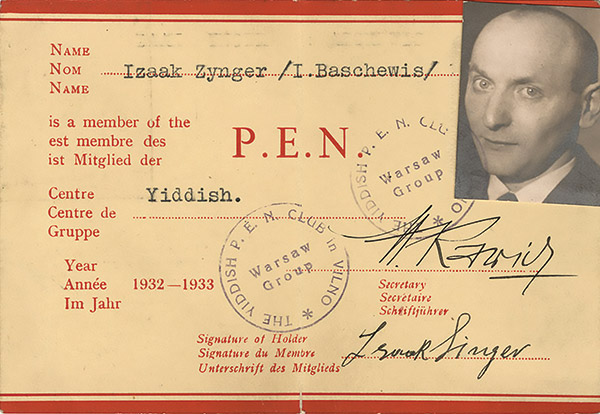

It was just such Flanderization, for lack of a better term, that initially turned me off from the work of Isaac Bashevis Singer, undoubtedly the best-known and most popular Yiddish writer of the twentieth century—especially if we’re counting the second half of that century, and especially if we’re counting non-Yiddish readers. I first encountered Singer through his novels, starting with his magnificent first novel Satan in Goray, which he published while still in Poland in 1935—a surreal seventeenth-century story rooted in the Khmelnitsky massacres and the false messiah Shabbtai Zevi, which also contained a barely veiled commentary on the seductive draw of twentieth-century ideologies.

Entranced, I moved on to the novels he published after immigrating to the United States. The basic recipe for these books called for a guy with at least two wives or lovers from different social classes; the protagonist ping-pongs between them for a couple of hundred pages and then runs away. The novelty and insight of this setup, along with its attendant tensions between religious duty and individual desire, seemed to me to degenerate into self-parody. The Nobel laureate appeared to be phoning it in. His short stories were better, often dramatically so, but still frequently fell into self-derivative patterns in which the recipe involved combining shtetls, demons, and sex in a small bowl, mixed well. Turned off, I turned away.

This was an awkward thing for an American Yiddish scholar to do, because Singer is the only Yiddish writer most English-language readers have ever heard of. That fact is entirely to Singer’s credit—not because of his talent for writing, which he obviously had in spades, but because of his talent for marketing his work to an English-language audience. He cannily adapted his Yiddish work for his new audience, sometimes changing it radically, carefully cultivated (and sometimes romanced) a bevy of translators whose work he often rewrote, and, particularly after his Nobel Prize, constructed a public persona as a wide-eyed innocent from a lost world, which had seemingly left him as its sole surviving spokesman. In public appearances, Singer appeared to play to the non-Yiddish-speaking crowd, giving English lectures full of bromides about the old country and the magic of stories. (The chasm between Singer’s fame and the obscurity of other Yiddish writers of his time, who did in fact exist, was wickedly parodied in Cynthia Ozick’s 1969 story, “Envy: Or, Yiddish in America.”)

Something felt too easy about it all, especially when one compared him with his Yiddish literary contemporaries like Abraham Sutzkever. Sutzkever was a magnificent poet and a cultural hero of the Vilna Ghetto who devoted his postwar career to almost single-handedly preserving Yiddish literature in Israel. His work in every genre felt to me like the opposite of Singer’s—linguistically dazzling, narratively inventive, emotionally raw, intellectually devastating, and burning with an incandescent individuality that made broad strokes or repeats of any kind impossible. In comparison, it was hard not to feel like much of Singer’s work was Yiddish Lit Lite. His affected impish persona imposed a kind of infantilized perspective even when he was writing about ostensibly adult topics like sex, and the lost-shtetl settings of most of his work felt less like an intellectual investment in a meaningful past than an avoidance of reality to please his otherwise assimilated American Jewish readers. In important ways, Singer had turned himself into an English-language writer, and in the process, turned his work and his persona into a kind of Yiddish stereotype. From my ungenerous but not entirely unfair perspective, he’d Flanderized himself.

Over the years, I managed to get past my problem with Singer, mostly by focusing on some of his finest works: his first novel and also a curated handful of his stories, including his debut in English, “Gimpel the Fool” (translated by Saul Bellow), and his 1960s story “The Cafeteria,” each of which deals brilliantly with the question of how one processes or even accepts reality in the presence of radical evil. This, I think, was Singer’s great theme. In a correlation less obvious to his non-Yiddish audience, his literary fascination with doubt and evil was directly related to his rejection of both humanism and Communism. To Singer, they were related ideologies, the benign and malign ends of a spectrum of idolatry that worshiped selfish and limited humanity as though it were the ineffable divine, and thereby both gave rise to the radical evil that made it possible to erase human differences. This is an important argument but a tough sell to those whose nostalgic attachment to their parents’ Yiddish was bound up with an adamantly secular and sometimes fellow-traveling branch of Yiddish-speaking culture. The greatest achievement of Old Truths and New Clichés, a new collection of Singer’s essays compiled by the writer, scholar, and translator David Stromberg, is that it lays bare Singer’s motivating ideas for all to see.

Stromberg’s work here really is heroic. As he explains in the book’s foreword and afterword, Singer was prolific in a manner inconvenient for future scholars, occasionally producing discrete books but more often emitting a continuous flow of prose. This material appeared not only in the Yiddish Daily Forward newspaper, where he published under multiple pen names, but also in his frequent English-language public lectures and in his constant reworkings of translations. His production was relentless, and, overwhelmed as he was, Singer rarely revisited this ongoing effluvia. Stromberg describes how this material piled up in Singer’s “chaos room”:

The walk-in closet where he kept manuscripts, clippings, notebooks, certificates, diplomas, awards, letters, and many other documents and objects connected with his literary and personal life. . . . His son recalls, during the last visit when his mind was clear, Singer going into the chaos room and saying “Oh, my God, I’ve got to live another hundred years to edit the stories, translate them into English, and publish them”—and he did produce enough material to translate, edit, and publish books for several more decades.

Singer famously said that “writers don’t write for the drawer,” and he certainly didn’t, but in leaving a room-sized drawer behind him, he left ample opportunities for people like Stromberg to muck out the stables.

This is hard work, not only because of the chaos room (now more organized at the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas) but because Singer’s nonfiction output is not easily separated into distinct essays. In this collection, Stromberg often merges Singer’s multiple versions of an article or lecture to create a coherent finished product. The book’s ample notes treat all this with a reverence usually reserved for biblical manuscripts, delineating each passage’s textual variants and also revealing the effort required to determine even the most basic information about the material included (“This poem, handwritten in the original English, is undated, though it appears on the back of a letter sent by the Carl Hanser Verlag, dated August 13, 1980”). Stromberg’s notes also disclose how many pieces in this collection—9 out of 19—are actually Singer’s English works, marked with the note “No Yiddish original has been found.” It must be said that the strongest essays in the book are these English ones.

The great accomplishment of this collection is to extract Singer from his own schlock and reveal him as a true intellectual with a coherent artistic vision. In Singer’s Yiddish voice, Stromberg explains:

All traces of sentimentality and schtick fall away. In Yiddish, Singer doesn’t have a Yiddish accent. He doesn’t sound like your grandfather—or your great-grandfather—as he did when he arrived from Poland. He sounds like a writer whose mind is constantly working and whose vision reaches beyond everyday illusions to what drives our human nature, no less than to what lifts our human spirit. . . . His commercial success coincided with his shedding of the intellectual aspect of his public persona, and his cultivation of a new image, that of a translated old-world transplant. In reality, he was a modern writer.

One feels for Stromberg as he pleads this case—because one senses, in its profound unspoken sorrow and the desperate clinging to Singer’s back-of-the-envelope scribblings, the realities beneath it. The fact that this case for an artistic vision needs to be made at all—for a Nobel laureate!—is itself a product of the many decades of subtly internalized antisemitism that gradually eroded Singer’s Yiddish-language audience in the United States, combined with the entirely unsubtle antisemitism that destroyed Singer’s audience in Europe. Why, one might ask, did Singer cannily realize that becoming a cartoon version of himself was what the masses wanted? Might it have to do with the fact that several generations of American Jews, having deeply internalized their own social rejection by the antisemitic atmosphere of the mid-twentieth century United States, regarded Yiddish as the language of, to use the broadest term, losers?

Yiddish literature of the twentieth century contained a phenomenal intellectual discourse, and there is a clear reason why twentieth-century English-speaking American Jews had no interest in exploring that discourse. They’d worked hard to not be losers. Especially after the Holocaust, it was a lot safer and more comfortable for them to believe that the Yiddish-speaking world they’d abandoned consisted of sad sacks whom they could look back upon with condescending nostalgia, rather than people who were, at the very least, their intellectual equals. Singer was always more of a storyteller than a thinker, but if he chose to deemphasize the intellectual elements of his work once he arrived in the United States, it wasn’t because he was stupid. It was because he was smart enough to know what his audience wanted.

Which brings us to the challenge Stromberg raises: If we don’t know the real Singer, who is the real Singer?

If this collection’s goal is to present Singer as an intellectual powerhouse, it must be said that Singer’s ideas, as expressed in these essays, are unlikely to dazzle—though that is mostly because of his own success in driving these ideas into American Jewish discourse. One essay, for instance, explores the attraction of Kabbalah. While Singer’s exposition of Jewish mysticism is entirely accurate, it’s written from a popular point of view that emphasizes self-discovery: “The picture that I have painted of the Kabbalah expresses not only what I have learned, but also what I am myself, my personality, my ideas, and my work. Such is the Kabbalah, that every soul sees in it a personal light.” This must have felt fresh fifty years ago, but by now Kabbalah has been “discovered” to the point of parody, and the self-actualization Singer celebrates has likewise been so overdone that one inevitably reads this entirely intelligent essay through the filter of its Flanderized spawn, like reading Jane Austen through the lens of Carrie Bradshaw and Bridget Jones.

Likewise, an essay titled “Why Literary Censorship is Harmful” surely felt like a bold statement when Singer’s writing about sex was scandalous; it’s a testament to the success of Singer (among many, many others) that today it reads like a tenth-grade homework assignment. In many essays here, Singer similarly rants about “psychology” and “journalism” passing themselves off as literature. He won that battle too; the postwar Truman Capote–induced craze for nonfiction novels is long gone, and Singer’s own stock today is surely worth more than, say, Norman Mailer’s. So, if these old truths now feel like new cliches, what remains here for readers?

Fortunately, plenty. Singer did have an artistic vision that reaches beyond the bogeymen of his era. That vision is of storytelling as the necessary foundation for creative art, and even more than that, the foundation for living a life of openness and purpose. His best polemical work here comes when he lays out this idea from his own experiences as a writer, as he does in “Storytelling and Literature” (“No Yiddish original has been found for this essay,” Stromberg notes). Singer predictably complains about how contemporary writers promote their politics instead of telling stories, but he also unearths the real structural problem with this approach: “You cannot sit down at your desk and write a novel to enhance socialism, Zionism, communism, liberalism, or any other ism. . . . Literature is storytelling—and you cannot tell a story about the future.” And then he digs deeper:

All talented people—no matter what kind of education they have been given, no matter what their background—all somehow think and brood about the so-called eternal questions. . . . People who never ask themselves these questions, people who make peace with them, think that their lives are as they are, that people are as they are, and that everything that happens to us is history. Since we cannot help it, let’s ignore it. But real artists cannot ignore it. They keep on asking themselves the eternal questions.

Real art, Singer argues here, is driven by the relentless pursuit of such questions without the expectation of answers. This is the reason why agenda-driven art must fail: it starts with the answers.

Singer is right about this, which is why his essays are in a sense doomed to failure too, or at least doomed to pale in comparison with his fiction. I hate to say it, but the essays that make this collection worth reading—and it is absolutely, beautifully worth reading—are the ones in which Singer stops making arguments and goes back to his greatest talent, which is, yes, storytelling. One wonderful piece contained here is “Love and Magic, Or, A Trip to the Circus” (“No Yiddish original has been found,” Stromberg notes again), a memoir of the author sneaking away from his religious home in Warsaw to visit a circus with the girl of his dreams. In other hands, or even at another time, this piece might have been predictable boilerplate about the limitations of religion and the wonders of childhood. Here, though, it becomes a beautiful meditation on how one finds and relocates that wonder in one’s life even after foundation after foundation of belief has been destroyed.

Something similar happens in the book’s penultimate essay, “The Making of a First Book,” which begins unpromisingly with an overly generalized history of Jewish messianic movements but then becomes a story about the author’s enchantment with how Judaism incorporates the past into the present:

I was brought up in a house which, I might say, was a reliving of Jewish history in a miniature way. The Bible, the Mishnah, the Talmud, the Zohar, and all the Jewish movements were as real in our house as if they happened on Krochmalna Street. . . . Hundreds and even thousands of years seemed as near to us as yesterday. I was seriously in love with Mother Rachel even before I fell in love with our neighbor’s daughter Shosha.

Decades later, the historian Yosef Yerushalmi would articulate this Jewish understanding of time in his famous book Zakhor: “What was suddenly drawn up from the past was not a series of facts to be contemplated at a distance, but a series of situations into which one could somehow be existentially drawn.” Singer said it better.

The book’s best essay, a showstopper, is “Why I Write as I Do.” (Yet again, “No Yiddish original has been found.”) Despite its title, it isn’t a polemic but a memoir. Its story will be old news to Yiddish readers who know the outlines of Singer’s life, but for most English readers, this drama and what Singer drew from it will be revelatory. Even for those familiar with the facts, Singer’s version of his origin story is worthy of attention, because his life was itself a kind of “reliving of Jewish history in a miniature way.”

Raised by deeply religious parents, but with two older siblings who were both writers and both in thrall to the antireligious pull toward rationalism (Singer focuses here on his brother, the novelist Israel Joshua Singer, rather than his sister, the novelist Esther Kreitman), Singer himself experienced the whiplash that twentieth-century Jews endured when the supposedly rational non-Jewish world they’d dreamed of entering turned out to be the least rational and most horrific society of all. Like many twentieth-century Jews, Singer reacted to this betrayal by forging a new kind of identity for himself—in his case, not exactly a return to religious life but a deep loyalty to the old truths of Jewish identity and the realization that it was not optional and never was. “I did not conceive of this as a philosophy for others, but strictly for myself,” Singer writes, as he explains his belief in God as a deep attunement to divine creativity: “Yes, God is a writer.”

I was prepared to be annoyed by this rather self-congratulatory version of religious belief. As I read, I feared that Flanderization was afoot, and this time not merely of a writer but of Jewish tradition itself. But Singer swept me along with his illumination of art’s connection to suffering, creation’s connection to freedom, and his praise for God as a “struggling artist.” And then he told me how the stars turned into the letters of the alphabet, and I forgave him for everything.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Poet from Vilna

Avrom Sutzkever and Max Weinreich, a memoir.

Cynthia Ozick: Or, Immortality

Ozick is as marvelously demanding, harrumphing, and uncompromising as she has always been.

A Harem of Translators

Singer insisted that all foreign-language translations of his work be based on the English versions. And most of them were done by young women who closer to typist-editors than true translators.

My Scandalous Rejection of Unorthodox

All of us in the online OTD community have gone through some version of the transformation Unorthodox dramatizes, and we gobble down and fiercely debate every new OTD memoir that hits the shelves, every documentary and movie that comes out.

Iris

The killer phrasing in this piece is "...Singer himself experienced the whiplash that twentieth-century Jews endured when the supposedly rational non-Jewish world they’d dreamed of entering turned out to be the least rational and most horrific society of all."

The description of Singer essentially working himself out of a job because his positions became mainstream is fascinating. And it would be amusing to refer to his "chaos room" as a geniza.