Lion of Judah

In 2004, a Hasidic man with a long black beard came onto Jimmy Kimmel Live! to sing about praising God in a semi-Jamaican accent. Even now, it’s astonishing to watch Matisyahu—bespectacled, black-hatted, and confident—perform his set on late-night television. His reggae beatboxing, dm-da-da-btt-te-taa-tikt, quickly shifts into the yibbio-bo-bums of a Hasidic niggun before he sings, “No matter where I am, bless me with all your light. . . . Let me stop praise your name. . . . Bob Nesta [Marley] said it best, everything will be alright.”

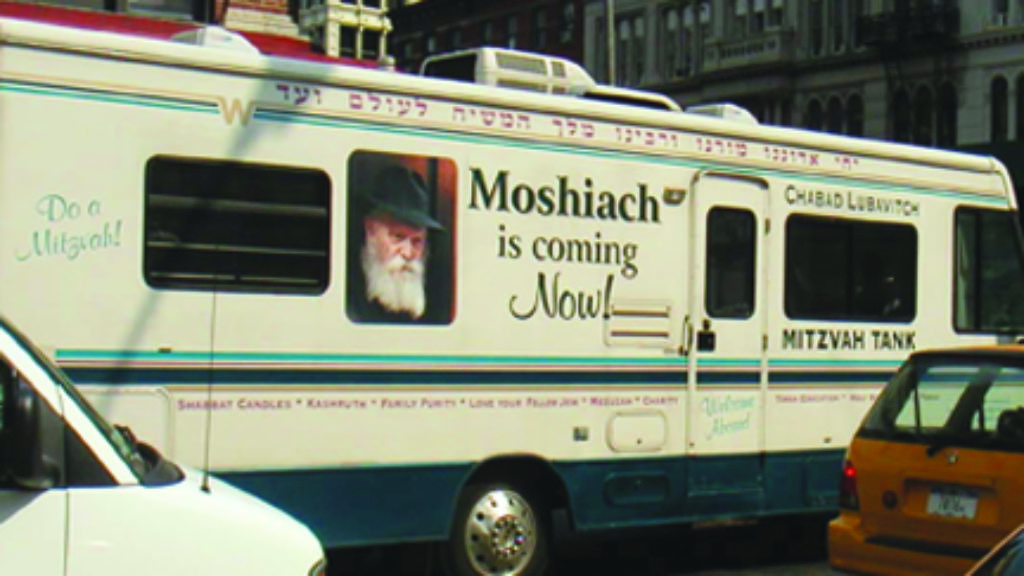

In two minutes, Matisyahu introduced himself to the world and rocked the house, as a bewildered Jimmy Kimmel said when the singer walked over to the couch to chat after playing “Close My Eyes.” Kimmel and his other guests (sitcom star Scott Baio and comedian Kevin Nealon) didn’t know where to begin. “How did you become this rapper?” Kimmel asked, laughing. Softspoken, Matisyahu told him, “The Lubavitcher Rebbe was saying you should go out into the world and turn the world over and . . . help people to connect to godliness.” Kimmel followed up by asking if Matisyahu cursed (no) or did drugs (no) and how much money it would take to have him perform on Shabbat. The answer, then, was that no amount was worth it.

Matisyahu might have seemed like a novelty act to Kimmel and friends, but Shake Off the Dust . . . Arise, the debut album he recorded while studying in a Chabad yeshiva, hit number four on the US charts and number one on the reggae charts. For a while, Matisyahu was American Judaism’s biggest star, with four albums in the top forty and global tours that brought him and his beard to Israel, Spain, Norway, Australia, and Japan. Twenty years after the release of his astonishing first album, Matisyahu, though in a very different incarnation, is still rocking.

Matisyahu was born Matthew Miller in 1979 to a loosely affiliated Jewish family in White Plains, New York, where he was an indifferent student, played sports, listened to Bob Marley, and “started smoking pot and having sex” at age fourteen. When he was sixteen his parents sent him to an Israeli high school program for Americans, but when he talks about his teen years, he remembers following the band Phish on tour and spending time in an Oregon rehab center. Ironically, it was Bob Marley singing things like “the Lion of Judah shall break every chain” that led him to his first real interest in Judaism. Of course, for Marley, Rastafarians like himself were the true descendants of ancient Israelites (and the Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie, who had been assassinated in 1975, was their messiah).

Matthew didn’t become Matisyahu until after he moved back to New York. He started taking classes at the New School and hanging out with two downtown Chabad rabbis. Like many young Jewish searchers, Matisyahu dove headfirst into Lubavitch Hasidism in those heady years after the Rebbe’s death, when many of his followers expected his imminent messianic return. He also attended the Carlebach Shul on Manhattan’s Upper West Side and counts the folk-singing Shlomo Carlebach (who, like the Rebbe, also died in 1994) as a key influence.

At first, Matisyahu buried his musical interests beneath Chabad, even adopting a Crown Heights, Brooklyn, accent—though a few grainy videos show him rocking out in shul basements, rapping in front of sparse crowds beneath fluorescent lights. In “King Without a Crown,” his first hit, Matisyahu sings, “Strip away the layers and reveal your soul / Got to give yourself up and then you become whole.” In interviews over the last few years, he has described his transformation somewhat differently. He says that he made a sort of bargain with God—he would do the whole Chabad thing in exchange for musical success, which is what he always wanted. However he got there, Matisyahu’s performances as a young artist were electric. He would work up a sweat in minutes as he hopped, twirled, and even high kicked his way around the stage. His dancing on videos of these performances is actually terrible, which somehow makes it endearing—he frequently kept a hand on his head to prevent his large velvet kippa from flying into the crowd.

The question swirling around Matisyahu’s career from the beginning was just how seriously to take him. In some ways that’s still the question, but his debut album was no gimmick. It was a thoughtful, winding yet cohesive work of self-reflection, dense with cryptic allusions. In the lead song, “Chop ’Em Down,” Matisyahu sings, almost in passing, “Six hundred thousand witnessed it, no you didn’t forget,” without explaining that he’s referring to the revelation at Sinai, the six hundred thousand Israelites who, according to tradition, were at the foot of the mountain, or the idea that all Jewish souls carry the memory. Throughout the album, Matisyahu sings about bondage in Egypt and guidance from heaven (Mitzrayim/Shamayim, a handy rhyme), occasionally breaking into wordless Hasidic niggunim. In the song “Got No Water,” he suddenly cries out, “sh’yibane Beis Hamikdash bimheira bi-yameinu,” imploring God to rebuild the holy temple speedily in our days.

Chabad fervor turned out to be a potent source of inspiration. In the same song, Matisyahu sings, “If you got no water how you gonna survive. . . . Chabad philosophy that’s the deepest well-spring.” The second song on Shake Off the Dust . . . Arise, “Tzama L’chol Nafshi (Psalm 63:2–3)” (my soul thirsts for you), was a favorite of the Lubavitcher Rebbe. In “Close My Eyes,” he sings, “The Rebbe said it best, Moshiach’s coming tonight.” The multilayered song “Aish Tamid” vividly paints the picture of a destroyed Jerusalem, a decaying New York City, and a man trying to rebuild himself and his world. Matisyahu croons the refrain, “Wondering where you’ve been, won’t you / Won’t you come on home to me?” In several songs he shouts, “We want Moshiach now!” which was not surprising for newly minted Lubavitch ba’al teshuvah but was—and remains—astonishing for a pop star on the rise.

Shake Off the Dust . . . Arise was well received by critics, but it was Matisyahu’s 2006 second studio album, Youth, that sold over half a million copies, earned him a Grammy nomination, and made him the world’s only Hasidic reggae superstar. Although still steeped in Jewish references—the lead track, “Fire of Heaven/Altar of Earth,” opens with a talmudic (and maybe playfully Rastafarian) reference to holy fire in the shape of a lion—the album is shorter and less meandering than his first. There are no niggunim or psalms, and some songs, like “King Without a Crown,” are rerecorded at a faster, less reggae tempo. My personal favorite of Matisyahu’s work comes from this album—“Dispatch the Troops,” a mournful retelling of Lamentations that switches between first and third person in a dialogue between God and the Jewish people, here rendered as the “Daughter of Zion, once precious princess” who “left her father’s house to walk streets that never rest.” They have, to say the least, a complicated relationship: “Won’t you please return child, where ya been? / She says, ‘I can’t come home cause he won’t let me in, and besides we don’t need no more friction.”

I was in elementary Jewish day school in Matisyahu’s early years, and the kids who had flip phones set the songs as their ringtones. Throughout the Jewish world, bad rapping and cringeworthy reggae accents abounded. We loved Matisyahu—not just for his music but for who he was—and spoke about how he wouldn’t perform on Shabbat in awed voices. We traded stories of the times we (or people we knew, or people who told people we knew) saw him at shul. He played in New York frequently to packed houses full of young Orthodox Jews staring at him enraptured and older Jews quizzically wondering why this hyperkinetic Hasid was shouting at them. But even the skeptics recognized that he was really out there in the wide world, making music that was actually popular and distinctively Jewish without being kitschy or off tune. Sometimes at his best—like Dylan or Leonard Cohen but more Jewish—he sounded like he had been plucked from the prophets of old.

He had his detractors, of course. A friend’s high school rabbi insisted that Matisyahu’s music was not Jewish and forbade listening to it. Some members of Chabad chafed at his use of Lubavitch dress and themes, accusing him, as one writer put it, of wearing “Hasidface” (the movement itself was happy to put him on the telethon; after all, he was the most famous living Lubavitcher). Other critics placed him in a long line of Jewish musical appropriation stretching back to Al Jolson’s blackface in The Jazz Singer. But to be fair, Matisyahu’s religious fervor was palpably genuine, and he was neither the first nor the last white guy to perform reggae (a few years ago, he toured with UB40, the stars of “white boy reggae” in the 1980s and 90s). And, needless to say, he couldn’t be accused of appropriating the Israelite experience or celebration of the “Lion of Judah.”

Over the next few years of endless touring, Matisyahu slowly abandoned the button-downs, suits, and visible tzitzit for more casual outfits of a rockstar. He also released his third album, Light, which received middling reviews but includes his biggest hit—“One Day”—which was played incessantly as an anthem for global peace by NBC during the 2010 Winter Olympics. Despite the song’s gentle messianism (“All my life I’ve been waiting for, I’ve been praying for, for the people to say / That we don’t want to fight no more”), it was completely remade by a studio production team that included Bruno Mars. Matisyahu likes to say that the only part of the song he wrote was the phrase “blood-drenched pavements,” but maybe he also wrote the line “Under the same sun, singin’ songs of freedom,” a nod to Bob Marley’s “Won’t you help me sing / these songs of freedom?” from “Redemption Song.”

Matisyahu debuted the most infamous Jewish haircut since Samson when on December 13, 2011, he posted a picture of himself clean-shaven. The story was picked up by everybody from the Jewish Telegraph Agency to Rolling Stone, not to mention the bloggers.ABC News ran a story about the shaving of his “trademark” and “iconic” beard as searches for Matisyahu spiked on Google.

One Jewish journalist wrote that “we were all in mourning” when Matisyahu shaved his beard, and that was no exaggeration. I remember being deeply confused by the photo. One of my teachers said, “This is what happens when you hang around with the kind of people in music.” After the photo, Matisyahu posted a brief explainer to his website:

Sorry folks, all you get is me . . . no alias. When I started becoming religious 10 years ago it was a very natural and organic process. It was my choice. My journey to discover my roots and explore Jewish spirituality—not through books but through real life. At a certain point I felt the need to submit to a higher level of religiosity . . . to move away from my intuition and to accept an ultimate truth. I felt that in order to become a good person I needed rules—lots of them—or else I would somehow fall apart. I am reclaiming myself. Trusting my goodness and my divine mission.

He was “stripping away the layers” again to reveal his soul, but now he refused to “give himself up” to tradition or Hasidism with its many, many rules. He also went back to drug use, or at least marijuana, after repeatedly criticizing it in his early lyrics. Nowadays, he always has a blunt in hand when he is interviewed.

Whether it’s his return to drug use, or because he reneged on his deal with God, or, like Samson, sheared off the source of his power (or at least the identity that tied him to his most devoted fans), Matisyahu’s stock has sunk over the last decade. Unlike some Jewish artists, his religious estrangement hasn’t been inspiring. His albums since then have received less notice and have had less urgency to them. It has made him defensive: “Got it on the inside I don’t need to wear it out / Can’t say I’m not religious I just let go of the doubt.” It’s fair to note that Matisyahu nowadays does say he’s not religious. On his 2014 album Akeda, he entertainingly lists the flaws of Judaism’s forefathers (and mothers), only to conclude, somewhat lamely and defensively, “Nobody’s perfect, hope you can relate.”

There have been plenty of bad songs in these years. In “Tel Aviv’n,” his once-spiritual and poetic love for an Israel blessed by God is replaced with jingoistic lines about cool Israeli guns. Most cringey of the flops was “Happy Hanukkah,” in which Matisyahu bombastically sings, “Happy Hanukkah! I wanna give a gift to you,” and reminds the listener that “today is the day, tonight is the night.” The accompanying music video was made with all the green-screen verve of a teenager using iMovie in 1999. It’s an outlier, true, but also an indication that sometime after he shaved his beard and reclaimed himself, he also stopped trying too hard to be good.

If there is one area in which Matisyahu has found recent attention, it’s in his pro-Israel stance. He’s loved Israel since he was a teenager and has spoken out repeatedly against the BDS movement. After October 7, he was fiercely vocal in defending Israel and faced canceled shows for it in Spain; Tucson, Arizona; and, most recently, Chicago, after threats from anti-Israel activists. Last November, he released the track “Ascent” in response. It’s both the most urgent, animated track he’s released in a long time—he sounds angry and impassioned—and still sort of goofy. When fighting antisemites, he’s so strong he’s “got room to take naps and come back.”

Matisyahu’s days of stardom are behind him, but that was inevitable, given the nature of pop culture. Unfortunately, his artistic inspiration seems to have largely gone too. I don’t begrudge his religious transformation, but Chabad theology and the Bible were the wells he drew from for his best songs, and if there is an angry or melancholy song about how those wells are now closed to him, in the vein of modern Jewish artists from the maskilim and Yiddish poets to Yehuda Amichai, he has yet to sing it. Perhaps that’s because he’s not really angry. He’s even still fond of Hasidism. His first postbeard album, Spark Seeker, was inspired by the kabbalistic idea that sparks of holiness hide within each person waiting to be brought out. And just this past July, he posted a speech from the Lubavitcher Rebbe on Instagram, writing, “The Rebbe’s words always ringing with truth. Never got to meet you but have always felt you to be the one who gave me the ability to break down my biggest wall and rise to meet my purpose.”

In August, I went to a Matisyahu concert at a little Connecticut winery. There were about three hundred people in attendance, but it was hard to tell who was there for the old reggae star and who for the wine and cool air. A lone fan shouted, “We want Moshiach now!” throughout the concert, and most of the smoking came from the stage.

The Matisyahu on offer that night was shaved bald, with just a bit of a scruffy beard, much like the man in the 2012 photo. He opened with “Close My Eyes,” but twenty years after his debut on Kimmel, there was no beatboxing and no niggun to warm up the audience. Still, the crowd loved him.

Maybe Matisyahu’s best days were twenty years ago, when he strutted around Crown Heights and onto Jimmy Kimmel’s set in his beard and hat, but early in the evening, a familiar guitar lick rolled in, and Matisyahu sang “King Without a Crown,” sending up the loudest cheers of the night. Cradling the mic, he sang, “I believe, yes I believe I said I believe,” and I danced with the swaying crowd.

Suggested Reading

Wild Things: The New Neo-Hasidism and Modern Orthodoxy

Who are Joey Rosenfeld and his pseudo-Hasidic pranksters, and what does their success have to do with the future of Modern Orthodoxy?

American Gods

One need not buy into the cultural importance of “Snapewives” to accept that the digital age is one in which individuals demand narratives, practices, and communities they find personally meaningful.

The Chabad Paradox

Despite its tiny numbers, the Hasidic group known as Chabad or Lubavitch has transformed the Jewish world. Not only the most successful contemporary Hasidic sect, it might be the most successful Jewish religious movement of the second half of the twentieth century. But two new books raise provocative questions about it.

A Cipher and His Songs

Avraham Halfi faced outward, a gifted comic performer, and inward, a lyric poet of resonant privacy.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In